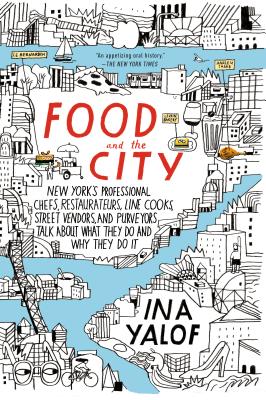

Book Excerpt – Food and the City

Food and the City

by Ina Yalof

Publication Date: May 07, 2019

List Price: $16.00

Format: Paperback, 384 pages

Classification: Nonfiction

ISBN13: 9780425279052

Imprint: G.P. Putnam’s Sons

Publisher: Penguin Random House

Parent Company: Bertelsmann

Read a Description of Food and the City

Copyright © 2019 Penguin Random House/Ina Yalof No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher or author. The format of this excerpt has been modified for presentation here.

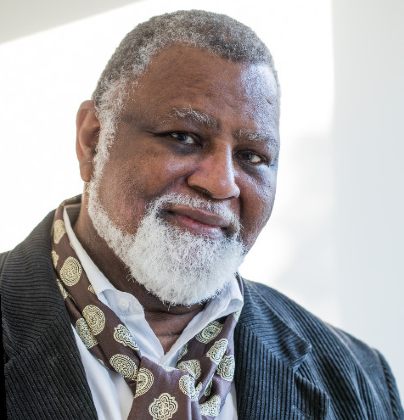

Alexander SmallsThe Cecil

Daylight floods his Harlem apartment, an eclectic space crammed with old and new mementos from a well-traveled, well-lived life. There are treasures everywhere, but I can’t stop looking at the walls of a narrow gallery that spans the three front rooms.

(This photo of Alexander Smalls is not included in book.)They’re lined from floor to ceiling with photographs of family members representing multiple generations, and of friends, famous and not so famous—singers, musicians, writers, and poets. His name belies his stature. He is tall and hefty, with a buoyant personality as large as his physique. His deep, rich, baritone voice is well suited to a gifted raconteur, which he is, and to an opera singer, which he was. His storytelling, Smalls believes, is in his genes, passed down from his grandparents. “They leased land for livestock and would take me with them to the slaughterhouse when I was young. We’d bring back the meat to their house and spend the afternoon in the kitchen making sausages. And while we were doing that, they would tell me stories. This oral history is how my siblings and I understood where we came from. Nobody was interested in writing about who we were, and oftentimes, who could write?”

(This photo of Alexander Smalls is not included in book.)They’re lined from floor to ceiling with photographs of family members representing multiple generations, and of friends, famous and not so famous—singers, musicians, writers, and poets. His name belies his stature. He is tall and hefty, with a buoyant personality as large as his physique. His deep, rich, baritone voice is well suited to a gifted raconteur, which he is, and to an opera singer, which he was. His storytelling, Smalls believes, is in his genes, passed down from his grandparents. “They leased land for livestock and would take me with them to the slaughterhouse when I was young. We’d bring back the meat to their house and spend the afternoon in the kitchen making sausages. And while we were doing that, they would tell me stories. This oral history is how my siblings and I understood where we came from. Nobody was interested in writing about who we were, and oftentimes, who could write?”

***

My grandparents were the children of slaves. I grew up in the South, in an area known as the Low Country. Low Country spans across Charleston, Beaufort and Savannah, a region heavily influenced by West Africa. When the African slaves came to America, they largely came to places like Charleston, which, aside from New York, had the largest slave market in the country. A lot of my heritage, the stories and the rituals of West Africa, came along with those migrating blacks.

The dawning of Sunday was ritualistic in my home. We woke up early and dressed for church, and my mother would start her preparation for Sunday dinner, the absolute best eating ever. It didn’t matter what you had during the week. Come Sunday, you could always expect a feast. If it was summertime, we ate on the side porch, under the shade of big oak trees. My mother made a panful of hot buttermilk biscuits with fresh butter and sorghum. Potato and macaroni salads, fresh creamed corn, fried okra, and some kind of roast followed that. If we were lucky, we could get some dumplings out of the deal as well. Of course no one used the expression then, but ours was definitely a farm-to-table home. Our extended family lived on a triangle of connecting lots. My grandfather lived at one point. Uncle Jo lived at the second, and we lived at the third. A path connected these houses, and if I was clever enough—and fast enough—I could time it where I would have two breakfasts, two lunches, and two dinners. Needless to say, no grass could ever grow along that path. As a kid, I had an enormous gift for music. When that gift became obvious, my aunt and uncle took me in hand and guided my musical education with laserlike attention paid to who I was and who I would become. My mother had her own ideas, but on one thing they all agreed: I was not going to suffer the rough roads, the misguidance, and the difficult bumps that are prescription for a number of African American males growing up, particularly in the South. So music became the foundation of my expression. As I learned to play the piano, I developed as a vocalist as well. I was only eight years old when my uncle introduced me to opera. I got hooked on Joan Sutherland and Marilyn Horne doing duets on Ed Sullivan, and afterward, I would literally stand in front of my mirror and imitate the singers. If it was a male and female duo, I’d throw a shirt on my head to be the female and I would sing in my high voice, and then throw it off and sing like the man.

As time went on, I spent more and more of my time in voice training, eventually ending up at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, one of the best music schools in the country, if not the world. When I started winning competitions, my fate was sealed. I set out to be the first major African American male opera star, a privilege that had been denied up to that point. African American women were considered exotic, so there was always a place for them after Marian Anderson broke those barriers. But the African American male? Not yet there.

When I was in Philadelphia, the Houston Grand Opera gave a performance of Porgy and Bess at Philharmonic Hall. I auditioned and was hired for the chorus. I traveled with that production throughout the States and in Europe, and when it was over, I stayed abroad. While singing and studying in Europe, I was also cooking my ass off. All of my performing friends flocked to my house for Sunday dinner until one day I realized that entertaining them was becoming more important to me than my music; in fact, my singing jobs in Europe were petering out. That’s when I decided to come home.

Here, suddenly, everything I had done abroad careerwise meant nothing. I was in my late twenties by then and I had to audition all over again for every role. It was like starting from scratch. And a rude awakening. My skin color was a big problem. There were no African American male superstars in opera. When I was in Porgy and Bess, I remember looking at all of these middle-aged men of color, some with grandchildren, who were still saying, “When I make it.” I was, like, “Don’t let me be this person who doesn’t realize that his time has passed.” When the last audition I did turned out to be for a very minor role, I went back to my apartment, had a big glass of red wine, and decided I was done. I couldn’t afford to have other people decide my fate or what my legacy would be. From that moment on, I would own my own stage, even if it meant selling hot dogs in Central Park. It was the most sobering moment of my life. Because cooking and entertaining are so important to me, it seemed only natural that this would be my new career path. I was living in a large loft downtown and entertaining small and large groups all the time. Soon enough it dawned on me that I’m doing again just what I did in Europe. I not only needed to get these people out of my house, but it was high time someone else bought my dinner for a change. And that’s when I opened my first restaurant, Café Beulah.

Talk about naïve. I don’t know what I was thinking! The only thing I knew about the restaurant business was what I had learned as a singing waiter one summer in Tanglewood. I knew nothing! I wrote a semblance of a business plan, went out and tried to raise money. Fortunately, I had a lot of friends in high places, and in an excellent show of confidence, they were all happy to help. I went to Percy Sutton, who used to own the radio station WBLS as well as the Apollo Theater and is regarded as one of the deans of the African American evolution in Harlem. I went to Toni Morrison, the writer, a good friend who loved my food and came often to my New York soirées. I went to my friend Kathleen Battle, the opera singer, who also was happy to help.

We hit the ground running. From the moment we opened the doors in 1994, Café Beulah was a success. The timing could not have been more perfect. People were discovering that restaurants were more than just a place for a great meal. There was an entertainment factor built in. You found a new place and you reported it to the world either on the Internet or through Zagat’s, and so your diners became your PR department. I picked the perfect downtown location. And we had a wonderful menu that introduced New Yorkers to what I called “Southern revival cooking with Low Country notes.” It was the food of my childhood, a fusion of French Creole, African, and the Far East. We served a lot of seafood and game, but with a regional character all its own. Diners loved the food; that was never in question. And the place was always packed. In fact, everything was right on target—except for the fact that I had no idea how to run a restaurant. And I kept running out of money.

A big part of the problem was my role in the restaurant. I started out as the chef, but people ended up coming into the kitchen to hang out with me while I cooked. Well, you can imagine how that worked out. To socialize and broil a steak to a certain level at the same time is rarely well done (if something can be rare and well done at the same time). This is when I understood that I should be “the guy up front,” and let someone else do the cooking. But even that didn’t help. As busy and as popular as Beulah was, and despite some great reviews, in five years we ran out of money and had to close. There were so many reasons for our demise. For one, we had a difficult time turning tables, which meant that instead of two or three diners in a chair of an evening, we had one. People wouldn’t vacate their tables. Imagine if you have Julia Roberts at one table, and Catherine Deneuve sipping bourbon at the bar, Jane Fonda, Glenn Close, Debbie Allen, Jessye Norman, and Kathleen Battle sitting around you, would you want to leave? Literally, I had to go around and plead with them, “I need your table. I’ll buy you drinks at the bar.” But nobody listened to me. We closed in January 1997. I subsequently opened and closed two smaller restaurants, and that’s when I started traveling.

On my return from one of my trips, I got a call from Richard Parsons, a long-time pal who was the former CEO of Time Warner. Richard loved the restaurant business, particularly nightclubs. He had always wanted to own a jazz club, and we set about looking to make that happen. One day, while looking for real estate, I stumbled upon a building on the quiet corner of 118th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue in Harlem. The building had been the historic Cecil Hotel, but it was now Section 8 housing, otherwise known as single-room occupancy or SRO. Not exactly the environment most people would think to put a new and upscale restaurant in, but to me it was perfect. And in a dual stroke of luck, in that same building but around the corner, was a running jazz club called Minton’s. Minton’s is the home of bebop, the foundation of modern jazz. Monk, Dizzy, Bird, Charlie Christian, Hot Lips Page. All these guys performed there on a regular basis.

In 2009, Richard and I bought the space where the Cecil is now. In the process of developing it, Minton’s became available and we bought that too. It was thrilling for both of us to think we could bring this legendary jazz club back to its former glory. In its time, Minton’s had been the most elegant club in town, with white linens and everyone dressed up. We decided to continue that legacy by installing a house jazz band and pairing it with authentically American food that was reflective of the jazz image.

On the other hand, opening The Cecil allowed me to realize a dream I have always had. I had always wanted to learn about, celebrate, and recreate the food of the African diaspora. The “African diaspora” refers to the groups of people throughout the world that are descended from slaves who were taken from Africa and transported to distant places such as the Americas, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. To learn about the food they made, I traveled to the countries where they landed. Using Africa as my base, I followed the slave route to South America, Europe, Asia, and the Caribbean. In each place I discovered new foods that fused African roots with flavors and foodstuffs of the newly inhabited world.

I based The Cecil’s menu on what I learned from those trips. Many of the dishes fuse Afro/Asian/American culinary techniques and flavors. For example, a Brazilian feijoada, which is a traditional meat and bean stew, now includes lamb merguez and oxtail. In a nod to the Orient, we created a whole section of rice bowls with a choose-it-yourself protein, or a Chinese chicken sausage. Our specialty dish, which emulates the all-American Southern fried chicken, is actually a cinnamon-scented fried guinea hen, which we serve on top of a bed of charred okra. Other hybrid American dishes include benne-seed–crusted Skuna Bay salmon with scallion grits, corn, and house-made kimchi, and gumbo consisting of smoked chicken, Gulf shrimp, crabmeat. The ambience of the restaurant is meant to showcase the Diaspora as well. Masai wallpaper covers the walls, and a picture of an Afro-Asian geisha graces the rear wall. Even our music is influenced by the connection between Africa and the landed countries.

So much has gone into creating this moment. I wanted to say something authentic, honest, and inspiring about the tragedy of slavery and people uprooted; to show the other side of something so horrible that bears beauty. I am trying every day to do this through the culinary experience. It has been a gamble, no getting around that. But for me it has also been a gift that happens only once in ten gathered lifetimes. When you are so absolute in your conviction, you have very little time to debate or measure if people are going to get it. I was basing the success of this multimillion-dollar project on the fact that people would both understand and love what I do. The Cecil is no little venture. A lot has gone into making this huge statement on the corner of 118th and St. Nicholas. But I felt like, if I were allowed to explain my motivation and my passion, people would understand.

And if they didn’t? If they didn’t, and if I gave them something undeniably delicious that kept them coming in and back, then the hell with all the rest of it. That works for me, too.

Author’s note: The Cecil Restaurant closed it’s operation after 3 years and merged with Minton’s Jazz Bar - New York’s oldest Jazz Bar - next door in 2016. Today, known as Minton’s Playhouse, the venue serves up some of Harlem’s hottest jazz and food.