“Who Will Write a Story for the Children of Eric Garner?”

AALBC Guest Post by Zetta Elliott

“Who will write a story for the children of Eric Garner?”

This question came to mind last February when I was invited to prepare a ten-minute talk for the PBS program Blackademics TV. Today, as I rage over the non-indictment of yet another murderous white police officer, I might ask, “Who will write a story for the sister of Tamir Rice?”

The Blackademics series, which aired in Austin, TX this past November, asks African American scholars to present their research in a way that’s meaningful and accessible to the general public. I’d seen the power of various TED talks and at the urging of a friend, submitted a proposal that would allow me to share my research on racial disparities in US children’s literature. I’ve written countless essays on the subject, but hoped a televised talk might circulate in a way that would prompt a national conversation.

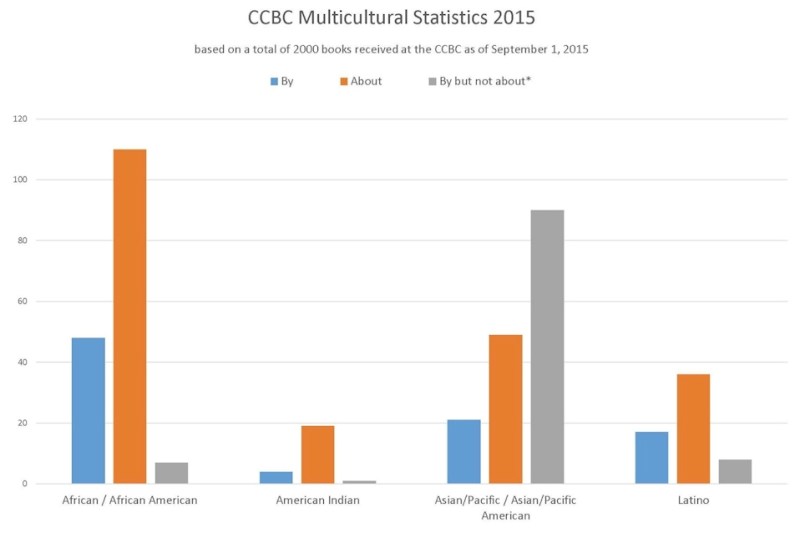

When our kids are being shot dead in the street, it can be hard to think of children’s literature as a priority. So many other issues need the attention of our community: police brutality, the school-to-prison pipeline, gun violence, child poverty. But in my Blackademics talk I argue that the consequences of “symbolic annihilation” can be just as dire. What happens to children who never see themselves reflected in the pages of a book—or only see themselves represented as “happy slaves?” Statistics compiled annually by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC) show that very few books published in the US serve as “mirrors” for children of color despite the fact that they now represent the majority of school-age children (Tina Kugler’s illustration makes this abundantly clear). In 2014 the number of books about African Americans spiked, but most of those books were not written by Black authors (this trend continued in 2015). According to a Publishers Weekly survey only 1% of publishing professionals self-identify as African American, so these numbers are hardly surprising.

But what effect do they have on our kids? Think of the doll test developed by psychologists Mamie and Kenneth Clark in the 1940s. Eventually used in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case, the Drs. Clark intended the experiment to prove “the influence of race and color and status on the self-esteem of children.” In 2005, teen filmmaker Kiri Davis recreated the doll test in her short film A Girl Like Me. It’s heartbreaking to watch Black children reaching without hesitation for the white doll when asked, “Which is the nice doll?” and then faltering when asked to point out the doll that looks like them (“the bad doll”). What would happen if we conducted a similar test with books instead of dolls—would the results be the same?

African American children receive countless messages even in infancy that contribute to feelings of inferiority and/or invisibility. For example, when you never see yourself depicted as the hero, you learn that heroic qualities belong only to others. After Earth was a flawed film and didn’t enjoy commercial success, but to me it’s invaluable for its representation of a Black boy drawing upon the wisdom of his father to survive in a hostile environment and ultimately to vanquish the alien.

We now have John Boyega as Finn in Star Wars: The Force Awakens, but most kids in the US can probably count on one hand the number of action films they’ve seen that feature an African American youth as the hero (as opposed to a secondary character who exists only to sacrifice herself for the white hero—think Rue in The Hunger Games). The number of sci-fi or fantasy films that show Black girls in the lead role are even harder to find, though the books do exist (see my list). This matters because, as I argue in my Blackademics talk, speculative fiction can teach our youth to use magic and/or technology to design an alternate universe—a realm where they are heroic, empowered, and able to demand the justice that remains so elusive in this world.

Several years ago I had the opportunity to meet Angela Davis. Her lifelong activism is inspiring but I was most struck by her description of her childhood, and the ways her parents consciously tried to counter the limitations imposed upon Black children in Jim Crow Alabama. Davis traveled extensively and learned foreign languages because, she explained, her parents were trying to prepare her for a world that didn’t yet exist. Black parents in the US do all they can to prepare their children to survive the many perils that await them. But if we want our youth to thrive, we must feed their imagination with books and other fantastic narratives so that they are able to dream of—and build—the kind world they deserve to call home.

Born in Canada, Zetta Elliott moved to the US in 1994. Her poetry has been published in several anthologies, and her plays have been staged in New York, Chicago, and Cleveland. Her essays have appeared in The Huffington Post, School Library Journal, and Publishers Weekly. She is the author of twenty books for young readers, including the award-winning picture book Bird. Elliott is an advocate for greater diversity and equity in publishing. She currently lives in Brooklyn. Visit her website at: www.zettaelliott.com.

Born in Canada, Zetta Elliott moved to the US in 1994. Her poetry has been published in several anthologies, and her plays have been staged in New York, Chicago, and Cleveland. Her essays have appeared in The Huffington Post, School Library Journal, and Publishers Weekly. She is the author of twenty books for young readers, including the award-winning picture book Bird. Elliott is an advocate for greater diversity and equity in publishing. She currently lives in Brooklyn. Visit her website at: www.zettaelliott.com.

Related Links Provided by AALBC.com

- 100 Important Books for Children

- Ten Steps to Promote Diversity in Children’s Literature

- Best-Selling Children’s Books

- More, Books for Children Whitewash the Horrors of Slavery

- Transcript from Panel Discussion (featuring Wade Hudson): “Where are the People of Color in Children’s Books?”

- “The New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Books of 2015” (failed to select a single book featuring a Black illustrator)