-

Posts

2,380 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

90

richardmurray's Achievements

Single Status Update

See all updates by richardmurray

-

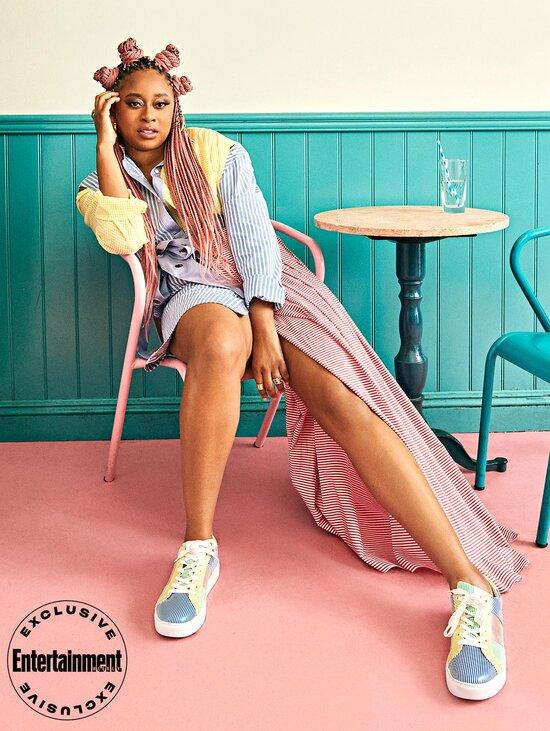

Book Smart: Phoebe Robinson on ghosting, refusing failure, and shaking up the publishing industry

The comedian, who launches her own book imprint this month, pens an essay for EW.

By Phoebe Robinson

September 16, 2021 at 12:00 PM EDTDear reader, yes, I look fabulous in these photos, but please know that I wrote this essay while pantless and seated on my couch, rocking a push-up bra (for who? I'm by myself ) and listening to Omarion's "Ice Box" because there's never a wrong time to live the way I was living in 2006. Anyway, here I am in Entertainment Weekly tasked with summarizing, IN 1,200 WORDS OR LESS, (1) my journey toward launching my literary imprint Tiny Reparations Books with my third book, Please Don't Sit on My Bed in Your Outside Clothes (Sept. 28), and (2) my opinions on the ever-changing publishing landscape. Insert shocked emoji followed by the Kanye West lyrics: "Poopy-di-scoop/Scoop-diddy-whoop." Basically, this writing assignment initially caused my mind to overload with a barrage of thoughts that all I could make out were some poops and scoops. Still, I'm not one to back down from a challenge, so here goes.

It was 2014. I told my now-former manager that I wanted to write a book. Her response: "Well you're not famous, so you shouldn't be writing a book." Did I fire her after she said that? Nope! My goofy ass kept working with her for several months until she GHOSTED ME because I was still not famous. Let's soak that in for a moment. I continued paying someone 15 percent of what I make to tell me I ain't s---. LOL I will unpack that in therapy right after I work through the fact that I wore foundation eight shades too light for my skin tone because I got my makeup done at the mall before I went to senior prom. ANYWAY! The point is: I was a struggling stand-up comic with a dream and zero knowledge of how to make it happen. And because many famous authors, movies, and TV shows romanticize what it's like to write books, I thought it would be easy, aside from the occasional bout of writer's block. I was wrong! Writing and selling a book proposal to a publisher ain't sexy! Writing a book ain't sexy! Promoting a book ain't sexy! In fact, the whole process — the idea phase straight up to publicaysh — is mostly like lovemaking after a hearty Thanksgiving dinner, a.k.a. sometimes tryptophan won't let you be great and the same can be said for the world of publishing. Let me explain.

Back in 2015, my literary agent Robert and I shopped around my proposal for You Can't Touch My Hair and Other Things I Still Have to Explain. Imprint after imprint rejected it because they claimed that books by Black women don't sell (wut?) and are not relatable (to whom, DAVE?), and that no one is interested in funny-essay collections by Black women (wut? the sequel). In the end, Plume was the only imprint that wanted me, and as Lady Gaga taught us, ya only need one person to believe in you, boo! Anyway, cut to 2016. You Can't Touch My Hair was on the New York Times best-seller list for two weeks, and the very places that turned me down emailed Robert asking why we never tried to sell my proposal to them because "they would have loved to publish me." He politely reminded them that he did and what their responses were. And while it's good for the ego to prove a bunch of close-minded and biased heauxes wrong, I kept thinking about all the women, POCs, and queer people who don't end up with this happy ending, let alone the opportunity to get their writing published. I wanted to do something with what little power I had, but then life happened.

My TV career grew thanks to my 2 Dope Queens specials for HBO. I fell in love. Finally traveled after being in debt for over a decade. Had creative projects fall apart. Got a Peloton. JK. But also, #PelotonIsLyfe. Was in early talks with Plume to partner with me and launch an imprint. And yes, of course, coronavirus. It made the world stop. All the plans everyone had vanished. Like most people, I clung to anything that felt "normal," and that "anything " was books. Every morning, I would get up early and read for hours. Books became my escape, an oasis, a new way of understanding our drastically different world, and most important, they brought me immense joy. Robert could sense this whenever we chatted on the phone just as friends, and when I told him about my idea for Please Don't Sit on My Bed, he said that I should launch my imprint and that could be the first book published. #UltimateFlex, but also, hmm. In the face of the summer of social reckoning spurred by the murder of George Floyd, having an imprint seemed… irrelevant? But then I reminded myself that every time I read, I felt inspired that there was something more than the collective trauma we were enduring. If anything, the suffocating bigness of COVID and police brutality illuminated how special and important books are. So having my own imprint went from seeming trivial to a "why the hell not?" Given the state of the world, the worst that could happen is failure.

A word, if I may: After you've been told more times than you care to count that you don't have what it takes to achieve your goals, that you and your work are not valuable, or you're just given an emphatic "no" without any further explanation only to prove them wrong by not just knocking your goals off your to-do list, but exceeding the wildest dreams you've ever had, you start to realize that worrying about failing is not worth your time. Even if what you're going after doesn't work out, betting on yourself is the smartest and the best no-brainer thing you could do. And launching an imprint during COVID AND the reckoning AND in an industry that, to say the least, has not always embraced women, POCs, and the queer community is pretty damn smart. The contributions to the written word from these groups are ASTOUNDING, and it's my privilege to, in some small way, help them carry on the tradition.

Sure, the jury's still out on how Tiny Reparations Books will perform, but in my eyes, it's already a success. I have eight authors on the slate. All of them are first-timers. I guess my experience shopping around You Can't Touch My Hair really stuck with me, and I never wanted anyone to experience the amount of ignorance, disinterest, and lack of faith in their talent as I had. So it is my honor to be in the trenches with them, and my only hope is that every promise made by publishing houses during the summer of 2020 and the viral #PublishingPaidMe conversation is delivered upon. It's not up to me nor any of the brilliant writers on my slate to do the long overdue work publishing needs to do to be more inclusive, to pay writers from marginalized communities better, to nurture and hire more women, POCs, and queer people in gatekeeper positions. We're watching you, publishing industry, because we love you — and we know you can do better.

https://ew.com/books/phoebe-robinson-essay-fall-books-special/

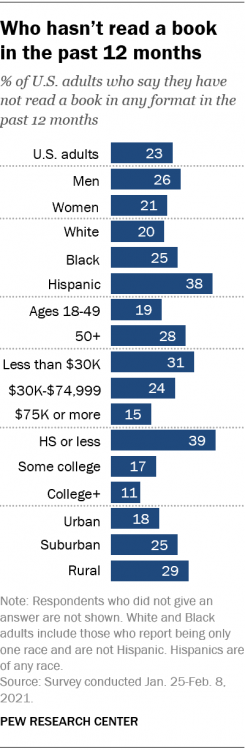

Who doesn’t read books in America?

BY RISA GELLES-WATNICK AND ANDREW PERRINRoughly a quarter of American adults (23%) say they haven’t read a book in whole or in part in the past year, whether in print, electronic or audio form, according to a Pew Research Center survey of U.S. adults conducted Jan. 25-Feb. 8, 2021. Who are these non-book readers?

Several demographic traits are linked with not reading books, according to the survey. For instance, adults with a high school diploma or less are far more likely than those with a bachelor’s or advanced degree to report not reading books in any format in the past year (39% vs. 11%). Adults with lower levels of educational attainment are also among the least likely to own smartphones < http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/ > , an increasingly common way for adults to read e-books.

In addition, adults whose annual household income is less than $30,000 are more likely than those living in households earning $75,000 or more a year to be non-book readers (31% vs. 15%). Hispanic adults (38%) are more likely than Black (25%) or White adults (20%) to report not having read a book in the past 12 months. (The survey included Asian Americans but did not have sufficient sample size to do statistical analysis of this group.)

Although the differences are less pronounced, non-book readers also vary by age and community type. Americans ages 50 and older, for example, are more likely than their younger counterparts to be non-book readers. There is not a statistically significant difference by gender.

The share of Americans who report not reading any books in the past 12 months has fluctuated over the years the Center has studied it. The 23% of adults who currently say they have not read any books in the past year is identical to the share who said this in 2014.

The same demographic traits that characterize non-book readers also often apply to those who have never been to a library. In a 2016 survey < http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/09/09/a-portrait-of-those-who-have-never-been-to-libraries/>, the Center found that Hispanic adults, older adults, those living in households earning less than $30,000 and those who have a high school diploma or did not graduate from high school were among the most likely to report in that survey they had never been to a public library.

Note: Here are the questions, responses and methodology used for this analysis < https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Non-Book-Readers-2021-Methodology-Topline.pdf >. This is an update of a post by Andrew Perrin originally published Nov. 23, 2016.

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/09/21/who-doesnt-read-books-in-america/

Inside the rise of influencer publishing

Many bestsellers of the last few years originated outside “traditional” publishing houses. But are influencers good for books?By Ellen Peirson-Hagger

We live in a world where everyone is a brand,” said Laura McNeill, a literary agent at Gleam Titles, which was set up by Abigail Bergstrom in 2016 as the literary arm of the influencer management and marketing company Gleam. Many of the UK’s biggest selling books of the last few years, from feminist illustrator Florence Given’s Women Don’t Owe You Pretty to Instagram cleaning phenomenon Mrs Hinch’s Hinch Yourself Happy, have been developed at the agency, and then sold for huge sums to traditional publishing houses.

Celebrity autobiographies and commercial non-fiction have existed for a long time. Gleam Titles’ modus operandi is more specific: it has a focus < https://www.gleamfutures.com/gleamtitles > on “writers who are using social media and the online space to share their content in a creative and effective way”. The term “author”, for the clients with which McNeill and her colleagues work, may be just one part of a multi-hyphen career that also includes “Instagrammer”, “podcaster” or “business founder”. These authors – whose books will become part of their brands – therefore require a different kind of management to traditional literary writers. “I do think the move to having talent agencies with in-house literary departments comes from these sorts of talents being a bit more demanding,” McNeill said. “I don’t want to come across as if those clients are difficult. But they are different.”

The biggest draw for publishers bidding for books by influencers is that they have committed audiences ready and waiting. Gleam understands the importance of these figures: on its website, it lists authors’ Instagram and Twitter followings beneath their biographies < https://www.gleamfutures.com/scarlettcurtis-titles > . When publisher Fenella Bates acquired the rights for Hinch Yourself Happy in December 2018, she noted < https://www.thebookseller.com/news/mrs-hinch-signs-mj-after-11-way-auction-917271 > Sophie Hinchcliffe’s impressively quick rise on Instagram, having grown her following from 1,000 to 1.4 million in just six months. Upon publication in April 2019, the book sold 160,302 copies in three days < https://www.thebookseller.com/news/mj-signs-second-book-mrs-hinch-1068146 > , becoming the second fastest-selling non-fiction title in the UK (after the “slimming” recipe book Pinch of Nom).

Anyone who has harnessed such an audience to sell products, promote a campaign, or otherwise cultivate a successful personal brand is an exceptionally desirable candidate to a publisher that wants to sell books. What’s more, the mechanics of social media means the size of these audiences is easily measurable, making the authors “cast-iron propositions” for publishers, said Caroline Sanderson, the associate editor of the trade magazine the Bookseller, who has noticed a huge increase in the number of books written by social media stars over the last couple of years.

A spokesperson for Octopus Books, which published Florence Given’s Women Don’t Owe You Pretty in June 2020, suggested that a book deal can raise an influencer’s profile too. When the book was acquired, Given had approximately 100,000 followers on Instagram. “Her book was acquired because she was an exceptional writer, not because she was an influencer,” they said. “By the time it was announced, she had 150,000 followers and when the book was published her audience had jumped to circa 350,000 followers. As the book and its message grew, so did her audience.” Women Don’t Owe You Pretty has spent 26 weeks in the Sunday Times bestseller charts according to data from Nielsen BookScan, and, as of August 2021, has sold over 200,000 copies.

Such authors also bring skills that a traditional novelist, for example, would not be expected to have. “These people are incredibly good at marketing themselves”, McNeill said, “which puts a lot of the work from the marketing and publicity departments of publishing houses onto the clients themselves.” In her previous role as an agent at Peters Fraser and Dunlop, a literary and talent agency that was established in 1924, McNeill sold books by Chidera Eggerue, also known as “the Slumflower”, and by “Chicken Connoisseur” Elijah Quashie, best known for his Youtube show The Pengest Munch. During the process, McNeill realised she was working with a new type of author: Eggerue and Quashie “wanted to talk about the branding and the image and the 360-element of it a lot more than any other writers I’d worked with before,” she said.

Some may feel inherently suspicious of the authenticity of anyone who makes a career out of social media, a pursuit often deemed trivial or shallow. Such suspicions – which often appears as disdain, or even ridicule – are prevalent in the publishing industry regarding books written by influencers, McNeill said. She told me she has observed a “snobbishness” about the books she works on, “from industry insiders way more than from the public”. One criticism often levelled against influencer authors is that they use ghostwriters. “There’s a misconception that none of these people write their own books, but plenty of them do,” McNeill said. “They’re creative talents and perfectly capable, but they might just need a bit more hand-holding and editing.”

When Quadrille published What a Time To Be Alone: The Slumflower’s Guide To Why You’re Already Enough in July 2018, it sold 1,961 copies in its first week, according to Nielsen BookScan. That should have placed it fourth on the Sunday Times general hardbacks bestseller list the following week, but “they just picked it out”, McNeill claimed, and put it in the “manuals” list instead, because its subtitle used the word “guide”. To her, this demostrates the industry’s unwillingness to understand the nature of the book, and to accept its significant audience.

The continued popularity of books such as Sally Rooney’s Normal People and Charlie Mackesey’s The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and the Horse, as well as hugely successful titles published in the last 18 months, such as Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror and the Light, have been credited with buoying the publishing industry during the pandemic. It makes sense that best-selling titles of any genre are helpful for the industry as a whole, as they get people excited about reading and into bookshops. But Kit Caless, co-founder of the independent London publisher Influx Press, called “the Reaganomic idea of a trickle-down system” a “fallacy”. The suggestion that a highly commercial book, such as Stacey Solomon’s Tap to Tidy, which spent ten weeks in the Sunday Times bestseller list, could be a “gateway drug” into reading is “patronising” and “tokenistic”, he said. “If they’re having to use Stacey Solomon as a Trojan horse to get people to read, I think that’s a failure on behalf of publishers to engage those readers in the first place.”

For the Bookseller’s Caroline Sanderson, it’s exciting that books still hold value among people who have found their success in the digital age. “I always think it’s amazing when people have built a platform on Twitter or Instagram, or increasingly TikTok, and the thing that they most want to do is a book, that it’s still the ultimate medium,” she said. She thinks the trend signifies “a real vote of confidence in what books are and what they can do and who they can reach”.

Sanderson said she has heard instances of people who, excited to read a book after seeing it advertised on social media, have asked “Where can I buy that?”, because they’ve never considered purchasing a book before. “It shows that there are people out there who don’t buy books but might. For me, that’s a holy grail. If they buy one book, they might buy another.” Though, she accepts, because the commercial non-fiction market is composed of a lot of “non-traditional” book-buyers, the likelihood is that they will buy online, often via am*zon. “The extent to which they benefit our highstreet bookshops is a concern.”

McNeill said that what she finds most exciting about the authors she works with – who are increasingly professionals who use social media to share their expertise, such as the astrophysicist Becky Smethurst, known on YouTube as “Dr Becky” – is that she’s breaking new ground, working with writers who wouldn’t necessarily have been given a chance to write a book for a mainstream publisher before. “I do think there is not enough risk-taking in publishing,” she said.

Caless agrees that mainstream publishing is too cautious, but considers Gleam part of that mainstream. Publishing a book by someone who already has a sizeable social media following is inherently risk-free, he said. While smaller publishers like Influx might “have an innate desire to take risks,” he said, “most publishers will publish books because they think they’ll make money; not because they think they’re good or healthy for culture.”

McNeill believes her books do both. “I’m excited by people who are able to communicate their expertise to a wider audience,” she said of Dr Becky, whose second book, an accessible exploration of black holes, will be published by Macmillan in 2022. And, time and time again, such an attitude has also proved to be immensely profitable. “These books had to fight for their place in the market. But now no one’s able to close their eyes to the phenomenon of how well these people are able to sell and communicate to their audiences.”

https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/books/2021/09/inside-the-rise-of-influencer-publishing

REFERRAL - Influencer Authors, Library eBooks, and a Ramona Quimby Walking Tour: This Week in Book News

https://kobowritinglife.com/2021/09/24/influencer-authors-library-ebooks-and-a-ramona-quimby-walking-tour-this-week-in-book-news/C. S. Lewis review of the Hobbit

C. S. Lewis Reviews The Hobbit, 1937

By C.S. Lewis November 19, 2013A world for children: J. R. R. Tolkien,

The Hobbit: or There and Back Again

(London: Allen and Unwin, 1937)

The publishers claim that The Hobbit, though very unlike Alice, resembles it in being the work of a professor at play. A more important truth is that both belong to a very small class of books which have nothing in common save that each admits us to a world of its own—a world that seems to have been going on long before we stumbled into it but which, once found by the right reader, becomes indispensable to him. Its place is with Alice, Flatland, Phantastes, The Wind in the Willows. [1]

To define the world of The Hobbit is, of course, impossible, because it is new. You cannot anticipate it before you go there, as you cannot forget it once you have gone. The author’s admirable illustrations and maps of Mirkwood and Goblingate and Esgaroth give one an inkling—and so do the names of the dwarf and dragon that catch our eyes as we first ruffle the pages. But there are dwarfs and dwarfs, and no common recipe for children’s stories will give you creatures so rooted in their own soil and history as those of Professor Tolkien—who obviously knows much more about them than he needs for this tale. Still less will the common recipe prepare us for the curious shift from the matter-of-fact beginnings of his story (“hobbits are small people, smaller than dwarfs—and they have no beards—but very much larger than Lilliputians”) [2] to the saga-like tone of the later chapters (“It is in my mind to ask what share of their inheritance you would have paid to our kindred had you found the hoard unguarded and us slain”). [3] You must read for yourself to find out how inevitable the change is and how it keeps pace with the hero’s journey. Though all is marvellous, nothing is arbitrary: all the inhabitants of Wilderland seem to have the same unquestionable right to their existence as those of our own world, though the fortunate child who meets them will have no notion—and his unlearned elders not much more—of the deep sources in our blood and tradition from which they spring.

For it must be understood that this is a children’s book only in the sense that the first of many readings can be undertaken in the nursery. Alice is read gravely by children and with laughter by grown ups; The Hobbit, on the other hand, will be funnier to its youngest readers, and only years later, at a tenth or a twentieth reading, will they begin to realise what deft scholarship and profound reflection have gone to make everything in it so ripe, so friendly, and in its own way so true. Prediction is dangerous: but The Hobbit may well prove a classic.

Review published in the Times Literary Supplement (2 October 1937), 714.

1. Flatland (1884) is by Edwin A. Abbott, Phantastes by George MacDonald (1858).

2. The Hobbit: or There and Back Again (1937), chapter 1.

3. Ibid., chapter 15.

Image and Imagination: Essays and Reviews, by C. S. Lewis, edited by Walter Hooper. Copyright © 2013 C. S. Lewis Pte Ltd. Reprinted with the permission of Cambridge University Press.

This article originally appeared in the Times Literary Supplement. Click here to read it on the TLS site.

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2013/11/19/c-s-lewis-reviews-the-hobbit-1937/Referral Article

https://www.openculture.com/2013/11/c-s-lewis-reviews-the-hobbit-by-j-r-r-tolkien-in-1937.html

.thumb.jpg.afc88dfee9cd2927de0c440601caac13.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.ed52910791d00308abb8c218695bec88.jpg)