1 Books Published by Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City on AALBC — Book Cover Collage

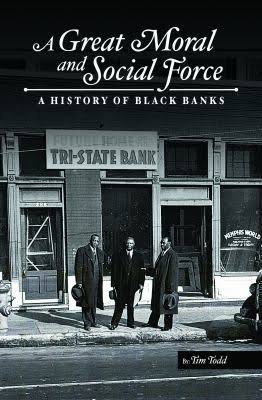

A Great Moral and Social Force: A History of Black Banks

A Great Moral and Social Force: A History of Black Banks

by Tim ToddFederal Reserve Bank of Kansas City (Jan 03, 2022)

Read Detailed Book Description

Both and printed and digital versions of this book is available for free!

• Downlaod a Free Digital (pdf) Copy of the Book

• Fill out This Short Form to Get a Free Printed Book

Many Americans are unaware of the history and challenges Black banks, in the South and Midwest, faced during the late 19th and 20th centuries.

In the Kansas City Fed’s new book, A Great Moral and Social Force: America’s First Black Banks, executive writer Tim Todd focuses on the stories of Black banks in five cities: Richmond, Va.; Boley, Okla.; Chicago, Ill.; Memphis, Tenn; and Detroit, Mich. These cities were shining examples of Black wealth and success, and the book explores factors that contributed to the demise of Black banks at the peak of their success. Todd also provides historical context and analysis about why the dismantling of Black banks has played a central role in the hurdles many Black people face today regarding financial security and amassing generational wealth.

Rather than presenting a comprehensive history of Black banking, the goal of A Great Moral and Social Force: America’s First Black Banks is to move across eras and examine some of the communities where banks played a dual role in establishing both economic opportunity and social equality. These banks were not purely a financial endeavor or a business opportunity but more importantly, were created with the primary mission of public service in mind. Community banks were catalysts in helping families and individuals establish businesses, buy homes, and pay for an education that could open the door to opportunity. In their role as pillars of the community, Black banks were involved in some of the most important race relations events in American history, and during the struggle for civil rights, Black bankers were among the leaders in the Black community who spearheaded the fight for social justice.

The stories from these communities include:

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond, after the Civil War, was the cradle of Black capitalism and especially Black banking. The city’s Jackson Ward neighborhood earned national recognition as “Black Wall Street” and the “Harlem of the South.” A key figure in Jackson Ward was Maggie Lena Walker, the first woman of any race to be a bank president.

As the first Black female bank president in the United States, Maggie Lena Walker became something of a celebrity and is today the most well-known among the nation’s earliest Black bankers.

Boley, Oklahoma

More than 50 Black towns and settlements were established in Oklahoma before the 1920s, and perhaps the most successful of these was Boley. At a meeting of the Business Men’s League of Boley, the Farmers and Merchants Bank of Boley was organized in 1906 with plans for $15,000 in capital stock. Among its founders were T. M. Haynes and D. J. Turner. In late 1907, the community added another bank, Boley Bank and Trust, founded by E.L. Lugrande. In early 1910, it merged with Farmers and Merchants Bank. By 1921, the First National Bank of Boley opened and became the first Black-owned bank with a national charter. Among its founders were J.D. Nelson and Sebrone Jones King.

Memphis, Tennessee

At the time of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s "I’ve Been to the Mountaintop" speech, Tri-State Bank, founded in 1946 under the leadership of Joseph Edison Walker and his son A. Maceo Walker, was already well-known and respected within the civil rights movement. When Tri-State opened, it was the first new Black bank in the United States since the mid-1930s and the first Black bank in Memphis in nearly 20 years. Notably, Tri-State opened near the corner of Beale Street and Fourth Avenue, a location used by its Memphis predecessor. Within the first year, there were around 1,800 accounts held by local and out-of-town depositors including some whites, with nearly $1.5 million in total deposits. Within its first 10 years, the bank claimed it had made more than $10 million in mortgage loans on homes for more than 2,000 Black families.

The publication of books like A Great and Moral Social Force brings a new perspective to the economic history of underrepresented communities, reaffirms the significance of Black economic enclaves, and serves as a blueprint for communities attempting to obtain financial success under challenging circumstances.

John Williams’ success as an automobile mechanic in Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood (eventually known as “Black Wall Street”) provided him and his wife Loula with the capital to construct two of the community’s landmark businesses — the Williams’ Confectionary and the 800-seat Dreamland Theater. Their story is one of many highlighted in A Great Moral and Social Force: A History of Black Banks. These businesses were ultimately destroyed during the Tulsa Race Massacre.

John Williams’ success as an automobile mechanic in Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood (eventually known as “Black Wall Street”) provided him and his wife Loula with the capital to construct two of the community’s landmark businesses — the Williams’ Confectionary and the 800-seat Dreamland Theater. Their story is one of many highlighted in A Great Moral and Social Force: A History of Black Banks. These businesses were ultimately destroyed during the Tulsa Race Massacre.