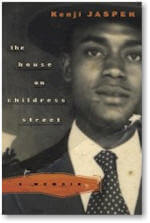

House on Childress Street:

A Memoir of My Grandfather

House on Childress Street:

A Memoir of My Grandfather

Click to order via Amazon

ISBN: 0767916794

Format: Paperback, 272pp

Pub. Date: January 10, 2006

Publisher: Harlem Moon

Excerpt

It starts out so small: a square of wood-topped table, a white candle and a

glass of water. The table and the area around it are sectioned off with a curved

line of cascarilla chalk. Then for good measure you add framed pictures or the

written names of all of those in your family who have passed on.

In doing this, if you believe in it, you are creating a bridge between our world

and the other, a portal through which one can communicate with their ancestors.

I have chosen a photograph of the man I wish to hear me, one I took myself as he

turned the corner from his kitchen into the dining room on one of my usual

Sunday visits.

Now there is movement all around me, the brushing of invisible leaves across my

arms and legs. Intuition tells me that he is nervous, that he doesn't want

anyone putting his story into words. So I speak to the deceased. I call his

name: Jesse James Langley, Sr., my grandfather. The spoken word is more powerful

than we will ever know. The invisible leaves center themselves. He is listening.

I tell him that this is not about judging him, that I am not some muckraking

journalist looking to ruin his memory. I tell him how much I love him, that the

world should know all that he did to make a better life for his family. I tell

him all of this knowing that it will not make him any less apprehensive towards

what I have chosen to do. I do it out of respect. Without him I wouldn't be

here. But to start to give you a clearer idea of who he is, I'll tell you a

story:

I was 16 years old and I needed a car. My senior year of high school was on the

way and I was determined to join the ranks of my homeboys who 'whipped it' to

their place of adolescent learning. An entire summertime of having to beg my

mother to lend me her car had placed me on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

I wanted to be able to see that girl across town (if there was every going to be

one) at 9 pm on a Tuesday. I wanted to drive to my father's house in the county

on the weeks I wasn't staying with him. I wanted emancipation. And I'd been

saving that whole summer to secede from Angela Jasper's union.

I was tired of asking, sick of those nauseous moments when the 'to be or not to

be' was all up to her. I hated answering all the questions. I hated when my

still-developing values clashed with the current law of the land. I wanted to

escape, turn a key and head towards the sunset, set out for adventure and a life

my own. So, armed with a handful of hundreds, I was ready to score the ride of

my dreams at the Capital City Car auction, an aircraft hanger-like building

stocked with lemons and junkers to be auctioned off every other Saturday of the

month.

Both Mom and her brother Junie had told me that my grandfather was the man when

it came to cars. Every ride he'd owned had been bought used, fixed up and driven

for a million miles without ever spending as much as it would've cost to get it

new. Thus anything he said in relation to the automotive was law, and I was to

abide if I knew what was good for me.

My grandfather stood silent as the cars came in. I watched him, watching them,

trusting in his expertise, because all I cared about was that the tape deck

worked and that it started up when I turned the key.

A periwinkle '88 Chevy Corsica came into, a near twin to the one my mother

owned. It had the all-important tape player and a good set of speakers. The

paint wasn't chipped and the engine hummed like a housewife doing laundry;

everything a teen boy could have wanted in getting him from A to B.

'We're gonna get that car for $500,' he informed me, those being nine of the

maybe 30 words he'd uttered in the day thus far 'But no matter what they start

talkin', we ain't goin' past $500.'

There was a clamoring of voices as the object of my affection stopped right in

front of us. Bidding hands rose as the auctioneer announced a starting price of

$200. It then rose to $350, and then $410. But I didn't watch the crowd. I

didn't even stare at the idling specimen itself. My eyes were on my mother's

father, he who remained stoic despite the closeness of our target number.

Didn't he know how much was riding on this outing? Summer was ending. Senior

year was calling. I was going to kill myself if I had to come out of one more

house party and see my father dozing off at the curb with his hazards on. This

man had to save the day.

Yet, the next thing I knew the numbers were at $550, $620, $725 and finally at

$800 when some lady the size of two Della Reeses rolled off with my car.

I turned to my supposed savior in disbelief, waiting for an apology, an

explanation, or anything other than his dead silence. I could've matched the

woman's offer. I had enough dough, even if it would've left me in the lurch for

tags and registration. But there was no way that I was going to go against him,

because no one did, not my mother, not my uncles, and not even his own wife.

Besides, everything else that came up for bid was garbage, and he and I both

knew it. So when the last ride came up to the front, a '78 Honda Accord with the

worst rust problem I'd ever seen, he motioned me towards his car without a word.

It was over.

My mind floated somewhere between anger and disbelief, trapped between having

respect for my elder and wanting to put him in a sleeper hold. Maybe he'd seen

something. Maybe his Mr. Goodwrench spider sense got wind of some flaw invisible

to my virgin eyes. If so, I needed to hear him say it. I needed to hear him say

anything.

'How much did they sell that car for?' he asked as we headed over the bridge

toward Mt. Olivet Road, the gateway to his home.

'Eight-hundred,' I said, impatiently awaiting his explanation. He looked

straight ahead for a beat, as if he were contemplating his reply. I had exactly

eight hundred-dollar bills in my pocket.

'You know, it might have been worth that,' he said casually. 'It might've been

worth goin' up to 800.'

I couldn't believe it, that now he was now backpeddling, that he was now

admitting that he might've made a mistake as if it didn't matter, as if his

first grandson wasn't going to suffer severely as a result of his choice to

shake the dice.

But to him, it wasn't about me, or the car. It was about his sense of how things

should be. If he couldn't get the ride for $500, then he wouldn't get it at all,

no matter how much I, his eldest grandson, would be disappointed. He needed to

have things his way. My dreams were an inadvertent casualty. It would be another

four years before I got my first ride, a shabby '88 Honda CRX with hubcaps the

previous owner had spray-painted blue.

I never told him how I felt that day because he didn't seem to be one who would

respond to emotion. I imagine that his reaction to a crying child in his arms

would be to hand it to the closest woman, because she would know what to do. In

his mind, things were what they were, and you just had to deal with them.

The episode came and went. Life went on. My mother told me that this was how my

grandfather did things, and that I, like everyone else, had to get used to it.

Besides, I might need him again somewhere down the line. Sure enough, I did.

More than once.

Anyone who knew Jesse Langley can tell you a story about his resolve, about his

reticence, and about how he could always be found on his front porch smoking a

square and watching time float away with that stream of smoke headed towards the

stratosphere. But they can't tell you how he came to be that way, the hows and

whys of who made him what he was. Neither could I, at least not yet.

As a boy I stayed away from him as much as possible. I dreaded my obligatory

trips to his upstairs abode to say ''hello'.' He seemed so cold and distant, as

if he was less of this world than some other, as if he were biding his time for

some greater journey beyond his years spent on this particular plane. He treated

those he loved most with what seemed to be the utmost ambivalence, as if they

were both treasure and burden all at once. How could my mother have been his

child? How could my grandmother live with him for so long?

This was a constant meditation within my developing mind. As I went from boy to

man it got more difficult to bear the uncertainty that washed over me whenever

he entered a room. Would he be naughty or nice? Would he help or hurt? It often

seemed as if one never came without the other, and for the very short life of me

I couldn't understand why.

By the time this is published, I will be 30 years old, close to the age he was

when my mother, his first child, was born. I want a wife and a family and a home

with my name on the deed. But I also want peace, which is something I don't

think he ever had. It's often said that you can't have a future until you know

your past, a perfect statement to describe the descendants of a people stolen

from the land and culture that defined them. Thus, it just as easily describes

me.

I am searching for a man who is part of myself, a life forever etched into my

genetic code like letters chiseled into smooth stone. I am his future but I do

not know his past., Thus I cannot go forward until I do.