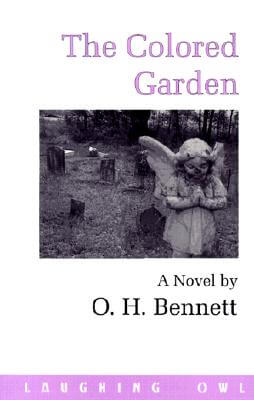

Book Excerpt: The Colored Garden

by O.H. Bennett

From Chapter One: Meeting the Gardener

In the middle of Kentucky farmland where a cornfield of withered brown stalks meets the grass of a cow pasture there is a tiny huddle of stones. They are surrounded by a knee-high picket fence and canopied by two old oaks just outside the weathered pickets, though one oak has not borne leaves for a few seasons and stands only out of stubbornness. The stones still stand too-straight, most of them-enduring the sculpting of rain and the whittling of wind. Here is a formation of good and loyal soldiers stiffly awaiting inspection. Here are ancient, spindly teeth, much gnashed, jutting up from green gums. Here is a quiet orchard of red-brown rock and chalky stone, whose messages of remembrance are only faintly visible.

Beneath the markers are the sleepers, neither fitful nor troubled. Most were strangers in life, but now have become a close and enduring family. They are connected and settled through decades of repose. They belong to that growing thing of the land that is black earth and searching roots and crawling life. They are part of the very land they once toiled upon for these are the souls of slaves and the souls of sons of slaves. They were buried at a time when the gates of heaven kept separate and unequal entrances. And there are more here than the stones will testify to; they were laid to rest without markers or their wooden crosses have long ago rotted away. But even those souls whose names are not etched anywhere on this earth have an unmistakable presence in this small corner of a cornfield. On summer days, years ago, I could see them, the vibrant, palpable spirits of long ago ancestors.

Today, I see them again, black skin made blacker by the sun, full Negro lips pressed together, wearing worn, ill-fitting clothes. They make little note of me, except to say, isn’t that the boy who many times came visiting with Ruth? So, perhaps my presence has served to heighten their anticipation for the one who has guarded them and tended them for decades. The whites of their eyes betray their anxiousness and they press near the fence to gaze down the narrow, dirt trail. They listen for the soft steps of their sister, Ruth Standard.

Something in me wants to avoid this confrontation; this is not a new feeling, but the desire to resist it is certainly new. The strong wind at my back prods me forward, goading me to leave, but when I step out onto the trail that leads gradually uphill to the barn, I stop and hold my ground even as my heart quickens. I resolve to wait with those whom I know best, stealing courage from them. My family won’t think to look for me here after all this time. This isn’t where I’m supposed to be. Kenneth Willis has made a career of that: being someplace else.

My suit and my tie would testify that I made an effort. I always try. On high school graduation day eight years ago, I tried to come here. I stood in cap and gown, proud of my accomplishment, though I numbered near the very bottom of the class of ’82. There was no one to cheer me on, except the new Mustang my father the Colonel had promised me, the carrot he had dangled at my nose for four years. An IG inspection had kept him away, he said. I honestly did not mind at all, relieved not to feel the pressure of his disappointed expectations.

By the time I arrived home from the auditorium, I had concocted an unexpected plan: I would leave. No good-byes, no questions, just go. I would drive up to Kentucky to see my grandmother Ruth. I packed haphazardly, leaving many things behind. I gave no thought to informing the Colonel. By that, I mean, I didn’t even think of it. I paused only in the living room, in front of his little two-stool bar, behind which he kept decanters and flasks of all sizes. But my release from school and the mechanical power of my new car had me feeling free and strong. I bypassed the row of bottles.

I hit the open highway feeling giddy with freedom. No more Colonel, no more teachers and counselors. I had a little graduation money for gas and food, and no one who knew me had any idea of my whereabouts. At first, I saw nothing but the road and its white painted dashes that fired like bullets at the front of my car. My radio rocked anthems to my freedom and my left hand tapped the beat on the car’s side. I left the windows down so I could feel and hear the rush.

I went for miles on that high, over the hills of northern Georgia. Somewhere along the stretch of a two-way road, I began to notice the countryside: dilapidated, weather-beaten barns, a rusting cultivator in the middle of a field, rows and rows of crops. All of this made me think of the Standard farm, and the first summer I lived there; without being conscious of it, I eased off the gas, the white bullets on the pavement elongating and coming at me more slowly. I realized I didn’t want to go where I was headed, and I didn’t want to turn back either. My car drifted to a stop, coughed and died in the middle of the highway. I couldn’t have sat there for more than a few seconds, but I’m not certain. I stared at the speedometer, but I thought of Mama, and Julie, and Gramma Ruth and her garden. I saw the car coming from the opposite direction, yet thought nothing of it. The blast from the semi-trailer’s horn behind me woke me up. He was charging up on me fast and the oncoming car prevented him from going around. I remember seeing the truck’s great, chrome grillwork, and have made myself believe I saw the shocked expression on the tractor driver’s face when he realized the car in front of him wasn’t moving. I turned and started my car, heard the hiss and growl of air brakes and the truck’s tread biting at the pavement. The horn blared right at the back of my head. I stomped on the gas pedal and pulled off the road just as the gusting wind of the passing trailer shook my car and slapped at my face. The driver still laid into his horn and its loud anger only faded with distance.

I fought to get control of my heart, and stayed for a long time on the shoulder of the road. When I finally continued my trip to the Standard farm that day I was much more sober, and I did not feel so much free as just alone. I made it to the farm that day, but not to here. Not to the cemetery. I make up for that day now.

The first day I came here was in late May or early June fifteen years ago. I met Mrs. Ruth Standard, my eccentric grandmother. I was an unhappy nine-year-old who’d just left his father in Germany and flown across the Atlantic, then bussed across half of the United States.

"It’s up to you to look after the women, Kenny," my father had charged me at the airport. He picked me up, stood me on a waiting room chair so that we were almost eye to eye. "That’s why I’m giving you a field promotion to Sergeant."

"Yes, sir. Thank you, Major."

"Oh, no, Daddy, he was hard enough to live with when he thought he was a corporal," Julie said.

"At ease," I told her. My father moved to hug me, but I gave him a trembling salute, wanting to cry but wanting to be a good soldier too. The Major came to attention smartly and returned my salute.

He hugged Julie, who began to cry immediately. Then he hugged my mother as Julie and I watched. Even at that age, I could tell from the hug alone-it wasn’t tight enough, it wasn’t long enough-that something was wrong. I knew life was changing for me, but not how or why. The flight over the ocean that I had convinced myself to look forward to was a bore. I had argued with Julie for a window seat only to see an unbroken floor of white clouds. The bus trip from the East Coast to the hills of Kentucky proved to be little better. Still, I hardly slept during the two-day journey. I was worried; the way little boys worry, becoming confused and ill tempered. Frequent glances at my mother’s face told me nothing. I wasn’t afraid to ask her what was going on, but I was afraid of the answer. I stayed quiet, kept my forehead pressed against the Greyhound’s cool window, and watched the cow barns and billboards fall away. Mama had a real hug for the big man who greeted us at the bus station. "This is your grandfather, kids."

"I know," Julie said and the old man kissed her on the cheek.

Timidly, I shook his hand. He had long fingers and dirty nails.

I climbed in the back of Grandpa Standard’s pick-up with the luggage and finally enjoyed a part of the trip. With warm wind blowing the smells of farms, wet fields and livestock into my face, the truck turned down one narrow road after another until we crossed an open field along a gravel trail and pulled into the Standards’ farmyard. Chickens scattered in front of the truck and a dirty-nosed collie crawled from underneath the porch of the Standards’ big house.

Julie jumped from the cab of the truck. "This is where you grew up, Mama?"

"The very place," Mama answered, following Julie out of the truck. She looked around for a long while and the man who was my grandfather smiled watching her. "The very place," she repeated. "Dad, where’s Mom?"

I remember thinking how strange it was to hear my mother call other people Dad and Mom.

Grandpa Standard scowled. "She’d be running full throttle out the house by now if she were there so you know where that leaves. Dang woman does it to aggravate me. Julie, run behind the barn, pick up a dirt trail and follow it on out to your Grandma. Fetch her back."

"Okay, Grandpa. Come on, Kenny." And then Julie said sweetly to the dog, "You can come too. What’s his name, Grandpa?"

"Don’t have no name. Fool dog just trotted in here a couple of weeks ago and made himself at home."

Julie and I raced to the barn calling the dirty-nosed dog and he followed after us. We found the trail down the hill from the barn. It ran between a field of corn, with stalks as tall as I, and a fence overgrown with vines and blackberry bushes. But the berries were small and green.

"Julie, are we going to live here?" I asked her. She said nothing and kept running.

When we came to a clearing where the rows of corn and the shaggy, green fence both turned away from the trail, only the dog kept running, bounding over a low, white fence and into a graveyard. Julie and I came to a complete stop. An old woman kneeled near one of the headstones, and I could hear the snip snip of fast-moving clippers. The dog ran in between and around the stones then stopped to smell one with concentrated interest.

"Zeke, don’t you dare." The woman threw something at the dog who took off running toward us. Her gaze followed him out of the cemetery and right to Julie and me. "Lord sake," she said, beckoning us. She pushed herself to her feet with the help of the nearby stone. "Well, come on. You can move faster than I can."

Julie stepped forward and I followed. "This is spooky weird," I whispered.

She hugged Julie and after a moment Julie hugged her back. Then the old woman, who was only old to the eyes of a nine-year-old, ran her fingers through Julie’s hair. "Such nice hair," she said. "You get that from our side of the family." Then she turned her attention on me.

Grandma Standard was an older version of my mother, though smaller. Her hair was dark, though on each side of her head, strands of white-gray were tucked behind the ears. "This is my Kenneth?" She smiled with the little wrinkles around her eyes. "You were a baby last time I saw you. Now you’re a-"

"A sergeant!" I told her.

Julie rolled her eyes. "Daddy promoted him."

"I see." She laughed. "Well, Sarge, will you give your Grandma a hug?"

I shook my head quickly. "Kenny!" Julie scolded.

"That’s all right, Julie. The Sarge here and I are strangers. After he gets to know me he might want to give me a hug. And after I get to know him, I might not want one." Julie and Grandma Standard laughed. And even though I was the butt of her joke, I laughed too. I stopped when I remembered where I was.

"Are you in mourning, Gramma?" Julie asked. "You’re not wearing black. Grandpa sent us to fetch you."

"Dogs fetch sticks," she said. "That’s about all the fetching that gets done around here." She picked up her basket of tools. "And there’s no mourning done in this cemetery. This is a garden of good souls at rest."

Flowers decorated the sides of most of the headstones and along the fence in orderly files as bright and rhythmic, with their heads bobbing in the wind, as a uniformed band. The grass grew low, green, and even. Some graves were outlined with rocks painted white. Many of the markers were uncut stone pointing at various angles at the sky. The true headstones were thin, chalky and rough edged, and their inscriptions were faint and fading. Two small crosses mingled in with the pack of stones and one small monument, newer and more ornate than the rest by far, had a stone baby with wings perched atop it. I read the stone nearest me. Hattie May Born 1790? Died April 20, 1863 "When the roll is called up yonder."

"Kenny, don’t stand on the grave. The ghost will haunt you!" Julie said.

I jumped quickly to the side and apologized to the stone.

"Hattie wouldn’t mind, Sarge." Grandma Standard told me. "Young boy like you, she’d put right in her lap and sing you a song."

Read Laughing Owl Pub Inc’s description of The Colored Garden.

Copyright © 2000 Laughing Owl Pub Inc/O.H. Bennett. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher or author. The format of this excerpt has been modified for presentation here.