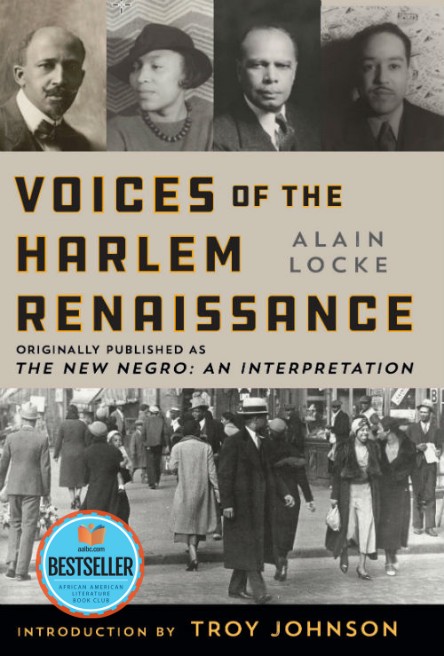

Voices of the Harlem Renaissance: Originally Published as The New Negro an Interpretation

Excerpt

“Harlem” by Alain Locke

If we were to offer a symbol of what Harlem has come to mean in the short span of twenty years it would be another statue of liberty on the landward side of New York. It stands for a folk-movement which in human significance can be compared only with the pushing back of the western frontier in the first half of the last century, or the waves of immigration which have swept in from overseas in the last half. Numerically far smaller than either of these movements, the volume of migration is such none the less that Harlem has become the greatest Negro community the world has known—without counterpart in the South or in Africa. But beyond this, Harlem represents the Negro’s latest thrust towards Democracy.

The special significance that today stamps it as the sign and center

of the renaissance of a people lies, however, layers deep under the Harlem that many know

but few have begun to understand. Physically Harlem is little more than a note of sharper

color in the kaleidoscope of New York. The metropolis pays little heed to the shifting

crystallizations of its own heterogeneous millions. Never having experienced permanence,

it has watched, without emotion or even curiosity, Irish, Jew, Italian, Negro, a score of

other races drift in and out of the same colorless tenements.

So Harlem has come into being and grasped its destiny with little heed from New York. And

to the herded thousands who shoot beneath it twice a day on the subway, or the

comparatively few whose daily travel takes them within sight of its fringes or down its

main arteries, it is a black belt and nothing more. The pattern of delicatessen store and

cigar shop and restaurant and undertaker’s shop which repeats itself a thousand times on

each of New York’s long avenues is unbroken through Harlem. Its apartments, churches and

storefronts antedated the Negroes and, for all New York knows, may outlast them there. For

most of New York, Harlem is merely a rough rectangle of common-place city blocks, lying

between and to east and west of Lenox and Seventh Avenues, stretching nearly a mile north

and south—and unaccountably full of Negroes.

Another Harlem is savored by the few—a Harlem of racy music and racier dancing, of

cabarets famous or notorious according to their kind, of amusement in which abandon and

sophistication are cheek by jowl—a Harlem which draws the connoisseur in diversion as

well as the undiscriminating sightseer. This Harlem is the fertile source of the

"shuffling " and "rollin’" and "runnin’ wild" revues that

establish themselves season after season in "downtown" theaters. It is part of

the exotic fringe of the metropolis.

Beneath this lies again the Harlem of the newspapers—a Harlem of monster parades and

political flummery, a Harlem swept by revolutionary oratory or draped about the mysterious

figures of Negro "millionaires," a Harlem pre-occupied with naive adjustments to

a white world—a Harlem, in short, grotesque with the distortions of journalism.

YET in final analysis, Harlem is neither slum, ghetto, resort or colony, though it is in

part all of them. It is—or promises at least to be—a race capital. Europe seething in a

dozen centers with emergent nationalities, Palestine full of a renascent Judaism—these

are no more alive with the spirit of a racial awakening than Harlem; culturally and

spiritually it focuses a people. Negro life is not only founding new centers, but finding

a new soul. The tide of Negro migration, northward and city-ward, is not to be fully

explained as a blind flood started by the demands of war industry coupled with the

shutting off of foreign migration, or by the pressure of poor crops coupled with increased

social terrorism in certain sections of the South and Southwest. Neither labor demand, the

boll-weevil nor the Ku Klux Klan is a basic factor, however contributory any or all of

them may have been. The wash and rush of this human tide on the beach line of the northern

city centers is to be explained primarily in terms of a new vision of opportunity, of

social and economic freedom of a spirit to seize, even in the face of an extortionate and

heavy toll, a chance for the improvement of conditions. With each successive wave of it,

the movement of the Negro migrant becomes more and more like that of the European waves at

their crests, a mass movement toward the larger and the more democratic chance—in the

Negro’s case a deliberate flight not only from countryside to city, but from medieaval

America to modern.

The secret lies close to what distinguishes Harlem from the ghettos with which it is

sometimes compared. The ghetto picture is that of a slowly dissolving mass, bound by ties

of custom and culture and association, in the midst of a freer and more varied society.

From the racial standpoint, our Harlems are themselves crucibles. Here in Manhattan is not

merely the largest Negro community in the world, but the first concentration in history of

so many diverse elements of Negro life. It has attracted the African, the West Indian, the

Negro American; has brought together the Negro of the North and the Negro of the South;

the man from the city and the man from the town and village; the peasant, the student, the

business man, the professional man, artist, poet, musician, adventurer and worker,

preacher and criminal, exploiter and social outcast. Each group has come with its own

separate motives and for its own special ends, but their greatest experience has been the

finding of one another. Proscription and prejudice have thrown these dissimilar elements

into a common area of contact and interaction. Within this area, race sympathy and unity

have determined a further fusing of sentiment and experience. So what began in terms of

segregation becomes more anymore, as its elements mix and react, the laboratory of a great

race-welding. Hitherto, it must be admitted that American Negroes have been a race more in

name than in fact, or to be exact, more in sentiment than in experience. The chief bond

between them has been that of a common condition rather than a common consciousness; a

problem in common rather than a life in common. In Harlem, Negro life is seizing upon its

first chances for group expression and self-determination. That is why our comparison is

taken with those nascent centers of folk-expression and self-determination which are

playing a creative part in the world today. Without pretense to their political

significance, Harlem has the same role to play for the New Negro as Dublin has had for the

New Ireland or Prague for the New Czechoslovakia.

It is true the formidable centers of our race life, educational, industrial, financial,

are not in Harlem, yet here, nevertheless, are the forces that make a group known and felt

in the world. The reformers, the fighting advocates, the inner spokesmen, the poets,

artists and social prophets are here, and pouring in toward them are the fluid ambitious

youth and pressing in upon them the migrant masses. The professional observers, and the

enveloping communities as well, are conscious of the physics of this stir and movement, of

the cruder and more obvious facts of a ferment and a migration. But they are as yet

largely unaware of the psychology of it, of the galvanising shocks and reactions, which

mark the social awakening and internal reorganization which are making a race out of its

own disunited elements.

A railroad ticket and a suitcase, like a Bagdad carpet, transport the Negro peasant from

the cotton-field and farm to the heart of the most complex urban civilization. Here in the

mass, he must and does survive a jump of two generations in social economy and of a

century and more in civilisation. Meanwhile the Negro poet, student, artist, thinker, by

the very move that normally would take him off at a tangent from the masses, finds himself

in their midst, in a situation concentrating the racial side of his experience and

heightening his race-consciousness. These moving, half-awakened newcomers provide an

exceptional seed-bed for the germinating contacts of the enlightened minority. And that is

why statistics are out of joint with fact in Harlem, and will be for a generation or so.

HARLEM, I grant you, isn’t typical—but it is significant, it is prophetic. No sane

observer, however sympathetic to the new trend, would contend that the great masses are

articulate as yet, but they stir, they move, they are more than physically restless. The

challenge of the new intellectuals among them is clear enough—the "race

radicals" and realists who have broken with the old epoch of philanthropic guidance,

sentimental appeal and protest. But are we after all only reading into the stirrings

Video Preview

Read Konecky & Konecky’s description of Voices of the Harlem Renaissance: Originally Published as The New Negro an Interpretation.

Copyright © 2020 Konecky & Konecky/Alain Locke and Introduction by Troy Johnson. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher or author.