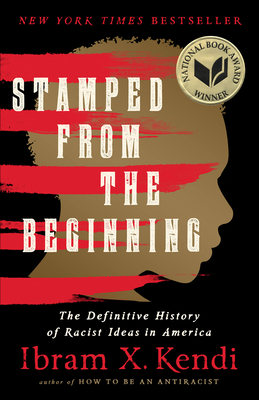

Book Excerpt – Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America

Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America

by Ibram X. Kendi

Publication Date: Jun 20, 2023

List Price: $22.99

Format: Paperback, 640 pages

Classification: Nonfiction

ISBN13: 9781645030393

Imprint: Bold Type Books

Publisher: Hachette Book Group

Parent Company: Lagardère Group

Read a Description of Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America

Copyright © 2023 Hachette Book Group/Ibram X. Kendi No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher or author. The format of this excerpt has been modified for presentation here.

PART I

Cotton Mather

CHAPTER 1

Human Hierarchy

THEY WEATHERED BRUTAL WINTERS, suffered diseases, and learned to cope with the resisting Native Americans. But nothing brought more destruction to Puritan settlements than the Great Hurricane of 1635. On August 16, 1635, the hurricane—today judged to be perhaps Category 3—thundered up the Atlantic Coast, brushing Jamestown and passing over eastern Long Island. The storm’s eye glanced at Providence to the east and moved inland, snatching up thousands of trees like weeds. In the seven-year-old Massachusetts Bay Colony, the hurricane smashed down English homes as if they were ants, before reaching the Atlantic Ocean and swinging knockout waves onto the New England shores.

Large ships from England transporting settlers and supplies were sitting ducks. Seamen anchored one ship, the James, off the coast of New Hampshire to wait out the hurricane. Suddenly, a powerful wave sliced the ship’s anchors and cables like an invisible knife. Seamen slashed the third cable in distress and hoisted sail to cruise back out to a safer sea. The winds smashed the new sail into “rotten rags,” recorded notable Puritan minister Richard Mather in his diary. As the rags disappeared into the ocean, so did hope.

Abducted now by the hurricane, the ship headed toward a mighty rock. All seemed lost. Richard Mather and fellow passengers cried out to the Lord for deliverance. Using “his own immediate good hand,” God guided the ship around the mighty rock, Mather later testified. The sea calmed. The crew hurriedly rigged the ship with new sails. The Lord blew “a fresh gale of wind,” allowing the captain to navigate away from danger. The battered James arrived in Boston on August 17, 1635. All one hundred passengers credited God for their survival. Richard Mather took the deliverance as a charge “to walk uprightly before him as long as we live.”1

As a Puritan minister, Richard Mather had walked uprightly through fifteen years of British persecution before embarking on the perilous journey across the Atlantic to begin life anew in New England. There, he would be reunited with his illustrious ministerial friend John Cotton, who had faced British persecution for twenty years in Boston, England. In 1630, Cotton had given the farewell sermon to hundreds of Puritan founders of New England communities, blessing their fulfillment of God’s prophetic vision. As dissenters from the Church of England, Puritans believed themselves to be God’s chosen piece of humanity, a special, superior people, and New England, their Israel, was to be their exceptional land.2

Within a week of the Great Hurricane, Richard Mather was installed as pastor of Dorchester’s North Church near the renowned North Church of the new Boston, which was pastored by John Cotton. Mather and Cotton then embarked on a sacred mission to create, articulate, and defend the New England Way. They used their pens as much as their pulpits, and they used their power as much as their pens and pulpits. They penned the colonies’ first adult and children’s books as part of this endeavor. Mather, in all likelihood, steered the selection of Henry Dunster to lead colonial America’s first college, Harvard’s forerunner, in 1640. And Cotton did not mind when Dunster fashioned Harvard’s curriculum after their alma mater, Cambridge, setting off an ideological trend. Like the founders of Cambridge and Harvard before them, the founders of William & Mary (1693), Yale (1701), the University of Pennsylvania (1740), Princeton (1746), Columbia (1754), Brown (1764), Rutgers (1766), and Dartmouth (1769)—the other eight colonial colleges—regarded ancient Greek and Latin literature as universal truths worthy of memorization and unworthy of critique. At the center of the Old and New England Greek library hailed the resurrected Aristotle, who had come under suspicion as a threat to doctrine among some factions in Christianity during the medieval period.3

In studying Aristotle’s philosophy, Puritans learned rationales for human hierarchy, and they began to believe that some groups were superior to other groups. In Aristotle’s case, ancient Greeks were superior to all non-Greeks. But Puritans believed they were superior to Native Americans, the African people, and even Anglicans—that is, all non-Puritans. Aristotle, who lived from 384 to 322 BCE, concocted a climate theory to justify Greek superiority, saying that extreme hot or cold climates produced intellectually, physically, and morally inferior people who were ugly and lacked the capacity for freedom and self-government. Aristotle labeled Africans “burnt faces”—the original meaning in Greek of “Ethiopian”—and viewed the “ugly” extremes of pale or dark skins as the effect of the extreme cold or hot climates. All of this was in the interest of normalizing Greek slaveholding practices and Greece’s rule over the western Mediterranean. Aristotle situated the Greeks, in their supreme, intermediate climate, as the most beautifully endowed superior rulers and enslavers of the world. “Humanity is divided into two: the masters and the slaves; or, if one prefers it, the Greeks and the Barbarians, those who have the right to command; and those who are born to obey,” Aristotle said. For him, the enslaved peoples were “by nature incapable of reasoning and live a life of pure sensation, like certain tribes on the borders of the civilized world, or like people who are diseased through the onset of illnesses like epilepsy or madness.”4

By the birth of Christ or the start of the Common Era, Romans were justifying their slaveholding practices using Aristotle’s climate theory, and soon the new Christianity began to contribute to these arguments. For early Christian theologians—whom Puritans studied alongside Aristotle—God ordained the human hierarchy. St. Paul introduced, in the first century, a three-tiered hierarchy of slave relations—heavenly master (top), earthly master (middle), enslaved (bottom). “He who was free when called is a slave of Christ,” he testified in 1 Corinthians. “Slaves” were to “obey in everything those that are your earthly masters, not with eyeservice as men-pleasers, but in singleness of heart, fearing the Lord.” In a crucial caveat in Galatians 3:28, St. Paul equalized the souls of masters and slaves as “all one in Christ Jesus.”

All in all, ethnic and religious and color prejudice existed in the ancient world. Constructions of races—White Europe, Black Africa, for instance—did not, and therefore racist ideas did not. But crucially, the foundations of race and racist ideas were laid. And so were the foundations for egalitarianism, antiracism, and antislavery laid in Greco-Roman antiquity. “The deity gave liberty to all men, and nature created no one a slave,” wrote Alkidamas, Aristotle’s rival in Athens. When Herodotus, the foremost historian of ancient Greece, traveled up the Nile River, he found the Nubians “the most handsome of peoples.” Lactantius, an adviser to Constantine I, the first Christian Roman emperor, announced early in the fourth century: “God who creates and inspires men wished them all to be fair, that is, equal.” St. Augustine, an African church father in the fourth and fifth centuries, maintained that “whoever is born anywhere as a human being, that is, as a rational mortal creature, however strange he may appear to our senses in bodily form or colour or motion or utterance, or in any faculty, part or quality of his nature whatsoever, let no true believer have any doubt that such an individual is descended from the one man who was first created.” However, these antislavery and egalitarian champions did not accompany Aristotle and St. Paul into the modern era, into the new Harvard curriculum, or into the New England mind seeking to justify slavery and the racial hierarchy it produced.5

When John Cotton drafted New England’s first constitution in 1636, Moses his judicials, he legalized the enslavement of captives taken in just wars as well as “such strangers as willingly selle themselves or are sold to us.” The New England way imitated the Old England way on slavery. Cotton reproduced the policies of his British peers close and far away. In 1636, Barbados officials announced that “Negroes and Indians that come here to be sold, should serve for Life, unless a Contract was before made to the contrary.”6

The Pequot War, the first major war between the New England colonists and the area’s indigenous peoples, erupted in 1637. Captain William Pierce forced some indigenous war captives onto the Desire, the first slaver to leave British North America. The ship sailed to the Isla de Providencia off Nicaragua, where “Negroes” were reportedly “being . . . kept as perpetuall servants.” Massachusetts governor John Winthrop recorded Captain Pierce’s historic arrival back into Boston in 1638, noting that his ship was hauling “salt, cotton, tobacco and Negroes.”7

The first generation of Puritans began rationalizing the enslavement of these “Negroes” without skipping a Christian beat. Their chilling nightmares of persecution were not the only hallucinations the Puritans had carried over the Atlantic waters in their minds to America. From the first ships that landed in Virginia in 1607, to the ships that survived the Great Hurricane of 1635, to the first slave ships, some British settlers of colonial America carried across the sea Puritan, biblical, scientific, and Aristotelian rationalizations of slavery and human hierarchy. From Western Europe and the new settlements in Latin America, some Puritans carried across their judgment of the many African peoples as one inferior people. They carried across racist ideas—racist ideas that preceded American slavery, because the need to justify African slavery preceded colonial America.

AFTER ARAB MUSLIMS conquered parts of North Africa, Portugal, and Spain during the seventh century, Christians and Muslims battled for centuries over the prize of Mediterranean supremacy. Meanwhile, below the Sahara Desert, the West African empires of Ghana (700–1200), Mali (1200–1500), and Songhay (1350–1600) were situated at the crossroads of the lucrative trade routes for gold and salt. A robust trans-Saharan trade emerged, allowing Europeans to obtain West African goods through Muslim intermediaries.

Ghana, Mali, and Songhay developed empires that could rival in size, power, scholarship, and wealth any in the world. Intellectuals at universities in Timbuktu and Jenne pumped out scholarship and pumped in students from around West Africa. Songhay grew to be the largest. Mali may have been the most illustrious. The world’s greatest globe-trotter of the fourteenth century, who trotted from North Africa to Eastern Europe to Eastern Asia, decided to see Mali for himself in 1352. “There is complete security in their country,” Moroccan Ibn Battuta marveled in his travel notes. “Neither traveler nor inhabitant in it has anything to fear from robbers or men of violence.”8

Ibn Battuta was an oddity—an abhorred oddity—among the Islamic intelligentsia in Fez, Morocco. Hardly any scholars had traveled far from home, and Battuta’s travel accounts threatened their own armchair credibility in depicting foreigners. None of Battuta’s antagonists was more influential than the intellectual tower of the Muslim world at that time, Tunisian Ibn Khaldun, who arrived in Fez just as Battuta returned from Mali. “People in the dynasty (in official positions) whispered to each other that he must be a liar,” Khaldun revealed in 1377 in The Muqaddimah, the foremost Islamic history of the premodern world. Khaldun then painted a very different picture of sub-Sahara Africa in The Muqaddimah: “The Negro nations are, as a rule, submissive to slavery,” Khaldun surmised, “because (Negroes) have little that is (essentially) human and possess attributes that are quite similar to those of dumb animals.” And the “same applies to the Slavs,” argued this disciple of Aristotle. Following Greek and Roman justifiers, Khaldun used climate theory to justify Islamic enslavement of sub-Saharan Africans and Eastern European Slavs—groups sharing only one obvious characteristic: their remoteness. “All their conditions are remote from those of human beings and close to those of wild animals,” Khaldun suggested. Their inferior conditions were neither permanent nor hereditary, however. “Negroes” who migrated to the cooler north were “found to produce descendants whose colour gradually turns white,” Khaldun stressed. Dark-skinned people had the capacity for physical assimilation in a colder climate. Later, cultural assimilationists would imagine that culturally inferior African people, placed in the proper European cultural environment, could or should adopt European culture. But first physical assimilationists like Khaldun imagined that physically inferior African people, placed in the proper cold environment, could or should adopt European physicality: white skin and straight hair.9

Ibn Khaldun did not intend merely to demean African people as inferior. He intended to belittle all the different-looking African and Slavic peoples whom the Muslims were trading as slaves. Even so, he reinforced the conceptual foundation for racist ideas. On the eve of the fifteenth century, Khaldun helped bolster the foundation for assimilationist ideas, for racist notions of the environment producing African inferiority. All an enslaver had to do was to stop justifying Slavic slavery and inferiority using climate theory, and focus the theory on African people, for the racist attitude toward dark-skinned people to be complete.

There was one enslavement theory focused on Black people already circulating, a theory somehow derived from Genesis 9:18–29, which said “that Negroes were the children of Ham, the son of Noah, and that they were singled out to be black as the result of Noah’s curse, which produced Ham’s colour and the slavery God inflicted upon his descendants,” as Khaldun explained. The lineage of this curse of Ham theory curves back through the great Persian scholar Tabari (838–923) all the way to Islamic and Hebrew sources. God had permanently cursed ugly Blackness and slavery into the very nature of African people, curse theorists maintained. As strictly a climate theorist, Khaldun discarded the “silly story” of the curse of Ham.10

Although it clearly supposed Black inferiority, the curse theory was like an unelected politician during the medieval period. Muslim and Christian enslavers hardly gave credence to the curse theory: they enslaved too many non-Black descendants of Shem and Japheth, Ham’s supposed non-cursed brothers, for that. But the medieval curse theorists laid the foundation for segregationist ideas and for racist notions of Black genetic inferiority. The shift to solely enslaving Black people, and justifying it using the curse of Ham, was in the offing. Once that shift occurred, the disempowered curse theory became empowered, and racist ideas truly came into being.11

CHAPTER 2

Origins of Racist Ideas

RICHARD MATHER AND John Cotton inherited from the English thinkers of their generation the old racist ideas that African slavery was natural and normal and holy. These racist ideas were nearly two centuries old when Puritans used them in the 1630s to legalize and codify New England slavery—and Virginians had done the same in the 1620s. Back in 1415, Prince Henry and his brothers had convinced their father, King John of Portugal, to capture the principal Muslim trading depot in the western Mediterranean: Ceuta, on the northeastern tip of Morocco. These brothers were envious of Muslim riches, and they sought to eliminate the Islamic middleman so that they could find the southern source of gold and Black captives.

After the battle, Moorish prisoners left Prince Henry spellbound as they detailed trans-Saharan trade routes down into the disintegrating Mali Empire. Since Muslims still controlled these desert routes, Prince Henry decided to “seek the lands by the way of the sea.” He sought out those African lands until his death in 1460, using his position as the Grand Master of Portugal’s wealthy Military Order of Christ (successor of the Knights Templar) to draw venture capital and loyal men for his African expeditions.

In 1452, Prince Henry’s nephew, King Afonso V, commissioned Gomes Eanes de Zurara to write a biography of the life and slave-trading work of his “beloved uncle.” Zurara was a learned and obedient commander in Prince Henry’s Military Order of Christ. In recording and celebrating Prince Henry’s life, Zurara was also implicitly obscuring his Grand Master’s monetary decision to exclusively trade in African slaves. In 1453, Zurara finished the inaugural defense of African slave-trading, the first European book on Africans in the modern era. The Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea begins the recorded history of anti-Black racist ideas. Zurara’s inaugural racist ideas, in other words, were a product of, not a producer of, Prince Henry’s racist policies concerning African slave-trading.1

The Portuguese made history as the first Europeans to sail along the Atlantic beyond the Western Sahara’s Cape Bojador in order to bring enslaved Africans back to Europe, as Zurara shared in his book. The six caravels, carrying 240 captives, arrived in Lagos, Portugal, on August 6, 1444. Prince Henry made the slave auction into a spectacle to show the Portuguese had joined the European league of serious slave-traders of African people. For some time, the Genoese of Italy, the Catalans of northern Spain, and the Valencians of eastern Spain had been raiding the Canary Islands or purchasing African slaves from Moroccan traders. Zurara distinguished the Portuguese by framing their African slave-trading ventures as missionary expeditions. Prince Henry’s competitors could not play that mind game as effectively as he did, in all likelihood because they still traded so many Eastern Europeans.2

But the market was changing. Around the time the Portuguese opened their sea route to a new slave export area, the old slave export area started to close up. In Ibn Khaldun’s day, most of the captives sold in Western Europe were Eastern Europeans who had been seized by Turkish raiders from areas around the Black Sea. So many of the seized captives were “Slavs” that the ethnic term became the root word for “slave” in most Western European languages. By the mid-1400s, Slavic communities had built forts against slave raiders, causing the supply of Slavs in Western Europe’s slave market to plunge at around the same time that the supply of Africans was increasing. As a result, Western Europeans began to see the natural Slav(e) not as White, but Black.3

THE CAPTIVES IN 1444 disembarked from the ship and marched to an open space outside of the city, according to Zurara’s chronicle. Prince Henry oversaw the slave auction, mounted on horseback, beaming in delight. Some of the captives were “white enough, fair to look upon, and well proportioned,” while others were “like mulattoes,” Zurara reported. Still others were “as black as Ethiops, and so ugly” that they almost appeared as visitors from Hell. The captives included people in the many shades of the Tuareg Moors as well as the dark-skinned people whom the Tuareg Moors may have enslaved. Despite their different ethnicities and skin colors, Zurara viewed them as one people—one inferior people.4

Zurara made it a point to remind his readers that Prince Henry’s “chief riches” in quickly seizing forty-six of the most valuable captives “lay in his own purpose; for he reflected with great pleasure upon the salvation of those souls that before were lost.” In building up Prince Henry’s evangelical justification for enslaving Africans, Zurara reduced these captives to barbarians who desperately needed not only religious but also civil salvation. “They lived like beasts, without any custom of reasonable beings,” he wrote. What’s more, “they have no knowledge of bread or wine, and they were without covering of clothes, or the lodgement of houses; and worse than all, they had no understanding of good, but only knew how to live in bestial sloth.” In Portugal, their lot was “quite the contrary of what it had been.” Zurara imagined slavery in Portugal as an improvement over their free state in Africa.5

Zurara’s narrative covered from 1434 to 1447. During that period, Zurara estimated, 927 enslaved Africans were brought to Portugal, “the greater part of whom were turned into the true path of salvation.” Zurara failed to mention that Prince Henry received the royal fifth (quinto), or about 185 of those captives, for his immense fortune. But that was irrelevant to his mission, a mission he accomplished. For convincing readers, successive popes, and the reading European world that Prince Henry’s Portugal did not engage in the slave trade for money, Zurara was handsomely rewarded as Portugal’s chief royal chronicler, and he was given two more lucrative commanderships in the Military Order of Christ. Zurara’s bosses quickly reaped returns from their slave trading. In 1466, a Czech traveler noticed that the king of Portugal was making more selling captives to foreigners “than from all the taxes levied on the entire kingdom.”6

Zurara circulated the manuscript of The Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea to the royal court as well as to scholars, investors, and captains, who then read and circulated it throughout Portugal and Spain. Zurara died in Lisbon in 1474, but his ideas about slavery endured as the slave trade expanded. By the 1490s, Portuguese explorers had crept southward along the West African coast, rounding the Cape of Good Hope into the Indian Ocean. In their growing networks of ports, agents, ships, crews, and financiers, pioneering Portuguese slave-traders and explorers circulated the racist ideas in Zurara’s book faster and farther than the text itself had reached. The Portuguese became the primary source of knowledge on unknown Africa and the African people for the original slave-traders and enslavers in Spain, Holland, France, and England. By the time German printer Valentim Fernandes published an abridged version of Zurara’s book in Lisbon in 1506, enslaved Africans—and racist ideas—had arrived in the Americas.7

IN 1481, THE PORTUGUESE began building a large fort, São Jorge da Mina, known simply as Elmina, or “the mine,” as part of their plan to acquire Ghanaian gold. In due time, this European building, the first known to be erected south of the Sahara, became West Africa’s largest slave-trading post, the nucleus of Portugal’s operations in West Africa. A Genoese explorer barely three decades old may have witnessed the erection of Elmina Castle. Christopher Columbus, newly married to the daughter of a Genoese protégé of Prince Henry, desired to make his own story—but not in Africa. He looked instead to East Asia, the source of spices. After Portuguese royalty refused to sponsor his daring westward expedition, Queen Isabel of Spain, a great-niece of Prince Henry, consented. So in 1492, after sixty-nine days at sea, Columbus’s three small ships touched the shores that Europeans did not know existed: first the glistening Bahamas, and the next night, Cuba.8

Almost from Columbus’s arrival, Spanish colonists began to degrade and enslave the indigenous American peoples, naming them negros da terra (Blacks from the land), transferring their racist constructions of African people onto Native Americans. Over the years that followed, they used the force of the gun and the Bible in one of the most frightful and sudden massacres in human history. Thousands of Native Americans died resisting enslavement. More died from European diseases, from the conditions they suffered while forcibly tilling fields, and on death marches searching and mining for gold. Thousands of Native Americans were driven off their land by Spanish settlers dashing into the colonies after riches. Spanish merchant Pedro de Las Casas settled in Hispaniola in 1502, the year the first enslaved Africans disembarked from a Portuguese slave ship. He brought along his eighteen-year-old son Bartolomé, who would play an outsized role in the direction slavery took in the so-called New World.9

By 1510, Bartolomé de Las Casas had accumulated land and captives as well as his ordination papers as the Americas’ first priest. He felt proud in welcoming the Dominican Friars to Hispaniola in 1511. Sickened by Taíno slavery, the Friars stunned Las Casas and broke abolitionist ground, rejecting the Spanish line (taken from the Portuguese) that the Taíno people benefited, through Christianity, from slavery. King Ferdinand promptly recalled the Dominican Friars, but their antislavery sermons never left Bartolomé de Las Casas. In 1515, he departed for Spain, where he would conduct a lifelong campaign to ease the suffering of Native Americans, and, possibly more importantly—solve the settlers’ extreme labor shortage. In one of his first written pleas in 1516, Las Casas suggested importing enslaved Africans to replace the rapidly declining Native American laborers, a plea he made again two years later. Alonso de Zuazo, a University of Salamanca–trained lawyer, had made a similar recommendation back in 1510. “General license should be given to bring negroes, a [people] strong for work, the opposite of the natives, so weak who can work only in undemanding tasks,” Zuazo wrote. In time, some indigenous peoples had caught wind of this new racist idea, and they readily agreed that a policy of importing African laborers would be better. An indigenous group in Mexico complained that the “difficult and arduous work” involved in harnessing a sugar crop was “only for the blacks and not for the thin and weak Indians.” Las Casas and company birthed twins—racist twins that some Native Americans and Africans took in: the myth of the physically strong, beastly African, and the myth of the physically weak Native American who easily died from the strain of hard labor.10