Dear Verdel

by Ina Yalof

Dear Verdel,

It has been decades since you kept house for my family, but I still think of you every so often. Perhaps now more so than ever, as the Black Lives Matter movement has had such an impact on our current day culture. I live in New York City now, but still I have begun to consider what it must have been like to walk in your shoes back then. Particularly in a place such as where I grew up, land of sun and fun, Coppertone and coconuts, warm sand and salty waves. It was post card perfect our home town. We grew up in a cocoon: Beautiful, safe Miami Beach, Florida.

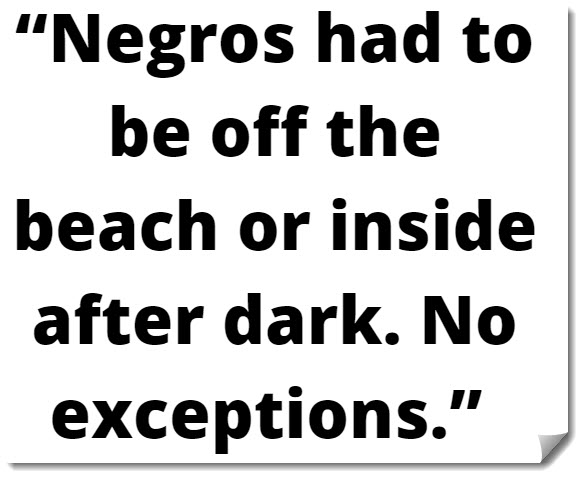

But Miami Beach in the Fifties was also a paradigm of segregation, even though as an adolescent I’m pretty sure I was unfamiliar with the word. In place were unspoken “laws” – were they ever truly laws? - that kept us “protected and secure.” From what, I never quite understood. One such law stated: “Negros (the term used in those days, and so I shall carry it through) had to be off the beach or inside after dark. No exceptions.” I’m guessing that’s why you rushed to finish the dinner dishes every night and ran out to catch your bus for a forty-five minute ride across the causeway to your home in Liberty City. Another decreed Negros could drink only from specified public water fountains, and use bathrooms whose doors were labeled “Colored.” I remember that even movie theaters in downtown Miami sequestered Negros in the balcony.

But Miami Beach in the Fifties was also a paradigm of segregation, even though as an adolescent I’m pretty sure I was unfamiliar with the word. In place were unspoken “laws” – were they ever truly laws? - that kept us “protected and secure.” From what, I never quite understood. One such law stated: “Negros (the term used in those days, and so I shall carry it through) had to be off the beach or inside after dark. No exceptions.” I’m guessing that’s why you rushed to finish the dinner dishes every night and ran out to catch your bus for a forty-five minute ride across the causeway to your home in Liberty City. Another decreed Negros could drink only from specified public water fountains, and use bathrooms whose doors were labeled “Colored.” I remember that even movie theaters in downtown Miami sequestered Negros in the balcony.

But it’s the bus rides in those days that I have never forgotten. Understood, but possibly undocumented tenets stated that Negros had to ride in the back of the bus or to stand, even though there might have been empty seats toward the front. I thought nothing of this, actually, because at the time I was 12 and that’s just the way things were. That is, I thought nothing of this until one evening, in early December, when my parents turned on the evening news as they always did just before dinner and my world view changed.

The year was 1955. President Eisenhower had just taken us out of the Korean war, our big national issues centered around the Cold War with Russia. But on December 1, what got my attention that night was a brief story about a diminutive 42 year old Negro woman named Rosa Parks. As the story went, a tired Mrs. Parks was returning home from her job at the Montgomery Fair department store in Montgomery, Alabama, when she hailed a bus and took a seat mid-way to the rear. At a subsequent stop, a white man got on and asked Mrs. Parks to move and give him the seat. She refused. And that simple act ultimately sparked a year-long bus strike by Montgomery Negros. This act of solidarity ultimately culminated in a change in the long held discriminatory rules of that state. Do you remember that, Verdell? You were young, too. Perhaps in your late twenties. I wonder now, were you as tired after a long day of cleaning and cooking for our family as Rosa Parks was from her job at the store? Did that monumental act of civil disobedience have any impact on you?

It did on me. I sensed that night that things were somehow not right. I want to believe I was color-blind before that, but maybe it was my way of denying what I knew all along. In any case, long before the strike was settled a year later, this twelve-year-old girl decided to try to do something to right what I saw that night as a clearly universal wrong. And so I promised myself that from then on, whenever I got onto a municipal bus, which was often in those days, I would sit in the back with the Negros. Since the word “solidarity” was not yet in my seventh grade vocabulary, let’s just say I thought I was doing something “nice.”

The problem was, just like Rosa Parks wasn’t welcome in the front of the bus, I was not welcome in the rear. The first time I edged my way to the back and took as seat, a kind, elderly woman quietly told me to please just move up front and not start any trouble. Which I did. Never to make the attempt again.

So I’m thinking about you now, Verdell. And I want you to know that whenever possible, I tag along with the Black Lives Matter groups. If I can march in commonality, I do. I do it for you. But more importantly, I do it for me and my Southern family and our inability – more like disinclination – at the time to raise our voices. Today, I can. It’s the least I can do.