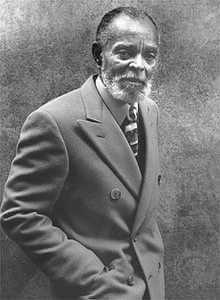

Chester Himes

by Michael Marsh

Published: Friday, December 4, 1998

Long before becoming a famous novelist, Chester Himes was a budding criminal. But his life changed after he was arrested in Chicago.

His approach to his first vocation, like his later writing, was simple and direct. In November 1928, he walked into the house of an elderly couple in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, and fled in their Cadillac with some cash and a fistful of jewelry. The car got stuck in some mud, and he had to walk for hours until he caught a bus heading west. He planned to pawn the jewels at a shop in the Loop owned by “Jew Sam,” whom his hoodlum friends had recommended. Once he arrived at the pawn shop, however, the police were called, and Himes was arrested. At the station, detectives tied his feet together, handcuffed his wrists behind his back, and pistol-whipped him before turning him over to a

His approach to his first vocation, like his later writing, was simple and direct. In November 1928, he walked into the house of an elderly couple in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, and fled in their Cadillac with some cash and a fistful of jewelry. The car got stuck in some mud, and he had to walk for hours until he caught a bus heading west. He planned to pawn the jewels at a shop in the Loop owned by “Jew Sam,” whom his hoodlum friends had recommended. Once he arrived at the pawn shop, however, the police were called, and Himes was arrested. At the station, detectives tied his feet together, handcuffed his wrists behind his back, and pistol-whipped him before turning him over to a

Cleveland Heights detective. He wound up with a 20-year sentence in the Ohio State Penitentiary. During the seven and a half years he served, Himes would write the short stories that launched his literary career.

Yet that career would be marked by hardship as well. Despite having these prison stories published in national magazines, once he was back on the street he had to eke out a living at such jobs as waiter and sewer digger. With the start of World War II, Himes and his first wife, Jean Johnson, moved to Los Angeles, where he worked in two shipyards and also shoveled gravel and sand. In 1945 he completed his first novel, If He Hollers Let Him Go, a story of racism in the workplace, but the book was a commercial failure.

Two years later, frustrated and angry, Himes was called back to Chicago. Horace Cayton, who cowrote the classic sociological work Black Metropolis with St. Clair Drake, had asked Himes to give a talk at the University of Chicago. Fortified by champagne and Benzedrine, Himes provided a key to understanding his agenda as a writer. In a speech entitled "The Dilemma of the Black Negro Novelist in the United States," he argued that black writers have no choice but to present truths that make both whites and blacks uncomfortable: "If this plumbing for the truth reveals within the Negro personality homicidal mania, lust for white women, a pathetic sense of inferiority, paradoxical anti-Semitism, arrogance, Uncle Tomism, hate and fear and self-hate, this then is the effect of oppression on the human personality." After the speech, the mainly white audience sat in stunned silence. Himes stayed in town another week, drinking the whole time.

With little fanfare, Himes was posthumously honored in Chicago this October, when he was inducted into Chicago State University’s National Literary Hall of Fame for Writers of African Descent. He was not as well known or appreciated as most of his fellow honorees-distinguished writers like Gwendolyn Brooks, Toni Morrison, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, and James Baldwin. His popular legacy may rest solely on a series of detective novels, which follow the exploits of a pair of black police detectives in Harlem; that series spawned three movies, including 1970’s Cotton Comes to Harlem. But Himes produced 17 novels, more than 60 short stories, and two autobiographical volumes, revealing a unique knowledge of the dark side of human nature and the corrupting influence of racism. He believed in the basic brutality of man and, especially in his early works, man’s helplessness in the face of circumstances. Life is often a stacked deck. Himes retained this perspective throughout his career, perhaps because it evolved out of his own experience.

The youngest of three sons, Himes was born in Jefferson City, Missouri, in 1909 to parents who were radically different from each other. His father, Joseph, was a dark-skinned male in a racially explosive era. He was a friendly, almost obsequious man who taught mechanical arts at black colleges in the south. Himes’s mother, Estelle, was a housewife who had studied music in a Philadelphia conservatory. She taught Chester and his brother at home for a few years after the family moved to Mississippi, because she felt the elementary schools there were not good enough. A fair-skinned woman, she was fiercely proud of being part white. Himes inherited both her pride and her hatred of racism. In the first volume of his autobiography, The Quality of Hurt, he wrote:

“My father was born and raised in the tradition of the Southern Uncle Tom; that tradition derived from an inherited slave mentality which accepts the premise that white people know best, that blacks should accept what whites offer and be thankful, that blacks should count their blessings. My mother, who looked white and felt that she should have been white, was the complete opposite&heppip; She was a tiny woman who hated all manner of condescension from white people and hated all black people who accepted it.”

The couple’s personality differences created bitter arguments.

When Himes was about 12 years old, his father took a teaching job at Branch Normal College in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and soon a tragedy took place that would profoundly shape Himes’s view of race relations. He had misbehaved-"perhaps said a ’swear word’ in my mother’s presence, or was disobedient, or ’sassed’ her"-and his mother made him sit out a gunpowder demonstration that he and his brother, Joseph Jr., were supposed to conduct during a school assembly. Working alone, Joseph mixed the chemicals; they exploded in his face. Rushed to the nearest hospital, the blinded boy was refused treatment. "That one moment in my life hurt me as much as all the others put together," Himes wrote in The Quality of Hurt.

“I loved my brother. I had never been separated from him and that moment was shocking, shattering, and terrifying… We pulled into the emergency entrance of a white people’s hospital. White clad doctors and attendants appeared. I remember sitting in the back seat with Joe watching the pantomime being enacted in the car’s bright lights. A white man was refusing; my father was pleading. Dejectedly my father turned away; he was crying like a baby. My mother was fumbling in her handbag for a handkerchief; I hoped it was for a pistol."”

Estelle Himes took her injured son to Saint Louis for treatment; Chester and his father followed several months later. But Joseph Himes couldn’t find work, so he moved the family to Cleveland, where his brother and two sisters lived. At 17, Chester graduated from high school and worked as a busboy at the Wade Park Manor hotel to earn money for college. One day, while leaning against a faulty elevator door, he fell down the shaft and broke his left arm, his jaw, and three lower vertebrae. After investigators concluded the hotel was at fault, Wade Park officials offered to continue Himes’s $50-a-month salary in exchange for signing a waiver not to sue. Himes, who was also granted a disability pension from the state of Ohio, followed his father’s advice and signed the waiver. When his mother found out, she angrily confronted the hotel’s management, who then reneged on the deal. His parents argued over the situation-Estelle called her husband "spineless"-and their relationship further deteriorated; they divorced in 1928.

Himes recovered well enough to enroll at Ohio State University in Columbus, but the predominantly white environment "depressed" him. He neglected his studies, failing most of his subjects during his first quarter, and barely avoided expulsion. Then he was kicked out shortly after Christmas break: he had taken several black schoolmates to a whorehouse because he thought they were acting too proper or "white." With no classes to attend, Himes devoted himself to gambling, drinking, and smoking opium. He also started to commit burglaries and robberies. A friend named Benny helped him on a few thefts; he also threw parties-Himes met Jean Johnson, his first wife, at one. But this fast life came to an end when Himes reached Chicago.

Himes entered prison at the age of 19, yet the experience didn’t slow him down. He helped oversee the convicts’ gambling activities, settling disputes and paying off the guards. He saw a lot of violence. In The Quality of Hurt he recalled, "Two black convicts cut each other to death over a dispute as to whether Paris was in France or France in Paris. I saw another killed for not passing the bread. In the school dormitory a convict slipped up on another while he was sleeping and cut his throat to the bone; I was awakened by a gurgling scream to see a fountain of blood spurting from the cut throat onto the bottom of the mattress of the bunk overhead." When he disobeyed guards, he suffered whippings to his head, periods in solitary confinement, and starvation rations. But with his mother’s encouragement, he began to write short stories. He first submitted these stories to black newspapers and magazines like Abbott’s Monthly and the Pittsburgh Courier. Then in 1934 Esquire published his short stories "Crazy in the Stir" and "To What Red Hell." According to the biography The Several Lives of Chester Himes, his success earned him some respect from his fellow inmates.

After his release in 1936, Himes was paroled to live with his mother, who had moved to Columbus to be near the prison and also to help his brother Joseph while he studied at Ohio State. But Himes picked up where he had left off. His mother discovered he’d been smoking marijuana and reported him to his parole officer, who sent him to live with his father in Cleveland. The change of environment-which separated him from his cronies-helped Himes. He started working again and resumed writing. In 1937 he married Jean Johnson. Eight years later, he finished If He Hollers Let Him Go.

Himes spent the next two years completing his second novel, Lonely Crusade, about the struggles of a black union organizer. But this book was also a commercial failure. Himes began to feel sorry for himself; he blamed his first two publishers for not promoting his books, and he felt inadequate because his wife was able to secure management-level jobs. He and Jean separated in 1952. The following year he boarded a ship for France and dedicated the next few years to travel, drinking, and women.

In late 1956, Himes wrote, "my main occupation was the search for money." While hitting up publishers for any royalties that may have been owed to him, he met Marcel Duhamel, a publisher of pulp fiction who persuaded him to write a detective novel. Duhamel gave Himes $125 on the spot and later came up with another $1,000. The first of his detective stories, The Five-Cornered Square, introduced his two most famous characters, Coffin Ed Johnson and Grave Digger Jones, who have to walk a tightrope, working on a mostly white police force and battling criminals in Harlem. The Five-Cornered Square told the story of a Harlem man who falls for a female con artist; it won France’s La Grand Prix du Roman Policier for the best detective novel of 1957.

The book marked a turning point in Himes’s life. Plagued by financial problems for much of his writing career, he had accused U.S. publishers of not paying him royalties while he was in France. At last he found an agent, Rosalyn Targ, who helped him get paid for his work. And he reached some stability in his personal life by settling down in 1962 with Lesley Packard, a white Englishwoman who worked as a librarian and wrote a shopping column for the Paris edition of the New York Herald Tribune. Six years later, they moved to Moraira, Spain, and they married in 1978 after Himes finally divorced his first wife. He died in Moraira in November 1984. He spent his last months worrying about his literary reputation.

Life had given Himes some rough edges. Cynical to the end, he believed people were capable of anything. In "To What Red Hell," a fictional account of a fire he witnessed in prison, two inmates encounter a dead convict lying on the ground and decide to rifle his pockets. John A. Williams acknowledged Himes’s tough side in the introduction to his 1969 interview with the writer, later collected in the book Conversations With Chester Himes: "He is a fiercely independent man and has been known to terminate friendships and conversations alike with two well-chosen, one-syllable words." Himes’s writing is similarly terse and street-smart, avoiding the use of symbols. His prose is blunt and unflinchingly harsh. He could be violent. In both volumes of his autobiography he admits to striking women.

He could also be charming; his friends were loyal. And he could be tenacious; he was known for his willpower. After a publisher printed 400 limited-edition copies of Himes’s novel A Case of Rape in 1980, he spent several days signing the copies, even though he could barely move due to Parkinson’s disease.

Himes used writing as a form of therapy. He focused on the struggles of black male characters who ranged from losers or victims defeated by whites to strong men who occasionally triumphed over obstacles. Racial conflict is a central theme. In his second autobiographical volume, My Life of Absurdity, he argued that racism not only psychologically damages blacks but causes bizarre events in their lives. "If one lives in a country where racism is held valid and practiced in all ways of life eventually, no matter whether one is a racist or a victim, one comes to feel the absurdity of life….Racism generated from whites is first of all absurd. Racism creates absurdity among blacks as a defense mechanism." He defended the use of violence in his work by arguing that America is a violent country. It’s often been said that he depicted white and light-skinned black women negatively because of his unresolved feelings toward his mother. This seems especially clear in his most autobiographical novels. In The Third Generation, the light-skinned mother calls her darker-complexioned husband a "nigger."

The protagonist in "Mama’s Missionary Money," finds a place in the sun the wrong way. He starts stealing money from his mother’s black bag and buys food and gifts for his friends in a southern town. He knows his mother will eventually find out the money is gone, but he can’t stop once he’s popular. He keeps taking it. "He wouldn’t think about what was going to happen when it was all gone. He was king of the neighborhood. He had to keep on being king." At the end of the story, his parents discover the money is missing and both whip him simultaneously.

Dick Small, the main character in Himes’s story "Headwaiter," has achieved some status as a supervisor of waiters in a hotel dining room. But he pays a psychological, rather than physical, price-he has to work hard to keep his composure while serving demanding white customers. The enforced docility corrupts his very being. Himes describes Small’s appearance after he fires another one of the waiters. "Then he shook it all from his mind. It required a special effort. He blinked his eyes clear of the picture of a dejected black face, donned his creased careful smile and pushed through the service hall into the dining room. His head was cocked to one side as though he were deferentially listening."

Himes based the novel If He Hollers Let Him Go on his periodic stints working in the Los Angeles shipyards. The lead character is a black supervisor tormented by nightmares, which are caused by both his hatred and his fear of whites. After a white woman refuses to work with his all-black crew, he gets demoted for cursing at her. The situation is further complicated by the pair’s mutual attraction. Near the end of the novel, the supervisor decides to put aside his fears, get married, apologize to his coworker, and ask for his old job back. Everything goes according to plan, until he’s trapped alone in a room with the white woman. She falsely accuses him of rape, and he is beaten by a mob. He accepts a judge’s offer to enlist in the army in exchange for dropping the charges against him.

Himes presents yet another absurd situation in the novel Run, Man, Run, which was based on an incident he witnessed in New York. The world of Jimmy, a black waiter, turns upside-down after he finds the bodies of two coworkers who were gunned down by a white detective. Jimmy goes into hiding, but the detective manages to learn his whereabouts and even beds the waiter’s fiancee. Near the end of the book, the detective is confronted by his brother-in-law, another policeman, and confesses to the murders. He says he was drunk one night, forgot his car’s location, and falsely accused the men of stealing it because they were black. He accidentally shot one of the men and then shot the other to cover up the crime. After the confession, the good cop kills the bad one.

The novel provides a wonderful example of Himes’s grim, slightly macabre prose. Early in the story, the rogue detective shoots his first victim, who falls and upsets a tray of turkey gravy. The gravy lands on the victim’s head. The detective takes it in: "Poor bastard, he thought. Dead in the gravy he loved so well."

The Coffin Ed Johnson and Grave Digger Jones stories were ostensibly pulp novels written for quick cash. But Himes later argued the novels represented his best work. He may be right; the series combines surreal circumstances with strong characters.

In one novel from the series, The Real Cool Killers, Coffin Ed and Grave Digger search for the murderer of a white man who frequented Harlem’s seedier spots. They focus on a gang whose leader, Sheik, has kidnapped Coffin Ed’s daughter. The case appears to be wrapped up after Coffin Ed shoots Sheik, but Grave Digger figures out a young girl killed the white man because he was a child molester. Grave Digger stands up to the city’s police commissioner when shielding her identity. "I say the killer will never kill again and I’m not going to track him down even if it costs me my job."

In Cotton Comes to Harlem, the two detectives solve a series of murders committed by criminals trying to find a bale of cotton. The cotton contains $87,000 conned out of Harlem residents who think they’re buying tickets to Africa. The detectives catch the gangsters, but they never find the money. Yet they persist in trying to repay the residents. They accomplish this by blackmailing one of the murderers-a white man from Alabama. The Alabaman is shocked by their actions:

"Incredible! You’re going to give them back their money?"

"That’s right, the families."

"Incredible! Is it because they are nigras and you’re nigras too?"

"That’s right."

At the end of the novel, the detectives learn a junk collector found the money inside the cotton and emigrated to Africa.

Himes wrote the novel in 1965, during a period in which he began to reflect on his own life experience as well as the plight of blacks in America. He argued that blacks had to stay put and thrive. In the interview with Williams, Himes said, "The American black man is very different from all those black men in the history of the world because the American black has even an unconscious feeling that he wants equality. Whereas most of the blacks of the world don’t particularly insist on having equality in the white community. But the American black doesn’t have any other community. America, which wants to be a white community, is their community, and there is not the fact that they can go home to their own community and be the chief and sons of chiefs or what not. The American black man has to make it or lose it in America; he has no choice. That’s why I wrote Cotton Comes to Harlem. In Garvey’s time, the ’Back to Africa’ movement had an appeal and probably made some sense. But it doesn’t make any sense now. It probably didn’t make sense even then, but it’s even less logical now, because the black people of America aren’t Africans anymore, and the Africans don’t want them."

Article “Harsh Words,” Courtesy Michael Marsh (originally appeared in the Dec 4, 1998 issue of the Chicago Reader).