What I’d Say: On Writing “Frankie Five Hundred”

by Michael A. Gonzales

Published: Wednesday, March 12, 2025

Recently my short story “Frankie Five Hundred” was published on the literary website Evergreen Review. Founded in 1957 when it was launched by Grove Press publisher Barney Rosset, the magazine was my introduction to the writings of Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), Eldridge Cleaver, Susan Sontag, Norman Mailer, Malcolm X, John Rechy, and other scribes who were considered radicals. I discovered Evergreen in 1985 when I was a messenger in New York City and visiting bookstores daily.

Frances “Frankie” Gonzales in 1959

Frances “Frankie” Gonzales in 1959I bought the telephone book-thick Evergreen Review Reader, and it changed my literary life. Since then, Evergreen Review has had a few deaths and rebirths in its long history, but it was most recently brought back to life in 2017 by publisher John Oakes, editor-in-chief Dale Peck, and fiction editor Jeffery Renard Allen. Hailing from Chicago, Allen is an acclaimed novelist (Rails Under My Back) and short fiction writer (Fat Time and Other Stories), and he was the person who decided to take a chance on my long tale of a young woman coming of age in 1959 Harlem.

I finished the first draft of “Frankie Five Hundred” in 2017 when it was initially composed for an anthology. I wound up withdrawing it when the editor and I clashed over the story’s direction. Over the years, I’ve worked on the narrative, added scenes, deleted characters, and changed the point of view to get it right. I submitted various versions of “Frankie Five Hundred” to a couple of journals, but they either thought it was too long or they just didn’t get it. Not everyone can relate to a free-spirited Black woman from any era, but I never would’ve imagined that it would eventually be published in the same radical magazine that inspired and influenced me 40 years ago.

As a native son of Harlem born in 1963, the origin of “Frankie Five Hundred” began in childhood when my mother, Frances (Frankie, as my godfather Hans called her), recounted her years as a young woman relocating from Pittsburgh to New York City in the 1950s. She attended George Washington High School, took modeling classes at Ophelia DeVore School of Self-Development and Modeling (where Diahann Carroll and Cicely Tyson also studied), worked at Doubleday Books on 5th Avenue, socialized with friends, went to jazz clubs with Uncle Carl, and moved out of her mother’s apartment.

Having heard these stories for decades, I vowed to one day use them as the seeds to grow a different kind of Harlem tale. While there were various inspirations behind “Frankie Five Hundred,” the most prominent include Truman Capote’s classic story “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” Miles Davis’ brilliant Kind of Blue, the photographs of Gordon Parks, Roy DeCarava, and Bert Andrews, and John Cassavetes’ directorial debut Shadows, all of which conjured images of late-1950s New York City. There was also the website The 1959 Project, which featured wonderful photos, album covers, and articles on jazz, and my constant jammin’ of the Ray Charles house party gem “What I’d Say.”

Other texts that were helpful in my research were Our Kind of People: Inside America’s Black Upper Class by Lawrence Otis Graham and The Cotillion by John Oliver Killens. Both books gave me insight into the world of Jack and Jill of America, which in 1959 was still known as a Black society organization for bougie Black kids and teens with “good hair” and light skin. These books also took me into the world of Debutante Balls, which Frankie was obsessed with from afar, reading about them in the Pittsburgh Courier, Jet, and later, the Amsterdam News.

While many movies and books depict young Black folks in 1959 as politically minded and guided by civil rights, the truth is, not everyone in Harlem was attending Malcolm X’s speeches (though Frankie does listen to him for a few minutes before her modeling class) or had radical thoughts about race. Though they were proud of being Black, or “Negro,” which was still the in-vogue term, everyone wasn’t fighting the power. Many strived to uplift the race through their accomplishments—going to college, being the first Black in various professions, operating businesses, and setting an example for the community’s children.

“Frankie Five Hundred” was based on my mother’s memories, but I didn’t set out to write a biography. Like a giant jigsaw puzzle, I scattered the pieces (and threw a few away) to create the kind of story I’ve always wanted to write. Besides Frankie, my favorite character is Helen Jordan, who was based on real-life Harlem socialite Hazel Sharper. Her son Ralph was my mom’s best friend, and they lived in the beautiful Deerfield apartment house on 145th Street and Riverside Drive. In the story, Frankie subleases the grand apartment from Helen, who has been her mentor since high school.

Harlem itself is another character in the narrative, set in the community’s various bars (Carl’s Corner, Jocks), the Theresa Hotel, Club Savoy, the Bowery Bank Building, and the Palm Cafe, a long-closed restaurant that hosted fashion shows in the ’50s. Being a model in those days involved walking in local shows for $25 or less, posing in department store windows (as fellow Ophelia DeVore grad Bani Yelverton did), and hoping that the handful of Black magazines (Ebony, Sepia, Hue) might use you to illustrate an article or advertisement.

Harlem itself is another character in the narrative, set in the community’s various bars (Carl’s Corner, Jocks), the Theresa Hotel, Club Savoy, the Bowery Bank Building, and the Palm Cafe, a long-closed restaurant that hosted fashion shows in the ’50s. Being a model in those days involved walking in local shows for $25 or less, posing in department store windows (as fellow Ophelia DeVore grad Bani Yelverton did), and hoping that the handful of Black magazines (Ebony, Sepia, Hue) might use you to illustrate an article or advertisement.

After thinking about writing “Frankie Five Hundred” for years, sitting down to put it together was an interesting process. In my head, the stories became a Technicolor movie, and I could damn near see each frame as the words revealed themselves on the computer screen. Though I didn’t write an outline, I took extensive notes on the characters and their environments. Alongside my friend Sandra Jamison, a former Harlem resident who helped me with research, I took pictures of the Deerfield, Riverside Drive, and various landmarks in the community.

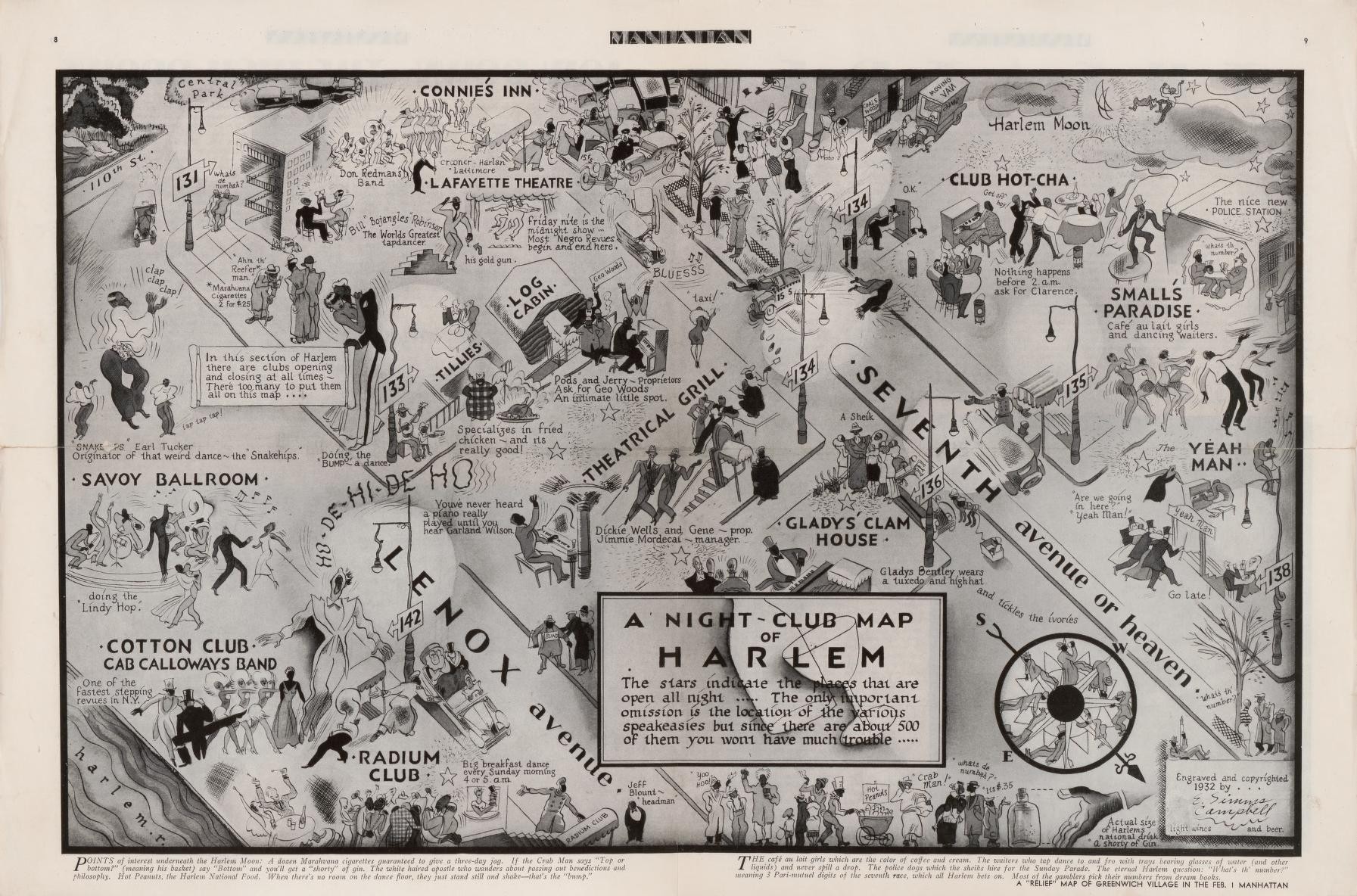

When “Frankie Five Hundred” was published on March 8, 2025, I was thrilled to finally see it in print. Evergreen Review did a stunning job, illustrating the story with an E. Simms Campbell nightclub map of Harlem (see below) as well as photos by Gordon Parks and Walker Evans. However, the real test came when I sent it to my 87-year-old mom, who still reads more books a week than me. Waiting for her judgment, I was nervous she might hate it and feel as though I had exploited her life. But when we finally spoke that day, her words to me were, “You nailed it.” With the exception of “I love you,” I can’t think of three words that have brought me more joy.

Michael A. Gonzales writes regularly for various publications, including CrimeReads, Oldster, Memoir Land, and Open Secrets. His fiction has appeared in Killens Review, Brown Sugar 3 (edited by Carol Taylor), and Oxford American.