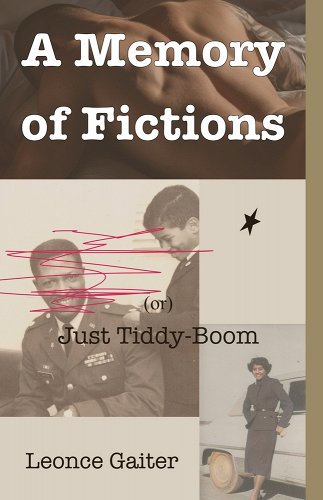

Book Review: A Memory of Fictions (or) Just Tiddy-Boom

Reviewed by:

Robert FlemingSo many books written by gay, Black men do not explore the inner emotional terrain of their character. That is why this vast, drama-packed novel, A Memory of Fictions (or) Just Tiddy-Boom, by Leonce Gaiter, a wandering wordsmith from New Orleans and all points North, puts its best foot forward. The narrative ride is a wild one.

The main character, Jessie Vincent Grandier, wanted to break free of the rigid, suffocating social and cultural morality that defined his life. Raised by a bright-skinned, bourgeois New Orleans Creole mother and a simplistic, bayou-poor military father, Jessie tried to stretch his wings and soar into the world. His father’s immediate family consisted of thirteen children and Grandier Sr. wanted to have a son to carry on the family name. Doctors had advised Jessie’s mother, Lulene, not to have more children after his two older sisters were born.

Before the reader takes on a final analysis of the book, the publisher describes its contents “as a modern, jazzy take on the bildungsroman,” with plenty of the literary and visual images tossed into the pot. Glimpses of personal memoir, references to music and bits of song lyrics, diary entries, official documents, poetic verses, doses of humor, even a death certificate all appear here. Gaiter, the author of the novels I Dreamt I Was in Heaven (2011) and Bourbon Street (2020), casted a wide net to depict the stunningly original portrait of a Black man, who invites adventure, mayhem, quick decisions without acknowledging the consequences.

Jessie bucked the religious tradition by choosing the male form over his mother’s wishes. As a good Catholic, Lulene expressed, “Regarding ‘fairies’ or ‘queers’, she promised to kill any son of hers should he turn thus. Jessie took her words to heart and from an early age, squelched any and all sexual stirrings.” As a young boy, Jessie lived in fear of his parents. He was the object of his father’s wrath and his mother’s disapproval. However, once, when he was eleven years old, his mother placed him on her lap and said, “You know I love you.” Jessie replied, “I love you too.”

Still, he became attracted to men’s undergarments, bulges, and jockstraps. A master of denial, although he masturbated to these images, he refused to recognize the sexuality of his identity. Jessie’s obsession of male sexuality and sheer boredom undercut his English department class at Harvard and the summer of his sophomore year at NYU in a film writing course. Meanwhile, Lulene acquired an unbearable headache that would not go away and a young doctor at Walter Reed Army Medical Hospital suggested she take an aspirin and rest. Later, she went into a coma with minimal brain activity, being declared clinically dead.

Often, Gaiter’s words and images dig deep as he assumes the cosmic keys to his consciousness. “You will not know what it’s like to carry Gods inside you and to heed those outside yourselves. You will never see the ghosts and feel the fates’ weight on you, you trying to outrun the past while it effortlessly passes you by, laughing.”

The conflict between father and son is highlighted by the negative feelings between Grandier and Jessie. For the man, he always called him crazy, a mystery and an aberration since his birth. They hated each other, so much that Grandier wished the boy would burst into flames.

Jessie felt a part of the “square” world, a society that valued conformity and uniformity. “But his parents and his church and those all around him had hopes and dreams to which they clung tenaciously and a faith they followed with the fervor of madmen. They took jobs and had children and acted as if their tiny little spots in this big world meant something profound. He didn’t know how they did it. He couldn’t find their zeal within himself.”

For Jessie, regarding all the people in his life who had passed, death meant closure, and he had other ideas: “Death wasn’t some grim-faced specter in hooded blacks with a scythe. Death was a Warner cartoon. It gooses you and gives you wedgies, probably plants fake dog shit and speaks with a lisp. The secret, he supposed, was to make one’s life as ridiculous as one’s end was bound to be.”

Like other books of this ilk, this novel concerns the sober topics of identity, individuality, responsibility, race, and family loyalty. This is not the first time these topics have been explored and used creatively. Witness the works of Paul Beatty, Leon Forrest, Max Frisch, Marlon James, Ben Okri, and Ishmael Reed. This book gives them a run for the money with its candor and raunch intact.

Leonce Gaiter’s A Memory of Fictions contains many universal truths, several cultural cliches and myths, and spot-on observations on morality, identity, racial conflicts. Gaiter’s storytelling is descriptive, and the narrative often has a conversational tone. The transitions in which scenes jump from one point in time in the characters’ lives to another could have been smoother.

One major drawback is the book’s overreliance on literary inserts, making it too packed with distractions. Still, this novel is worthy of a read, especially if you cherry-pick the more significant segments.