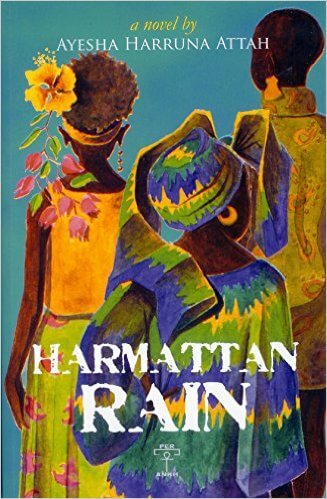

Book Excerpt – Harmattan Rain

Harmattan Rain

by Ayesha Harruna Attah

Fiction, Paperback

More Info ▶

Ernest sat in the driver’s seat of the Pontiac tapping his fingers on the steering wheel. Lizzie packed Akua Afriyie, Naa Tsoo, Kwame and Ernest Jr. onto the back seat. She looked back at Abokyi who was grinning, holding on to the open gate. She sighed. It was a sigh filled with nostalgia. It was a sigh swathed in fear so strong, she was ready to cancel this whole trip.

“Aren’t you ready?” Ernest asked her.

“I am,” Lizzie said as she opened the passenger seat door, surprised at his testiness. She sat down, rested Tsotsoo in her lap. All their suitcases were packed in the trunk. Tsotsoo’s baby food was safely stored in the snakeskin bag at her feet. She’d taken enough clothes for the children. “Ernie,” she said, “at the gate, let me have a word with Abokyi.”

“Make it snappy.”

“All right.” And what is wrong with this one? she wondered. Abokyi stuck his head through the window. “Abokyi,” she said, drawing her own head back. “We’ll be away for two weeks. As usual, don’t let anyone in. And don’t tell them we’ve traveled. Just tell them we’ve gone to work.”

“Is this necessary?” Ernest asked. Lizzie eyed him.

“Yes,” she said.

“Abokyi, if my mother comes by you can let her in.”

“Yes, massa!”

Lizzie eyed him again. “OK, that’s it. Senam will give you your food. Make sure to water the plants! Bye!”

“Safe trip!” Abokyi said, smiling.

“Bye, Abokyi,” the children chorused from the backseat.

“And what’s ailing you?” Lizzie asked.

“Have you looked at the time? We’re going to get stuck in that Nsawam Road traffic. And we still have to pass by Asantewa’s. Do we have to?”

“Yes, I have to give her the keys.” She sucked her teeth and looked out the window. She was nervous enough as it was, and now Ernest was acting strangely.

They drove through Mallam Attah’s gated entrance. The market bustled with women slinging baskets around their arms, market women haggling and calling for customers. Ernest slowed down. In front of them walked a woman in a blue and green cloth, her head wrap held high, her buttocks swaying to the beat of the morning.

“This one. Stop!” Lizzie pointed at an oily blue storefront.

“Give me the keys,” Ernest said.

“I was going to …” Lizzie actually liked this side of Ernest. She’d never seen him take control of any situation like he was doing now. He strode into Asantewa’s store. In his peach-colored shirt, slightly flared burgundy trousers, he exuded a somewhat cocky air. His hair was overgrown with its parting on the right. Straining her neck to look into Asantewa’s store, she noticed a lot of the shelves were empty. Boxes sat on the floor. Lizzie waved at Asantewa from the car.

Asantewa walked over with Ernest. “Thanks,” she said.

“I put the money for Senam and Abokyi under your door.”

“OK,” Asantewa said.

Ernest was back in the car.

“Let’s see, what else?” Lizzie said, trying hard not to notice Ernest glaring at her. She was sure he was seething now. A part of her was trying to delay this trip as much as possible. “You might have to keep an eye out for Abokyi and those plants. Either he doesn’t water them or he floods them with water. Any messages for Papa Yaw or Mama Efua?”

“Give them my love. Safe journey!”

“See you in two weeks!” Lizzie said.

Ernest muttered something under his breath. “Ready?” he asked loudly.

“Yes.”

He drove to an Agip filling station close to the market. All four of the transparent petrol dispensers were empty. A bored attendant sitting under the awning of the station’s mart lazily waved at them.

“No petrol!” he shouted.

Ernest sucked his teeth. They drove to two other filling stations and heard the same story. The only place with petrol was at the Kwame Nkrumah Circle, an attendant told them at the last place.

Lizzie saw a line of cars snake out of the station. It wasn’t even a line. It was chaos as taxi drivers tried to cut in. Lizzie felt ashamed. But only fleetingly. Every minute they spent in the queue delayed the moment of arrival in Adukrom No. 2.

“This is exactly what I was trying to avoid,” Ernest said.

“Sorry,” Lizzie said. She turned round. She made sure the children were well dressed especially for today—Akua Afriyie and Naa Tsoo in their matching yellow A-line dresses and the boys in their button-down white shirts and tan trousers. “You all look lovely,” she said to them.

“Thank you,” they chorused.

“I still don’t understand, Mamaa,” Akua Afriyie said, “why I had to wear the same dress as Naa Tsoo.”

“Because she likes you and wants to be just like you,” Lizzie said.

“But she’s eight and I’m ten. We can’t wear the same things.”

“Akua, it’s too late to complain now.” Lizzie looked forward, avoiding Ernest’s eyes. She could feel the hostility emanating from him, like the heat in the air on a harmattan afternoon. The car ahead of them inched forward. Ernest closed the gap. Tsotsoo gurgled. Lizzie rocked her. She felt the muggy heat rising the longer they stayed in the queue. “Maybe there’ll be petrol along the way,” she said.

“I’m not taking any chances,” Ernest snapped at her.

By the time they’d filled up it was a quarter past ten.

“All right, gang,” Ernest said, “to Adukrom No. 2 we go!”

Lizzie looked at him. She was amazed at how fast his mood switched. Maybe it was her fault, taking him away from Gertrude.

He drove along Nsawam Road, parts of which had been washed away by the recent flooding in Accra. The Pontiac bumped in and out of a huge crack in the earth. Tsotsoo wailed.

“Shhh!” Lizzie said, rocking her in her arms. She tried to imagine what Adukrom No. 2 had become. She was sure it looked the same. Papa Yaw’s house must not have changed. She hoped they hadn’t cut down the khaya tree. The air rushing in was blowing the curls on her head into her face. As she rolled up the window, she was fascinated at the number of new houses being built along the Nsawam Road.

As if he’d read her thoughts Ernest said, “In a few years, this area will be considered Accra.”

They drove for an hour. Fear gripped Lizzie’s tongue.

“You’re quiet today,” Ernest said.

“I’m nervous. Wouldn’t you be?”

“It’ll be fine.”

“And why are you being nice to me now? At nine this morning you were behaving like a certain German person I shall not name.”

“I just wanted us to leave on time.”

“German temperament coming in, huh?” Lizzie said, looking at the roadside, a continuous sea of green.

The farther they drove from Accra, the higher the grass grew. The more the road undulated, the taller the trees became. A thick cloud Lizzie hadn’t seen coming burst open, sending down a flash of rain, wetting the tarmac, washing their car and leaving droplets on all the windows.

“Wow,” Akua Afriyie said. “It only rained on that side!”

“Mummy, I want to weewee,” Naa Tsoo said.

“Me too,” Kwame said.

“Me too,” Ernest Jr. repeated.

Lizzie looked at Ernest. “Can we stop?” she asked.

“We’re almost at the Nkawkaw Rest Stop,” Ernest said.

“Everybody count to ten and hold your weewee. Let’s go, one, two …”

The children counted with Lizzie. The loudest voice was Ernest Jr.’s and he didn’t even know how to count. His two-year-old babble floated above the other children’s voices. “Waa, waa, ten!”

At Nkawkaw, a little town buzzing with trotros, private sedans and taxis coming and going, passengers milling about, hawkers screaming their wares, Ernest pulled up behind a white mammy lorry.

Lizzie took the girls, Ernest, the boys. A narrow gutter ran through the women’s urinal. The shallow depression reeked of urine. Two women squatted, the rush of their released waters flowing through the gutter.

“Don’t wet your panties,” Lizzie said to Akua Afriyie and Naa Tsoo. She watched Akua Afriyie spread her legs over the gutter, pull her panties down, raise her A-line dress, show her pudendum to the whole world, and then sit on her haunches. Her urine splashed into the gutter, spraying her white sandals.

Lizzie shook her head. Naa Tsoo looked ready to copy her older sister. Lizzie wondered when the mimicry would end. Akua Afriyie, in her opinion, was hardly a suitable role model. She passed Tsotsoo to Akua Afriyie. “Don’t drop her, Akua,” Lizzie warned. She squatted, hiked up her pink boubou and unleashed a torrent of liquid she herself had been holding in. She took Tsotsoo from Akua Afriyie’s arms, studied her girls to make sure they were still presentable. Why they don’t build these places with sinks, I don’t understand, she thought. “Let’s go get Papa and the boys,” she said.

The boys were already at the car.

“Maybe we should eat now,” she said.

“Now?” Ernest asked.

“I don’t want us to stop again after here,” Lizzie said. Her current state of mind reminded her of her nursing school days. After exams she was always gripped with the worst feeling that she’d failed. She wanted nothing to do with the results. Soon after, rising above the fear, she felt a surge of excitement, a sadistic yearning to see what her results were, no matter how good or bad they were. Now her sadistic yearning for Adukrom No. 2 was surfacing. She wanted to show off her new family. Show off who she’d become. If they accepted her, fine. If they didn’t, fine.

Ernest popped open the trunk.

Lizzie strode over to his side and took out a bottle of water and the basket Senam had prepared with tuna sandwiches.

With Ernest leading the way, the family walked toward the main rest stop building. Lizzie handed him the basket.

“Everyone over here! Time to wash your hands.” She gathered the children around and poured the water in the bottle over their fingers.

They walked into a concrete open space swarming with travelers, drivers and young women hawking oranges and bottled drinks. Ernest stood by a grey bench and table. The children slid along the bench.

“Sssss,” Ernest called out to a girl balancing a silver tray of oranges on her head as she peeled an orange in a spiral. “Six oranges, please.”

“One new cedi,” the girl said, slicing the tops off the oranges.

“Thank you,” Ernest said, handing her a rumpled note.

Lizzie picked out paper plates from the basket and placed one in front of each child. She distributed the sandwiches on the plates.

She caught Ernest Jr. stuffing his mouth with his sandwich. “Junior! A bite at a time,” she said.

“Wame did some,” Ernest Jr. said.

“Kwame, don’t stuff your mouth!” She looked around the enclosure. Two men were smoking. They kept studying their cigarettes before lifting them to their lips.

“… these made in Ghana cigarettes are really no good,” one of them said.

“I know, man. What is Busia going to ban next? Fresh air?” They burst into peals of laughter. She looked at Ernest.

“It’s true,” he said. “The government is not letting us bring anything in. Not even pens! If I’d gone to Germany, I could have found a way.”

“Sorry,” Lizzie said. She felt bad, but not entirely. Germany was now a sore spot. Germany was Gertrude. Lizzie bundled the children back into the car.

As they drove on, her stomach knotted over. She couldn’t remember the turning to Adukrom No. 2, especially coming from this direction. In her Suaadie Girls days, she’d come from the north down. Now they were coming up from the south. There was a cedar tree close to the entrance with one colossal branch pointing down. That was her landmark. She stared intently at all the approaching trees.

It was in the search for the one-armed cedar that she saw the accident.

“Close your eyes, children,” she said.

A huge timber truck had indented half of a white mammy lorry and blocked off half of the road. Ernest drove slowly by the accident. People were pulling out wounded persons from the windows of the lorry. Lizzie could feel her insides scraping, as if she was the one being rescued. She looked back at her children. They were gawking out the window.

“Didn’t I tell you to close your eyes?” she shouted. “Close your eyes! Ernie, drive carefully,” she said. She looked back through the rearview mirror. “That was horrible.”

They drove in silence, Lizzie’s insides still itching. Fear rose in her again. Now she wanted to delay their arrival. She thought about everything Adukrom No. 2 stood for: Bador Samed. Papa Yaw. Her past. How was this all going to go down? she wondered.

Looming in the distance, to the left of the road was the one-armed cedar. It stood grey, its bark gnarled, its crown completely leafless.

“Turn right,” Lizzie said. The road to Adukrom No. 2 was now tarred. Most of the trees that had covered the entrance had disappeared.

The village looked small, sparser than she remembered it. Corrugated tin roofs had replaced the thatch on most of the homes. A few new houses were in places she didn’t remember and were built of cement. “You can park by that tree,” she said, pointing to a neem tree. Emotion rose up in her, swelled in her chest. She didn’t want to cry. She opened the door for the children to pour out. They ran forward as if they knew the place. “Behave yourselves,” she shouted, regaining her composure.

She looked back at Ernest who was unloading their suitcases, placing them on the laterite ground. She walked over, balanced Tsotsoo and the snakeskin bag in one hand and picked up a suitcase with the other.

The children cantered about.

“Stop running!” she said, striding forward.

The neem tree just outside Papa Yaw’s compound was still standing.Lizzie looked at the tree, its leaves rustling. Its lemon-green neem fruits hung like little pearls from the branches. She shivered.

She stared at the entrance. The last she’d seen of it was when Papa Yaw walked back to her shadowed suitor. She walked into the compound trailed by her family.

Two girls, about Akua Afriyie’s age, sat across from each other, their legs spread out, empty tomato paste cans gathered between their thighs. They were now staring at Lizzie and her family.

“Is Mama Efua in?” Lizzie asked.

They didn’t respond. One of the girls, in a yellow checked dress, stood up. Cans fell from her dress and clanged against the ground. She ran into Efua Serwah’s hut, behind an orange-print curtain. Lizzie looked back at Ernest. His eyes were encouraging. Even the children were standing still, as if they too understood what this moment meant.

Dark chocolate fingers parted the curtain. Out stepped Efua Serwah. She stood tall, her frame still slender. Her skin was tauter against her bones, yet in that tautness age was spelt like the growth rings in the bark of a tree. Her eyes seemed tired. Her hair was tied with black thread that didn’t mask her grey tresses. Efua Serwah seemed to be studying the group in front of her. She looked at Lizzie, her eyes flashing briefly with recognition. She went on, studying each member of the family. Her eyes reddened, tears ran from the corners of her eyes. Lizzie turned to give Ernest the baby. She walked toward her mother, who had now placed her right hand over her mouth. Lizzie wrapped her arms around Efua Serwah’s waist.

“Thank you, God!” Efua Serwah said quietly. She now embraced Lizzie, her arms rubbing her back. She leaned back, kissed Lizzie on both cheeks. Lizzie was also crying.

“Daddy, why is mummy crying?” Lizzie heard Naa Tsoo ask Ernest.

Ernest shushed her. Lizzie turned around, waving her hand in front of her face. “Come say hello to Mama Efua,” she said. All four children ran forward and wrapped their arms around Efua Serwah’s legs.

“They are beautiful,” Efua Serwah said, sucking the phlegm that was stuck in her throat. “And this must be your husband.” She beckoned him toward her. Ernest gave Lizzie Tsotsoo. Efua Serwah hugged Ernest. “Welcome, my son,” she said.

“Where’s Papa Yaw?” Lizzie asked, looking around the compound.

“He’s out somewhere,” Efua Serwah said, taking Tsotsoo out of Lizzie’s arms. “What will you drink? Some palm wine? Oh! Let’s get some stools,” Efua Serwah said to the girl who’d called her out.

“Akua, go help her,” Lizzie said. Akua Afriyie reluctantly trudged behind the girl who could be her cousin or auntie. “Who’s the girl?” she asked Efua Serwah.

“Owusua?” Lizzie felt a sharp pang. She wished she hadn’t asked. “That’s Mama Ama’s granddaughter,” her mother said. Of Papa Yaw’s other wives, Mama Ama was the one Lizzie liked the least. She was always competing with Mama Efua, who was first wife. “I’ve been dreaming about this day since April 1954,” Efua Serwah said. “The only way I could survive was knowing you were fine from the letters you wrote Asantewa. How is she?”

“She’s started a business. She’s doing very well.” Lizzie wasn’t going to tell her about the empty shelves. That life in Accra was hard. That getting people to spend money was what both Asantewa and Ernest were battling with. Tsotsoo yawned widely. Her mouth had barely closed when she reopened it in a loud cry, showing ridged pink gums.

“She’s hungry,” Efua Serwah said, handing her back to her mother.

Lizzie pulled her breast over her boubou’s low neckline and put her nipple in Tsotsoo’s mouth.

“Owusua,” Efua Serwah said. “Go buy one bottle of palm wine and six coca colas.”

“Yes, Mama Efua,” Owusua said, dragging Akua Afriyie by her wrist. Naa Tsoo stood up and ran behind Akua Afriyie and Owusua. The boys sat on the ground by the other girl playing with cans.

“Wame, Wame!” Ernest Jr. said. “I want some.” He pointed at the cans.

Lizzie laughed. At first she wanted to tell them to get off the filthy floor. But, she remembered this is where her beginnings were. She had played on that same ground. This was who she was.

Ernest unzipped one of the smaller suitcases and lifted its flap. It landed in the dust. “Something small,” he said, removing boxes of chocolates, tea, soaps and fabric. He handed Efua Serwah a box of tea.

“This is too much,” Efua Serwah said, her eyes clouding over with tears. “Thank you.”

When Lizzie had fed Tsotsoo, she stuffed her breast back under her boubou. “What’s new in Adukrom No. 2?” she asked.

“A lot! Remember Koo Manu?” Lizzie nodded. “He died last year,” she said. “His family didn’t have the money to have a proper funeral. Papa Yaw had to loan them money.” Papa Yaw had enough money to lend to someone? “All the young girls are married,” Efua Serwah went on. “Remember the Aduhene’s last wife?”

“The young one?”

“Yes. She left him. I think she moved to Accra too.” Efua Serwah touched her aquiline nose, rubbed the pointed end with her thumb and index finger. She always did that.

“What did the Aduhene do?”

“The man is a fool!” Efua Serwah whispered. “He married again! And he beats the girl like no one’s business.” Lizzie winced. Papa Yaw beat you too, she thought. “And you? How’s Accra?”

“The pictures,” Lizzie said to Ernest, who took an album out of a pocket of the suitcase. He gave them to Efua Serwah.

“Oh, beautiful,” she said.

“This was the first picture we took together as a family,” Lizzie said. “We were having a party that day and I had a professional photographer come over.”

As Efua Serwah flipped through the photos, Lizzie heard shuffling at the entrance. She looked up and saw Papa Yaw. His hair was completely grey, except for a bald shiny spot above his forehead. She didn’t remember him being bald.

“Ei, you’re still alive,” he said, his eyes darting from Lizzie to Ernest to the boys playing on the ground.

“That’s no way to welcome your daughter,” Efua Serwah said.

“Sorry, for my rudeness,” he said. “Welcome.” He walked to Ernest and shook his hand. He shook Lizzie’s limply and walked into his hut.

“We can drive to Kumasi to stay in a hotel if we’ll be a bother,” Lizzie said.

“Ah, Lizzie-Achiaa! Don’t tell me that because you live in Accra, you’re now an obroni. Family stays here.”

Papa Yaw came back out. “Your husband can sleep in my room.” Lizzie’s eyes popped open. She looked at her mother and wondered if Papa Yaw wasn’t hatching some evil plan.

“Thank you, sir,” Ernest said.

“What a proper family,” Papa Yaw said, chuckling. “Sir! Lizzie-Achiaa married an obroni,” he said to his wife. He chuckled back to his room.

During dinner, the family sat on stools in three groups, around the three wives. In Mama Efua’s circle, Ernest sat by Papa Yaw, the boys to his left. Owusua had hijacked Akua Afriyie, and of course, Naa Tsoo sat by her. Lizzie didn’t know half the faces in the other circles. She caught Mama Ama looking over every so often. Lizzie licked the spinach stew off her hand. Kwame and Ernest Jr. were bound to get palm oil on their shirts. Stop worrying! she told herself. She looked up. The sky above, already indigo, darkened.

After dinner, she took the children into Efua Serwah’s room. It wasn’t like she remembered. A queen-sized bed had replaced the mat Efua Serwah used to sleep on. On top of a dresser she’d placed dusting powder, shea butter and little bottles of perfume. They didn’t seem to be struggling.

The next day, after their koko and bread, Papa Yaw who’d been whistling since he came out of his room, offered to take them to Opanyin Nti’s.

Papa Yaw, Lizzie and Ernest walked by young girls sweeping through dust with palm frond brooms. The girls stopped as the trio walked by.

“Have you lost something?” Papa Yaw asked them, sucking his teeth. Lizzie wondered what her father had against young girls. He just always seemed to be inordinately rude to them.

They arrived at Opanyin Nti’s hut. It was exactly the way she remembered it—woven from palm fronds and strong branches blown off trees during thunderstorms. She remembered running there when Owusua fell to the ground, writhing. How she’d met Bador Samed for the first time. How she was instantly intoxicated in his strangeness and foreignness.

“Opanyin!” Papa Yaw shouted.

The medicine man walked out. Like his home, he hadn’t changed. Sure, his hair was entirely grey, but his face looked, if anything, younger than before. He moved about stridently, with verve and with a vibrancy that none of the older people in the village possessed.

“Who is this?” he said, smiling broadly. “When did you come back?” He looked at Lizzie, shaking Papa Yaw’s hand. He moved on to shake Lizzie and Ernest’s hands.

“Yesterday,” Lizzie said.

“Come in, come in,” he said, arranging four stools in his cool hut. “So?” he asked.

“Opanyin,” Lizzie said, “this is my husband Ernest. He’s been asthmatic for so many years. We’ve tried all sorts of drugs, but nothing’s worked …” She looked at Ernest.

“Yes,” Ernest said, “two months or so ago, I had a really bad attack. We were hoping you could help,” he said, fiddling with the top button of his shirt.

“All right,” Opanyin Nti said, “I’d like a word with Ernest here.”

“We’ll wait outside,” Papa Yaw suggested.

“No, no. We’ll just go into my inner room.” Opanyin Nti said, springing up from his stool, leading Ernest into the darkened room.

Papa Yaw and Lizzie hadn’t been alone yet. Now he looked at her, a smirk raising the right corner of his lips.

“Lizzie,” he whispered, “who is this Ga man who can’t breathe properly? Is this the best you can do? Some man with some disease?”

Lizzie bit her tongue. The man always had to find a way to dampen her spirits. “Papa Yaw, please don’t start,” she said. This man with a disease has built me a house you’ll never see, she thought. “We have five healthy children. We live comfortably. He has a good job,” Lizzie said, wondering why she should be making any excuses. Ernest was better than any suitor Papa Yaw would have offered her.

Opanyin Nti and Ernest came out fifteen minutes later.

“We’ve talked about Ernest’s health history,” Opanyin Nti said. “I have a remedy.”

“Good,” Lizzie said, clapping her hands, even though she was doubtful.

“I have to make soup, though, and it will take time. Come back this afternoon.”

After they’d gone back to the compound, Papa Yaw went into his hut and came back out.

“Can I have a word with you, Lizzie?” he asked, while Efua Serwah played with her grandchildren. Ernest sat by her. Lizzie wondered what that could be about, hopefully not about Ernest.

“Of course, Papa,” she said. “I’ll be back,” she said to her mother and husband.

Papa Yaw didn’t say anything as he strode ahead of her. She looked around as they passed by houses that stood on ground that used to be bush. She realized they were walking toward his farm. Was he going to ask her for money? That would be her ultimate victory. When she saw his farm, she was even more convinced. It was a shambles. Long dried grass covered most of the area. Only half the number of cocoa trees that they’d planted in the fifties seemed to be left standing.

“What happened here?” she asked him.

“Oh, don’t worry about the farm,” he said.

“But, Papa Yaw, how do you get money?”

“I’ve retired,” he said. “My children take good care of me.” He knew how to get her goat—she hadn’t sent him a pesewa since she left. “But that’s not why I brought you here. I have something to get off my chest.”

“What’s this about?” Lizzie asked, beginning to get worried the man might start beating her, even though this time she would definitely have the upper hand. She could smell palm wine on him. He’d probably imbibed so much of the stuff that it coursed through his veins now.

“You’ve managed to do well for yourself,” he said. Lizzie looked at him incredulously. Had she heard him right? “I have to tell you …” he faltered. “All those years ago,” he said, his eyes distant, “I wanted you to marry someone I chose, but you made the right decision. Even though your husband can’t breathe well, he seems like a gentleman. Mo! You have a beautiful family.”

She couldn’t believe that her father had actually uttered those words. This moment was what she’d come back to Adukrom No. 2 for. They walked back to Papa Yaw’s compound, where Ernest stood at the entrance, looking out for them.

“There you are!” Ernest said. “I’m sure Opanyin Nti has finished brewing his soup.”

Lizzie smiled. “I was catching up with my father.” Papa Yaw seemed to have a sad expression on his face. How could saying something nice about her make him so sad? Lizzie wondered. He was too proud.

They walked to Opanyin Nti’s. Lizzie walked in a daze—having her father’s opinion of her be so high was, really, what she’d been living for. Now, there was only one problem left for her to solve.

In Opanyin Nti’s hut, the medicine man offered them seats. He brought out a steaming pot of soup. It smelled delicious. She watched as he took a tortoise shell, turned it over and ladled the orange soup into the shell.

“There’s turtle oil in the soup,” Opanyin Nti said. “Drinking from this bowl will cure you.” He passed the shell to Ernest, who took a sip and gagged. “Drink up,” Opanyin Nti said, as if Ernest was a child refusing dinner.

Ernest gulped down all the soup in one go. After barely a minute, he retched violently. He waved his hand under his chin. Lizzie and Opanyin Nti helped him outside the hut where he threw up all the soup, the koko he had eaten that morning, as well as bits and pieces Lizzie couldn’t make out. What had he been eating in her absence?

“Is this working?” she asked the medicine man.

“Exactly like it should,” he said. “Take him home, let him rest. He’s going to vomit the entire day. Tomorrow bring him back for more soup. We’ll do this for three days.”

“Yes, Opanyin,” she said. Ernest continued to heave, his whole torso shaking. This better work, Lizzie thought.

*

On the fourth day after the turtle soup treatment, Ernest walked out of Papa Yaw’s hut, beaming. It was the first day since imbibing Opanyin Nti’s concoction that Lizzie had seen him smile. He wasn’t retching or holding onto his abdomen. She was amazed at how this was also the first time a healer had subdued his spirit. She remembered all the times in Korle Bu, when he’d just end up in giggling fits.

“You look well,” she said.

“Have never felt better,” he said. “I can breathe without a wheeze getting in the way.” Wonders never cease! Lizzie thought. She had been convinced Opanyin Nti’s medicine wouldn’t work.

“Let’s take a walk then,” she said. She walked into her mother’s room, where she found Efua Serwah lying on her bed, surrounded by her grandchildren. “Junior!” Lizzie shouted, as she saw him twiddle his grandmother’s big toe.

“I’m their nana,” Efua Serwah said.

“If you’re not firm with these children, they’ll bully you,” Lizzie said. “You should see how they walk all over Asantewa. I’m going for a walk with Ernest.”

“All right,” Efua Serwah said.

“Bye!” the children chorused.

She hooked her arm in Ernest’s as they left Papa Yaw’s compound.

“Where are we going?”

“I’m going to show you my favorite place in the whole world.” And we’re going to have a tête-� -tête, Lizzie thought. She was going to deal with her other problem.

“I’m honored, Mrs. Mensah,” Ernest said.

They walked behind the compound, on a laterite path.

“All this used to be grass,” Lizzie said. “They get rid of the grass and leave sand that just stains your feet!” She sucked her teeth. She could hear the gargle of the Insu River before they got to it. Nostalgia swam about her.

There it stood. The khaya tree. Her khaya tree. Hers and Bador Samed’s.

“This is it!” she said, pointing up and down the tall trunk. The Insu River bubbled by. It was smaller than she’d imagined it.

“Wow!” Ernest said. “This tree goes up to heaven!”

They settled at the base of the tree, where she and Bador used to have their long conversations, where Lizzie had experienced love for the first time. Of course, Ernest didn’t need to know that.

“Ernie,” she said, “is there anything you want to tell me?”

“Like what? You’re the best wife a man could ask for? Thanks for bringing me here, showing me how great your family is, and for clearing my chest!”

They remained silent. Lizzie hoped Ernest would break down and confess, but he had no idea that she knew, so why would he? A forest bird cuckooed.

“I’m such a city man,” Ernest said. “I love being here, but I miss the smell of pollution and the sound of taxi drivers honking insanely. You must miss the sounds of the forest living in Accra. Trotro mates shouting, market women haggling …”

“Ernest, I have a question and please don’t lie to me,” she said. Ernest looked at her with such a sad look, she wished she wasn’t about to say what she was. “Who’s Gertrude Mensah?”

Ernest choked. “How do you know about Gertrude?”

“Accra is a small place. People talk.”

Ernest scratched his head.

“No playing around, just the truth,” Lizzie said.

“That’s strange. Only one or two people know about her,” he said quietly. Lizzie wasn’t going to tell him she broke into his briefcase. “She’s my daughter.”

“That much I knew. When were you planning to tell me?”

Ernest, now looking at the damp loam, said, “She was born before we met. Her mother is German. I just didn’t want to mix flavors.”

“Mix flavors? Ernest, you should have told me before we got married. I wouldn’t have said no just because you already had a child. A part of me thinks that you haven’t told me because you’re still seeing her mother.”

“No, no,” Ernest said, still looking down.

Lizzie wasn’t convinced. “You are divorced from her mother, aren’t you?”

“Oh, yes, before we got married. She was my boss’s daughter.”

“The Lutterodt guy?”

“Yes.”

“Did you feel like you had to marry his daughter because of all that he’d done for you?” Lizzie asked, thinking that if Ernest said yes to that question, Gertrude and her mother wouldn’t be as important in Ernest’s life. They were just there to return a favor.

“No. We genuinely loved each other. When I met her in 1951, she was the first white woman I was ever attracted to. But you know, you might love someone dearly, but you just can’t live together. You just don’t work. That’s what happened to us.”

That was far from the answer Lizzie was hoping to hear.

“Do you still love her?” she asked.

“Lizzie!”

“Answer me!”

“Lizzie,” Ernest’s voice pleaded.

“You at least owe me an answer,” she said.

“It’s not easy to stop loving someone. Especially when you have a bond like a child. But I love you so much more,” he said.

She was not happy.

“So you were planning on keeping your daughter a secret forever?”

“Honestly,” he said, exhaling, “I was. I thought I could keep both worlds separate.”

“Ernie,” Lizzie said, “I hate to say this, but she’s going to want to know where her father is from. Everyone has two histories. And keeping her away from here is depriving her of half her life story. She has all these crazy sisters and brothers. One who cannot pronounce a single word properly, but insists on talking. Another who insists on fighting with me every opportunity she gets.”

“What you say is true….” Ernest said, smiling.

“If you want to bring her to Ghana ever, she can stay with us.” Ernest looked at Lizzie. They hugged each other, under the khaya tree, the tree that seventeen years ago spelled a different destiny for Lizzie.

Read Per Ankh Publishers’s description of Harmattan Rain.

Copyright © 2008 Per Ankh Publishers/Ayesha Harruna Attah No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher or author. The format of this excerpt has been modified for presentation here.