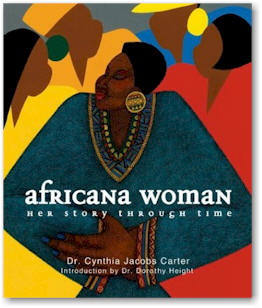

Africana Woman. Her Story Through Time.

Africana Woman: Her Story Through Time

Africana Woman: Her Story Through Time

Click to order via

Amazon

Cynthia Jacobs Carter, Dorothy Height (Introduction)

ISBN:

0792261658

Format: Hardcover, 256pp

Pub. Date: November 2003

Publisher: National Geographic Society

Chapter 1: Royalty

|

From the dawn of civilization, Africa’s royal women have shown themselves to be intelligent, resourceful, courageous, passionate�and sometimes vulnerable. Although born and raised in different parts of the continent, they all shared a common desire to forge their own destinies and to live on in eternity. Their astounding stories, true and fabled, survive today to reveal their accomplishments and their legacies.

|

|

By 1500 B.C., Egypt’s great pyramids had stood for more than ten centuries. Egypt had survived periods of plague, pestilence, and even opulence and now was enjoying a renaissance. The Hyksos�invaders from southwest Asia who had ravaged and controlled Egypt for decades�had been driven from Lower Egypt, the land encompassing the Nile River Delta and its northern valley. In addition, Egypt’s armies were marching south to conquer Nubia, a fertile land that stretched along the banks of the Nile, near present-day Libya. While Egypt added new territories to its boundaries, it also grew internally�to become the undisputed center of culture and politics in the larger eastern Mediterranean world. It was the beginning of the New Kingdom�a period of great Egyptian power and wealth that would last four centuries, from around 1539 to 1070 B.C. Hatshepsut, one of Egypt’s most fabled rulers, lived in the early years of this glory.

Daughter to Pharaoh Thutmose I and Queen Ahmose-Nefertere, Hatshepsut was born around 1500 B.C. Beautiful and intelligent, Hatshepsut knew a life of great wealth and privilege. When Thutmose I died around 1492 B.C., the Egyptian court insured the continuation of the royal bloodline by wedding her, a full-blooded royal, to her half-brother. Thutmose II was the new pharaoh and the son of Thutmose I by a lesser wife. (Incestuous marriages were common among Egyptian royals since the women carried the royal blood.) Though still a very young woman, Hatshepsut ruled as Thutmose II’s principal queen.

She of Noble Bearing � Great Royal Spouse � Daughter of the God Amun � First Lady of the Two Lands. Hatshepsut proudly wore these titles as queen. She stayed in the background when Thutmose sat on his throne, but her intelligence was always evident. Thutmose frequently left Hatshepsut in charge when he journeyed abroad�leading successful military campaigns into Syria and Nubia that acquired both land and great wealth. Before Thutmose II died, he named his only son’seven-year-old Thutmose III, born to a harem girl�his successor. Since Thutmose III was too young to rule on his own, the Egyptian high court designated Hatshepsut as co-regent. A wise and ambitious woman, Hatshepsut understood her position and ruled judiciously.

Although Hatshepsut could have declared war on her neighbors, she chose to focus instead on national affairs. She built education and arts facilities. She dismantled the main army and sponsored peaceful diplomatic expeditions into Punt, Asia, Greece, and strategic areas on the continent of Africa. Later, caravans and ships followed, trading in gems, ivory, ebony, oils, spices, incense, and even trees. Hatshepsut continued to rule even after Thutmose III came of age. It appears that they split the duties: She oversaw the administration while he commanded the military. A few years later, however, with Thutmose III involved in military campaigns, Hatshepsut crowned herself pharaoh.

She used to her advantage the Egyptian belief that a royal birth resulted from the union between the pharaoh’s mother and Amun-Re, the supreme deity. (Some experts believe that this notion, a heavenly god fathering a human child, may have sowed the seeds for Christianity.) Hatshepsut claimed that Amun-Re had come to Queen Ahmose-Nefertere in the human form of her husband, Thutmose I. Since she, Hatshepsut, was the child of that union, she concluded that she was the rightful child to rule all of Egypt. To legitimize her claim to the title of pharaoh, she ensured that the people of Egypt recognized her as pharaoh by always appearing in public in full royal male regalia: a simple robe, red-and-white crown, royal wig, and a nems (a striped cloth placed around the wig). She also donned a false beard, facial hair being strictly forbidden to all but the pharaoh. She even claimed a pharaoh’s privilege and had a burial tomb carved out for herself in the Valley of the Kings, adjacent to that of Thutmose I.

As peace thrived under Hatshepsut’s reign, wealth grew. Hatshepsut spent her fortunes on monuments to the gods, both to honor them and to ensure her prominence in the afterlife. Senmut, a renowned architect and astronomer of the era�reportedly a Black man and her lover�built several temples and obelisks upon her instruction. Today, Egypt claims many of Hatshepsut’s commissions among its greatest wonders of the past. One such marvel is the large mortuary temple built of limestone at Deir el-Bahari intended to honor herself and her human father, Thutmose I. The temple steps back into the cliff in three levels, each faced by a colonnade and adorned with relief sculpture that depicts in great detail the glory of the expedition to Punt that Hatshepsut financed.

Another monument, the Red Temple at Karnak, housed the statue of Amun-Re. Each year during the Opet�a celebration honoring the new year�temple priests carried Amun-Re’s statue from the Red Temple to his shrine at Luxor to receive the worship of his subjects. In return for their loyalty and offerings, Amun-Re was to shed favor upon them for the next year. Four obelisks built of red granite from Aswan and inscribed with hieroglyphics in honor of Amun-Re flanked the Red Temple. They stretched to the heavens in height and splendor, their surfaces of electrum glinting in the sun. One still stands today after 35 centuries, a hint of electrum still adorning its surface; its inscription begins:

I have done this with a loving heart for my father Amun;

Initiated in his secret of the beginning,

Acquainted with his beneficent might,

I did not forget what he had ordained.

My majesty knows his divinity,

I acted under his command;

It was he who led me,

I did not plan a work without his doing.

Hatshepsut died in 1458 B.C. after effectively ruling for more than two decades. It is not known how Hatshepsut died. What is known is that despite her opulent public life, Hatshepsut may have had one secret love. Discovered in her tomb, lying beside the great ruler, was an ebony-skinned baby, mummified and wrapped in the royal tradition with Hatshepsut’s insignia.

Following Hatshepsut’s death, Thutmose III assumed the full role of pharaoh. Thutmose III is said to have despised his stepmother and her reported relationship with Senmut. He felt ignored and scorned by Senmut, and he believed that Hatshepsut squandered his heritage at Senmut’s directive. Perhaps in retaliation, Thutmose III ordered destroyed many of Hatshepsut’s creations, especially where she was depicted with Senmut. Many temples Hatshepsut had built, as well as statues of her likeness, were defaced. On some statues the royal emblem was knocked off her headdress; on others the eyes were pecked out with a small chisel. Still, Thutmose III could not completely destroy her legacy. Her monuments�and her story�endure. Written on one of the obelisks at Karnak is her enduring declaration: �As I shall be eternal like an undying star.�

Several decades later, with Egypt still thriving under the influence inspired by Hatshepsut, Pharaoh Amenhotep III wed Tiye, a young Nubian of noble birth. Tiye was born around 1400 B.C.; her father Yuya served Amenhotep as a Master of Horse and Chancellor of the North. According to some historians, the introduction of Tiye into Egypt’s royal family changed the fate of Egypt forever�it solidified Egypt and Nubia in a bond that brought Black Africa and North Africa together. Under Amenhotep, the kingdom stretched from the farthest tip of Egypt’s New East to the Kingdom of Napata in present-day Sudan.

Amenhotep III became pharaoh around 1390 B.C. when he was 10 to 12 years old; he married Tiye, who was around the same age, shortly thereafter. He proceeded to marry many more women, forging political alliances that brought Egypt wealth and strategic military alliances. Many of his wives were of noble birth, including the daughter of the King of Babylon; however, Tiye, with her charm and beauty, was Amenhotep’s favorite wife and his principal queen. She would hold the position as the Great Royal Spouse of Amenhotep III for nearly 50 years. Because Amenhotep held Tiye in such high esteem, he proclaimed her an equal of a king�the first time a nonroyal had achieved such status. She was also the first queen depicted on even par with her husband in royal portraits.

Tiye’s husband showed her his affection in many unique ways. He had her accompany him to many events, even though royal protocol called for Amenhotep’s mother, the carrier of the royal bloodline, to accompany him to certain official ceremonies. (One can only imagine how his mother felt about having to share her time and the attention of the masses with her daughter-in-law from Nubian origins.) He built Tiye a gorgeous barge, the Splendor-of-Aten, then dug an artificial lake so she could float the craft for special ceremonies, fireworks, or whatever pleasure she desired. He also commissioned for her a great complex of structures in western Thebes; it is believed Tiye resided in the southeast quarter of the complex in what is called the South Palace. Amenhotep went even further by erecting a splendid temple dedicated to her worship in the Nubian city of Sedeinga, on the west bank of the Nile in present-day Sudan.

Amenhotep loved and trusted Tiye so much, and so respected her intellectual capabilities, that he considered her a trusted advisor and confidante in affairs of state. He often left her in charge while he traveled on missions to increase Egypt’s honor; his faith in her judgment was proven correct time and again when she ruled alone for long stints.

When Amenhotep died in 1353 B.C., Tiye’s power and influence did not end as was the case for many previous queens. In fact, when Tiye’s son Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV) took the throne, she became secretary of state, a position second only to the pharaoh. Leaders from other countries routinely conferred with Tiye on matters regarding international relations, remembering and respecting her earlier actions as queen to Amenhotep. Tushratta, King of Mitanni, beseeched Tiye to influence Akhenaten to honor the agreements made between himself and Amenhotep: �You are the on[e, on the other ha]nd, who knows much better than all others the things [that] we said [to one an]other. No one [el]se knows them (as well).� Eager to continue the goodwill between their two kingdoms, he added �You must keep on send[ing] embassies of joy, one after another. Do not cut [them] off.� Tiye served as the liaison between the courts at Thebes and Amarna, Akhenaten’s new capital. Meanwhile, Akhenaten, encouraged by his mother, preoccupied himself with religious reform, proclaiming for the first time in human history the idea of a single god. He named Aten, the solar disk and a lesser god to Amun-Re, the supreme deity. He devoted himself to his beliefs and the building of Amarna, which would be the center of worship for Aten. Tiye died around 1340 B.C., but her groundbreaking accomplishments in matters of royalty and affairs of state live on.

Just as Egypt claims Tiye as a queen, Ethiopia claims Makeda, the Queen of Sheba, as one of its own. Makeda (or Bilqis as she is known in the Islamic world) is considered by Ethiopians to be the mother of the Ethiopian royal bloodline that commenced in the tenth century B.C. and continued to modern times.

The story of Makeda is written in the Bible, the Koran, and the Kebra Negast (Glory of Kings, an Ethiopian epic), each with subtle variations. According to legend, Queen Makeda learned of the wisdom of Jerusalem’s King Solomon from a merchant prince named Tamrin, who had been engaging in trade with that king. Old Testament scripture states in I Kings that when the Queen of Sheba heard of the fame of Solomon, she decided to prove him with hard questions. She set out to see the king, carrying with her an abundance of gold and spices. Like any visiting dignitary, Makeda did not want to arrive empty-handed. Her gifts were both an offering of peace and a demonstration of her prosperity. The Song of Solomon in the Bible has Makeda allegedly saying upon her arrival, �I am black but comely, O ye daughters of Jerusalem.�

King Solomon loved women and reportedly had a harem of more than 600 wives and concubines. He was instantly struck by Makeda’s beauty and wished to claim her for his own; however, the Queen of Sheba was bound to chastity. So enthralled was Solomon by the Black queen that he respected her wishes. Still, he seldom left her side. He lavished her with feasts during which the two of them dined and talked every night until dawn; he commissioned for her an apartment made of crystal and had a throne for her placed at his side. For six months Makeda witnessed his decisions, actions, and interactions with his people. Only then, as said in I Kings 10: 6-7, was she convinced of his wisdom:

And she said to the king, It was a true report that I heard in mine own land of thy acts and of thy wisdom.

Howbeit I believed not the words, until I came, and mine eyes had seen it: and, behold, the half was not told me: thy wisdom and prosperity exceedeth the fame which I heard.

Then, according to the Kebra Negast, she announced that it was time to return to Ethiopia and her people. They needed her. Her announcement saddened Solomon; he had hoped to convince her to consummate their union, for he very much desired a son born of this strong, intelligent, and beautiful woman.

The Kebra Negast relates that King Solomon created a situation to fulfill his dearest wish. He made Makeda’s final night more festive than all the previous days and nights she had spent in Jerusalem. He lavished her with everything that his royal throne could summon. Fiercely attracted to Solomon, Makeda’s resolve finally crumbled, and she welcomed the king into her bed. The next day, Solomon supposedly gave Makeda 6,000 chariots laden with gifts, and a vessel that traveled in the air. Upon returning home, Makeda learned she was carrying Solomon’s child; she named him Menilek, the Son of Wisdom, to honor his father.

When Menilek reached manhood, Makeda gave him a ring and told him to seek his father in Jerusalem. The young man did as his mother requested. Legend says that Menilek spent time with his father, learning from his wisdom. Eventually the young man returned to his mother’s people in Ethiopia, having been anointed a king in Jerusalem, to found the Solomonic dynasty. The wisdom and intelligence of both his parents was evident in his reign. Whether fact or fiction, Ethiopia proudly claims that the Solomonic dynasty, begun with Menilek and unbroken until the death of Haile Selassie in 1974, descends from King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

Hundreds of years after Hatshepsut, Tiye, and Makeda had become part of Africana history, Yennenga of West Africa came forth. According to oral histories passed down from generation to generation, Yennenga was born the daughter of King Madega of Dogomba, a kingdom that covered much of present-day Ghana. It is believed she lived some time between the 11th and 15th centuries.

The histories tell us of Yennenga’s strength of character and loyalty to her father. She commanded her own battalion and the royal guard. Yennenga performed many heroic acts in defense of her father’s kingdom, frequently fighting by her father’s side. However, as she grew into a young woman she longed for more than the glory of battle. She wished for a family. She made her father aware of her feelings, yet he quickly dismissed any suitors that dared approach. Yennenga decided to chart her own destiny.

One night, dressed as a man and escorted by loyal retainers, she left home on the back of a wild stallion. The party traveled for days. Then one night, exhausted, Yennenga could go no further; she and her entourage happened upon a tent in a region peopled by the Bousanc�and stopped. Still in disguise, Yennenga accepted the hospitality of the owner. He was Raile, a Mande prince in exile from Mali, where his father had been deposed. Legend has it that Yennenga kept her true identity hidden. She stayed with Raile for days, listening to him talk about his conquests on elephant hunts. Finally, her long hair fell from under her helmet, revealing her to be a beautiful princess, not a prince as Raile had believed.

The two married and lived in his tent. A year or so later, she bore a son; the couple named him Ouedraogo’stallion�for the horse that carried Yennenga to her husband. When Ouedraogo was 17, Yennenga took him to meet her father. Apprehensive at facing the king, Yennenga was relieved to find him elated to see her, to discover he had long forgiven her for leaving. Reunited in spirit with her father, Yennenga returned to Raile and the life she had made for herself. However, she left Ouedraogo in her father’s care so he could learn all that King Madega could impart. Some time later, when Ouedraogo felt sufficiently educated, he requested permission to leave. The king then revealed to Ouedraogo that he was next in line to the throne, but this grand gesture was not enough to satisfy the son of Yennenga. Ouedraogo, much like his mother, wished to follow his own path. He desired to establish his own kingdom. The king, determined not to make the same mistake twice, gave Ouedraogo his blessings and a large troop of men-at-arms to command.

After stopping to pay homage to his mother and his father, Ouedraogo set out to found the Mossi Kingdom. The kingdom once covered much of present-day Burkina Faso and northern Ghana, and still exists today. From the 11th century to the present, the kingdom has known only one dynasty: the descendents of Ouedraogo�a chain of 30 monarchs. By following his mother’s example, Ouedraogo honored her. In legends, the Mossi Kingdom is known as the tree born of the trunk of the great warrior Yennenga. Griots (storytellers of tribal histories) sing of the young girl of 14 who rode bravely into battle on horseback, her hair floating in the wind like the mane of a lion. To this day, out of respect for Yennenga, all Mossi warriors revere the lion and refuse to kill it except in self-defense. Yennenga lives on in the many business establishments, roads, and public gardens that bear her name and in the statues that abound.

Griots farther west in West Africa tell the story of another young woman who epitomizes the strength and character of the Africana woman. In the late 1600s, Amina Kulibali, the young daughter of the new king of the Massaleke people of southeast Senegal, was chosen to marry the eldest son of the late king who had most recently ruled their land. One night, Amina’s fianc�, unwilling to wait the required year for marriage, slipped into the bed of his intended. Shortly thereafter, Amina learned she was with child; filled with shame and aware of the disgrace and humiliation it would bring upon her father, she fled.

She took a few servants and many bags of gold and traveled deep into the neighboring territory of the Gambia, where many of the same tribes as those in Senegal�including the Wolof, the Serers, and the Tukulor�lived. Several months passed. Then, by chance, the heavily pregnant Amina met the king of Gabu, who thought her the most beautiful woman he had ever seen. He instantly desired her, but Amina would not again be swayed by charm. Legend says that she studied the king for some time, then declared, �If I follow you, the child who is within me will be king in the country where he will be born.� The king agreed to her terms. He was so smitten that he even disbanded his other wives so that Amina would never have cause to be jealous. Amina gave birth shortly thereafter to a girl, and to be true to his word, the king said the children of this child would be his successors. These successors, among them a great ruler named Goria and his three sisters, established a kingdom between Gambia and Gsangomar.

In the same century, but farther south, the magnificent Anna de Sousa Nzinga of Ndongo (present-day Angola) rose to prominence�first as a king’s brave daughter and later as a revered warrior queen. At the time of her birth, most likely 1581, Portuguese missionaries had converted to Catholicism many of the Mbundu, the people living in and around Ndongo. A few years later, Anna’s father, King Kiluanji, fearing that the Europeans would convert all of his people�destroying their heritage�banned missionaries from his country. In addition, he effectively cut off the Portuguese from the endless supply of Mbundu slaves they were taking and shipping to the Americas. The act amounted to a declaration of war, and set off years of conflict between the Portuguese and the people of Ndongo. Nzinga fought in many of the battles.

At the height of the warfare, Nzinga’s father died. His kingdom was placed in the hands of Nzinga’s older, illegitimate brother, Mbandi. The jealous Mbandi was aware that Nzinga commanded the respect of his counselors, as much for her diplomacy skills as for her prowess on the battlefield. Consequently he ordered Nzinga banished and her son killed. In addition, griots sing of how he ordered his women retainers to sterilize Nzinga with a sizzling hot poker. Others say that instead of a poker, they used scalding water.

A few months later, after losing battle after battle�his armies with their traditional weapons were no match for the Portuguese Army’mbandi begged for Nzinga’s help in negotiating a peace agreement with the Portuguese. She spoke their language and knew their ways. Even though Nzinga still mourned the murder of her son, and her own humiliating sterilization, she decided to come to Mbandi’s aid, though for her people’s sake, not his.

In 1622, she set off to Luanda, the stronghold of the Portuguese, to meet Correia de Sousa, the new Portuguese governor. She entered the city in a royal procession preceded by musicians and an honor guard of warrior women. The governor attempted to insult Nzinga by receiving her seated high on a dais in a large carved chair; he only provided her with cushions on the floor. Not one to be bested by wits, Nzinga quickly came up with an alternative. She clapped her hands and one of her retainers came forth, bowed on elbows and knees, and offered her back as the perfect chair. Nzinga brokered a settlement whereby the Ndongo kingdom would return Portuguese prisoners of war and help the Portuguese in the slave trade in return for sovereign recognition and the withdrawal of Portuguese forces from Ndongo lands. She even accepted the Jesuit faith and was baptized (taking the name Anna de Sousa); everyone in Luanda attended the grand ceremony. Although the negotiations were nominally successful, Nzinga doubted that the Portuguese would honor the accords. Her suspicions were shortly confirmed when the Portuguese did not withdraw their armed forces and confine their activities to the coast.

Realizing that Mbandi was an ineffective leader, incapable of holding off the Portuguese onslaught, Nzinga returned to Ndongo. She had her brother arrested’she perhaps even arranged his death by poison a few days later�and she assumed the throne, declaring herself queen. She ignored the Mbundu custom that strictly forbade women to take positions of power, choosing to treat it as a mere formality. To further establish herself on the throne, she gathered a harem of young men as her �wives,� just as a king would gather a harem of young women for his pleasure. In a final nod to Mbandi, Nzinga also avenged her son’s death by taking the life of Mbandi’s son.

From the moment she took the throne, Nzinga ruled with the heart of a warrior rather than of a diplomat. Over the next 40 years she waged intermittent warfare against the Portuguese. She led her army into battle even at the age of 60. Against mounting military pressures, Nzinga retreated to neighboring Matamba in 1656; later she agreed to the peace terms offered by the Portuguese and she voluntarily returned to the Jesuit faith. But she never stopped fighting for her people. And although her people were sometimes torn in their devotion to her because of her flagrant violations of Mbundu custom, they revered her for her courage, strength, and leadership. When Nzinga died in 1663, she was celebrated just as she had lived: as a queen. She was buried in a religious habit, and draped in her pearls-and-gold-accented royal robes.

Nearly 100 years after Nzinga ruled, a shy girl named Nandi was born in the present-day KwaZulu-Natal region of southern Africa. Quiet and unassuming, she was the orphaned daughter of the chief of the Langeni people, members of the Zulu clan. One day in the late 1780s, when she was in her early teens, Nandi encountered Senzangakhoma, the chief of the Zulu. Dazzled by his presence and flattered by his attention, Nandi shunned the Zulu tradition that said there could be no union between people of the same clan. When Nandi discovered she was pregnant, Senzangakhoma took her as his third wife. The privilege of being one of the chief’s wives, however, could not outweigh the dishonor and shame of their illicit intercourse. Both she and her son, Shaka, born of that forbidden union, were vilified. Life in the clan became unbearable.

When Shaka was six years old, Nandi and Senzangakhoma separated; she returned to the Langeni with Shaka. The Langeni were no more forgiving. She and Shaka met the same disapproval, but Nandi refused to flee. For the shame she had brought upon her family, she chose to bear the recriminations: humiliating tauntings and harassments. As a boy, Shaka was constantly teased and beaten by the other boys in the kingdom. In 1802, the Langeni cast out Nandi and Shaka. Eventually the Dletsheni, a subclan of the powerful Mtetwa people, gave them shelter; but they still were not safe from hateful words or actions. Nandi had finally had enough. She drew on her inner strength to rise above the injustices that had been meted out to her. She proceeded to devote her life to one pursuit: raising her son to become the greatest warrior of all time. She gave Shaka a stick and instructed him to hit those who hit or even looked at him. She would come to regret those instructions.

Shaka grew to manhood and became a warrior for the Mtetwa; he excelled on the battlefield. When Shaka turned 29, Dingiswayo, the overlord of the Mtetwa, released him from military service and sent him to take command of the then faltering Zulu clan. Using his military prowess, Shaka turned the small clan into a great nation of warriors. The Zulu nation grew through political alliances and the assimilation of clans his armies decimated. Thousands of people in neighboring clans were killed as Shaka increased the nation’s territory. While many people, including his own, found him fierce and tyrannical, the Zulu nation took pride in his abilities to fight off the encroaching Europeans.

Throughout his childhood and into adulthood, Shaka had maintained a strong attachment to Nandi. Her love supported him and pushed him to the heights, yet she exerted a gentling hand. It is said that as Shaka’s thirst for power and bloodshed grew, Nandi could no longer appeal to his humanity. In 1827, she died as a queen mother who had lost touch with her son, the greatest warrior of his time. Her death profoundly affected Shaka; he was consumed with grief. He ordered the entire Zulu nation to mourn Nandi’s death for one year. Nandi, who had been so unassuming at birth, then commanded in death the reverence of an entire nation of warriors.

In Her Own Words: Hatshepsut

This formidable ruler of Egypt’s New Kingdom built obelisks at Karnak to honor her divine father, Amun-Re. She had them inscribed with her words, as below.

|

|

It is the King himself who

says: I declare before the folk who shall be in the future, Who shall deserve the monument I made for my father, Who shall speak in discussion, Who shall look to posterity� It was when I sat in the palace, And thought of my maker, That my heart led me to make for him Two obelisks of electrum, Whose summits would reach the heavens� |