Book Excerpt – My Remarkable Journey: A Memoir

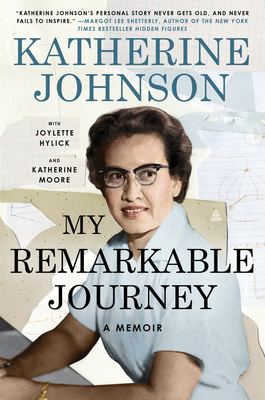

My Remarkable Journey: A Memoir

by Katherine Johnson, Joylette Hylick, and Katherine Moore

Publication Date: May 25, 2021

List Price: $25.99

Format: Hardcover, 256 pages

Classification: Nonfiction

ISBN13: 9780062897664

Imprint: Amistad

Publisher: HarperCollins

Parent Company: News Corp

Read a Description of My Remarkable Journey: A Memoir

Copyright © 2021 HarperCollins/Katherine Johnson, Joylette Hylick, and Katherine Moore No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher or author. The format of this excerpt has been modified for presentation here.

Chapter 1: Nobody Else Is Better Than You

The serious look in Daddy’s eyes told me his words were important:

“You’re as good as anyone in this town,” he said, peering down at my curious little face. “But you’re no better.”

I was probably in elementary school the first time I heard Daddy say that, and I’d most likely asked him one of my persistent “why” questions, namely why my white playmates, whose fathers worked on our farm, were allowed to call him by his first name. That always irked me because my parents had taught my two older brothers, sister, and me to address all adults as “Mr.” or “Mrs.” before their last name, as a show of respect. Daddy shrugged off the question, though, as just the way things were. What mattered, he stressed, was what I believed about myself: I was equal to anyone, no matter what the laws or traditions said.

I would hear some version of those words from Daddy repeatedly throughout my childhood, and they helped to shape me to the core. So even as I grew up and was told by law that I had to sit in the back of buses, climb to isolated theater balconies, and use colored water fountains and bathrooms because of my race, I chose to believe Daddy. I was just as good as anyone else, but no better.

Daddy always carried himself like he believed it, too. He was a tall, lean man who walked with a confidence that commanded respect. He wore Stetson hats, which he always tipped at ladies in the community. As a child, I always told my friends that my daddy was the “tallest, handsomest man in the world.” He had inherited his family’s farm in a small, country town about seven miles outside of White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. His father, who was of Native American descent, had left the farm to his children when he died. But Daddy’s four brothers and three sisters all moved away and left the farm in his care. The farm provided my father’s family the kind of independence that was rare for a colored family of that day. Such economic independence and good looks also made Joshua McKinley Coleman a desirable young bachelor in the days before he met my mother.

My mother, then Joylette Roberta Lowe, had been born in Ruffin, North Carolina, but moved to Danville, Virginia, as a child with her family. Her father was a minister, but he died when she was very young. Afterward her mother, who was a talented seamstress, somehow managed to raise four children, including two additional sons and another daughter, on her own. Both girls eventually became teachers. My mother attended Ingleside Seminary in Burkeville, Virginia, which was built in 1892 to educate colored girls. The school had been financed by northern churches and in 1894 was certified as a teacher training institute to respond to the growing demand for teachers to work in schools springing up across southern Virginia for colored children. Girls as young as sixteen years old were graduating from the Institute as teachers. My mother was eighteen when she started teaching in Virginia. At some point she had a diphtheria vaccination that became infected and left her sickly and with a large, unappealing scar on her arm. Her family figured the pure air from the West Virginia mountains and its freshwater mineral springs would help her recover, and so the teenager moved temporarily with a cousin to White Sulphur Springs.

Located nearly two thousand feet high in the Allegheny Mountains, White Sulphur Springs offered a cooler climate in the summer months than the lower regions, and its natural spring waters were believed to have healing powers. You could smell the minerals when you got close enough to the springs—at least that’s what outsiders said. The smell was part of the natural air I breathed, so close to the springs or not, I never noticed a difference. As early as 1778, visitors began flocking to the city to sip or bathe in the springs. A palatial hotel and resort, called the Greenbrier, was developed around the springs, offering premier golf courses, multiple fine dining restaurants, mountain-view pools, and more. The Greenbrier became one of the world’s most popular vacation getaways for the wealthy, and with extensive renovations and expansion over the years, it remains so today. Covering thousands of acres—eleven thousand at present—the resort has counted among its guests twenty-seven US presidents, royalty, diplomats, business tycoons, and other high-society family members. For most of its existence, the resort was owned by the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railway Co., whose passenger trains carried elite private coaches that delivered Greenbrier guests right onto the property. The property also includes ninety-six guest and estate homes, and in more recent years has been used as a training facility for NFL teams, as a professional tennis training center, and even as a concert venue. Locals lived in the town that sprang up outside the resort, and many worked there as servants. But they could not attend any of the events. Daddy later would work at the Greenbrier as a bellman, and he also earned money transporting the resort’s monied, white guests around in a buggy pulled by his beautiful horses. So it was at the Greenbrier that the pretty, petite teenager who had come to White Sulphur Springs to heal caught the eye of the area’s most eligible bachelor.

She was soft-spoken and tiny, standing just five feet, two inches tall with an eighteen-inch waist, while his gregarious personality matched his tall stature. Their names even matched—Josh and Joy—and they became a couple, courting for a few years before marrying in 1909. She was twenty-two, and he was twenty-seven. She moved with him to the farm, and they lived in a log-cabin-style house in an area known as Dutch Run. My older brother, Horace, was born first in 1912, followed by three additional children: my sister, Margaret (close family members called her “Sister”), in 1914; Charlie in 1916; and me in 1918. I was too young to remember much about our farm life firsthand, but my brothers and sister always looked back on the time with joy. They played outdoors all day, romped through the open fields, and picked huckleberries. Our parents allowed each of them to have a chicken or other farm animal for a “pet,” and they helped to care for it.

Daddy raised pigs, cows, chickens, and geese and maintained a large apple orchard. He grew an array of vegetables and fruits, practically everything our family needed to eat off the land and earn a living. Meat was salted down and stored in a shed, or “meat house,” for preservation, and some fruits and vegetables were stored in pits underground. To provide minimal refrigeration in those pits, farmers cut large chunks of ice from frozen ponds and covered them with sawdust. Farming was physically demanding work, but Daddy was strong and smarter than anyone I knew. Mamà (pronounced with emphasis on the second syllable) took care of the chickens, cooked all of our meals, and used a process called “canning” to preserve certain meats, vegetables, and fruits in glass jars for long periods of storage. That was particularly important during the winter months, when ice and snowstorms shut down the roadways and froze everything in place throughout the Allegheny Mountains. At an early age, we children learned how to shell peas, shuck corn, and take the corn off the cob for storage to feed the animals. Our parents bought only a few items at the store, including sugar, coffee, salt, and pepper. But shortly after the United States entered World War I in August 1917, some of those goods, particularly sugar and coffee, suddenly were in short supply.

The bloody conflict had been raging overseas for three years by then, and America’s European allies (the United Kingdom, France, and Russia) were practically starving. The war had turned farm workers into soldiers, changed former farmlands into war zones, and greatly disrupted the import of supplies, including food, to the allied forces. When the United States joined the battle against German aggression, President Woodrow Wilson created the US Food Administration to manage the conservation, distribution, and transportation of food during wartime. He appointed then-businessman Herbert Hoover to lead the agency. As the “food czar,” Hoover appealed to Americans to reduce their consumption of meat, wheat, fats, and sugar so that there would be more food to send to soldiers. Posters were distributed throughout the country with a targeted message, “Food Will Win the War.” Hoover even implemented a system in which Americans abstained from certain foods on designated days—for example, “meatless Mondays” and “wheatless Wednesdays.” The success of the effort drastically increased food shipments to Europe and eventually helped to catapult Hoover into the White House as the nation’s thirty-first president.

Mamà recalled that the federal government implemented a mandatory draft of men into the US Army during the war under the Selective Service Act of 1917. President Wilson signed the measure into law in May of that year. There were three registrations for the draft, and the third one was on September 12, 1918, for men ages eighteen through forty-five. Daddy, then thirty-five, was required to register in the third group, but he qualified for a hardship provision under the law and was not enlisted. That section of the law exempted married registrants with a dependent spouse or dependent children who would be left with insufficient family income if the breadwinner were to be drafted. I had been born less than a month earlier, and Daddy was the sole breadwinner of our family with four children to feed. I’m sure my parents must have breathed easier after learning that my father would not be forced to go to war. Two months later, relief came for the entire nation when the war ended on November 11, 1918.

During wartime and beyond, the farmers in our community banded together to help one another, regardless of race, especially during the critical harvest season. They worked on one another’s farms, shared equipment, and even sat around the table together for meals in one another’s homes. In that way our farmers were a different breed of southerners. They understood and respected the hard work, patience, and sacrifice required to earn a living from the land, and they needed one another, all of which often trumped the rules of segregation. When I eventually moved to Virginia as an adult, I always stressed that I was born and raised in “West, by God, Virginia,” which we citizens say frequently to emphasize our pride. West Virginia was formed during the Civil War, when it seceded from Virginia to join the Union in its fight against slavery. So to many of the state’s African Americans, “West, by God, Virginia” takes on an even more special meaning.

In addition to farming, Daddy bred horses and owned a few of them. The two most beautiful ones were reserved as riding or carriage horses, used to pull our family’s surrey, a two-seater buggy with a fringed cover across the top. Somehow, all six of us piled into the vehicle to attend church in town on Sundays. In addition to the carriage horses, Daddy kept two workhorses to help plow the fields and haul timber. He was a skilled logger who cut trees from around the farm and used the workhorses to pull a wagon, loaded with timber, to a nearby sawmill. Despite his limited education, Daddy’s mind was quick with numbers—a gift I must have inherited from him. He could add, subtract, and do complicated math problems in his head. He also could look at a tree and instinctively know how many logs he could get from it.

The farm and Daddy’s side jobs provided well for our family, but as my brothers and sister reached school age, my parents began to recognize some of the drawbacks of life in the country. The only grade school in the area for colored children was in White Sulphur Springs, and making that seven-mile trip twice daily each day would be disruptive for a busy farmer. So, when I was about two years old, Daddy moved our family into town to make it easier for my older siblings to go to school.

Our new home was much larger and fancier than the old farmhouse, and Daddy had built it himself. The two-story white frame house sat at 30 Church Street, in the middle of a thriving colored community. Everybody called the new place “the Big House,” and it definitely lived up to the name. There were four rooms on the ground level, and upstairs featured a bathroom with the first indoor plumbing in the neighborhood. The four bedrooms also were upstairs, one for Sister and me, another for Horace and Charlie, our parents’ room, and the guest room. The ceilings were painted sky blue, like Daddy had seen at the Greenbrier. And like the old plantation houses, four columns stood across the front, and broad porches on the top and bottom levels extended the entire width of the house. I enjoyed sitting on the front porch in a rocking chair. Unlike at the farmhouse, we also had a telephone, which was a party line, managed by an operator and shared by several families. Back then, no one had to remember an area code and seven-digit number. Telephone numbers were simple, and I still remember ours: 2–2–8.

Daddy got his hair cut down the street at Crump’s Barbershop, which was across the street from Haywood’s Restaurant, the only place in town where families from the neighborhood could sit and enjoy a meal. We still attended St. James United Methodist Church, but now we were close enough to walk. The church itself was a plain redbrick building with hard, wooden benches inside and lamplight. Though we were Methodist, the denomination lines blurred a bit out of necessity. Our church and First Baptist Church, which also was just down the street from our house, each had a part-time pastor, and both preached just two Sundays a month. So to attend church every Sunday, most people in the community went to St. James on the even Sundays and to the Baptist church on the odd ones. In the summer, Vacation Bible School was combined, as well as the congregations’ summer picnic.

We had many good neighbors, which included for a time Daddy’s stepmother, whom we all called Granny. Daddy’s mother had died when he was nine years old, and so we never knew much about her. Granny lived down the street, next to Crump’s Barbershop, and she made the most beautiful pancakes. My brothers, sister, and I often walked down the street and told her we were hungry so she would make us a batch. In her backyard Daddy kept a small vegetable garden that kept our tables filled with fresh, wholesome food all year long. Though not a blood relative, Granny was our closest connection to Daddy’s side of the family. I never knew Daddy’s father or his grandfather, but my family would learn later that Daddy’s grandfather was a full-blooded Native American. We haven’t yet linked our roots to a particular tribe, but the history of Greenbrier County, where White Sulphur Springs is located, can be traced to the Shawnee and Cherokee peoples. Even the origin of city’s popular springs is tied to Native American folklore. The Shawnee tribe originally inhabited the forest near the springs, and according to legend, two young lovers slipped away from their elders to the valley to be alone one day. When their chief found them, he became enraged and shot two arrows. One killed the boy, and the other barely missed the girl but struck the ground. The springs supposedly began flowing from the pierced earth. The legend says the girl’s lover will be restored to life when the last drop of water is drunk from the springs.

On Mamà’s side of the family, her grandmother had been owned during slavery by the white man with whom she bore four boys and two girls. Though it is difficult to imagine today, Mamà said she and her siblings thought well of the former slavemaster, who also was their grandfather. They called him “Bruh” Abe. After slavery ended, Mamà’s grandfather quietly kept his colored family together on one side of town, apart from his white family on the other. He also paid for his colored children to attend Hampton Institute, which had been founded in 1868 to educate newly freed slaves. Despite the fond feelings Mamà held for her grandfather, she seemed a bit ashamed of her lineage. She never uttered a word about her grandparents until many years later, when I began digging for answers with my questions. I can only imagine the tortuous conflict that she and other direct descendants of slaveowners must have felt, knowing that their fathers and grandfathers, who afforded them a life typically better than other African descendants, also perpetuated the degradation of slavery.

I loved our Church Street community, but I tagged along with Daddy every chance I got to return to the country. He maintained the farm and often brought bushels of apples from his orchard and sat them on the back porch of the Big House. He enjoyed the woods, and we often found ourselves there, just wandering or picking berries for one of Mamà’s delicious pies. Daddy knew the names of every creeping, crawling thing in those bushes. On one of our excursions, when I was about four years old, I felt something warm and slippery underneath my feet and asked Daddy what it was. Before I could bend over to explore, I heard Daddy shout, “Be still! Don’t move!”

The next thing I heard was a loud rifle blast. Daddy had shot a snake from right under my feet. “A copperhead,” he said, picking up the remains with a stick. As I stood there, still in shock, he pointed out the markings that distinguished this one from other snakes. “They’re poisonous,” he said, sending the first shiver of fear throughout my body. Daddy had saved my life. I’d always been a “Daddy’s girl,” but that moment solidified our bond. He would forever walk even taller in my eyes.

I learned quickly, though, that I had to share him, and not just with my family. The entire community, colored and white, seemed to trust Josh Coleman. He knew practically everyone in town, in part because he had multiple side jobs. He began working as a bellman at the Greenbrier when we moved to town, and he at various times cleaned the local electric company, the bank, the Episcopal church, and the library. Also, he kept the vacation homes of some rich, white families who came to White Sulphur Springs in summer to escape the heat and humidity of their hometowns. Daddy kept their keys to come and go, as he needed to maintain their properties while they were away and to prepare for their return in spring and summer. Daddy mostly wore coveralls when he cleaned or worked in the garden, but for church on Sundays and business in town, his preferred attire was a suit and tie with high-top leather shoes. He may have been just a good, reliable servant to the white people who hired him, but Daddy knew his own worth. And he built a cocoon around his children, protecting us from the knowledge that in the outside world, particularly in places such as Mississippi, Louisiana, and Virginia, a colored man could be snatched from his family, dragged before a crowd of bloodthirsty whites, and tortured to death just for carrying himself with a bit too much confidence.

Daddy was well known throughout the community for another reason: he had the gift of healing. People had noticed his special way with horses and began bringing their own troubled animals to him. He could calm even the most agitated horse and cure obscure maladies in them. He was a self-taught veterinarian who treated everyone’s animals at no cost. Neighbors and friends began trusting him for their healing, too. I suspect Daddy’s special gift and the healing remedies he used were linked to his Native American heritage and traditions. This was an era when there were no doctor’s offices on every corner, particularly in neighborhoods where colored people lived, and so people often relied on home remedies handed down for generations. Or they turned to healers like Daddy. The word around town was, if you had something wrong, go to Josh Coleman and he would take care of it. That’s what our neighbors from across the street, Robert and Ruth Core, did one day with Mrs. Core’s nephew. The boy was visiting from out of town and needed help to stop stuttering, they explained. Daddy spent a few moments talking calmly to the boy, touched his throat, and then pronounced that he would be fine. The boy never stuttered again, according to the Cores, who shared the story with their twin daughters, Annette and Janette. The couple also told their daughters about the time Daddy healed an unusual growth on Mrs. Core’s forefinger. The growth looked like a large wart, but it wouldn’t go away. Mrs. Core marched across the street one day and explained the situation to Daddy. He quietly took her hand, rubbed his fingers gently across the wart several times, and mumbled something. “Go on home now,” he told her. “It will be okay in a couple of days.” Sure enough, Mrs. Core told her daughters, the wart disappeared, just as Daddy had said.

Those kinds of stories added a mythical lore to a man who was already bigger than life to me. But I would witness Daddy’s “healing hands” myself as an adult when on different occasions he removed a cluster of warts from my baby’s eye and my oldest child’s hands. Removing warts was his specialty, and his remedy was connected to the Farmer’s Almanac, which he read faithfully, and based on phases of the moon. Apparently the moon was right for such healing at only a certain time of the month. During that time, White Sulphur Springs residents, colored and white, would make their way to our house, form a line outside the door, and wait for Daddy’s touch.

As a child, I was just a little girl in awe of her daddy, and I beamed when friends and family told me I was just like him. I heard that often when it came to numbers. It was well known that I loved counting everything I saw, and I always pushed myself to go higher and higher. Math just made sense to me, and I caught on easily, even before I started school. I loved sitting with my older siblings when Mamà helped them with their homework. Sometimes I’d even come up with the answers before Charlie, who was two years older. One day, when I was about four years old, I slipped away from home. Mamà came outside to look for me, but I was not in the yard. She knew exactly where she’d find me, and there I was, sitting inside the school with my oldest brother.

I vividly remember our neighborhood school, which was initially a two-room building called White Sulphur Grade School. But while I was a student there, the school was rebuilt into a white, wooden, three-room building and renamed the Mary McLeod Bethune Grade School, in honor of the legendary educator and activist who dedicated her life to the advancement of our people. Born to former slaves, Mrs. Bethune was blessed to receive formal schooling and believed education was key to racial advancement. She began teaching in the 1890s and in 1904 established a private school, the Daytona Educational and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls. The school later merged with another institution to form what is today Bethune-Cookman University in Daytona, Florida. Mrs. Bethune became a powerful advocate for civil and women’s rights and later would establish the National Council of Negro Women. Her influence rippled throughout the nation, reaching even a West Virginia mountainside, where a tiny schoolhouse, named in her honor, dedicated itself to educating Negro children. Charlie’s classroom held a total of about twenty students in first through fourth grades. Horace and Margaret were in the other classroom, with about the same number of fifth through seventh graders.

One of the teachers was named Mrs. Rosa Leftwich, who taught the lower grades. She decided to visit Mamà at our home one day after I slipped away to join my older siblings at school. I was playing nearby as the two women talked, and Mrs. Leftwich began spelling her words to keep me from understanding what she was saying. Mamà gestured frantically with her hands to let the teacher know that was unnecessary. Then, eager to show the teacher what I could do, I burst into the conversation.

“You don’t have to spell around me because I can spell,” I said cheerfully. “Want to hear me read?”

I had just broken one of the cardinal rules of home training: stay out of adult conversations. But I was so proud of my reading abilities and so eager to show off what I knew that I couldn’t help myself. Mamà had taught me to read. My never-ending questions always exhausted her, and to keep my curious mind occupied, she had taught me the alphabet, their sounds, and how the sounds came together to make words. It was like a game to me, and I loved figuring out how to spell everything I saw almost as much as I loved counting. That summer, Mrs. Leftwich started a private kindergarten class in her home with me and a few other children, and I officially started school at four years old. When the Bethune school opened in the fall, I had just turned five and was starting first grade. But it didn’t take long for the teacher to discover that I needed more challenging work, and in the middle of the year, I was skipped to the second grade. That wouldn’t be the last time I skipped a grade. In the beginning of my fifth-grade year, the school was rebuilt, and a third teacher, Miss Lottie Leftwich, was added. To even the class load, the principal, Mr. Charles S. Arter, visited my class one day and asked if anyone in the fifth grade wanted to move to the sixth grade. Mr. Arter was living in our home as a boarder at the time. There were either no or very few hotels or apartments available to young colored teachers, particularly in small communities, so it was common throughout the South for them to stay with other colored families who had an extra room. As usual, I hopped right up. I always wanted to learn more, and I figured moving ahead to the sixth grade would give me that opportunity. My teacher agreed that I could do it, and just like that, I skipped fifth grade and became a sixth grader.

By the time I entered sixth grade, I had skipped a few grades and was much younger than my classmates. I never thought of myself as advanced, no matter how much of a fuss other people made of me at church and in the community. I always wanted my classmates to know what I knew and was eager to share information. I don’t recall ever being scared or intimidated that they were older, and I never doubted that I could keep up. I may have been younger than everybody else, but even then, I knew for sure that I was just as good.