Book Review: Dark Matter: Reading the Bones

Reviewed by:

Chris HaydenIf It Ain’t Speculative and It Ain’t Fiction Need Black Folks Read Speculative Fiction?

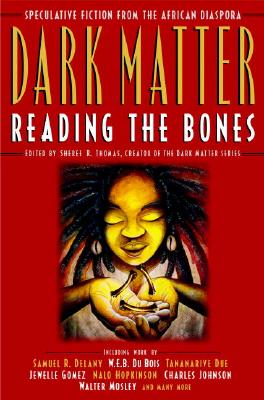

It distresses me when I can grant only qualified approval such an ostensibly worthy effort as Dark Matter: Reading the Bones, the second anthology from Editor Sheree R. Thomas that is intended to introduce the reading public to the works of speculative fiction by African American Writers.

Speculative fiction is the term coined in the ’60s by New Wave Science Fiction Writers led by Harlan Ellison to differentiate their writings, which combined the conventions of science fiction with up to date literary techniques and a counter cultural political and social consciousness, from the garden variety Gosh Wow gadget and techno fetishistic (and often politically and socially conservative) science fiction published by Hugo Gernsback in the 20’s (in his Amazing Stories, the first publication devoted only to what he called “scientifiction” ) and nurtured by John W. Campbell, author and editor for years of the most influential magazine in the field Astounding (which became Analog), in the 40’s and 50’s.

Today in some circles speculative fiction means horror, supernatural and fantasy fiction as well: it might simply be any story or book whose premise proceeds from a question which begins, "What if—?"

- "What if people could come back from the dead?" (Premise of a horror or supernatural story).

- "What if magic worked?" (Premise of a fantasy tale).

- "What if people could travel to distant stars?" (Premise for the interstellar space travel/sci fi story).

Horror, supernatural and fantasy are as old as humanity, old as myth. Science fiction is of newer vintage; some trace it to the account of Ezekiel and the Wheel in the Hebrew Bible, others to the tales of the Greek Lucian of Samosata (125 AD), but most historians of science fiction will mark 1818, the date of the first publication of the novel Frankenstein by Mary Shelly as the birth date of science fiction.

Until recently writers, editors, fans and publishers believed that African Americans did not read speculative fiction. In large part this is probably because, as John Clute wrote in Science Fiction: The Illustrated Encyclopedia (1995) with regard to sci fi, "the genre was not designed to be written or read by the Dispossessed." They may also have believed that because, though Africans told myths and tales of Gods and heroes, and African Americans have had a lively folk tradition, until recently few African Americans authors have specialized in writing it.

The publishing industry was stuck in its own dead zone with regard to black readers until the publication of Alice Walker’s The Color Purple (1983) and Terry McMillan’s Waiting to Exhale (1990) awakened them to the existence of a large and robust black reading public.

The only black speculative fiction author of note until then was Samuel R. Delaney; his work was so race neutral and he was so faceless to the public at large few even knew he was black. Following the above developments Stephen Barnes and Olivia Butler broke out in the 80’s, followed by Tananarive Due and Nalo Hopkinson in the 90’s.

The works of these five authors, who are still the major African American speculative fiction writers, won awards and made bestseller lists, they gave interviews and appeared at Sci Fi and Fantasy conventions. At the same time black readers and fans started attending fan meetings organized by whites and held their own (such as the Black to the Future Convention held June 11-13, 2004 in Seattle). African American Spec Fiction web discussion groups such as Sci Fi Noir, Sci Fi Noir Lit and Afro futurism came online, where Blacks revealed that they liked Spider-man, Star Wars, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Stargate, The X Files, Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings but that they want to see and read more stuff like Spawn, Blade, Static and A Vampire in Brooklyn. Yet still the field continued to present, for the most part, in the words of John Clute " a vision that was not aimed at black readers" that was "propagandizing for one small interest group, the affluent whites."

Then came Dark Matter: The Anthology of Science Fiction, Fantasy and Speculative Fiction by Black Writers (2000) edited by Sheree R. Thomas.

That volume was ground breaking and eye opening, it included work by those specializing in the genre, plus stories and essays by established writers not really known for working in the field such as W.E.B. Du Bois, George R. Schuyler, Walter Mosley, Amiri Baraka, and Kalamu Ya Salaam; work by writers who should have long been included in the canon, such as Henry Dumas and Ishmael Reed; and it introduced us to new talents like Jewell Gomez, and forgotten authors like Charles R. Saunders, who had published Black sword and sorcery during the 1970’s. I can give Dark Matter: the Reading of the Bones: (hereinafter referred to as Dark Matter 2) an “A” for effort. But the stories here range, according to Lenora Rose in the online Green Man Review "from breathtakingly good to shockingly mediocre."

Why? I submit that the flaw is inherent in the substance of speculative fiction itself.

Let me admit here that my hands are not clean; I have written speculative fiction: comic books, several such stories in Cecil Washington’s Creative Brother’s Sci Fi Magazine— to my knowledge the only magazine solely devoted to Black Speculative Fiction—and a novel Vampyre Blues: The Passion of Varnado, an African American Vampyre Romance, which is due out in October. I will further admit that, for a number of reasons, the only form that I have found as hard to write is poetry.

Still, as the young folks say, I " got beef" with speculative fiction.

For one it ain’t Speculative It is a category of genre fiction and as an editor in the field is alleged to have told a wannabe writer, the fans "say that want new material, but what they really want is more of the same ol’ thing." The beasties and things that go bump in the night that we have learned to laugh at in movie and TV parodies populate horror fiction. Supernatural fiction is scary but not too scary, more Stephen King style American Horror-Lite than real, mind rotting nightmare spawning horror (then again, what could be more awful than The Middle Passage, Slavery, Segregation, the A-Bomb, genocide, AIDS, etc) For all the prognosticate boasting of science fiction it has not predicted much that real scientists had not already discovered when the stories were written. Either it was wrong (use of copper to produce nuclear energy) or it contained, even in your typical so called “hard “science fiction story, less information than that contained in any paragraph on a scientific subject in the World Book Encyclopedia.

Science Fiction writers editors and fans, who have an emotional and financial stake in the matter, often promote sci fi as a miracle stimulant that will induce and empower readers to embark on careers in science.

Alas, anyone who wants to be a scientist must still study the subject in school (something one suspects that your sci fi fan would find intolerable), or study the life, works, career and writings of a real scientist, such as Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson, African American, who among other things is "interested in the electronic, optical, magnetic and transport properties of novel semiconductor systems” and who is also interested in "quantum dots, mesoscopic systems, and the role of antiferromagnetic fluctuations in correlated 2D electron systems"—I wonder how many winners of the Hugo, Nebula and John W. Campbell Awards (top Science Fiction awards) would even know what she is talking about!

Perhaps they someday a scientist will develop a "mind helmet" that can make someone a scientist in his sleep. Until then most of them will only wonder, "What if—?" And speculative fiction ain’t fiction—good fiction, anyway. For every Ursula K. LeGuin there are hundreds and hundreds of untalented hacks, who write hackwork because they have schooled and immersed themselves in penny-a-word hackwork of their Spec Fiction predecessors instead of good literature. One can tell many of the writers in Dark Matter 2 worship at the altar of Olivia Butler, Tananarive Due and Nalo Hopkinson. As the young folks say, "they cool." But their models were Isaac Asimov and Stephen King and Dean Koontz—fine and successful producers of commercial fiction they may be nobody would confuse them with James Joyce or Henry James. Like commercial artists take for models Boris Vallejo and Frank Frazetta rather than DaVinci, Van Gogh, Dali or Picasso (or Jacob Lawrence, John Biggers or Ronald Herd) they are not going to the source.

New Black writers of speculative fiction should read Delaney, Butler, Barnes, Due, and Hopkinson but should idolize Hurston, Wright, Ellison and Baldwin. As Stephen Barnes himself once advised some writers you should read at least one level above the one at which you want to write. Dark Matter 2 is Black; I’ll give it that. The writers are improvising and extrapolating on African and African American cultural tropes and themes.

I expected, perhaps unfairly, he work of black writers, to paraphrase the ungrammatical introduction of William Shatner to the original Star Trek TV program, "boldly going where no black writers have gone before" to be groundbreaking, life changing; the equivalent of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie birthing Be Bop or the most surreal parts of Native Son, Invisible Man, Beloved all rolled into one.

To send black mind streaking ahead of the Years Best Science Fiction or Year’s Best Fantasy anthologies like Marian Jones at warp speed. To make my soul do the boogaloo on da moon. To at least be straight up scandalous.

Dark Matter 2 was not all that. It was disappointing that Ms. Thomas had to jump in the Wayback to find my favorite story here, Samuel R. Delaney’s excellent "Corona"—a story about a little black girl driven mad by her own telepathic powers—(first published in 1967).

There are good reasons for this. African American speculative fiction is in its infancy. African Americans who write only spec fiction are few, so unlike white collections, that have hundreds of published works from dozens of books and magazines to pick from, Dark Matter 2 had to include works of unproven quality published for the first time, which hurt its overall quality. I can hear now the wailing and gnashing of teeth of some misguided black speculative fiction fans, who ought to get a life, wailing, if Dark Matter 2 does not do well (copies of Dark Matter 1, without doubt a groundbreaking volume, were going at a recent book fair for $2 a pop) that blacks do not "get" it.

They need to, as the young folks say, "take a chill pill". Speculative fiction accounts, at most, for seven percent of book sales. Few people of any race have a desire or a need to "get" it. If we are what we eat, we are what we read. Books are spiritual food, just as one should eat nourishing food one should read books that nourish strengthen the reader. Speculative fiction is escape. Speculative fiction is entertainment. It is candy.

Stimulating candy at times, but just like sugary sweets, it does not stick to the ribs, build strong nourishing spirits. As magic the spec fiction mojo is weak and short-lived. I would here argue that the readers of Sisters Nineties have visited the Physicists of the African Diaspora website, the African Americans in The Sciences website, have read of the lives of George Washington Carver and Lincoln I Digguid, a local black scientist featured in the St. Louis Post Dispatch Wednesday, February 14, 2001.

They have read Mumbo Jumbo, Songs of Enchantment, Love, and All Stories are True. They can see the fantasy of The American Dream or horror in the inner city streets or the television reports from Iraq. They, like the Sankofa bird, know where they have been and where they are going. Whatever there is to "get" without doubt they done already "got" it and gone.

Copyright Chris Hayden 2004 Originally posted on AALBC.com, on Thursday, August 19, 2004 - 10:27 am and was scheduled to appear in Sisters Nineties magazine the follwoing fall.