Perihelion + Aphelion explanation

Event created by richardmurray

Event details

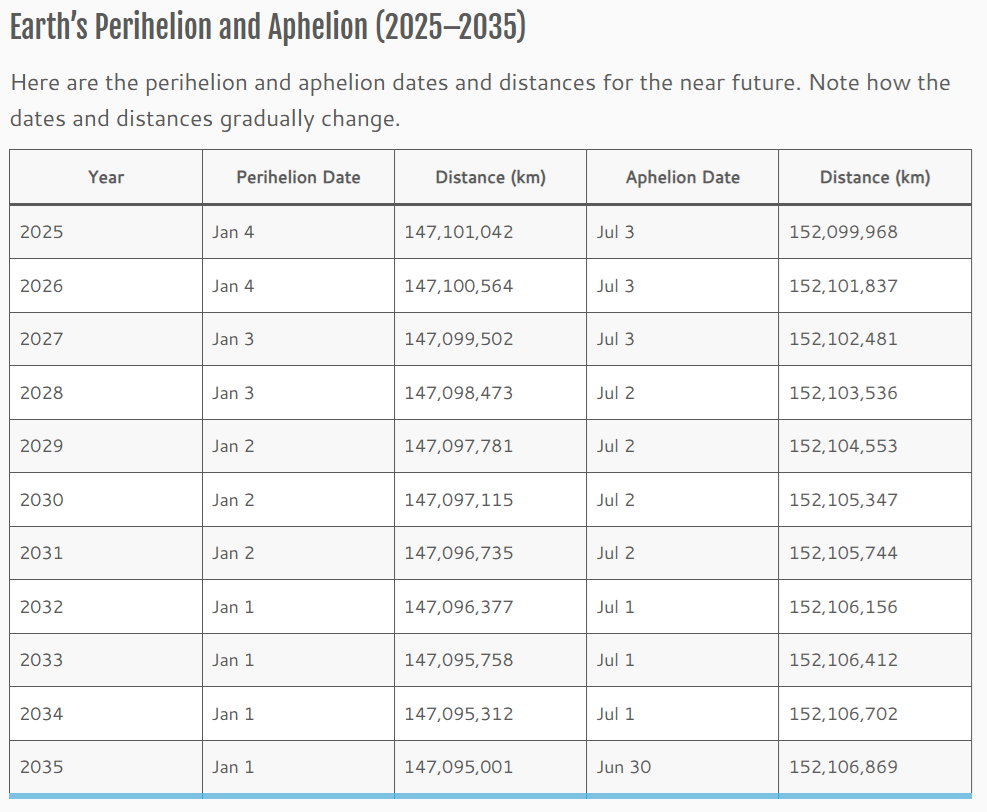

This event began 01/01/2026 and repeats every year forever

DATES or GRAPHIC

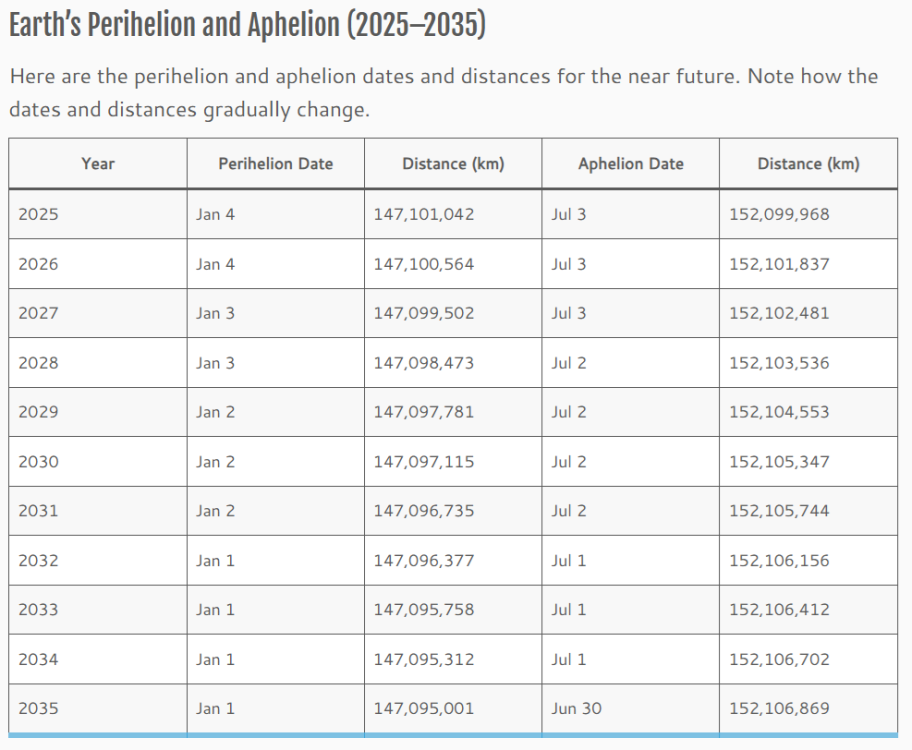

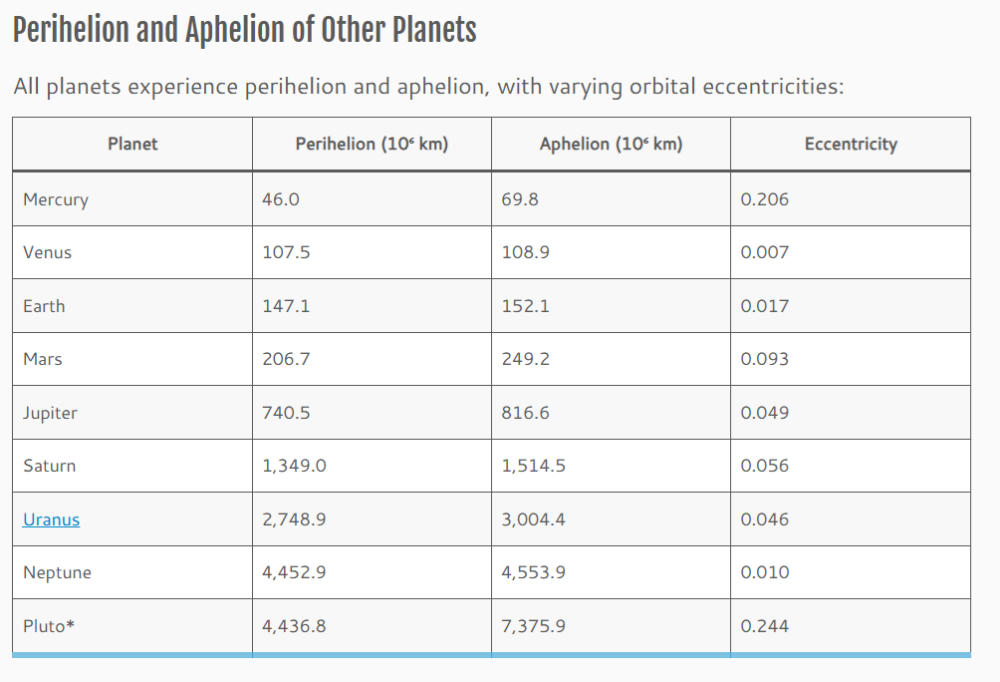

Note: Distances are approximate and calculated from JPL ephemeris data.

Pluto is a dwarf planet. Its eccentricity causes it to cross Neptune’s orbit.

TEXT

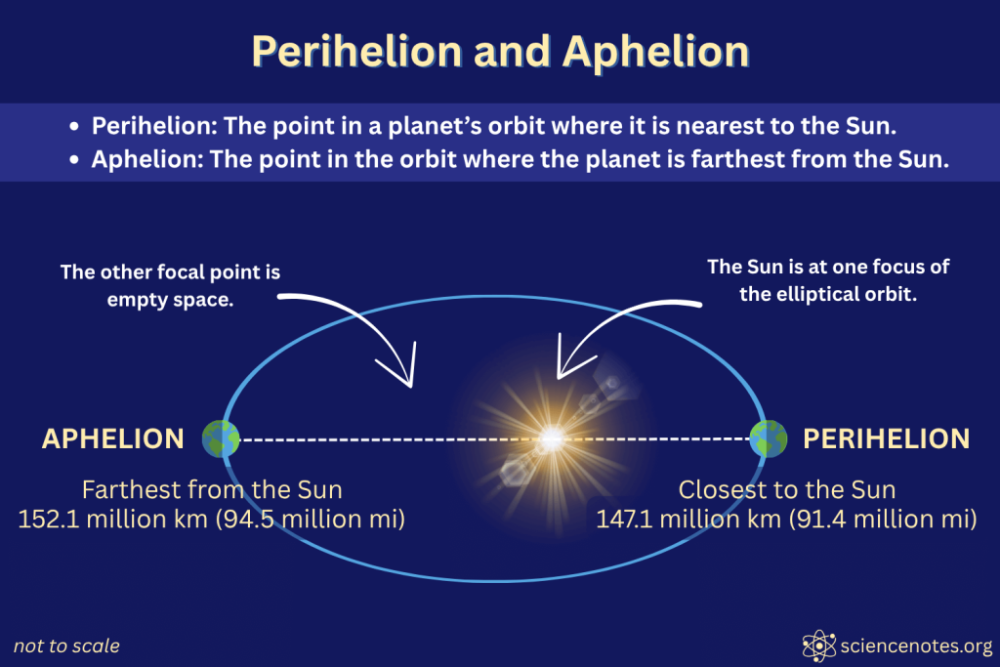

In astronomy, perihelion and aphelion are the two extreme points in Earth’s elliptical orbit around the Sun. These terms also apply to any object orbiting the Sun or another star. Perihelion is the point where the object is nearest to the Sun, while aphelion is when it is farthest away. Earth’s orbit is not a perfect circle but a slightly flattened ellipse, with the Sun at one of the foci of the ellipse (not the exact center), so the distance between Earth and the Sun varies slightly over the year.

Although these points influence the amount of solar radiation Earth receives, they are not responsible for the seasons. Seasons arise from Earth’s axial tilt, not its distance from the Sun. However, the elliptical shape and the timing of perihelion and aphelion do subtly affect seasonal duration and intensity.

Apsis is the general term for orbital extremes (includes perigee and apogee for Earth-orbiting objects).

What Are Perihelion and Aphelion?

Johannes Kepler coined the terms “perihelion” and “aphelion” to describe the orbits of planets around the Sun.

Perihelion: The point in a planet’s orbit where it is nearest to the Sun.

Aphelion: The point in the orbit where the planet is farthest from the Sun.

These distances are measured from the center of the Sun to the center of the planet. The Earth is about 147.1 million km (91.4 million mi) from the Sun at perihelion and about 152.1 million km (94.5 million mi) at aphelion.

Etymology

Perihelion comes from the Greek peri- (near) and helios (Sun).

Aphelion comes from apo- (away from) and helios (Sun).

Both terms use the suffix -helion from the Greek word for Sun and are specific to objects orbiting the Sun. The more general term, apsis, refers to extreme points in any orbital system.

Apsis and Earth’s Orbit

Although Earth’s orbit is elliptical, the Sun is not located at the center of the ellipse. Instead, it occupies one of the two focal points of the orbit, while the other focus lies in empty space. This means Earth–Sun distance changes slightly throughout the year, giving rise to perihelion and aphelion.

The line of apsides connects the perihelion and aphelion of an orbit. For Earth, the apsides shift over time due to gravitational interactions with the Moon and planets, causing apsidal precession.

Although Earth’s orbit is almost circular, the slight elliptical shape leads to small but measurable differences in solar distance during the year. These points of apsis don’t align with solstices or equinoxes due to this precession.

Eccentricity and Orbital Shape

Eccentricity (e) describes how much an orbit deviates from a perfect circle:

A circle has eccentricity e = 0.

Ellipses have 0 < e < 1.

Earth’s current orbital eccentricity is about 0.0167, meaning it’s very close to circular. In graphics, illustrators exaggerate the ellipse to convey that the orbit is not a perfect circle.

Over tens of thousands of years, Earth’s eccentricity varies due to gravitational interactions, influencing climate cycles (Milankovitch cycles).

Do Perihelion or Aphelion Coincide With Solstices or Equinoxes?

Currently, perihelion occurs shortly after the December solstice, and aphelion occurs after the June solstice. The proximity of perihelion to the Northern Hemisphere’s winter solstice slightly shortens winter and lengthens summer.

Due to apsidal precession, these dates shift by about one day every 58 years. Around the year 1246, perihelion occurred on the December solstice. In about 10,000 years, it will coincide with the March equinox.

Apsis and the Seasons

While it’s common to assume that Earth’s varying distance from the Sun causes the seasons, this is not the case. The primary driver of seasonal change is Earth’s axial tilt of about 23.5°, not its distance from the Sun. However, the location of the apsides (perihelion and aphelion) does have subtle effects on seasonal length and solar intensity.

At perihelion, Earth is closest to the Sun and moves faster in its orbit due to the increased gravitational pull. As a result, the Northern Hemisphere winter is slightly shorter (about 89 days), while summer is slightly longer (about 93 days). The opposite occurs in the Southern Hemisphere, which receives more intense solar radiation during its shorter summer because of Earth’s proximity to the Sun at that time.

The uneven distribution of land and ocean between the hemispheres enhances this asymmetry. The Southern Hemisphere has more ocean, which moderates temperature changes, while the Northern Hemisphere has more landmass and experiences greater seasonal variation despite receiving slightly less sunlight at aphelion.

Apsidal Precession and Milankovitch Cycles

Over thousands of years, the orientation of Earth’s orbit gradually shifts due to apsidal precession, a slow rotation of the line connecting perihelion and aphelion. Currently, Earth reaches perihelion shortly after the December solstice, but this alignment drifts forward through the calendar over time.

This precession completes a full cycle approximately every 112,000 to 130,000 years. As a result, the timing of perihelion slowly changes in relation to the equinoxes and solstices. When perihelion occurs during a Northern Hemisphere summer, the hemispheric seasonal differences are minimized. When it aligns with winter, the seasonal contrast is enhanced.

Apsidal precession is one of the three key orbital variations described by Milutin Milankovitch, which influence long-term climate cycles on Earth:

Eccentricity – the shape of Earth’s orbit (100,000-year cycle)

Axial tilt (obliquity) – the angle of Earth’s axis (41,000-year cycle)

Precession – the wobble of Earth’s axis (26,000-year cycle)

Together, these Milankovitch cycles affect Earth’s climate patterns and have been linked to the timing of ice ages and interglacial periods.

Perigee and Apogee: Apsis Terms for Earth-Orbiting Bodies

The -helion suffix refers to a body orbiting the Sun, while the -gee suffix refers to the apsis of a body orbiting Earth.

Perigee: Closest point to Earth in the orbit of a satellite or the Moon.

Apogee: Farthest point from Earth.

These are the equivalents of perihelion and aphelion for orbits around the Earth.

For example:

The Moon reaches perigee at about 363,300 km and apogee at about 405,500 km.

These distances affect apparent size (e.g., supermoons at perigee) and gravitational effects.

Comparison With Binary Star Systems or Exoplanets

The concept of apsis also applies to planets orbiting other stars or star system. For exoplanets (planets outside our Solar System), the terms periastron and apastron are the general terms for orbiting stars. In binary star systems, the terms periastron and apastron describe the closest and farthest points in the orbit of one star around another.

Understanding their orbital eccentricity and distance variation aids in evaluating the planet’s habitability, particularly if large differences in distance lead to extreme temperature swings.

Some exoplanets, known as eccentric Jupiters, have highly elliptical orbits that cause drastic changes in their environment as they swing close to and far from their stars. In contrast, planets with low eccentricity and stable distances from their stars are more likely to support Earth-like conditions.

In summary, astronomers use periapsis terminology that describes the central body:

Perihelion/aphelion – around the Sun

Perigee/apogee – around Earth

Periastron/apastron – around another star

Perijove/apojove – around Jupiter

Kepler’s Laws in Context

Kepler’s Laws of Planetary Motion describe the mechanics of elliptical orbits, including the behavior of perihelion and aphelion:

Law of Ellipses

Each planet orbits the Sun in an ellipse with the Sun at one focus (not the center). This explains why Earth has both a closest and farthest point in its orbit.

Law of Equal Areas

A line joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas in equal time. This means Earth moves faster at perihelion and slower at aphelion, altering the apparent speed of the seasons.

Law of Harmonies

The square of a planet’s orbital period is proportional to the cube of its semi-major axis:

T2 ∝ a3

This law relates orbital duration and distance, and helps astronomers compare orbits across the Solar System.

Kepler’s laws form the foundation for Newton’s laws of motion and universal gravitation, and they remain essential for calculating orbits, planning space missions, and understanding the celestial mechanics of planets and moons.

FAQs About Perihelion and Aphelion

Q: Does perihelion make Earth hotter?

A: No, seasons are controlled by axial tilt, not proximity to the Sun. However, perihelion does slightly increase solar radiation, particularly in the Southern Hemisphere.

Q: Why isn’t Earth warmest at perihelion?

A: The Northern Hemisphere, which has more landmass, tilts away from the Sun during perihelion. Land heats and cools more rapidly than oceans, so Southern Hemisphere summers are slightly milder.

Q: Is Earth speeding up or slowing down at perihelion?

A: Earth moves faster at perihelion and slower at aphelion, as predicted by Kepler’s second law (equal areas in equal time).

Q: Can perihelion and solstice happen on the same day?

A: Yes, but it’s rare. The last near-alignment was in 1246 CE. They drift apart due to apsidal precession.

Q: Is the orbit getting more or less eccentric?

A: Eccentricity varies cyclically (~100,000-year cycles). Currently, Earth’s orbit is becoming slightly less eccentric.

Q: What is the difference between perihelion and perigee?

A: Perihelion refers to being closest to the Sun. Perigee refers to being closest to Earth in a satellite’s orbit.

References

D’Eliseo, Maurizio M.; Mironov, Sergey V. (2009). “The Gravitational Ellipse”. Journal of Mathematical Physics. 50 (2): 022901. doi:10.1063/1.3078419

Luo, Siwei (2020). “The Sturm-Liouville problem of two-body system”. Journal of Physics Communications. 4 (6): 061001. doi:10.1088/2399-6528/ab9c30

Michelsen, Neil F. (1982). The American Ephemeris for the 21st Century – 2001 to 2100 at Midnight. Astro Computing Services. ISBN 0-917086-50-3.

REFERAL

https://sciencenotes.org/perihelion-and-aphelion-closest-and-farthest-points-from-the-sun/

User Feedback

There are no reviews to display.