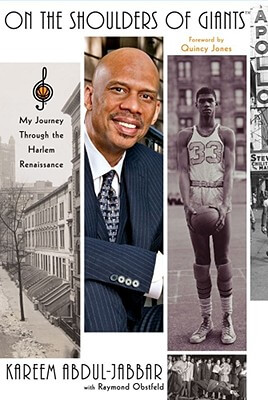

Book Excerpt – On The Shoulders Of Giants: My Journey Through The Harlem Renaissance

On The Shoulders Of Giants: My Journey Through The Harlem Renaissance

by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

Publication Date: Jan 30, 2007

List Price: $26.00

Format: Hardcover, 288 pages

Classification: Nonfiction

ISBN13: 9781416534884

Imprint: Simon & Schuster

Publisher: Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Parent Company: KKR & Co. Inc.

Read a Description of On The Shoulders Of Giants: My Journey Through The Harlem Renaissance

Copyright © 2007 Simon & Schuster, Inc./Kareem Abdul-Jabbar No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher or author. The format of this excerpt has been modified for presentation here.

"Some Technicolor Bazaar" How Harlem Became the Center of the Universe

Harlem!…Its brutality, gang rowdyism, promiscuous thickness. Its hot desires. But, oh, the rich blood-red color of it! The warm accent of its composite voice, the fruitiness of its laughter, the trailing rhythm of its "blues" and the improvised surprises of its jazz. ’poet and novelist Claude McKay It’s Harlem — and anything goes. Harlem, the new playground of New York! Harlem — the colored city in the greatest metropolis of the white man! Harlem — the capital of miscegenation! Harlem — the gay musical, the Parisian home of vice! ’author Edward Doherty I’d rather be a lamppost in Harlem than governor of Georgia. ’folk saying

When Black Was in Vogue

Once upon a time there was an enchanted land called…Harlem.

Considering all the transcendent things that have been said about the Harlem of the twenties and thirties, it would be easy to romanticize the place as an elaborate set of a movie musical-comedy extravaganza, filled with bubbly jazz melodies and populated by a happy cast of all-singing, all-dancing cockeyed optimists. But to do so would simplify the complexities of the history-making, life-and-death struggle that was really going on in Harlem. And it would reduce the residents to convenient one-dimensional stereotypes — the same indignities that the Harlem Renaissance fought so hard to erase.

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, Harlem has been considered the unofficial capital of an unofficial country: Black America. Because of that, in the minds of most white Americans, Harlem has symbolized all African-Americans — educated or illiterate, urban or rural, cop or criminal. One size fits all.

And that is the problem that Harlem, as a symbol of Black America, has faced from the beginning: there have always been two Harlems.

First, there was the idealized Harlem that white people imagined because of its portrayal in white films and in white literature. In the beginning of the Jazz Age, whites concocted "Oz" Harlem, the Technicolor home of sassy black women and musically inclined black men, eager to burst into song or dance at any opportunity. Sure, times were tough and they had plenty of nothin’, but, hey, by their own admission (or at least by the admission of black characters created by white writers), nothin’ was plenty for them. Whites admired how Harlemites had learned to accept their miserable lot in life with a Christian smile and without pointing any angry fingers of blame. "We could all learn a lesson in humility from them," whites said approvingly. In Oz Harlem, white folk were welcome, particularly in high-class nightclubs such as the Cotton Club, which featured black jazz performers, black dancing girls, and a deferential black staff — but allowed only white patrons. In Oz Harlem, blacks entertained and served, but didn’t mingle with whites. Oz Harlem was a white fantasy of perfect race relations, a racist’s Disneyland ("the honkiest place on earth"). And thousands of whites visited this Harlem weekly, seeing only what they wanted to see. Like people visiting a zoo who marvel at the animals but ignore the cages.

But behind the velvet curtain of Oz Harlem was the other Harlem — "Daily" Harlem — the one that black people wrote about, sang about, painted and sculpted. The one where black people actually lived, worked, cooked, went to church, gossiped about neighbors, and buried loved ones. This was the Harlem where they raised families, raised rent, and, on occasion, raised the roof. During the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s, those two Harlems — Oz Harlem and Daily Harlem — came to represent the two different ways all African-Americans throughout the country were viewed, not just by whites, but by other blacks as well.

In the end, these two radically different visions couldn’t peacefully coexist. For those who were part of the Harlem Renaissance, white America’s romanticized ideal of happy black folk singing away their worries and cares only encouraged the poverty and injustice to flourish. It allowed the real problems to be ignored. Especially by white politicians who had the power to change things. Ignoring Harlem, and African-Americans throughout the country, was business as usual for most politicians. As police detective Coffin Ed Johnson says in the film Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970), "What the hell do the attorney general, the State Department, or even the president of the United States know about one goddamn thing that’s going on up here in Harlem?"

But Harlem would not be ignored.

Jazz legend Miles Davis said, "Jazz is the big brother of revolution. Revolution follows it around." What was going on in Harlem in the 1920s and 1930s was nothing short of a cultural and political revolution. Certainly jazz provided the backbeat, but the revolution itself was orchestrated by a group of confident, educated, and talented young men and women undeterred by the perceptions and injustices of the past, their eyes firmly fixed on the prize: a future filled with limitless opportunities for blacks. And most of these cultural warriors would live and work and create, even if only for a short while, in Harlem.

How Harlem Got Its Black

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Harlem seemed an unlikely location for a capital of Black America — or the Mecca of anybody but moneyed whites. Located just north of Central Park, Harlem was where upper-middle-class whites resided in fancy apartments and magnificent brownstone houses. If you wanted to find the majority of New York City’s black population, you’d have to travel south of Central Park to the West Side, particularly to an area called the Tenderloin. This was where most of the city’s sixty thousand African-Americans were crammed. And living around them, like an army laying siege to a castle, were various groups of whites, mostly Irish immigrants, dedicated to driving the blacks away.

Central Park was a physical border beyond which blacks were not welcome; but money was the practical barrier keeping blacks from living in upscale Harlem. Without equal education or job opportunities, movin’ on up to Harlem didn’t seem possible. Yet, we know it happened, or this book would be about the Tenderloin Renaissance. But how? Ironically, it was Harlem’s desirability among the well-off whites that eventually resulted in Harlem’s evolving from ritzy white enclave to the destination for blacks from all over the country, and even from outside the country.

The section of the Tenderloin between Twenty-seventh Street and Fifty-third Street was called Black Bohemia. Black Bohemia sounds almost cheerful, like a lively jazz club or a tropical Jamaican resort. But, in fact, it was a squalid ghetto where black families strove to raise their children amidst brothels, gambling dens, nightclubs, pool halls, and unbearable poverty. In 1911, the average black laborer earned $28 a month; the average rent for a small four-room apartment in Black Bohemia was $20 a month ($2 to $5 more per month than in white neighborhoods). That left only $8 a month to survive. In 1900, Harper’s Weekly condemned the housing situation:

Property is not rented to negroes in New York until white people will no longer have it. Then the rents are put up from thirty to fifty per cent, and negroes are permitted to take a street or sometimes a neighborhood. There are really not many negro sections, and all that exist are fearfully crowded…. Moreover, [the landlords] make no repairs, and the property usually goes to rack and ruin…. As a rule…negroes in New York are not beholden to property owners for anything except discomfort and extortion. The rents weren’t the most serious problem. Hostility toward blacks reached explosive proportions in August of 1900 during the Tenderloin riots. The spark that lit the fuse occurred on August 12, on Forty-first Street and Eighth Avenue when a white undercover police officer dressed as a civilian attempted to arrest a black woman whom he thought was a prostitute soliciting. When the husband, not knowing the man was a police officer, attempted to defend his wife, the officer clubbed him. The husband then stabbed the officer with a penknife, killing him. Though the husband, because of the circumstances, was exonerated a couple days after the stabbing, police and white gangs roamed black neighborhoods in the Tenderloin looking for vengeance. Innocent pedestrians who ran to the police for protection were shoved into the crowd of rioters by angry officers. Frank Moss, who compiled the affidavits of black victims, said in his account, The Story of a Riot:

The unanimous testimony of the newspaper reports was that the mob could have been broken and destroyed immediately and with little difficulty…[but that] policemen stood by and made no effort to protect the Negroes who were assailed. They ran with the crowds in pursuit of their prey; they took defenseless men who ran to them for protection and threw them to the rioters, and in many cases they beat and clubbed men and women more brutally than the mob did. An official investigation not only cleared the police of wrongdoing, but praised them for keeping the situation under control. Yet, "the situation" was anything but under control for black residents, who lived under the constant threat of violence. Realizing that geography was destiny, the residents of Black Bohemia began looking around for someplace else to live — someplace where their children would have a better life than they did. As one Tenderloin resident observed, "Every day was moving day."

Harlem, by contrast, has heaven. White heaven. Thick, healthy trees lined the wide streets and avenues, which were newly paved and bracketed by luxurious apartments and houses. In a way, this was the paradise that public transportation had built. Named Nieuw Haarlem (New Harlem) in 1658 by the Dutch…