There are two basic routes to getting published, mainstream and self-publishing. Mainstream is when one submits one’s work to journals/magazines and publishing companies to be published. Self-publishing is when one decides to publish one’s own books. They both can be equally effective although the mainstream manner is the most respected because it allows one to reach a larger audience more quickly and it has an aura or illusion of validation. Although self-publishing does not offer the validation from the establishment, it offers a satisfaction of artistic and economic control of one’s work. Yet, the most effective manner of publishing is to use various aspects of mainstream and self-publishing simultaneously.

Mainstream:

Again, the mainstream route is when one is hoping to obtain a book deal with an established publisher.

The cons of publishing using the mainstream route are:

- Most larger publishers do not accept unsolicited manuscripts from writers without an agent,

- The larger publishers usually require writers to surrender their rights to the material for some period of time, usually anywhere from two to five years,

- Even though one may have a deal with a major publisher, it is still required of that author to schedule readings and signings across the country, and

- Most first time authors earn only ten - fifteen percent of the profits of the book.

The pros of publishing using the mainstream route are:

- Because they are established (ingrained into the minds of the reading and buying public) there is an innate sense of acceptability and validation of the writer and the work and

- One has the mega-machine behind one, which allows one’s books to be placed in bookstores across the country as well as gain entrance into “so-considered” prestigious organizations and societies.

Most writers embrace the mainstream route because it frees them to be creative, or so they think. Although one is always responsible for promoting one’s own books, publishing with an established publisher accesses one to roads, connections, and certain avenues, such as book clubs and other literary societies and organizations which wish to only deal with authors who have been validated by the establishment. Self-published authors are often left outside or are locked from these organizations or societies. Again, the established publisher represents, ideally, immediate access to mass markets and elite persons and organizations. In reality, most writers, even after acquiring these mainstream deals, still find themselves having to pound the pavement to sell their books. So, validation is the major pro for publishing with an established publisher.

This validation is important if one plans to make a career as a college or university professor. If this is one’s pursuit, then the importance of accredited and validated research must be realized. One of my mentors, Dr. Reginald Martin, professor of English at the University of Memphis and editor of the best-selling anthology Dark Eros, puts it this way.

“If you’re in the scholarly writing game, it is not only validation that you receive by being published by a commercial publisher; it is also job perks and being allowed to keep the job. This is very important for younger black scholars to understand. Walt Whitman’s self-publishing of Leaves of Grass (1843) would still be the great book it is, but, if Whitman were a professor, he’d get kicked out of his job because only peer review and publishing by a large house matters to a university. This is wrong, and you can easily see how this will only re-create the same boring material and ideas, but that’s the way it is” (Martin 1999).

Most established publishers like Penguin Random House, St. Martin’s Press, etc., will not accept unsolicited manuscripts from writers who do not have agents. Often, one will find oneself submitting to agents in the very same manner that one will submit to a publisher. Finding the appropriate agent for one’ book is a hit and miss process. The Writer’s Guide as well as other publications has a list of agents as well as the types of books and writers they sign. You can also locate their websites for more information as to what types of writers they sign.

Before any writer submits to a publisher or an agent, it would be a good idea for a writer to subscribe to and submit to local, regional, national, and international journals. Journals are a way by which a writer is able to gain a feel for what is being published in the field or a particular genre, hone one’s skills, and submit, hoping that even in rejection one will gain some type of feedback. A writer should also submit one’s work to various emerging and established writers. They, of course, will have very demanding schedules, which will not allow them to respond to every inquiry, but I have found that most will take the time to send some comments about one’s work if one includes a SASE.

Also, attempt to identify persons working in the field like critics or scholars. One will usually find these individuals through journals and university presses. That is, identify certain colleges, universities, or writing programs and send work to them. The feedback one receives from journals and other writers will allow one to measure one’s talent and growth as a writer and will also act as marketing tools when one approaches an agent or a publisher. It is always an added plus to be able to say that “you should publish me because my work has been hailed by this renowned scholar, critic, or artist”. This makes journals and publishers “sit up” and “take notice”. In fact, I would suggest that a beginning writer work the journal circuit for about two years before submitting work to an agent or a publisher. Along with submitting to journals, join a writer’s group that is well connected to people who publish. Before joining a group, ask the members questions regarding their aesthetic, writing/publishing successes and failures, and their publishing desires. It is one thing to participate in a creative writing group where one is able to grow, but it is more effective to participate in a creative writing group that has the connections to get one’s work considered for publication in journals, anthologies, and by publishing houses. Ultimately, writers should join writing groups that have the same focus, drive, and direction as one has so that one can be nurtured and educated by similar and more mature writers. Cave’ Canem, for example, is an excellent example of this, and there are other writer’s groups whose goal is to develop writers and provide access to publishing. The goal is to connect to groups, conferences, and organizations, especially the ones that sponsor writing contests. These seminars, retreats, and contests often lead to publishing opportunities.

Another interesting trend is the manner in which established publishers are looking to independent or self-published writers. That is, once a writer has proven that one can sell a certain amount of books by pounding the pavement, often larger publishing houses “come-a-calling”. So, self-publishing is no longer just an avenue for writers who want to own and control their work and ideas. Self-publishing is now a very viable vehicle, which allows writers to gain the attention of larger publishers. Depending on one’s knowledge of contracts and the publishing business, one may need an agent. Agents often create query/proposal letters for their writer’s books. It is a good idea for the writer to know how the construct a query/proposal letter so that one can retain some amount of control as to how one or one’s work is marketed. One can obtain a copy of a query/proposal letter online or from any college textbook that is used for a professional or technical writing course. If all else fails, check to see if there is a grant/proposal writer in your area. They usually work for ten percent of the proposed amount. Some will only charge if the grant/proposal is accepted, and others want their fee upfront. Check the local small business or community business development centers/institutions to see if they can refer a grant/proposal writer. However, the core of the query/proposal letter should include an abstract/overview of the work, a table of contents, data showing how these types of books generally sell, and data of the target audience’s buying habits—especially as it relates to this type of book. The query letter must clearly present the theme/central issue/focus of the book and that there is an audience for the work. But, do not waste time “telling” them how great your work is; allow the work’s message, craftsmanship, and potential audience to “show” the work’s potential.

Self-Publishing:

The pros of self-publishing are:

- Not having to wait to be validated, which is important if one is a doing something that is not being regularly marketed,

- Controlling what one writes and publishes, when one writes and publishes, and how often one writes and publishes, and

- Being able to directly reap the artistic and economic benefits of one’s hard work of pounding the pavement.

The cons of self-publishing are:

- Publishing work when, as an artist, one may not be ready or well-crafted and

- The money that one must invest. People who decide to self-publish must understand that, often, one only gets one chance to make a good impression, and poorly-crafted work will follow a writer for one’s entire life. As poet Kysha Brown Robinson, co-founder of Runagate Press and a member of NOMMO Literary Society, stated: “I would rather take my time and publish one good poem than publish ten poorly-crafted poems.”

Self-publishing is a good idea if the writer has a balanced and level head, which is driven by a desire to produce well-crated work and not driven by the desire just to publish or to gain stardom. A person who self-publishes must create a system of checks and balances so that one’s work is not guided by a self-absorbed ego. This, I submit, is the most difficult task of self-publishing, being objective, if such a thing is possible, about one’s own work. Thus, the self-published writer must continuously identify and engage writers and critics whom one respects. So, every writer is always submitting work to someone other than oneself. Even when self-publishing,

every writer needs an editor. An effective editor is not just correcting grammar and spelling; the editor is also helping to make the work more powerful by honing the writer’s technique and delivery because sometimes writers are at a loss as when to add or subtract. For instance, I can add imagery, dialogue, action, setting,

etc. to enhance or improve a work, but I am too emotionally tied to my work to delete any of it. This does not mean that I think that everything that I write is well-crafted, but my writing comes from such an emotional place that to delete something is akin to removing a part of me: my body or my emotions. An editor is not as connected to my work and can read it objectively and, dare I say it, rationally, and can make objective decisions about what parts and techniques are being effective and which are not. Of course, professional editors are expensive, often being paid by the word or the page. But, if one can identify an English teacher with whom one has a good relationship or any English teacher who may be interested in the experience of editing or just willing to provide a favor or act of kindness, one can save some money. It also helps if one has friends who read a great deal. They may also be able to help. But, one needs someone to put a second, third, or even fourth pair of eyes on one’s work to ensure that it is readable and well-crafted.

Self-publishing is a good idea if the writer has a balanced and level head, which is driven by a desire to produce well-crated work and not driven by the desire just to publish or to gain stardom. A person who self-publishes must create a system of checks and balances so that one’s work is not guided by a self-absorbed ego. This, I submit, is the most difficult task of self-publishing, being objective, if such a thing is possible, about one’s own work. Thus, the self-published writer must continuously identify and engage writers and critics whom one respects. So, every writer is always submitting work to someone other than oneself. Even when self-publishing,

every writer needs an editor. An effective editor is not just correcting grammar and spelling; the editor is also helping to make the work more powerful by honing the writer’s technique and delivery because sometimes writers are at a loss as when to add or subtract. For instance, I can add imagery, dialogue, action, setting,

etc. to enhance or improve a work, but I am too emotionally tied to my work to delete any of it. This does not mean that I think that everything that I write is well-crafted, but my writing comes from such an emotional place that to delete something is akin to removing a part of me: my body or my emotions. An editor is not as connected to my work and can read it objectively and, dare I say it, rationally, and can make objective decisions about what parts and techniques are being effective and which are not. Of course, professional editors are expensive, often being paid by the word or the page. But, if one can identify an English teacher with whom one has a good relationship or any English teacher who may be interested in the experience of editing or just willing to provide a favor or act of kindness, one can save some money. It also helps if one has friends who read a great deal. They may also be able to help. But, one needs someone to put a second, third, or even fourth pair of eyes on one’s work to ensure that it is readable and well-crafted.

Again, self publishing is expensive. It is expensive to publish one’s books, and it is expensive to continue to re-print older books while simultaneously publishing new work. And the expenses do not stop there. Once a book is published, one has the responsibility for delivering complimentary copies all across the planet, which can be anywhere from thirty to one hundred and fifty complimentary copies, and this must be included in one’s budget, not to mention postage for all of this. To distribute thirty complimentary copies at three dollars a pop is ninety dollars. Bulk mail helps, but it is not as helpful as one may assume. Yet, the complimentary copies list is a must for the self-published writer. While one’s book is in the editing process, start compiling a list of writers, magazines, newspapers, book clubs, and organizations. Once one has a thorough list, send a complimentary copy of the manuscript to the people on the list for reviews. Some of the reviews (the most enthusiastic) can be used for the back of the book. The goal is to inform as many people as possible that one has a book that will be released soon. Then, once the manuscript is in final book form, send the finished version of the book to the people on the list. Every writer’s list will have some of the same names and some different names. It depends on one’s style and subject matter. When I was first started, I simply created a wish list of folk I wanted to know about my work and sent them a copy. Some people did not reply, some people replied favorably, and some replied not so favorably. No matter the response or reply, it is all part of the process of informing the public that one has a book for sale. Additionally, one still must be willing to submit work (poems, short stories, and chapters from books) to various magazines and newspapers to be published. Again, it does not make sense to have a book for sale when nobody knows that it is available. By publishing work in various newspapers and magazines, people can read excerpts of one’s work and then decide to purchase a copy of one’s book.

An added issue is when authors wish to have illustrations within the text of the book. Photos, of course, do increase the cost of printing. Ordinarily, printers charge somewhere in the area of seven and thirty-five cents per page, depending on the quality of the paper and the quantity of the copies. (A high volume order of books decreases the price.) Color copies can increase the cost of copying a page to the range of one dollar to one dollar and fifty cents per page, again depending upon the quality of the paper and the quantity of the copies. Black and white copies are a bit different. If one is attempting to get a high quality gloss looking black and white, then the printer will shoot it with a laser printer or copier (the same method as color) and will charge the same amount as a color. If one is able to reproduce those black and white illustrations by way of a standard copier, then it should not increase the cost at all, since the printer is not required to do any additional work. Of course, always ask. Here is the general rule of thumb. No matter what one needs done to one’s books, always try to pay no more than three to four dollars per book. This, of course, keeps your price for the book low. Three dollars should really be the limit, and one will probably purchase about 500 copies minimum to get a cost of three dollars or lower. Of course, on-demand printers and publishers are now more feasible than traditional printers, and I would recommend going online to review what they offer. Some writers prefer on-demand publishers while others prefer on-demand printers. As always, I suggest that one researches to secure what works best for each writer. I personally prefer on-demand printers, such as Lulu.com or CreateSpace.com because of the quality of their work, I can control as much of the book-crafting/layout process as I desire or allow them to do it, and they allow me to keep my books digitally archived at no costs until someone desires to purchase copies of my books. Others prefer on-demand publishers, such as Xlibris, because along with the other services they also offer marketing services for an additional fee.Even though I was not ready, not as well-crafted as I needed to be, self-publishing allowed me to gain the attention of some folk who would say, “Most of this stinks, but there are some moments here that let me know that you seem to have talent.” With hindsight being twenty-twenty, I should have worked the journal circuit more, even if I was going to self-publish. Even if one plans or desires to self-publish, one must gain feedback from journals, university scholars, and critics as well as established creative writers. Feedback can come in the form of writers’ groups, such as Cave’ Canem listed above. Even if one does not desire to be published by a major company, a writers group can connect one to schools sponsoring conferences, book clubs, editors of anthologies, and magazines, which can all help promote one’s self-published work. This is important because a self-published writer will need some validation from somewhere else since one will not be validated by the larger publishers.

What is this validation of which I keep speaking, those little comments on the back of books that tell a potential reader, “Hey, buy this book; it’s good.” The real fact of the matter is that most readers must have new writers validated by someone else before they will “pick up” or read the work. As such, word of mouth is always the best advertisement. It can make or break a writer. These comments that one will be receiving from various members of the writing community will help to propel one’s work to a larger reading audience.

Yet, it must be realized early in one’s endeavors that this validation sought by a self-published author will be difficult to find. Further, Martin confirms that “even if you self publish, the general rule for reviews is that no organization will review the book unless it also came out in hard cover. Again, this is silly, but this is the current state of trying to get a book reviewed by most southern journals and any large media outlet” (Martin 1999). Also, most large or more notable journals and periodicals tend not to review unsolicited work. Most self-published authors must hope that their work makes enough noise in the smaller periodicals that larger, more noted journals will be called to the work’s attention.

Again, when one is self-publishing, everything is one’s responsibility. But no matter which road one chooses, always copyright one’s work. If someone publishes one’s work, one can give them permission to use one’s work, but the copyright allows one to retain all the rights. I tend to copyright all my work about every six months. Others wait and copyright only their complete manuscripts. As a rule of thumb, I never submit work to anyone that is not copyrighted. One obtains a copyright from the Library of Congress, Copyright Office, 101 Independence Avenue, S.E., Washington, D.C. 20559-6000. Or, one can go online and print a form at http://www.copyright.gov/forms. It costs eighty-five dollars per copyright. That is eighty-five dollars to copyright one poem or eighty-five dollars to copyright a collection of poems. That is why every six months I copyright a collection of work. However, one can also complete an online registration to copyright one poem, or one short story, or one novel for thirty-five dollars. For more information about online download the single application.

One issue that always arises is when self-published authors submit or allow their work to be included in anthologies. Generally, when a publisher applies for a copyright of an anthology, one is applying for a copyright for the entire work in the name of the publisher. That copyright covers the work as a whole. That is, the publisher’s copyright only covers the works inasmuch as they are collected and complied to create one cohesive work, allowing the author to retain all rights to present, submit, or sell that particular anthology or collection of works. The rule is: if one owns a copyright of a work and does not surrender or sign it away, then the work remains the writer’s until the writer signs something giving that right to someone else. The only problem that can arise is if one does not already have the work copyrighted before the publisher applies for a copyright for the anthology. Yet, unless one signs something specifically surrendering, relinquishing, or giving the rights of one’s work to someone, then one’s rights are covered or protected. There can only be a problem if a publisher wishes to claim that one’s work was done as work for hire. That is, the writer specifically produced a certain work to be used by the publisher for a particular publication. In this case, it will be best that one has one’s work copyrighted. Here, again, as long as one does not surrender, relinquish, or sign away one’s rights, then one is protected. The publisher’s copyright covers the anthology as a whole, but the writer still retains the rights of one’s work. Yet, publishing work in an anthology is a great way to earn or gain promotion for one’s lager work. For instance, if one’s poem, short story, or an excerpt from one’s novel is published in an anthology, then a larger reading base will have access to one’s work and may want to purchase the entire work.

One issue that always arises is when self-published authors submit or allow their work to be included in anthologies. Generally, when a publisher applies for a copyright of an anthology, one is applying for a copyright for the entire work in the name of the publisher. That copyright covers the work as a whole. That is, the publisher’s copyright only covers the works inasmuch as they are collected and complied to create one cohesive work, allowing the author to retain all rights to present, submit, or sell that particular anthology or collection of works. The rule is: if one owns a copyright of a work and does not surrender or sign it away, then the work remains the writer’s until the writer signs something giving that right to someone else. The only problem that can arise is if one does not already have the work copyrighted before the publisher applies for a copyright for the anthology. Yet, unless one signs something specifically surrendering, relinquishing, or giving the rights of one’s work to someone, then one’s rights are covered or protected. There can only be a problem if a publisher wishes to claim that one’s work was done as work for hire. That is, the writer specifically produced a certain work to be used by the publisher for a particular publication. In this case, it will be best that one has one’s work copyrighted. Here, again, as long as one does not surrender, relinquish, or sign away one’s rights, then one is protected. The publisher’s copyright covers the anthology as a whole, but the writer still retains the rights of one’s work. Yet, publishing work in an anthology is a great way to earn or gain promotion for one’s lager work. For instance, if one’s poem, short story, or an excerpt from one’s novel is published in an anthology, then a larger reading base will have access to one’s work and may want to purchase the entire work.

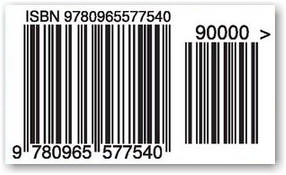

Once one has secured a copyright and reviews or comments, it is time to put the work into book form. This means finding a printer and acquiring ISBN (International Series Book Number) and LCCN (Library of Congress Catalogue Number) numbers. An ISBN is the social security number of a book. It allows the book to be tracked and sold anywhere on the planet. The LCCN is the social security number of your book for the world library systems. It allows the book to be tracked and loaned through any library system on the planet. To receive an ISBN write to R. R. Bowker (U.S. ISBN Agency), 630 Central Ave., New Providence, NJ 07974-1154, Phone: 877-310-7333, info@bowker.com, or go to https://www.myidentifiers.com/. Once can complete the form online or print the application and mail it. Ten ISBNs cost $275.00, and 100 ISBNs cost $575.00. For more ISBNs contact the website for pricing. R. R. Bowker will assign the numbers to the entity one lists under company name.

One cannot transfer or sell the numbers to anyone else. If one engages a joint project with someone, one’s ISBNs must still be listed to one’s named entity, or the two partners must apply for an ISBN jointly. Because most if not all retailers require that books have a bar code, there is a place to order a specific bar code for a specific ISBN on the ISBN application. 1 – 5 bar codes cost $25.00, 6 – 10 bar codes cost $23.00, and 11-100 bar codes cost $21.00. Also, as of January 1, 2005, the book industry began adopting the use of a 13-digit ISBN. This change aligns the ISBN identifier with other worldwide product numbering systems, helping promote an efficient global supply chain structure.

As of 2007 all books must be compliant with the 13-digit ISBN. If one already has an ISBN, one can get it converted for free at

http://www.isbn.org/ISBN_converter. If one is applying for one’s first ISBN, one will be automatically given a 13-digit ISBN.

One cannot transfer or sell the numbers to anyone else. If one engages a joint project with someone, one’s ISBNs must still be listed to one’s named entity, or the two partners must apply for an ISBN jointly. Because most if not all retailers require that books have a bar code, there is a place to order a specific bar code for a specific ISBN on the ISBN application. 1 – 5 bar codes cost $25.00, 6 – 10 bar codes cost $23.00, and 11-100 bar codes cost $21.00. Also, as of January 1, 2005, the book industry began adopting the use of a 13-digit ISBN. This change aligns the ISBN identifier with other worldwide product numbering systems, helping promote an efficient global supply chain structure.

As of 2007 all books must be compliant with the 13-digit ISBN. If one already has an ISBN, one can get it converted for free at

http://www.isbn.org/ISBN_converter. If one is applying for one’s first ISBN, one will be automatically given a 13-digit ISBN.

After receiving an ISBN, one will need a library catalogue card number (LCCN), which is also referred to as the PCN. This number is free, but cannot be obtained without an ISBN and a title page of the proposed work. The form is very self explanatory. Write to Library of Congress, Cataloging in Publication Division, 101 Independence Ave., S.E., Washington, DC 20540-4320 or go online to http://pcn.loc.gov/pcn007.html. They also request that after one receives the LCCN and one’s book is published, that two copies of the book to be filed there. Submit those mandatory deposits to Attn: 407/Mandatory Deposits, Compliance Records Unit, Library of Congress, Cataloging in Publication Division, 101 Independence Ave., S.E., Washington, DC 20540-4320. When one receives one’s ISBNs, one will also receive a Pre-Publication form from R. R. Bowker. Six months before the publication of one’s book, complete and return this form to R. R. Bowker. This allows R. R. Bowker to list one’s book with all booksellers. So if I know a writer’s name, or the book title, or the ISBN, I can walk into any bookstore and ask for your book. Even if they do not have the book in stock, they will have the ability to order the book directly from you. This is how I sell all of my books. It is pre-pay only. They send me a check, and I send a book. I still get at least one order a week for from Europe for The Lyrics of Prince. I have never been to Europe, and I am not planning to go. But as long as I remain updated with R. R. Bowker, people can order my books from anywhere in the world.

One must also be persistent with Amazon.com,

Barnes and Noble, and the other large dealers about keeping one’s books listed. Periodically, I go online and check to see if I can find my books. At the moment, all of my books are listed at Amazon.com

,

Barnes and Noble, and

my website. Finally, when publishing a book, it generally cost about $1,800 for a quality printer to print 500 books. This is about $3.60 per book. For years I used a local printer, but it just became more feasible to use a national printer, such as Lulu.com or

CreateSpace.com. I liked being in close contact with the local printer, but once on-demand printers began offering easy access through uploading and web chats it just made more financial sense to use them. Always check with several printers in one’s area as well as with national printers. It will then cost about $150.00 to $300 in postage to send complimentary copies to journals, writers, and friends. Identify about 100 copies for promo. Book clubs are fine, but they generally only read and review fiction and essay. They tend not to read much poetry.

Writing is like all other professions. One must be a student of the trade. This means that one must obtain a subscription or two in order to know what is being published and what the current conversations/issues of the field are, allowing one to grow as a writer. One should also join some regularly meeting workshop. A good writing workshop stresses reading and writing activities and exercises that challenge one to work beyond one’s comfort zone, which forces one constantly to evaluate one’s skills and grow. There are several online workshops that can also be used to supplement one’s local workshop. An excellent online workshop is deGriot Space, which is facilitated by Askhari. For information to join, contact her at deGriotSpace-owner@yahoogroups.com or

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/deGriotSpace.

Writing is like all other professions. One must be a student of the trade. This means that one must obtain a subscription or two in order to know what is being published and what the current conversations/issues of the field are, allowing one to grow as a writer. One should also join some regularly meeting workshop. A good writing workshop stresses reading and writing activities and exercises that challenge one to work beyond one’s comfort zone, which forces one constantly to evaluate one’s skills and grow. There are several online workshops that can also be used to supplement one’s local workshop. An excellent online workshop is deGriot Space, which is facilitated by Askhari. For information to join, contact her at deGriotSpace-owner@yahoogroups.com or

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/deGriotSpace.

A good reference point for workshops, conferences, publications, and journals is a free listserve operated by Kalamu ya Salaam. He is an institution within the institution of writing. Kalamu ya Salaam is one of the driving voices behind the African American Southern Literary scene. Salaam’s work includes his latest book What Is Life? (Third World Press) and his poetry CD My Story, My Song (AFO Records). To join, simply e-mail him at kalamu@mac.com. He has a cyberdrum network by which he sends e-mails to anyone on the list about magazines, book companies, journals, conferences, and other publishers who are looking for writers to submit their work. One will receive about ten daily e-mails on submissions and discussions around the country.

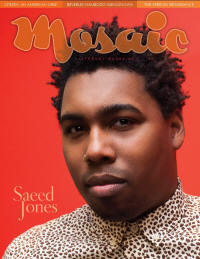

Next, subscribe to at least two literary journals. One should be very academic, and the other should be very culturally astute and wise so that one is exposed to the best of both worlds. Academic journals focus on the form, genre, and structure of writing. Culturally artistic journals focus on the amalgamation of form and culture. Subscribing to both types of journals allows one to grow in various areas. Do not worry if many of the articles look intimidating. One must know theory (elements of literature) to write well or effectively. I use

Callaloo ($40 yearly, Johns Hopkins University Press, Journals Publishing Division, 2715 North Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363, 410-516-6987) as my academic journal and

Mosaic Magazine ($15.00 yearly, 314 W 231 St #470, Bronx, NY 10463, as my cultural journal.

African American Review (Department of English, Saint Louis University, Humanities 317, 3800 Lindell Blvd., St. Louis, MO 63108) is also a very well established scholarly journal.

Next, subscribe to at least two literary journals. One should be very academic, and the other should be very culturally astute and wise so that one is exposed to the best of both worlds. Academic journals focus on the form, genre, and structure of writing. Culturally artistic journals focus on the amalgamation of form and culture. Subscribing to both types of journals allows one to grow in various areas. Do not worry if many of the articles look intimidating. One must know theory (elements of literature) to write well or effectively. I use

Callaloo ($40 yearly, Johns Hopkins University Press, Journals Publishing Division, 2715 North Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363, 410-516-6987) as my academic journal and

Mosaic Magazine ($15.00 yearly, 314 W 231 St #470, Bronx, NY 10463, as my cultural journal.

African American Review (Department of English, Saint Louis University, Humanities 317, 3800 Lindell Blvd., St. Louis, MO 63108) is also a very well established scholarly journal.

I am not suggesting that one “rush out” a get all these journals. But, I want young writers to understand that writing is more than what we feel. One may feel or think something, but one must develop the tools to articulate specifically and effectively what it is that one is thinking and/or feeling. Even if one may have good ideas and tools, one must get to work developing them. No matter what road a writer chooses to follow, only well-crafted writing will get a writer where one wants to go.

There are four additional books that all beginning African American writers should have in their possession: The Norton Anthology of African American Literature edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Trouble the Water: 250 Years of African American Poetry and Black Southern Writers both edited by Dr. Jerry W. Ward, and Call and Response edited by Dr. Trudier Harris. These four anthologies provide a cohesive understanding of the African American literary cannon. They also provide an idea of how the publishing of African American literature has changed and evolved. Specifically, these anthologies show how self-publishing and small/independent publishing have always been a part of the African American publishing tradition and how it remains a necessary mainstay.

As for self-publishing, I am broke but happy. I own my work. I control my work. I work at my own pace, which is cool since I know that I will work harder at selling my books than anyone else. Nikki Giovanni began as a self-published author, riding around with books in her trunk. Third World Press, which is now an international publishing force, began with Haki Madhubuti selling single poems at a barber shop. Gwendolyn Brooks and Amiri Baraka were visible and consistent supporters of independent and self-publishing. Self-publishing has been a major vehicle for African American writers who have been and are still very much locked or excluded from the mainstream process. Self-publishing and independent publishing appeals to many African Americans whose voices and subject matters have been and remain contradicting to mainstream publishing. When African American writers have needed a tool to raise their voices about their situation in American and that voice was no longer en vogue, self-publishing and independent publishing remained as excellent vehicles, ensuring that all voices will be given the opportunity to be heard. Yet, self-published writers must always realize that “how” one says something is as important as “what” one says. Thus, all the people I have mentioned are not memorable because they self-published but because they self-published quality work.

Original

Version

from

Prose: Essays and Letters

Original

Version

from

Prose: Essays and Letters

Works Cited

Martin, Reginald. “Personal Interview.” Spring, 1999.

Related Links

AALBC Prints Books

AALBC Prints Books