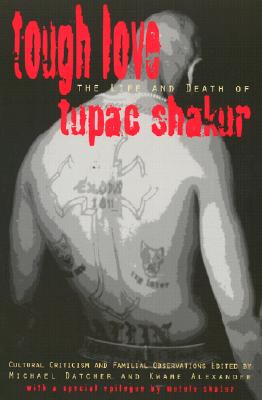

Tough Love: Cultural Criticism & Familial Observations on the Life and Death of Tupac Shakur

by Kwame Alexander and Michael Datcher

BlackWords (Dec 15, 1996)

Nonfiction, Paperback, 160 pages

More Info ▶

Description of Tough Love: Cultural Criticism & Familial Observations on the Life and Death of Tupac Shakur by Kwame Alexander and Michael Datcher

Tough Love Excerpts

Sideliners will suggest, on radio shows, and Entertainment Tonight, he "had it coming" or chose that lifestyle." On the streets of New York, some will even tell you they are glad he’s gone. I believe, that for Pac, living intensely was never an option. We were born the same year and poor and came of age in the most violent era our people have known. Pac didn’t have a death wish so much as an understanding (and with it came an eerie peace) that life would be short. (Hence his funeral instructions on "Life Goes On.") In 25 years, he made four albums, and as many films. His mercurial mind was rapid and restless, and in a single sentence he could be utterly profound or stunningly inane. There are those who will live long, smug, mediocre lives and matter only to their house pets. They will never understand Pac, who made every moment matter.—Dream Hampton

WALKING THE TIGHT ROPE:

The Art, Reality and Impact of Tupac Shakur

By Bakari Kitwana

The recent murder of Tupac Shakur is a great tragedy and a waste of a young, promising life. Shakur at only 25 years-old had come to represent a volatile mixture of youthful energy, exuberance, arrogance, self-confidence and, at times, foolishness. He represented possibility on the one hand and self-destruction on the other. What mustn’t be overlooked as the Hip-Hop Community mourns his loss is that there are many young Black men like Tupac Shakur who although less well-known and less financially secure, are equally caught up in self-destructive lifestyles. Due to a great deal of misinformation and a changing economy, their numbers are growing, even as they are being wiped off the planet everyday. Herein lies one of the greatest challenges facing the Black world in the 21st century: how do we combat the dominant public image of young Black men that has largely been produced by mass media? Tupac Shakur’s life and death is a microcosm of the larger picture. Do we dare peer into it?

Rap music is no longer simply the local, communal form of entertainment that it was at its inception in the early 1970s. And even the thriving commercial entity it became by the late 1980s — as gangsta rap moved from the margins of hip-hop culture to the center — has already been transformed. Despite the various changes in the rap industry over the last six years, there has been at least one constant: rap artists who have enjoyed international fame and platinum sales due to their ability to shock with Black pathological horror stories and thereby entertain. Although some advance a musical art form whose artistic, political and social implications have yet to be thoroughly critiqued or completely understood, rap music’s firmly entrenched dual role as a corporate business and cultural art form demands that artists primarily project stereotypes of young Black men as reality. Within the music industry the belief persists that images of Black men as gun-toters, drug users, drug sellers, irresponsible fathers, and violent, misogynists are not only authentic representations of Black men, but Black men at their best. And although the rap art form grew out of Black culture, hip-hop culture in the mid- 1990s more often mirror a dog-eat-dog street culture that destroys more lives that it strengthens. As a major rap artist who had an affinity for acting (see Bishop in Juice and Birdie in Above the Rim), Tupac often walked the tightrope between the art and the reality…

Bakari Kitwana is the Political Editor of The Source: The Magazine of Hip-Hop Music, Culture, and Politics, and the Author of The Rap on Gangsta Rap. He is also a contributor to National Public Radio’s All Things Considered and lectures on rap music and Black youth culture at colleges and universities across the country.

TUPAC AND THE POLITICS OF "FUCK IT"

By Esther Iverem

Grab your Glocks (guns) when you see Tupac.

Call the cops when you see Tupac…

You shot me but ya punks didn’t finish.

Now you’re about to feel the wrath of a menace

…You know who the REALNESS is

—Tupac Shakur From Hit "Em Up

If you spent any time at all around Tupac, you saw how easy it was for him to let a raised middle finger lead him through the world. Whether he was proclaiming to me in an interview that he stays perpetually strapped and high on marijuana, or spiritedly waving a bottle of malt liquor for the camera on the "California Love, Part II" video, his most consistent image was that of a man doing as he pleased, living life by his own rules. "Fuck it," the rich young man seemed to say. And if you didn’t like it, well then, "fuck you too."

Most of us growing up black in America can identify in a particular way with the quick, bottom-line toughness that sentiment implies. It makes us feel so powerful in a society that has always raised its middle finger to us. This feeling of strength—and don’t we need to feel strong, with every in-your-face Shaquille O’Neal dunk—is one of the reasons so many people identified with Tupac as a real brother. But that affinity mixes what is potentially a positive attitude toward self determination with the worst definitions of that over-used phrase: Keep it Real. At its most meaningful, the phrase urges those in the hip hop nation to remain true to beliefs and rooted in reality. At its worst, it implies that only those things ghettocentric are true and real in black culture. It endorses the use of street ethics to settle, like the willingness to bust a cap in someone if necessary.

Tupac’s death is only the most recent and heart-wrenching reminder that with those definitions of what is real, we are killing ourselves, carting ourselves off to jail or retiring at a young age to wheelchairs.

Esther Iverem writes about arts and culture for the Washington Post and has also written for Essence, New York Newsday and The New York Times. A native of Philadelphia, she is a graduate of the University of Southern California, where she studied journalism and ethnic studies, and Columbia University, where she received her master’s degree in journalism. She lives in Washington, D.C. with her son Mazi.

TUPAC’S SQUANDERED GIFT

by Kenny Carroll

As rapper Tupac Shakur lay dying in a Las Vegas hospital room, commentators, reporters and critics on the left and right were all easily summing up his tragic life as a casualty of a gangsta rapper attempting to live up to his wrong-headed raps. Their analysis lacked the style or economy of my 14 year old son, who sadly proclaimed Tupac "stupid." My own reaction to his death was to think of the Washington poet DJ Renegade’s melancholy libation for the victims of violent crime: This is for the brothers who found out too late, that going out like a soldier means … never coming back.

Shakur’s life and death are now in danger of becoming a cliched object lesson on the dangers of drugs, guns and, unfortunately, hip hop music. But Shakur’s dreary end holds another, perhaps more profound, warning about the role of Black artists in an era of crack cocaine. It says clearly that we cannot afford to be minstrels for dollars or our own dreams of stardom. His death was the lamentable loss of a gifted, misguided, young poet who spoke with insight and energy to his hip-hop world, but who committed the unpardonable sin of using his immense poetic talents to degrade and debase the very people who needed his positive words—his fans…

Kenneth Carroll is Washington coordinator of the WritersCorps program which conducts writing workshops in D.C. neighborhoods. His book "So What! For the White Dude Who Said This Ain’t Poetry" will be published in December.

Melanet -Familial Observations on the Life and Death of TUPAC SHAKUR

Additional Book Information:

- ISBN: 9781888018059

- Imprint: BlackWords

- Publisher: BlackWords

- Parent Company: BlackWords, Inc.

Books similiar to Tough Love: Cultural Criticism & Familial Observations on the Life and Death of Tupac Shakur may be found in the categories below: