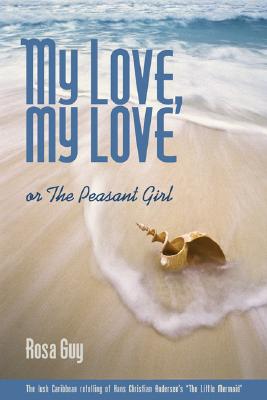

Book Excerpt – My Love, My Love: or The Peasant Girl

My Love, My Love: or The Peasant Girl

by Rosa Guy

List Price: $13.95Coffee House Press (Sep 01, 2002)

Fiction, Paperback, 168 pages

More Info ▶

Chapter One

On that island where rivers run deep, where the sea sparkling in the sun earns it the name Jewel of the Antilles, the tops of the mountains are bare. Ugly scrub brush clings to the sides of their gray stones, giving the peaks a grim aspect that angers the gods and keeps them forever fighting. These terrible battles of the gods affect the lives of all the islanders, rich and poor. But the wealthy in towns, protected from the excesses of the gods’ furies, claim to be masters of their own destiny. The peasants accept the will of the gods as theirs. They pray to the gods when times are hard and give thanks to them when life goes well.

But then the peasants live in the valleys and mountain villages amid flamboyants, poinsettias, azaleas, ficus, eucalyptus, and magnolias-their colors raging over the countryside and blending roads into hills, hills into forests. Multicolored flora defy the destructiveness of man and climate to spring eternally back to life. This miracle the peasants attribute to the gods.

On this island of mountains, forests, hills, and valleys is a lovely peasant village. Huts and wooden frame houses cling to the hillside and nestle on the flatlands of the forest. As in most of the poor villages of the island, each hut stands in its own field on a plot offorested land deeded to the peasants at an earlier time. Trees in the woods surrounding each clearing add fruit to the legumes the peasants must cultivate for their survival. It makes for a very meager existence. But to these gentle people it might seem a paradise, were they not always victims of the whims of gods-and man.

"Once upon a time," said Monsieur Bienconnu, the village centenarian, "the mountains of this Jewel of the Antilles were thick with hardwood trees. The hardest in all the world. Trees reached up from the mountaintops to touch the heavens. They excited the senses and challenged the genius of our men.

"Asaka, goddess of earth, of plants, of all growing things, how generous was her bounty then. She pushed a wilderness of herbs, of bush to thicken the underbrush, keeping the trees forever green, forever productive.

"We peasants worshipped her. Our praise of her rang through the valleys, up through the hills, and on to the mountaintops. With our drums, our songs, we gave her thanks. Our well-being was woven into the fabric of abundance. Asaka smiled and we laughed with joy. She laughed and we danced-forever in one fraternal embrace …"

M. Bienconnu gazed out over the heads of the old couple and the peasant girl working their field. He stared out, looking back in time.

"Agwe, god of the sea, of our many waters-how gentle he was then. How tenderly he treated the voluptuous Asaka. He adored her. Agwe’s caresses nourished the fruits of her work, and rained gently down on us, his benediction, the benediction of the gods."

Mama Euralie and Tonton Julian kept their heads bent over their work. They had been raking through the dry, parched earth since early morning. Now the sun was at its height. They had no patience for the tales of old men, which they knew all too well.

But the peasant girl listened. She stopped her work to gaze up at the mountains. Their bare peaks shone in the bright light of the noonday sun. She imagined them as they had once appeared-fertile, thick with trees, and green-a green that blended them in with the descending hills. Green, green hills, vibrant, intense-a reminder of what this Jewel of the Antilles must once have been.

"Men, men, men, foolish men." M. Bienconnu stood up. The rock on which he had been sitting had once been jagged but was now rubbed smooth, through years of his daily visits. "Foolish men, what disaster they court with their greed. Cutting down our trees-our god-given gifts-and selling them for gain. Stripping Asaka of her riches and giving nothing back. Nothing. Do you wonder that Asaka sulks? Do you wonder that she treats us with indifference? And Agwe, your god of waters-how he punishes her. And what abuse he heaps upon us." The old man moved stiffly across the beaten path to the woods that screened the old couple’s plot from that of their neighbors. "Men" he grumbled. "Their greed will be the destruction of us."

Mama Euralie lifted her head, her bright eyes impish in her wrinkled black face. "We peasants, too, need the charcoal that the wood brings to cook our food."

The old man had disappeared through the woods, but his answer floated back. "Oui, oui, they sold their souls for a few pieces of silver. Ours, too."

Tonton Julian waited until M. Bienconnu was well out of hearing. Then he stopped working to say, "Whatever, we need rain now-now." He bent and scooped up a handful of soil. It ran through his fingers like sand. "Another week without rain, and it might well be the end of us poor peasants."

"It will rain soon," Mama Euralie said. She sniffed the air. "A day or so … a week at the most, oui. It’s on its way."

"Is that your old bones talking?" Tonton Julian asked his wife. "Or did Agwe come and whisper in your ear? If so, how much rain? How little?" He waved her silent with gnarled hands. "Never mind. Too little rain will not help this drought. Too much will wash away the soil. And there you are-your gods making playthings of us poor peasants."

"Mon Dieu, but you blaspheme, Monsieur Julian," the little woman scolded. She looked up at her thin, lanky husband. "Have faith. The gods have never abandoned us yet-neither the gods of our fathers nor the One who rules over them."

"Old woman," Tonton Julian growled, throwing wide his arms and looking over their parched lot of land. "You see life through eyes already dead."

The peasant girl stopped raking through the sandy soil and smiled. The banter between the old couple amused her. Tonton Julian saw her smiling and smiled too, exposing his two remaining teeth. Then he walked toward his old mule tied to the post behind their mud hut, touching the peasant girl gently on her head as he passed. She followed his movements-his bony thighs that showed through the flapping tear of his ragged pants as he walked, the dry skin of his feet as he swung his long frame onto his mule. She liked the way he adjusted his straw hat to keep the open crown away from the top of his head.

Then she stopped seeing; a car was racing past on the distant road.

She strained, listening to the fading sound of its engine. Her eyes were alert, shining. A car. A car. From what unknown place had it come? To what strange place was it going? Oh, to be flying against the wind in a car. To be rushing off to a city, a town …

The old woman sounded a note of warning at the girl’s excitement. "Ti Moune?" She affectionately used the title given to orphans who roamed the countryside. "Dreaming again? About what. Tell me."

Instead of answering, the peasant girl bowed her head and pretended to be absorbed in searching the dry earth for seeds, for bits of legumes they might have overlooked at another time. Her constant daydreaming, the way her eyes looked into space, upset her guardian. The peasant girl tried hard not to daydream when Mama Euralie was around her. Impossible. She sighed.

They worked in silence, raking through the dry earth, searching for carrots, turnips, sweet potatoes, or any addition to the small mounds of vegetables already culled to await the discerning eyes of road vendors. Puny? True. Dry? True. But during these hard times when peasants were reduced to eating only millet or cornbread cereal, even vegetables of poor quality were better than none at all.

Squinting from the glare of the midday sun, which reached through her thick, crisp hair to burn her scalp, the peasant girl walked with her toes curled away from the hot earth over to the bucket of water in the shade of a nearby tree. She dipped a gourdful and took it over to Mama Euralie. The old woman drank some. The peasant girl drank the rest. She took the gourd back to the bucket and stood looking at the tree leaves. They had curled from lack of moisture and awaited but one spark to go up in flames.

Oh, for rain. But a soft, gentle rainfall, not an angry storm of the kind that Agwe sometimes unleashed to devastate fields, flood roads, and sweep everything out to sea. That happened when, in his erratic behavior, Agwe chose to punish the ailing Asaka, blaming her laziness for all the ills visited on poor peasants. At these times, some believed that Agwe had gone mad.

Sighing again-for she often sighed-the peasant girl was turning away from the dry tree when a papillon lit on one of the curling leaves. Slowly she reached out her right hand. With her left hand she held to her shoulder an imaginary cage. Softly she put her hand around the butterfly. It fluttered in its enclosure. The peasant girl closed her eyes. Then, bringing the papillon to the cage on her shoulder, she opened her hand to release it. When she opened her eyes the butterfly had disappeared.

The old woman laughed. "If it’s for rain you wish, pray the cage is not too crammed full of all your other wishes. Even so, force that papillon to squeeze in good. Rainfall this second will not be a second too soon-for me, for this earth, for your poor Tonton Julian." She wiped her parched mouth and turned to gaze warmly at the parting in the woods where the man and his mule had gone, heading toward the road.

The peasant girl blushed. She no longer knew what she had wished for. Had it been for rain? Or had her wish to do with the car that had just gone by? More and more her wishes, dreams-day and night-were tangled. She no longer knew where one began or the other ended.

It was the same when late that afternoon she walked through the woods on her way to the brook. She stopped to greet peasants still working the clearings behind their huts. She talked to them and listened, but once she had passed, she didn’t remember a word that had been said.

When she came to the road, her mind became alert. She stood waiting for a car to go by. None did. Only camionettes bringing market people from marketplaces to their homes. Crossing the road, she kept on up the hill, stopping only when she came to the barbed wire fence that surrounded the Galimar estate. She looked through the fence at the men who worked for Monsieur Galimar from sunup to sundown. Most of the young men of the village worked for M. Galimar.

She stood studying them as they worked, digging into the rich earth of the fields that extended for miles and miles. They resembled carvings she had once seen in a marketplace-beautiful, mahogany brown skin stretched over broad backs, strongly muscled thighs and buttocks glistening with sweat through the openings of their tattered clothes, hats pulled low over their brows to protect their heads.

As the men dug, children romped, their bellies distended, plump, bare buttocks dusty from the rich soil of the fields, while mothers squatted between rows to gather the legumes that their menfolk unearthed, and which drivers of camionettes took into the markets in the big city.

Nor were these puny legumes. They were big, fat vegetables formed with the richness that moisture and good soil produced. On the Galimar estate, water was saved in giant tanks during rainy season, for use during the dry season or times of drought. But then, M. Galimar was a "grand homme."

Like most grands hommes, M. Galimar lived in a big city, far away from the lands that bore his name, and sent his children abroad to school. The peasant girl had heard that M. Galimar had a daughter her age, and that he sent her across the sea.

The girl had seen the great man once. One day on the road he had stopped his big, shining car to show off his land to his companions (tourists, it had been whispered). They had stopped for only a few minutes-long enough to attract dozens of peasants-then they had gone, flying off toward the grand ville.

How excited she had been! The look of the man, his car, his companions, had filled her with wild visions of unknown places.

She had asked Tonton Julian, "Are there no poor people living in the grand villes?"

"No poor!" the irascible man had bellowed. "If there were no poor, how do you think rich men would live?"

Despite Tonton Julian’s scorn, the peasant girl had liked the gentle look of the tall, smooth-faced, tan-skinned mulatto with his straight hair. Many of the papillons she had captured and held since that day had had a vague wish attached: one day … one day …

Mama Euralie, always so concerned about what the peasant girl might be thinking, would often see the wistful way she looked at the productive fields of M. Galimar and mistake her longing for jealousy. "Ti Moune," she admonished, "there are many worse off than we, oui."

And that was true.

Read Coffee House Press’s description of My Love, My Love: or The Peasant Girl.

Copyright © 2002 Coffee House Press/Rosa Guy No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher or author. The format of this excerpt has been modified for presentation here.