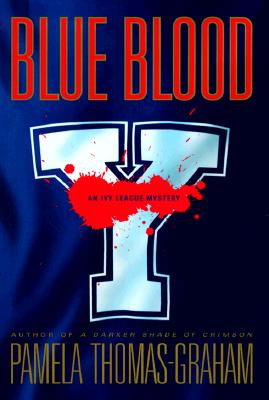

Book Excerpt – Blue Blood (Ivy League Mysteries)

Blue Blood (Ivy League Mysteries)

by Pamela Thomas-Graham

Simon & Schuster (May 05, 1999)

Fiction, Hardcover, 288 pages

More Info ▶

Chapter One: We’re Not in Cambridge Anymore

Georgian. Gothic. Houses. Colleges. The Yard. Old Campus. Widener. Sterling. Finals Clubs. Secret Societies. George Plimpton. William F. Buckley. Conan O’Brien. Dick Cavett. John F. Kennedy. George H. Bush. Shabby chic. Just plain shabby.

The differences between Harvard and Yale are limitless and distinct, and none more important than this: while a Harvard graduate invariably bleeds crimson, at Yale the blood always runs blue.

I jumped into the left lane. But the Buick got there first. So I signaled right and

floored the gas. Anticipating me, the Buick glided back into the right lane and mockingly

flashed its taillights. I pumped hard on my brakes. The Buick slowed down even more. No

jury would have convicted me at that point, so I decided it was time to run him off the

road.

The third Monday of November found me racing down I-95 South on my way from Cambridge, Massachusetts, to New Haven, Connecticut. It was pouring rain, and I was tailgating a dark brown Buick station wagon being driven by a maddeningly oblivious elderly man. I was about to escalate from riding his fender to full-blown light-blinking, horn-blowing, and cursing.

Because I had to get to Yale. Fast. Even though it was too late.

Amanda was already dead.

Finally, the Buick drifted casually into the middle lane and I jetted past, my foot pressing the accelerator so hard that the car doors rattled. My landlady had loaned me her red ’87 Chevy Cavalier for the day, after I’d promised to treat it gently. But there was no gentleness left in the world that morning.

Amanda Fox, the wifthere was nothing that I wouldn’t have done for him.

At least, until the day he announced that he was marrying Amanda Ingersol.

Amanda was the golden girl of my college class: five feet ten, with tawny blond hair, piercing blue eyes, and legs a mile long; she was always suspiciously gorgeous, even at 9:00 A.M. She was fourth-generation Harvard by way of Manhattan, and as a freshman exuded an aura of WASP affluence and bored sophistication that I immediately both loathed and envied. It became clear to me during my first week in Cambridge that being from the Midwest was second only to hailing from the South in inspiring disdain and pity from the likes of Amanda and her Upper East Side, private-school crowd — and being treated like a bumpkin tended to make me testy. My irritation bordered on the homicidal after an episode at a black-tie dinner in the Master’s Residence our sophomore year. "Nikki," she’d called out to me as I sat between a Dean and a visiting scholar from Oxford, struggling to eat my first lobster, "I wish I had a video camera. It’s so refreshing to see someone attack their food with such childlike innocence."

Since Amanda lived in Dunster House, it was impossible to ignore her, although it would have been difficult in any case, given her penchant for striding around campus with a three-quarter-length raccoon coat tossed over her shoulders. ("It was my grandmother’s at Smith," she’d explain.) She managed to infuriate almost every woman I knew, usually as a result of her irritating ability to fascinate every male with whom she came into contact. My differences with her, however, went well beyond minor skirmishes over boys: she was madly conservative politically, which in my book i s the one truly unforgivable sin. As the editor-in-chief of The Salient, the Republican rag on campus, Amanda wrote more than one editorial about affirmative action that nearly brought us to blows. Conveniently ignoring the fact that as an alumni child she herself had received preferential treatment from the admissions office, she openly derided the university’s desire for diversity in the incoming class and once actually challenged me to reveal my SAT scores during a particularly heated argument. By graduation day, I hated her with the kind of passion that only a twenty-one-year-old can muster, but took consolation in knowing that soon I’d be rid of her. And then Gary announced that he was marrying her.

Calling this news earth-shattering would grossly understate its impact. I felt utterly betrayed. As far as I knew, Amanda and Gary had never exchanged more than casual greetings in the dining room. He had never said a word about her to me. And now they were getting married? Everyone had assumed that Amanda either would return to New York and become a Republican-party fund-raiser, or move to DC and disappear into some far-right yahoo congressman’s staff. Either way, we figured that in three or four years, she’d have married a man twice her age and be living on Park Avenue or ensconced in a town house in Georgetown. But instead, there she was, standing beside Gary in the Dunster courtyard, sweetly proclaiming that they were moving to New Haven, that Gary had an exciting opportunity at Yale, that she would be entering Yale Law School, that her aim was to become a law professor. A professor!

Why would a budding politico such as she take up with an impecunious academic? And how could he do this to me? Gary was my friend, my father-confessor. Not her secret lover.

They were married in a very small ceremony at Cambridge City Hall three days later.

Silence prevailed between Gary and me for almost two years afterward.

But then I stumbled across him in a New Haven pizzeria while on a road trip to the annual Harvard-Yale Game, and somehow all of my anger and resentment suddenly seemed very distant and petty, and I was instantly reminded of how much I missed his friendship. Soon we fell into the routine of regular phone calls and an annual rendezvous at The Game. Whenever we spoke, it was like picking up the last conversation in midstream, and I luxuriated in the warmth of an old, stimulating friendship that had been renewed.

Of Amanda, we spoke very little. I knew that she was becoming very well known and highly controversial. She’d clerked for the most conservative Supreme Court Justice after graduating from Yale Law, and had networked her way around Washington so well that she was publishing a steady stream of op-ed pieces in the far-right press in addition to her legal writing and had regular gigs as a substitute for the major conservative commentators on the Sunday-morning talk shows. I read an article that referred to her success as the "talking dog" syndrome — a beautiful, smart, truly conservative woman being as rare as a canine who can speak. My feeling is that just because a dog can talk doesn’t mean that it should be listened to, but apparently her shtick of rabid conservatism plus her shiny blond hair had mass appeal. The Beltway crowd certainly couldn’t get enough of it. The grapevine had it that she was in DC as often as she was in New Haven, a nd that she was being considered for early tenure, given her growing national stature. Meanwhile, Gary’s career had taken off just as rapidly: he was made a Dean at Yale in record time, and the rumor was that he was actually on track to be the next President of the university. I still had never figured out how he and Amanda came to be married, but they were a true "power couple" in academic circles, and our few mutual friends reported that they seemed blissfully happy — a state far more exalted than any I had ever achieved in a relationship, which, of course, made me dislike Amanda even more.

And now she was dead, at age thirty. It didn’t seem possible.

The sight of the exit off I-95 for downtown New Haven yanked me out of my reverie. Despite the rain I had made excellent time, shaving half an hour off the normally two-hour trip. I cut across two lanes and careened off Exit 47, steering with one hand while I fumbled in my purse for the slip of paper on which I had scribbled directions to Gary’s campus apartment. Take the 3rd exit off the Connector, it read. Then right on…some street that I couldn’t make out, even though it was my handwriting.

Damn.

What had Gary said? I’d been no more than half awake during our conversation, and it showed in my scrawl. The street name looked like a four-letter word ending in "k." Given my current irritation, I could think of at least one word fitting that description, but I doubted that was the name of the street.

Looking up as an exit ramp whizzed by, I wondered uneasily if I had just missed my turnoff. Despite my biannual trips to The Game, New Haven was totally foreign to me, and given the town’s less than savory reputation, I wa sn’t keen on getting lost. Never mind that I had grown up in Detroit and seen more than my fair share of rough urban neighborhoods. Even I was intimidated by the specter of New Haven. Especially after Amanda’s murder. Everyone I knew, including native New Yorkers, said it wasn’t safe. I forcibly resisted the urge to snap the door locks shut as I eyed the burned-out buildings lining either side of the overpass. That was what a timid suburban housewife would do, and I fancied myself a fearless black urbanite. Trailing clouds of bravado, I turned off at the next exit ramp.

I was immediately plunged into a neighborhood of dreary wood-frame houses, most of them covered in peeling pastel paint. The lashing rain had slowed to a steady downpour, and the narrow streets were gloomy and desolate. A small black child opened the front door of a dilapidated house, staring at me as I slowed down to look for a street sign. The ferocity of his expression startled and saddened me, so much so that I rolled through the next intersection without really registering the name of the cross street. Half of the next block was cordoned off with sodden yellow "crime scene" tape, and I could see two white men in dark slickers hunched over the sidewalk inside the barrier, with what appeared to be tape measures in their hands. A cluster of black men huddled inside a bus shelter on the next corner, their breath visible in the icy air. Craning my neck to see the street sign, I floored the accelerator. OLIVE STREET, the sign read. No luck.

That was when I saw the flashing lights in my rearview mirror.

Just what I needed. A policeman on my tail.

Slowly, I pulled over to the side of the street, fighting a rising tide of impatie nce and apprehension as a silver Ford Crown Victoria came to an abrupt halt behind me. Despite a recent successful collaboration with the Harvard cops, I hadn’t shaken my instinctive mistrust of the police. I had plenty of male relatives, and I’d gritted my teeth through a heart-wrenching array of stories of official intimidation and abuse. A black activist had recently coined a phrase for the only crime any of them had committed: "DWB." Driving While Black. After rolling down the window, I carefully placed my hands on top of the steering wheel. Things were bad enough without some trigger-happy cop turning me into a statistic.

It was just as I’d feared: the patrolman was stout, white, and unsmiling. Rain streamed off his navy blue New Haven Police poncho as he stood beside the car. I caught the name Timothy Heaney as he flashed his badge.

"License," he barked.

"Just a minute," I snapped back, fumbling in my purse. "What’s the problem?"

"What do you think? I just clocked you at forty-five in a twenty-five-mile-an-hour zone. Registration."

Registration? Great. Where did Maggie keep it?

I smiled my best shit-eating grin. I was going to have to get this guy on my side fast, before he arrested me for stealing the car. "You know, Officer Heaney, you’re going to have to give me a minute to find it. I borrowed a friend’s car this morning, and I think she probably keeps it in the glove compartment — "

"Uh-huh." He cut me off. "Step out of the car."

"All right," I said pleasantly, between gritted teeth. Would he be searching my car if I were a cute little blond girl? I thought not.

Moving deliberately, I slid out of the Chevy, my blood pressure spiking up another few po ints as the cold rain hit me full in the face. I pulled up the hood of my yellow slicker, then watched while he rummaged through the glove compartment and emerged with a tattered piece of white paper.

"What’s the friend’s name?" he grunted.

"Magnolia Dailey, 25 Shepard Street in Cambridge, Mass," I said impatiently.

"Fine," he said, nodding impassively. "Get back in the car."

Neanderthal, I fumed. A great big man, bossing around a defenseless, lost woman.

"You’re getting one summons, Miss — Chase," he said, squinting at my driver’s license. "Although this inspection sticker is out of date, too."

"Damn, that’s awfully nice of you."

"You want another ticket, Miss Chase? Because I’d be happy to write it." He leaned closer to the window for emphasis. "This is a residential neighborhood, and there are a lot of little kids on these streets. They should be in school, but some of them aren’t. With all these leaves on top of a slick road, you could’ve killed someone racing through here like that."

Our eyes met. I hate being lectured, and the fact that he was right did nothing to mitigate my intense annoyance. I considered trying to defend myself. But I had broken all laws human and divine on I-95 trying to get to Gary, and I didn’t have time to convince this cop that if I was speeding, it was for a good reason.

I took a deep breath. "Sorry, Officer," I said briskly. "What I meant to say was thank you for not issuing a ticket on the inspection, too. I’ll get it taken care of as soon as I get home." Which couldn’t be soon enough.

"Get used to our speed limit, Miss Chase," the cop said grimly as he handed me the ticket. "You’re not in Cambridge anymore."

Cursing violentl y under my breath, I drove a few more blocks and then got directions to

the campus from a toothless, elderly black man who was standing in the midst of traffic

hawking copies of the New Haven Register. He pointed me toward York Street — which turned

out to be the mystery scrawl on my sheet of directions — and I followed it to Chapel

Street, which was where Gary said I should park. The rain began to slack off as I threw

the car into a space on the street and set out warily on foot.

New Haven was seriously depressing me, and the dilapidated storefronts, empty restaurants, and deserted sidewalks that I was passing weren’t helping. Fully half of the buildings had been abandoned, and their windows bore printed and hand-lettered signs proclaiming SPACE FOR RENT. A hotel advertised "Single Room — $29." Blue and red graffiti scrawls marred several of the storefronts. The awning over a small deli valiantly proclaimed "Fresh Salad Bar," but when I peered through the rain-spattered glass, I saw no occupants save a lone Asian counterman. The place had an air of defeated resignation, as if the worst had already happened, and all that remained was to survive. These Yalies were crazy. Why would anyone in their right mind voluntarily spend four years in this place?

My dispirited mood lasted until a sign proclaiming High Street loomed over my head and I turned left.

And saw before me a vista that seemed at first like a mirage.

Through an immense stone archway I could see a narrow, tree-lined street, which swept past towering slate gray stone Gothic buildings on either side. Stately turrets and chimneys wreathed in fog were faintly visible in the distance, and a majestic stone clock tower with lacy filigrees presided imperiously over the lesser buildings. Where there had been deserted sidewalks, now there were students walking resolutely, carrying books and backpacks, and the very air was misty, and hushed, and contemplative. It was as if Carcassonne, the medieval French walled city, had been transported intact to Connecticut.

I walked slowly down High Street, past brooding stone buildings with moats and arched gateways, and paused at the center of the block. I still had no idea where I was, but I wasn’t minding quite so much now. On my right was a large grassy quadrangle surrounded by lofty brown and gray stone buildings that I knew was Old Campus, where the freshmen lived. That much I remembered from road trips to The Game. But what intrigued me more was across the street. Under the imposing stone clock tower was a slate archway guarded by an ornate wrought-iron gate, through which I could see a large courtyard enveloped in gray mist. Surrounded by stately Gothic buildings, it was beautifully landscaped with weeping willows, maples, and shrubbery. Above the archway was carved an inscription: FOR GOD, FOR COUNTRY, AND FOR YALE.

The lure of the courtyard was irresistible. I crossed the street and gently pulled one of the gate’s large round iron handles, but it was locked. Disappointed, I glanced down at my watch. It was almost noon. I had to find Gary.

"Excuse me," I asked a tall, lanky redheaded man walking past me. He was wearing a Yale sweatshirt underneath his windbreaker, and looked as if he knew where he was going. "Do you know where Branford College is?"

"You’re looking at it. Right through that gate." He gestured. "But it’s cursed." He frowned.

Despite myself, I recoiled from the gate as if it had become electrified. None of us needed any more bad luck.

"The legend is that if you pass through that gate before Commencement, you won’t graduate," he said, grinning at me. "Come on. I’ll show you the main entrance."

We walked back a few feet, and then turned onto a flagstone walkway flanked by Gothic stone buildings on either side. Over a gateway on the left, I read the words JONATHAN EDWARDS. I recognized the name as one of the residential Colleges.

"This is Branford," he said, gesturing to the building on the right. "Here." A ponytailed girl was just opening a heavy wooden door that appeared to be the dorm’s main entrance, so I ran a few steps and grabbed it, shouting my thanks over my shoulder.

I was immediately plunged into a narrow, dimly lit, arched corridor that quickly opened onto a small courtyard. A towering elm stood at its center, encircled by a stone bench. Beyond the courtyard was another narrow corridor, this one with a painted wooden map of Branford College on the wall. I located the room marked DEAN’S APARTMENT. That would be Gary’s. Shaking the rain from my hood, I passed through the corridor and found myself in the large, verdant courtyard that I had originally seen through the forbidden gate.

It was every bit as beautiful as it had seemed from outside, a medieval cloister in the heart of a decaying city. From this vantage point, I could see the intricate details of the beige and gray stone Gothic buildings that surrounded the courtyard. The tall leaded-glass windows glittered, even in the cold, gray mist, and the profusion of trees and low bushes softened what would otherwise have felt harshly monastic. Two wooden benches nestled invitingly unde r a tree, and a wooden swing hung whimsically from a towering oak on the far side of the courtyard.

A wailing police siren from the street outside broke the almost holy stillness, and I turned abruptly toward an arched wooden entry door marked "784-788." That was where I’d find the Dean’s apartment. I peeled off my raincoat as I climbed three flights of well-worn, narrow, circular stone stairs, pausing to look through the thick leaded windows at the courtyard below. I was high enough now to see the maroon, green, and charcoal gray roof tiles of the building’s adjacent wings, and the sharp contrast between the homespun redbrick of Harvard’s dorms and the somber stone stateliness of Yale’s was becoming increasingly apparent. At its heart, Harvard’s campus exuded an all-American simplicity, functionality, and optimism, whereas this place, in its soul, seemed quintessentially European: sophisticated, ornate, and world-weary.

On the third-floor landing, I arrived at a heavy arched wooden door marked DEAN. Gary Fox opened the door on the first knock, and we regarded each other wordlessly for what felt like an eternity. It had been almost exactly a year since I had last seen him, and he looked much the worse for wear. His face was a great deal thinner, making his large gray eyes even more striking, and his shiny black hair was much more liberally sprinkled with silver. He looked tousled and unkempt, as if he hadn’t slept for days.

"Oh, Gary." I breathed slowly. "I’m so sorry."

My jacket slipped to the floor, and then we were holding each other, and I felt sobs racking his body. Sadness shuddered through me in waves, and I held him tighter, absorbing the blows. The persistent feeling of unreality th at had shadowed me all morning slipped away. This was real. She was dead. Just like that.

"Come in, Nikki," he said finally, removing his glasses and wiping his eyes with the back of his hand. "You’re soaking wet. You must be freezing. Come on in."

The suite was surprisingly large: the spacious living room had a dark hardwood floor covered by a faded Oriental rug; there was a low beamed ceiling, and a row of tall leaded-glass windows overlooked the courtyard. I could see three additional rooms beyond heavy oak door frames. I instinctively moved toward the large stone fireplace before I realized that the grate was cold and full of ashes. I was freezing, and it was going to take more than a fire to make me feel warm again. Gary watched me as he stood awkwardly in the middle of the room.

"I hope you’re not going to be in trouble for missing your lectures today."

"Don’t be silly," I chided, glancing around the room. A single lamp burned in what was otherwise an oppressive gloom. "That’s what teaching assistants are for."

"Do you want something to drink, or — " His voice trailed off.

"No, I’m fine." I purposefully turned back toward him. I had come here to comfort him, and it was high time I started. "Come on, let’s sit down."

He sank into the brown leather sofa adjacent to the fireplace, and I sat beside him. Turning to face him, I gently laid my hand on his arm. "Tell me everything." He’d been practically hysterical when he’d called earlier that morning, and my grogginess had only made it harder to understand exactly what had happened.

He took a long breath, and then began speaking. "It all started because she was teaching last night."

"On a Sunday night?"

"Yes, she taught a n undergraduate seminar on the Constitution. Fifteen students." In contrast to his tone of urgency earlier that morning, his voice now sounded dispassionate and almost aloof, as if he were telling someone else’s story, not his own. "The seminar was in a classroom up on Science Hill. In the Klein Biology Building. It ended at about nine-fifteen."

"And did she leave when all the students left?"

"No." He shook his head. "The police told me that someone in the class said that she stayed behind to talk to one of her students. A kid named Marcellus Tyler. They questioned him this morning, and he says he didn’t walk out with her. He claims that they talked for about ten minutes about a paper he was writing for the class, and then he left the building. He said she was packing up to leave, but she had to use the ladies’ room or something. At any rate, he says she told him to go ahead, that she’d be fine. And no one seems to have seen her after that until…"

He paused for a moment and swallowed hard. "They found her body around one o’clock this morning. In the middle of a poor black neighborhood about a half a mile from Klein." He looked at me. "She was stabbed. At least five times. She was covered in blood when they found her, and her hand — her left hand was severed at the wrist."

He had told me that much over the phone when he called that morning, and I still felt nauseated at the thought of so vicious an attack. Who on earth would do such a thing?

"They don’t know yet — " he continued, sounding anguished. "They don’t know if she was raped."

"Do they have any suspects?" I asked.

He nodded slowly, and I felt my heart breaking for him. "This student, Marcellus Tyler. He was the last one to s ee her alive."

"Do you know anything about him?"

Gary shook his head. "I don’t have much information. I think the police said he was a sophomore. I know he must be a big guy, because they said he’s a linebacker on the football team. Oh, and he’s black."

Holy shit.

Amanda was found dead in the middle of a poor black neighborhood, and the last person to see her alive was a black Yale student? Gary really did need me. He was sitting on a racial powder keg.

"I hope you’re not automatically assuming he did it."

"I don’t know, Nikki." He sighed distractedly, raking his fingers through his hair. "I really don’t."

Please don’t let a black man have killed this girl. "I’m just thinking about what his motive could possibly have been," I prodded. "He was her student, right? So why would he want to kill her? Had she just given him a bad grade or something?"

"I don’t know," he repeated numbly. "I just hope to God they find the son of a bitch who did it. Because if it’s not this kid, then it means the killer is still out there."

A gust of wind rattled the windows. "What was the weather like last night?" I asked.

Gary looked at me quizzically. "It was raining. Hard. Why?"

"I was just thinking that it seems more likely that since the weather was bad, it was someone specifically out to get her. No random criminal would be out on the street if last night was anything like it is today. Bad guys hate to be cold and wet, same as the rest of us."

He stared at me. "That’s exactly what the policeman said."

"Don’t mind me. I seem to be channeling Nancy Drew these days." I shrugged lightly, my eyes searching his face.

There was something he wasn’t telling me.

"Gary, are there any other suspects?"

"Yes," he sighed heavily. "There’s one more."

He rose and looked out onto the enchanted courtyard before he turned back to me. "Some of the cops seem to think that I was the one who killed her."

Read Simon & Schuster’s description of Blue Blood (Ivy League Mysteries).

Copyright © 1999 Simon & Schuster, Inc./Pamela Thomas-Graham No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher or author. The format of this excerpt has been modified for presentation here.