Book Review: Second Line Home: New Orleans Poems

Reviewed by:

Rudolph LewisJune 2005, almost a decade ago, was the time I last visited New Orleans. It was still almost the Big Easy I knew in the mid-1980s. Several months later the nation observed via television the flooding of the Crescent City—85 percent after levees collapsed. The Lower 9th Ward was devastated and much of the 7th Ward. That is, entire communities and family homes were destroyed and were never to be reoccupied. New Orleans lost 140,845 residents, most of which were black and poor. Maybe the best of New Orleans retreated to cities in Texas, and other sanctuaries east, north, and west—made refugees by government officials. That is, the abandoned poor were not given a choice—they went where they were sent. Other cities provided these impoverished rejects opportunities New Orleans wouldn’t. Only a quarter of the city’s 4,200 public housing units demolished … have been rebuilt” The black population fell from black population fell from 67.3 percent to 60.2 percent. Over a 1,000 were killed by the flooding (David Mildenberg, “Census Finds Hurricane Katrina Left New Orleans Richer, Whiter, Emptier).”

City blocks… smile

Toothless, missing homes now demolished,

Families lost to Gonzales, Vacherie, Houston

Black-lanta and all points out of here

—Mona Lisa Saloy, Sundays in New Orleans

Construction and real estate agencies encouraged Latin “fresh

blood” from Mexico and Central America to come work for them, while

natives of New Orleans were not allowed to return by a collusion of city,

state, and federal agencies—done legally by condemning homes, dynamiting

federal housing projects undamaged and inhabitable, and specious housing

codes which prevented poor residents and homeowners from returning and

rebuilding their family homes. “Obstacles to public funding of

affordable housing came from within New Orleans and in neighboring parishes.

Many in New Orleans do not want the poor who lived in public housing to

return” (Bill Quigley, “Eighteen Months After Katrina”).

In the 1980s (and before) the cost of housing in New Orleans was rather

inexpensive compared to other big cities. The poor lived rather comfortably

in the arms of cultural and familial traditions and look forward to an even

brighter future. Many homes, especially in the 7th and 9th wards had been

passed down from generation to generation. For tens of thousands that future

in New Orleans was drowned. Housing costs soared. According to Jose Torres

Tama

Hard Living in the Big Easy (June 2006), “In the

Marigny neighborhood where I live, downriver and east of the Viuex Carre, a

double shotgun Creole cottage that was worth $120 grand in 2001 was selling

at the hefty speculated value of $240 to $280 thousand dollars.”

All of what was the Big Easy was lost by leaders careless and corrupt in

September 2005. Later, eighteen months after that tragic drama—the flooding

of New Orleans—Jerry W. Ward, Jr. published a literary view of the cosmic

depth and breadth of the grief and loss and the evil that brought on the

flooding in his

The Katrina Papers: A Journal of Trauma and

Recovery (2007). One of Ward’s journal pieces was written as

early as 6 December 2005, titled “Reckoning with Displacement”:

“The disadvantages of forced exile, you can freely lie to yourself, are sweeter and yield higher dividends. Matthew Arnold thought sweetness and light were primal ingredients of the civilized mind. He was dead wrong. The truly civilized mind is a product of recurring darkness. It can not flourish where the dirt is not as saturated with bitter toxins like the soil of post-Katrina New Orleans. Examine the fabulous textures of writers exiled from the Crescent City for evidence. Or explore the weavings of writers who have returned to the Big Easy to create in the moldy stench, in an "exile" from the normal.”

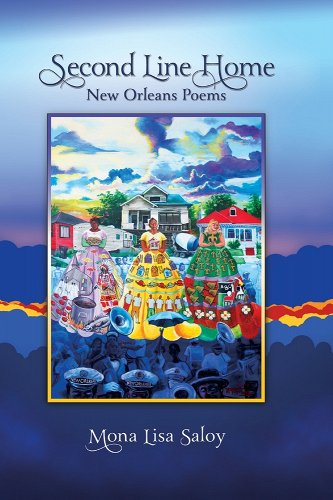

In contrast to Ward’s journal of poems, essays, letters and other materials, Mona Lisa Saloy’s refreshing, Second Line Home (2014) is a poetic memoir of her post-Katrina experiences—from her evacuation with friends and neighborhoods to her return, through efforts to rebuild and reoccupy her 7th Ward home handed down to her by her Black Creole father.

Saloy emphasizes the resilience of Black Creole culture, which she views at the core of New Orleans cultural life. With its central faith, New Orleans, with a little help from her friends, can be as the fabled phoenix bird and live again as it once did before its demise. That is, a fount of cultural creativity. As a teller of tales in the tradition of New Orleans’ excellent oral storytellers, she uses printed verse to mime the voices and intricacies of life lived fully in the Big Easy. Personally blessed with talents and intellectual skills, she too was forced out the city. Nevertheless, Dr. Saloy managed to return to her home city and reestablish her position of professorship at Dillard University. She returned in 2007 after almost two years in Seattle. Still teaching and speaking for New Orleans unique culture, she’s still trying to rebuild her home in 7th Ward New Orleans, nine years later. To do so, the new housing codes required her to demolish her flood-damaged family home: as she reports,

$100,000 cost to elevate it and termite eaten wood

Nixed keeping our family place

(“From Lament to Hope”).

Professor Saloy

is exceptional. Only a select few have had her resources, talents, and

persistence necessary to jump through all the political and legal hoops

necessary to acquire government assistance and loans. Of course, we cannot

underestimate her profound love for the community in which she was born and

raised, as well as thankfulness for her familial inheritance and her desire

to sustain and extol the virtues of that neighborhood life passed down over

the generations.

A story of despair, grief, love, and hope, Second Line Home

contains 54 poems, divided into six sections and slightly over a hundred

pages in length, including “Notes” and a “Glossary.”

Dr. Saloy, a very skilled poet, as well as a local folklorist, captures

Black Creole speech, music, and other cultural aspects of New Orleans

neighborhood life. For instance, the title references the cultural tradition

of a marching band playing after the loved one is buried: neighborhood

folks—family and friends—follow the employed band chanting and dancing. This

procession is called the “second line.” The title used as a

metaphor, this book of poems thus is a kind of celebration. But, as we all

know, a celebration is not without thoughts and memories of the past,

sometimes a very tragic past and present. The book opens with the section

“See You in the Gumbo” (a folk statement of cultural unity)

containing three poems that sketch out and describe what New Orleans is and

the westward traffic-jammed evacuation.

The first poem of the same title characterizes the uniqueness of what is New

Orleans—a place of food, music, dance, celebration, religion

(“venerating saints like Anne, Joseph & saving sinners”). All of

which caused, before the tragic flooding, a derision of fears of a windy and

watery death. The first poem provides background (a prologue) of how the

poor folk of New Orleans dealt with hurricanes before Katrina:

Storm warnings rise like cream in café au lait

Folks don’t make no never mind about

Hurricane season starts, we

Joke about Hurricane Betsy whose waters flowed

Down streets like a parade with

Floating bodies of dogs, cats, people, shrimp, swollen stinky, we

Party, shake off the coat of fear with a DJ spinning Joe Jones’

“You talk too much, you worry me to death….”

Dance like nobody’s there; dance like nobody’s there,

Gas up the car, pack emergency lights, shout

See you in the gumbo! See you in the gumbo!

The next poem “Sankofa NOLA” provides a sketch of the historical background of the multiethnic character of New Orleans, not only its European ethnic groups (English, Irish, French, German, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese) but also from Cuba, Haiti, and Central America, “to carve lives into New Orleans, Caribbean North, into neighborhoods / like Gentilly / Sugar Hill, Treme, Pallet Land …” as well as “Natives Choctaw, Houma, Natchez, and Alabama.” The poem ends with a statement of the unique healing aspects of New Orleans Creole culture. There was

Love always, committed to caring

One family, one block, one church, many Cubans, Haitians, Puerto Rican Creole

Cultures together celebrating each one’s crafts

Teaching each one’s generations grounded in this

Crescent City landscape of camellia, bougainvillea, hydrangea, iris in

‘Sippi & Pontchartrain clay, with swamp, ‘squitoes & sunshine.

Certainly, the clay, the swamp, mosquitoes, and sunshine remain. It’s not so certain that the post-2005 recomposition of New Orleans has the same creative qualities as it was before Katrina. In a manner, the rest of the book—filled with hope and belief in miracles, and political recognition of the significance of New Orleans—asserts the true New Orleans can be reborn. But that hope might indeed be baseless in that politicians and investors have ignored the negative impact of excluding its poor natives and discouraging old neighborhoods from resettlement. According to the 2010 census, the poverty rates have returned to the pre-2005 levels (28 percent in 1999 to 29 percent in 2012). Political decisions that caused the emptying of New Orleans of its poor has not effected the long-term economic opportunities necessary to sustain hope and prevent high crime rates such as those that are generated violent drug trafficking, and other criminal pursuits taken by the poor for mere survival. Empting the Big Easy of its poor thus only had a temporary impact, that is, a poverty rate drop to 21 percent in 2007.

The third poem “Evacuation Blues: This is how we did it” dramatizes the poet’s exodus or path of escape from pre-Katrina New Orleans, and stops along the way.

We were bumper to bumper for hours, the

Sun high over our heads, we waving at cousins in caravan, other

Church folks in contraflow lanes, all traffic fanned akimbo from the

Crescent City praying for safe passage, affirming that

“Nothing can happen that God can’t handle.” Then we sing along with

94.5 FM, the Praise Station blasts Fred Hammond:

“We shall mount up on wings

Like an eagle and soar …

They that wait on the Lord, wait on the Lord …”

Rows of traffic, cars, trucks, in lanes like ants to anywhere safe,

Stopping in lines unable to move 45 minutes at a time, then

Longer, Jasmine happy looking out of the picture window, then

Nightfall outside of Baton Rouge eight hours later, Miz Ruth & I

Dancing in our seat, I

Call Cindy La…

Later in the 2nd section, “Requiem for the Crescent City” the poet speaks more in detail about the multiethnic cooperative character of and relationships in New Orleans in the poem “2 Friends”: Cindy Lou Levee, a middle class Jew from Uptown New Orleans contrasts to Saloy born to a Seventh Ward, downtown working class Catholic Creole father. Despite the differences, they’re for each other in crisis. This example and kind of friendship is one way the Professor Saloy believes New Orleans can be better than it has been. The poem “August Landing & Katrina Hits” again sets the tone of persons working together for the common good, as she and her neighbor take refuge at the house of Cindy & her husband Terry in Baton Rouge. The poet renders a very vivid feel of the impact of the hurricane they endured through the night:

Winds wail through wee hours, bigger branches beat windows,

Rooftops, and bomb doors like a war zone rattling shrapnel, then

lights fail; the television blackens…

No one sleeps. Storm surges sound sprays, breaks windows nearby,

Windows pained by pressure.

We pray in Creole, English, and Hebrew. Papa nou. Our father

Hallelujah

Too scared to talk anymore, silence sends sleep.

Probably the most powerful of these requiem poems is titled “On not being able to write a post-Katrina poem about New Orleans.” Though shorter than and less militant than the notorious “Somebody Blew Up America” by Amiri Baraka, Professor Saloy knows the cause of the flood disaster: the incompetence and corruption of government officials. One possibly may also even speak with conviction of a conspiracy to “bring in new blood” and expel the old, a curative bleeding like pre-20th century medicine. She writes:

It wasn’t Katrina you see

It was the levees

One levee crumbled under Pontchartrain water surges

One levee broke by barge, the one not supposed to park near Ninth

Ward streets

One levee overflowed under Pontchartrain water pressure

We paid for a 17-foot levee but

We got 10-foot levees, so

Who got all that money—the hundred of thousands

Earmarked for the people’s protection…

With the tragic sufferings and horrors of the black poor vivid for all to see, the public masquerade of innocence and government lack of responsibility are challenged. Outraged Saloy compares post-Katrina events to the brutality and cruelty that occurred during the Atlantic slave trade, slavery, and Jim Crow brought with callous self-interest into the Republic by slaveholding White Fathers, like Tom Jefferson, who had no respect for the human worth of black life:

Our poor who without cars cling to interstate ramps like buoys

Our young mothers starving stealing diapers and bottles of baby food

Our families spread as ashes to the wind after cremation

Our brothers our sisters our aunts our uncles our mothers our fathers lost

Stranded like slaves in the Middle Passages

Pressed like sardines, in the Superdome, like in slave ships.

Though there’s no mystery about those responsible for the flooding of New Orleans 2005, the poet ends the poem with a barrage of probing questions how the post-Katrina tragedy could be allowed to happen. After reviewing the bitter images of neglect for the least of us, the Invisible made visible by a media hungry for sensationalized black life they are questions whose answers are filled with mockery, scorn, and sarcasm:

Where is Benjamin Franklin when we need him?

Did we not work hard, pay our taxes, vote our leaders into office?

What happened to life, liberty, and the pursuit of the good?

Oh say. Can you see us America?

Is our bright burning disappointment visible six months later?

Is all we get the baked-on sludge of putrid water, your empty promises?

Where are you America?

Saloy also recalls the barriers—material, legal, and spiritual—preventing residents returning home to New Orleans. The poem “September 2005, New Orleans” begins with the lines: “They said only businesses could come into the city, / First, then residents by zip code. New Orleans is all / Our business, so I went by rent-a-car … / Traffic slowed stacked, like toys, past Causeway / At the 610 Interstate split. Armed GIs in fatigues say: / ‘State your business’.” But even worst to the spirit

Once in the neighborhood, the smell of death

Laced streets, covered in debris along the sidewalks,

Enough room to pass, with some live wires popping,

No sign of anything alive, no birds chirping, no

‘squitoes buzzing, no cats crossing, no dogs running,

No people here, downtown, no cars either, just empty

Silence, so loud, like the dead ghost towns of the Old West.

Still there was a star of hope at Bullet’s Bar on A.P. Tureaud, which

provided ice, food and drinks for those drudging and digging their homes out

from the debris and muck. With such poems in this section, Saloy begins to

reassure her audience that there is a path forward, as in “New Orleans

in January”: “Angel trumpets and night jasmine fragrance dusk /

When the moon rises in eastern skies smiling.”

Though the loss remains prominent and grief subsides, it “scratches

your skin / Till it bleeds all the bottled-/ Up hurt.” In response,

Saloy evokes a martial tone in several poems, including one of her two grief

poems, “Black faces” are “Still at war with American

justice / Just us / Still thirst for peace / And a home.” In her

“New Orleans Broken Not Dead,” a free sonnet, she invokes Harlem

Renaissance poet Claude McKay’s “If We Must Die.” Her poem

ends with the couplet: “Like men and women, bold, we make our pact, /

Pressed to our knees, held down but kicking back!” One would be blind

not to acknowledge the role Race plays in our political decisions. Saloy

points out the “Hundreds of thousands of Iraqis / Crushed into crumbs

/ Their neighborhoods smashed, / Artifacts of humanity looted / Like the

lives of young and old. / The sea is painted with their blood”

(“Iraq by the Numbers”).

Back home in the States, “racism, prejudice, / Walking while Black, /

Glass ceilings, / Brick walls, Emmett Till, / 41 bullets shot at Diallo in

NYC / … Deflated dreams of equality, and / The fact that African

Americans still / Scrape for crumbs of the American pie” (“My

Race”). Though still living with hope of equity, justice, and

progress, Saloy knows that “New Orleans still lies broken”: gas

bills are four times higher, and “rentals four times too”

(“Meanwhile, Back in America”). What may be worst for community

is the generational differences: the carelessness, lack of respect of

wayward youth, those hopeless and dispossessed of chances for the American

Dream: “I wouldn’t be so shocked to find my 100-year-old cypress

doors & windows destroyed, / My cement and bricks—formed by Creole

craftsmen—broken like rotten teeth,” as they slither away (“For

the New Young Bloods on my Porch”). Repression of the black poor not

only has an impact on white fears but also on those of the black

middle-classes. All have been disappointed by black elected officials and

their lack of effectiveness in providing an economy and a social atmosphere

that works for the poor. Too often they have worked for self-interest. That

is, the poor have gotten “black faces in white places”:

“Former New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin was sentenced … to 10 years in

prison for bribery, money laundering and other corruption that spanned his

two terms as mayor—including the chaotic years after Hurricane Katrina hit

in 2005” (Kevin McGill, “10 year sentence for ex-New Orleans

Mayor Nagin”).

Section 3 “La Vie Crĉole & Étoufĉe Talk” contains eleven poems:

2 about Creole foods, e.g., breads and beans; and the rest about family and

neighbors. There are several about Saloy’s Creole dad; and several

about her mom. Both parents have passed—her mom when she was sixteen. One of

those poems is fairly dense. It reports personal difficulties of her Creole

father and his other two wives, the third and last DD. “Some say she

drank herself to death, some say / DD had bourbon with a Coke back for

breakfast most days. Still, / I know better. Grief. / Grief got hold of her

like the left side of bad luck and / Never let go, Finally, / She has

peace.” Hope and grief are locked hand in hand. DD’s “last

daughter” was killed on her way to her senior prom. Like Saloy, she

“wanted college.” (“Creole Daddy Ways”). When her

Creole daddy’s second wife, “Deep, dark chocolate, tall like me,

5’8”, heavy boned, a / Black beauty” (when her mom) died,

Saloy reveals, “my world” was “crushed like smashed

pecans.” That’s a lot of hurt.

Imaginative thinking like poetry writing, indeed, is a special way of

discovering the spiritual beauty in hurt and loss, e.g., courage and

endurance. Such is evident in Saloy’s other poems about her deceased

mother and father. Both are connected to that hundred-year-old Creole house

that was lost and that lovely neighborhood “soaked in the stench of

death” (“December 2005 at Stephanie’s House”). But a

house is not a home, which is a place in which people live—talk, laugh, cry,

and all the other acts that fill life with humor and tragedy. Saloy is the

first poet I know to write two Alzheimer’s poems, or even one such

poem. And she does it well and compassionately: it matches observations of

my grandmother’s behavior during her last post-90 years. The poet in

“The Day Alzheimer’s Showed,” recalls her father’s

early stages when he confuses TV reality (“The Young and

Restless’) with everyday street reality. In “Alzheimer’s,

Day Two,” she paints a lovely portrait of her father (in his 80s) in

mental decline: “Bebé, get the door. / Can’t you hear that

damned doorbell ringing?’ / This Creole crazy man / is my daddy, the /

First man I loved, At whose feet I read the funnies, the dictionary, / At

whose side we read all the jokes in The Reader’s Digest, / At whose

table we searched the / American Peoples Encyclopedia / … His eyes are

gunmetal grey today, and / Stare with questions bouncing eye to eye. /

‘I don’t know who that is, Shut the door’.”

In two other poems, Saloy’s mother meditations are prompted by a

“Sepia photo circa 1943.” The poem “She was not a queen,

but …” focuses on her mother’s “smooth skin, / Burnt

chocolate brown” which was in great contrast to that of her Creole

dad, who appears white in a saved black-and white photo. But it ends

reflectively with the line, “I wipe the mold carefully, / Caress her

eyes with mine / Thankful her photo survives.” In a world that praises

“whiteness,” Saloy suggests that her Creole dad Louie boosted

her mother’s self-confidence rwgarding her dark complexion. The poet

plays on that image—“he was in love, gave her the first taste of

chocolate, the / Color of her cheeks” were a “frame” for

the whiteness of her smile. The poet again returns to her mother’s

eyes, “she liked to wink at me, and I / Melted each time, warmed over

with / Her narrow brown eyes, the color of raw almonds.” In her

“Missing Mother” poem, there’s sadness and reconciliation.

Only “two weeks past 16,” Saloy recalls, “she left me /

Shriveled up like a blue prune, and / Left this life without saying

goodbye.” Maternally abandoned, the poet now realizes she herself is

“older than her last day.” The poet’s personal endurance

and victories have brought some understanding to her mother’s view of

the world and her own mother’s hurt, which resonates as taking her

mother’s advice given during the poet’s childhood: “Today,

from now on, I’m sitting and standing erect / Thankful for the dream

of days and / Mother’s wisdom packed in my pocket.”

The fourth section “Hurricanes & Hallelujahs” presents a newly

post-Katrina attitude by New Orleanians about hurricanes and the hurricane

season. The tragic consequences of the flooding of New Orleans brought an

end to an era that might be referred to as “Laissez le bontemps

rouler” (“Let the good times roll”), when the folks

“dance like nobody’s there” (“See You in the

Gumbo”). The lost of over 100,000 residents, the break up of families

and neighborhoods, the federal neglect, the economic disregard, and an

unkind racial petulance grown among the white middle-classes during the

post-80s era and flamed up in the 21st century. This readily apparent

negation of its black poor brought on a reticence and a watchful

attentiveness toward the warning months of the hurricane season, in which

the people and the city were on the “hit-list target.” In the

interim (2006 to 2012), there was Gustav, Isaac, Irene, and then Sandy. The

poet concludes, “We give thanks for such / Reminders, what’s

important / Being here” (“Hurricane Days”). The people

have been forced to learn truth-telling lessons about callous cruelty. In

the poem “Hurricane Lessons: Isaac September & Sandy October,”

Saloy reminds her readers of the nation’s forgetful sense of history

and appreciation:

Post-Katrina flooding was an unnatural disaster to a

Beautiful city below sea level, a city whose typography

Scoops are the neighborhoods making culture almost four

Centuries old and still warming the world with wonder.

But from all reports, governments near and far from New Orleans have not learned to be generous to “beautiful” people who became victims of natural and “unnatural” disasters. On the whole rather what we have noted is a most stringent lack of generosity to people of the Big Easy, which suffered a mean-spirited denial of humanity.

I am uncertain what to make of the fifth section, “Presidential

Poems,” other than they were written in the post-Katrina period,

sometime between 2006 and 2012. I am almost certain these five poems are

peripheral to the consequences of the “unnatural” flooding of

the Big Easy. They may also provide a lighter, balancing tone to the main

narrative of this poetic memoir. Of these five praise poems, three poems are

about Mr. Obama’s success in the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections.

One poem is about Mr. Lincoln’s two visits to learn “horror

firsthand” (“Lincoln in New Orleans, 1831). Of course, Louisiana

was not the only slave state or even the worst of the slave states. Mr.

Lincoln may had made the visit like millions of others subsequently for the

unique pleasures the Crescent City offers compared to other American cities.

“We, a Poem” written for George H.W. Bush and William J. Clinton

honors their work as presidents. Specifically, what work Saloy had in mind

is rather fuzzy, as she speaks wondrously of American ideals. From my point

of view, I found both presidents a disappointment, especially the presidency

of Bill Clinton, who ushered in “block grants” to states, rather

than money set-asides directly for decaying cities; the man who also

reformed welfare, making it more difficult for poor black women and placing

a target on the backs of black men.. His “three strikes and

you’re out“ expanded the prison industrial complex,

overwhelmingly blackening jails cells nationally. In 2006 Ishmael Reed

published this occasional poem, although other poets had declined the offer

to compose for the Liberty Medal presentation.

It’s not that these are not good well-executed poems, expressing

confidence and belief in American ideals. My problem is that I do not share

the politics of these poems: their sense of American history and their

praise of American ideals, upon which she earlier in other poems heaped

scorn and disappointment. My perspective is that America still makes and

will continue to make war on the black poor, as well as artists and writers.

Thus I cannot sing sentimental praise songs for American progress as

beautifully as Professor Saloy. Many from the left (black and white) are

inclined to think of our black president as a war criminal with respect to

his use of drones in the assassination of two American citizens. Then there

is his role in dismantling the government of Libya and his targeted

assassination of Gaddafi. And much more. Though his elections were ones in

which I cast votes for him and that they are noteworthy historical events,

unlike Professor Saloy, I did not in either instance cheer or cry. Professor

Saloy confesses, “I cried for joy … for the first time in my

life” (“The Night America Elected the First Black

President”). As a journalist I have not only been critic of his

foreign policies but also critic of his domestic policies. But I was not

surprised by his patronizing attitude toward addressing the problems and

issues that most affect poor powerless black men. They who too often are

viewed as criminal and less than human.

Unlike Saloy, I do not see the elections of Mr. Obama as bringing

“America back to democracy” (“God Bless President Obama &

the United States of America”). Curiously Ms. Saloy believes that Mr.

Obama gave America “historic free health care” (“Four More

Years for President Obama”). But we know there is nothing free in this

country. While billionaires stash their profits abroad to avoid paying taxes

for the general welfare, insurance, pharmaceutical companies (the general

medical industry), banks, energy and food industries gouge the poor and the

middle-classes. Though personal achievements, the two successful elections

of Barack Obama did not and could not balance the books for the horrors

visited on the Big Easy. Barack’s elections were a corporate sick

joke, a con job, a popular liberal self-delusion at the expense of the black

poor. One might say his presidency has been more significant and more impact

for Latinos than for poor blacks who make up about 30 percent poverty rate

of our most populous metropolitan centers. Not concern about re-election he

has been more vocal about troubling injustice regard to white violence of

police and private citizens and the drug policies instituted by Bill Clinton

during the 1990s.

The last section contains eleven poems, mostly in praise of New Orleans, and

what it has to offer the nation and the world by its example. One exception

to this worthy praise is the poem “100 Thousand Poets for

Change,” with the chant-like exhortation, “Change yourself /

Change your block / Change your community / Change your city / Change the

World,” first recited at New Orleans Café Istanbul 29 September 2012.

And the other is “From Lament to Hope,” which returns to the

narrative tone of the first four sections, which speaks again of her

childhood home: “Now, a demolished 105-year-old / Treasure bought for

$2,000 on the / GI Bill post-WWII by my / Creole Sergeant Daddy …

.” Unable to hold onto a family heirloom, Saloy had to replace it with

“concrete and steel.” The section concludes with “New

Orleans Matters,” a note of bravado:

We ain’t dying y’all; like roaches

We can’t be buried.

We rise after funerals!

Ever heard of a Second Line?

We live, celebrate lives in beats, songs, and dances.

But there are darker notes that are being song by the lovers of New Orleans,

especially by artists and writers. Listen to how Jose Torres Tama,

complained in 2006 what had happened as a result of real estate speculators

and government officials:

“New Orleans of old as a creative cauldron of bohemian tolerances,

street life, and ritualistic culture, which was known to rise up from the

ground, is a sad postcard of itself. I truly love this city, but in my

twenty-two years of life here, I have never been at such a crossroads,

singing the familiar rock-n-roll Clash anthem of ‘should I stay or

should I go now?’ Even the local newspaper, The Times-Picayune, which

has failed miserably in covering the rental crisis, has used this lyric as

front-page headline to denote the mood of thousands caught in the same

personal debate.

“The tragedy is that I may not have an economical choice to stay and

forge a living when basic shelter is oppressively expensive. New Orleans has

been my poetic muse for half my life, but for numerous artists and working

class residents, it is hard living in the ‘Big Easy’ with

post-Katrina rents as high as the lingering water lines.”

Here is what I wrote in review of Professor Saloy’s first book,

“Red Beans and Ricely Yours” (October 2005).

“The life rendered in these poems will never reconstitute itself after

the 2005 Katrina flood. Thus Saloy’s poetic documentation makes the

book exceedingly more precious, especially for those persons displaced who

lived in such communities as the 7th Ward.”

I’m willing to admit that I may have under-estimated the spirit of

that which is New Orleans. With natives like Professor Saloy, just maybe,

New Orleans can be revived and made into something just as wondrous as the

Big Easy that was murdered September 2005 in cold blood. Just maybe the

genius of its people can gather together all the pieces scattered like ashes

nine years ago and create that which may amaze again and keep the fires of

creativity stoked. Long Live the Big Easy! See y’all in the Gumbo!

Rudolph

Lewis

Rudolph

Lewis

Editor and Founder of ChickenBones: A Journal

Rudolph Lewis (born 1948 in Baltimore, Maryland) was raised by his grandparents

William and Ella Lewis of Jarratt, Virginia—in the Village of Jerusalem. He

attended Creath, No. 5 and later graduated from Central High (Sussex). In 1965.

He left Jarratt 1965 to attend Morgan State College (Baltimore). After hearing

Stokely

Carmichael, Walter Lively, and Bob Moore speak on black responsibility in

Fall 1967, he left Morgan State “to join the Revolution” by working

closely with Bob Moore and Walter Lively from 1968 to about 1972.

Read more about

this trailblazing Brother.