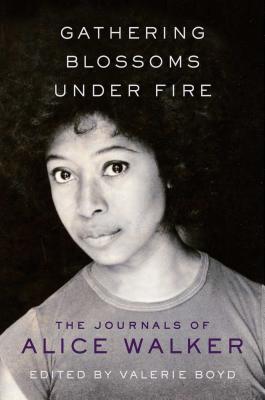

Book Review: Gathering Blossoms Under Fire: The Journals of Alice Walker

Reviewed by:

Robert FlemingNobody will find the controversial writer, Alice Walker neutral, because of her fierce, unorthodox views. As an award-winning novelist, essayist, and poet, she has devoted her gifts to both observing the external and internal worlds. Complied by acclaimed scholar and editor Valerie Boyd, her current book, Gathering Blossoms Under Fire, is a hefty collection of her revealing journals dating from 1965 to 2000.

Her comments to a wary media pinpoint her reasons for their publication at this time: “Part of our responsibility as elders is to share our experience of life with younger people so they don’t have to bump into some of the same boulders that smashed so many of our people in the world.” So many of her generation have turned their back on that responsibility, choosing to coast on their reputation or bankability.

Born on February 9, 1944, in Eatonton, Georgia, Walker was the youngest daughter of poor sharecroppers, with her mother hired out as a maid to support their eight children. An incident occurred when she was eight years old, being struck in the right eye with a BB pellet during playing with two brothers. Her damaged eye seriously affected her, leaving her timid and withdrawn, and she started reading and writing poetry. She was an exceptional student in her segregated schools, using her valedictorian graduation to capture a scholarship to attend Spelman College in Atlanta. From there, she attended Sarah Lawrence up North, where she visited Africa as a student in a study-abroad program. When she graduated in 1965, her publishing career began with her first book of poetry, Once.

Walker’s Gathering Blossoms Under Fire begins in 1965 with her civil rights work, her marriage to a white Jewish lawyer (the first interracial marriage in Mississippi at that time), her motherhood, lust and love, divorce, relationships with men and women, evolving sexual tastes, spirituality, financial woes, colorism, female genital mutilation, Black feminism, and the ups and downs of a public literary icon. Her political and cultural friends and associates fill the pages: Gloria Steinem, Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, Angela Davis, Quincy Jones, Nikki Giovanni, Oprah Winfrey, and many others.

Since Walker started jotting her expansive, complicated life in over sixty-five journals and notebooks, spanning more than five decades, gifting them along with other documents to the archive of Emory University in Atlanta. However, these items will be kept from the public until 2040. In 1970, she published her first novel, The Third Life of Grange Copeland, beginning a career which included the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Color Purple (1982), The Temple of My Familiar (1989), Possessing the Secret of Joy (1992), Complete Stories (1994), The Way Forward is with a Broken Heart (2000), Sent By Earth: A Message from the Grandmother Spirit, After the Bombing of the World Trade Center and Pentagon (2001), and Overcoming Speechlessness: A Poet Encounters the Horror in Rwanda, Eastern Congo and Palestine/Israel (2010), Also, she published nearly a dozen poetry collection. Her writings were translated into two dozen languages and over 15 million copies of her books have been sold.

In the book, journaling becomes magic. It becomes entertaining, and revelatory, exploring the breadth and quality of her memory. Journals done right is an art such as those of authors, Maya Angelou, Thomas Merton, Jerry Stahl, Kathryn Harrison, Martin Amis, and John Edgar Wideman. Walker writes: “What am I really? And what do I want to do with me? Somehow I know I shall never feel settled with myself and life until I have a profession I can love — teaching Dickinson and Donne to crew-cuts would suit me somewhat…One should never give one’s self out of drunkenness, pity, contempt, curiosity only, or passion only.”

Ever the determined campaigner, Walker first met Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. while a student at Spelman College in the early 1960s, with his words compelling her to volunteer for voting rights in the South. She attended the 1963 March on Washington and later ventured to register Black voters in Georgia and Mississippi. In 1983, she coined womanism (a Black feminist or feminist of color) in her collection, In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens. One of her achievements was being appointed a judge member of the Russell Tribune on Palestine, supporting the call to boycott, divestment, and sanctions against Israel. She also supported the movement for peace and justice, animal advocacy, and transgender rights.

As a Black feminist, Walker is conflicted about motherhood and the birth of an interracial child, Rebecca, in 1969. Her journal takes up her ambivalence about the responsibility of parenting: “And what of Rebecca? At least she is the only child I will have. Thank God for that. I will try to do what is best for her — the old cliché. Neither Mel (her husband) nor I should have had a child. We’re equally unready.” Later, she arranged to have tubal ligation surgery, preventing a future pregnancy.

With the birth of her daughter and the decline of her marriage, Walker feels emotionally trapped and alone. She separates from her husband and moves to Brooklyn, still trying to shake off the gloom. “I have had one period of depression in the past two years,” she writes. “Compared to my frequent bouts in Jackson, this is nothing. Only once was bad enough to frighten me.”

She attempts to sort out why her father rejected her sister Mamie and her, concluding that skin color was not the reason, but “her ways” which recalled the patriarch of his mother, who was shot and killed by her lover in a pasture on the way home from church. His mother died in Walker’s father’s arms, a tragedy for a boy at the age of eleven. This is just a chapter in the childhood of the complex life of the author.

Walker is, for the most part, very opinionated, often emotionally guarded, confidently probing every hurt, but protective of her precious soul. During her time in Mississippi, she writes: “There are times, it seems to me, when a little selfishness is warranted. And I admit a creeping growing selfishness. I want to survive. I want to live without choking, without worrying every minute that I’ll be hurt. My feelings are precious, at least to me, and just because other people live enough through vileness and endure doesn’t mean I can or will.”

On writing, she notes: “What always amazes me is knowing I can’t live without writing. Surely this is odd. How my fingers want a pen in them, my hand likes the feel of paper and notebooks.”

Throughout the journal, she praises Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Ernest Gaines, Anais Nin, Jean Toomer, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and the African modern novelists. Following Meridian and The Color Purple, male critics blasted her for her racial and gender politics, including Ishmael Reed’s statement about Walker’s depiction of black men as “rapists.”

Her reply to the wave of criticism goes: “We want freedom. Freedom to be ourselves. To write the unwriteable. To say the unsayable. To think the unthinkable. To dare to engage the world in a conversation it has not had before.”

With the allure of fame and opportunity, Walker turns her back on everything racist, classist, sexist, and otherwise, choosing to select women-loving women. She becomes a sexual adventurer, stressing how she names herself. “For it is important what we call ourselves,” she writes. “The word lesbian is growing on me as I find myself, loving, desiring, and admiring so many lesbians. In fact, the spirit of lesbians is often irresistible….I’ve always liked the sound of gay.”

Despite the confusion of the mainstream moral thought, Walker believes she recognizes God and her divine power. “One day while meditating I felt I knew God exists. That I knew what God is. My God, believing in God! How quaint, old fashioned and cowardly!…God is the inner voice that is always right. God is the universe striving to perfect itself. The devil is the evil in the world & it is gaining on us.”

Alice Walker’s extraordinary journal, this is a document of a shaped life experience created with the skill of a sculptor. It is delivered in a distinctive voice from start to finish. Misunderstood and misinterpreted, the country girl’s existence evolves into a modern celebrity on the big global stage. This journal deserves to be read, both for the novice and veteran writer, especially those seeking calm and grace in the turbulence of career and life.