35 Books Published by Harvard University Press on AALBC — Book Cover Collage

Who’s Black and Why?: A Hidden Chapter from the Eighteenth-Century Invention of Race

Who’s Black and Why?: A Hidden Chapter from the Eighteenth-Century Invention of Race

by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Andrew S. CurranBelknap Press (Mar 22, 2022)

Read Detailed Book Description

The first translation and publication of sixteen submissions to the notorious eighteenth-century Bordeaux essay contest on the cause of black skin—an indispensable chronicle of the rise of scientifically based, anti-Black racism.

In 1739 Bordeaux’s Royal Academy of Sciences announced a contest for the best essay on the sources of "blackness." What is the physical cause of blackness and African hair, and what is the cause of Black degeneration, the contest announcement asked. Sixteen essays, written in French and Latin, were ultimately dispatched from all over Europe. The authors ranged from naturalists to physicians, theologians to amateur savants. Documented on each page are European ideas about who is Black and why.

Looming behind these essays is the fact that some four million Africans had been kidnapped and shipped across the Atlantic by the time the contest was announced. The essays themselves represent a broad range of opinions. Some affirm that Africans had fallen from God’s grace; others that blackness had resulted from a brutal climate; still others emphasized the anatomical specificity of Africans. All the submissions nonetheless circulate around a common theme: the search for a scientific understanding of the new concept of race. More important, they provide an indispensable record of the Enlightenment-era thinking that normalized the sale and enslavement of Black human beings.

These never previously published documents survived the centuries tucked away in Bordeaux’s municipal library. Translated into English and accompanied by a detailed introduction and headnotes written by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and Andrew Curran, each essay included in this volume lays bare the origins of anti-Black racism and colorism in the West.

Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound

Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound

by Daphne A. BrooksBelknap Press (Feb 23, 2021)

Read Detailed Book Description

An award-winning Black feminist music critic takes us on an epic journey through radical sound from Bessie Smith to Beyoncé.

Daphne A. Brooks explores more than a century of music archives to examine the critics, collectors, and listeners who have determined perceptions of Black women on stage and in the recording studio. How is it possible, she asks, that iconic artists such as Aretha Franklin and Beyonc exist simultaneously at the center and on the fringe of the culture industry?

Liner Notes for the Revolution offers a startling new perspective on these acclaimed figures—a perspective informed by the overlooked contributions of other Black women concerned with the work of their musical peers. Zora Neale Hurston appears as a sound archivist and a performer, Lorraine Hansberry as a queer Black feminist critic of modern culture, and Pauline Hopkins as America’s first Black female cultural commentator. Brooks tackles the complicated racial politics of blues music recording, song collecting, and rock and roll criticism. She makes lyrical forays into the blues pioneers Bessie Smith and Mamie Smith, as well as fans who became critics, like the record-label entrepreneur and writer Rosetta Reitz. In the twenty-first century, pop superstar Janelle Monae’s liner notes are recognized for their innovations, while celebrated singers Cecile McLorin Salvant, Rhiannon Giddens, and Valerie June take their place as cultural historians.

With an innovative perspective on the story of Black women in popular music—and who should rightly tell it—Liner Notes for the Revolution pioneers a long overdue recognition and celebration of Black women musicians as radical intellectuals.

Being Property Once Myself: Blackness and the End of Man

Being Property Once Myself: Blackness and the End of Man

by Joshua BennettBelknap Press (May 12, 2020)

Read Detailed Book Description

A prize-winning poet argues that blackness acts as the caesura between human and nonhuman, man and animal.

Throughout US history, black people have been configured as sociolegal nonpersons, a subgenre of the human. Being Property Once Myself delves into the literary imagination and ethical concerns that have emerged from this experience. Each chapter tracks a specific animal figure—the rat, the cock, the mule, the dog, and the shark—in the works of black authors such as Richard Wright, Toni Morrison, Zora Neale Hurston, Jesmyn Ward, and Robert Hayden. The plantation, the wilderness, the kitchenette overrun with pests, the simultaneous valuation and sale of animals and enslaved people—all are sites made unforgettable by literature in which we find black and animal life in fraught proximity. Joshua Bennett argues that animal figures are deployed in these texts to assert a theory of black sociality and to combat dominant claims about the limits of personhood. Bennett also turns to the black radical tradition to challenge the pervasiveness of antiblackness in discourses surrounding the environment and animals. Being Property Once Myself is an incisive work of literary criticism and a close reading of undertheorized notions of dehumanization and the Anthropocene. Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration

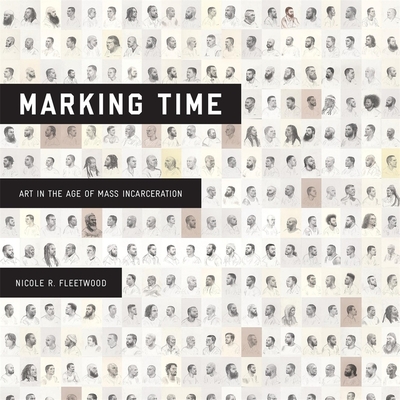

Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration

by Nicole R. FleetwoodHarvard University Press (Apr 28, 2020)

Read Detailed Book Description

- Winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award

- A Smithsonian Book of the Year

- A New York Review of Books “Best of 2020” Selection

- A New York Times Best Art Book of the Year

- An Art Newspaper Book of the Year

A powerful document of the inner lives and creative visions of men and women rendered invisible by America’s prison system.

More than two million people are currently behind bars in the United States. Incarceration not only separates the imprisoned from their families and communities; it also exposes them to shocking levels of deprivation and abuse and subjects them to the arbitrary cruelties of the criminal justice system. Yet, as Nicole Fleetwood reveals, America’s prisons are filled with art. Despite the isolation and degradation they experience, the incarcerated are driven to assert their humanity in the face of a system that dehumanizes them.

Based on interviews with currently and formerly incarcerated artists, prison visits, and the author’s own family experiences with the penal system, Marking Time shows how the imprisoned turn ordinary objects into elaborate works of art. Working with meager supplies and in the harshest conditions—including solitary confinement—these artists find ways to resist the brutality and depravity that prisons engender. The impact of their art, Fleetwood observes, can be felt far beyond prison walls. Their bold works, many of which are being published for the first time in this volume, have opened new possibilities in American art.

As the movement to transform the country’s criminal justice system grows, art provides the imprisoned with a political voice. Their works testify to the economic and racial injustices that underpin American punishment and offer a new vision of freedom for the twenty-first century.

Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War

Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War

by Tabitha BrownBelknap Press (Jan 14, 2020)

Read Detailed Book Description

Winner of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award

Winner of the James A. Rawley Prize in the History of Race Relations

Winner of the Phillis Wheatley Book Award

Finalist for the Cundill Prize

A gripping account of the largest slave revolt in the eighteenth-century British Atlantic world, an uprising that laid bare the interconnectedness of Europe, Africa, and America, shook the foundations of empire, and reshaped ideas of race and popular belonging.

In the second half of the eighteenth century, as European imperial conflicts extended the domain of capitalist agriculture, warring African factions fed their captives to the transatlantic slave trade while masters struggled continuously to keep their restive slaves under the yoke. In this contentious atmosphere, a movement of enslaved West Africans in Jamaica (then called Coromantees) organized to throw off that yoke by violence. Their uprising—which became known as Tacky’s Revolt—featured a style of fighting increasingly familiar today: scattered militias opposing great powers, with fighters hard to distinguish from noncombatants. It was also part of a more extended borderless conflict that spread from Africa to the Americas and across the island. Even after it was put down, the insurgency rumbled throughout the British Empire at a time when slavery seemed the dependable bedrock of its dominion. That certitude would never be the same, nor would the views of black lives, which came to inspire both more fear and more sympathy than before.

Tracing the roots, routes, and reverberations of this event across disparate parts of the Atlantic world, Vincent Brown offers us a superb geopolitical thriller. Tacky’s Revolt expands our understanding of the relationship between European, African, and American history, as it speaks to our understanding of wars of terror today.

The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America

The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America

by Khalil G. MuhammadHarvard University Press (Jul 22, 2019)

Read Detailed Book Description

Winner of the John Hope Franklin Prize

A Moyers & Company Best Book of the Year

“A brilliant work that tells us how directly the past has formed us.”

—Darryl Pinckney, New York Review of Books

At the turn of the 20th century, reformers and social scientists argued that

high rates of crime and violence among white European immigrants could be

explained by poverty, discrimination and social upheaval. Improve social

conditions, they said, and immigrants would be like the native-born. But the

same argument didn't apply when it came to African Americans. Liberals and

conservatives alike accepted that high crime rates for blacks were evidence

of racial inferiority.

In his new book The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making

of Urban America, Khalil Gibran Muhammad, an assistant professor of history

at Indiana University, tells "an unsettling coming-of-age story" about the

idea of black criminality in modern America.

The conflation of crime and race takes hold in the post-Reconstruction

period, he writes, when "Southerners used crime to justify disfranchisement,

lynching and Jim Crow segregation; Northerners used it to justify municipal

neglect, joblessness, and residential segregation."

The Condemnation of Blackness, published by Harvard University Press, shows

how social scientists refashioned blackness through newly available crime

data. In the words of historian David Levering Lewis, the book "disrupts one

of the nation's most insidious, convenient and resilient explanatory loops:

whites commit crimes, but black males are criminals."

At the heart of the initial story is the 1890 census, the first to describe

the generation of African Americans born after the Civil War. Among its

findings: blacks made up 30 percent of U.S. prisoners but only 12 percent of

the overall population. Coming at a time of "race fatigue," with slavery

abolished and the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution supposedly

having extended civil rights to blacks, the data were presented as proof

that America's "Negro Problem" was intractable. The age of Jim Crow

segregation was just beginning.

"Even Northern liberals saw it as a reflection not of racism but of black

people's bad behavior. They believed that African Americans hadn't developed

'internal controls' or recognized that freedom comes with responsibility,"

Muhammad said. "This is striking because, it's at the exact moment when the

opposite argument was being made for European immigrants — that they need

to be helped, to be Americanized, and it needs to happen now." Northern

social workers set about to save the "great army of unfortunates," but left

blacks alone to "work out their own salvation."

The linking of race and crime rested heavily on the work of certain

influential scholars. Harvard professor Nathaniel Shaler wrote that blacks

"are a danger to America greater and more insuperable than any of those that

menace the other great civilized states of the world." Statistician

Frederick Hoffman's Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro,

published in 1896, "combined crime statistics with a well-crafted white

supremacist narrative to shape the reading of black criminality while trying

to minimize the appearance of doing so," Muhammad writes.

At the same time, African Americans such as the social scientist W.E.B. Du

Bois and the reformer Ida B. Wells documented racism and discrimination but

remained outside the mainstream.

The story changes as the decades pass. The Great Migration, starting around

1910, brought a half million blacks from the South to the cities of the

Northeast and Midwest. Race riots struck more than 20 cities, sometimes with

police aiding white mobs who attacked blacks. Evidence accumulated that, in

the North as in the South, American justice wasn't colorblind — and a new

generation of black and white social scientists concluded that crime

statistics were not a reliable measure of criminal activity because racism

was unaccounted for.

The book ends on the eve of World War II, but the story goes on. Muhammad

points out that "the link between race and crime is as enduring and

influential in the 21st century as it has been in the past," with blacks

accounting for nearly half of the more than two million Americans now behind

bars. He argues that numbers don't "speak for themselves," however, and that

the flaws in how race and crime data were used in the past should make us

cautious about how we use them today.

"The invisible layers of racial ideology packed into the statistics,

sociological theories, and the everyday stories we continue to tell about

crime in modern urban America are a legacy of the past," he writes. "The

choice about which narratives we attach to the data in the future, however,

is ours to make."

The Best of the Best Panini Press Cookbook: 100 Surefire Recipes for Making Panini—And Many Other Things—On Your Panini Press or Other Countertop Grill

The Best of the Best Panini Press Cookbook: 100 Surefire Recipes for Making Panini—And Many Other Things—On Your Panini Press or Other Countertop Grill

by Kathy StrahsHarvard University Press (Mar 12, 2019)

Read Detailed Book Description

Your panini press will become your most versatile friend in the kitchen with The Ultimate Panini Press Cookbook, a compendium of Kathy Strahs’s best 100 panini press recipes, beautifully illustrated with new color photos.

Who knew this simple and easy-to-use kitchen appliance could do so much?

Kathy Strahs, for one, did. Creator of the multiple-award-winning food blog Panini Happy, the web’s go-to destination for panini-press wisdom, Strahs does wonderful things with a panini press, from crafting perfect Italian-style panini to building scrumptious and creative grilled cheese sandwiches to making things you never thought you could make on a countertop grill or griddle.

Dig into these recipes to discover your panini press’s impressive range—including breakfasts, lunches, snacks, and dinners, for the weekday whirl and for relaxing times on weekends. About half the recipes in this book—a collection of the 100 best recipes from Strahs’s earlier book, The Ultimate Panini Press Cookbook—are for panini, such as a robust Cheddar, Apple, and Whole-Grain Mustard Panini or a zesty Chimichurri Steak Panini. The remaining recipes are for dishes you will be amazed to learn you can make on a countertop grill, including quesadillas, croques monsieurs, brats, burgers, salads topped with crisply grilled meats, and even grilled desserts.

This beautiful volume will inspire great cooking and fun meals, without the fuss or effort.

The Limits of Blame: Rethinking Punishment and Responsibility

The Limits of Blame: Rethinking Punishment and Responsibility

by Erin I. KellyHarvard University Press (Nov 12, 2018)

Read Detailed Book Description

Faith in the power and righteousness of retribution has taken over the American criminal justice system. Approaching punishment and responsibility from a philosophical perspective, Erin Kelly challenges the moralism behind harsh treatment of criminal offenders and calls into question our society’s commitment to mass incarceration.

The Limits of Blame takes issue with a criminal justice system that aligns legal criteria of guilt with moral criteria of blameworthiness. Many incarcerated people do not meet the criteria of blameworthiness, even when they are guilty of crimes. Kelly underscores the problems of exaggerating what criminal guilt indicates, particularly when it is tied to the illusion that we know how long and in what ways criminals should suffer. Our practice of assigning blame has gone beyond a pragmatic need for protection and a moral need to repudiate harmful acts publicly. It represents a desire for retribution that normalizes excessive punishment.

Appreciating the limits of moral blame critically undermines a commonplace rationale for long and brutal punishment practices. Kelly proposes that we abandon our culture of blame and aim at reducing serious crime rather than imposing retribution. Were we to refocus our perspective to fit the relevant moral circumstances and legal criteria, we could endorse a humane, appropriately limited, and more productive approach to criminal justice.

How the Other Half Banks: Exclusion, Exploitation, and the Threat to Democracy

How the Other Half Banks: Exclusion, Exploitation, and the Threat to Democracy

by Mehrsa BaradaranHarvard University Press (Mar 12, 2018)

Read Detailed Book Description

The United States has two separate banking systems today—one serving the well-to-do and another exploiting everyone else. How the Other Half Banks contributes to the growing conversation on American inequality by highlighting one of its prime causes: unequal credit. Mehrsa Baradaran examines how a significant portion of the population, deserted by banks, is forced to wander through a Wild West of payday lenders and check-cashing services to cover emergency expenses and pay for necessities—all thanks to deregulation that began in the 1970s and continues decades later.

"Baradaran argues persuasively that the banking industry, fattened on public subsidies (including too-big-to-fail bailouts), owes low-income families a better deal…How the Other Half Banks is well researched and clearly written…The bankers who fully understand the system are heavily invested in it. Books like this are written for the rest of us."—Nancy Folbre, New York Times Book Review "How the Other Half Banks tells an important story, one in which we have allowed the profit motives of banks to trump the public interest."

—Lisa J. Servon, American Prospect

The Origin of Others

The Origin of Others

by Toni MorrisonHarvard University Press (Sep 18, 2017)

Read Detailed Book Description

America’s foremost novelist reflects on the themes that preoccupy her work and increasingly dominate national and world politics: race, fear, borders, the mass movement of peoples, the desire for belonging. What is race and why does it matter? What motivates the human tendency to construct Others? Why does the presence of Others make us so afraid?

Drawing on her Norton Lectures, Toni Morrison takes up these and other vital questions bearing on identity in The Origin of Others. In her search for answers, the novelist considers her own memories as well as history, politics, and especially literature. Harriet Beecher Stowe, Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and Camara Laye are among the authors she examines. Readers of Morrison’s fiction will welcome her discussions of some of her most celebrated books—Beloved, Paradise, and A Mercy.

If we learn racism by example, then literature plays an important part in the history of race in America, both negatively and positively. Morrison writes about nineteenth-century literary efforts to romance slavery, contrasting them with the scientific racism of Samuel Cartwright and the banal diaries of the plantation overseer and slaveholder Thomas Thistlewood. She looks at configurations of blackness, notions of racial purity, and the ways in which literature employs skin color to reveal character or drive narrative. Expanding the scope of her concern, she also addresses globalization and the mass movement of peoples in this century. National Book Award winner Ta-Nehisi Coates provides a foreword to Morrison’s most personal work of nonfiction to date.

The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap

The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap

by Mehrsa BaradaranBelknap Press (Sep 14, 2017)

Read Detailed Book Description

"Read this book. It explains so much about the moment…Beautiful, heartbreaking work."

—Ta-Nehisi Coates

From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America

From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America

by Elizabeth HintonHarvard University Press (Sep 04, 2017)

Read Detailed Book Description

From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime requires slow and careful reading for anyone seeking to grasp the full implications of this exceedingly well-researched work…The book is vivid with detail and sharp analysis…Hinton’s book is more than an argument; it is a revelation…There are moments that will make your skin crawl…This is history, but the implications for today are striking. Readers will learn how the militarization of the police that we’ve witnessed in Ferguson and elsewhere had roots in the 1960s…A reader cannot help reckoning with the truth that the problem of police brutality and mass incarceration won’t be remedied with technology and training. Those of us who believe in the principles of democracy and justice would do well to witness, as detailed in Hinton’s pages, the shameful theft of liberty in this so-called land of the free.—Imani Perry "New York Times Book Review" (5/29/2016 12:00:00 AM)

As If: Idealization and Ideals

As If: Idealization and Ideals

by Kwame Anthony AppiahHarvard University Press (Aug 14, 2017)

Read Detailed Book Description

Idealization is a fundamental feature of human thought. We build simplified models in our scientific research and utopias in our political imaginations. Concepts like belief, desire, reason, and justice are bound up with idealizations and ideals. Life is a constant adjustment between the models we make and the realities we encounter. In idealizing, we proceed “as if” our representations were true, while knowing they are not. This is not a dangerous or distracting occupation, Kwame Anthony Appiah shows. Our best chance of understanding nature, society, and ourselves is to open our minds to a plurality of imperfect depictions that together allow us to manage and interpret our world.The philosopher Hans Vaihinger first delineated the “as if” impulse at the turn of the twentieth century, drawing on Kant, who argued that rational agency required us to act as if we were free. Appiah extends this strategy to examples across philosophy and the human and natural sciences. In a broad range of activities, we have some notion of the truth yet continue with theories that we recognize are, strictly speaking, false. From this vantage point, Appiah demonstrates that a picture one knows to be unreal can be a vehicle for accessing reality.As If explores how strategic untruth plays a critical role in far-flung areas of inquiry: decision theory, psychology, natural science, and political philosophy. A polymath who writes with mainstream clarity, Appiah defends the centrality of the imagination not just in the arts but in science, morality, and everyday life.

The Long Emancipation: The Demise of Slavery in the United States

The Long Emancipation: The Demise of Slavery in the United States

by Ira BerlinHarvard University Press (Sep 15, 2015)

Read Detailed Book Description

Perhaps no event in American history arouses more impassioned debate than the abolition of slavery. Answers to basic questions about who ended slavery, how, and why remain fiercely contested more than a century and a half after the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment. In The Long Emancipation, Ira Berlin draws upon decades of study to offer a framework for understanding slavery’s demise in the United States. Freedom was not achieved in a moment, and emancipation was not an occasion but a near-century-long process—a shifting but persistent struggle that involved thousands of men and women.

Berlin teases out the distinct characteristics of emancipation, weaving them into a larger narrative of the meaning of American freedom. The most important factor was the will to survive and the enduring resistance of enslaved black people themselves. In striving for emancipation, they were also the first to raise the crucial question of their future status. If they were no longer slaves, what would they be? African Americans provided the answer, drawing on ideals articulated in the Declaration of Independence and precepts of evangelical Christianity. Freedom was their inalienable right in a post-slavery society, for nothing seemed more natural to people of color than the idea that all Americans should be equal. African Americans were not naive about the price of their idealism. Just as slavery was an institution initiated and maintained by violence, undoing slavery also required violence. Freedom could be achieved only through generations of long and brutal struggle. Seven Modes of Uncertainty

Seven Modes of Uncertainty

by Namwali SerpellHarvard University Press (Apr 30, 2014)

Read Detailed Book Description

Literature is rife with uncertainty. Literature is good for us. These two ideas about reading literature are often taken for granted. But what is the relationship between literature’s capacity to unsettle, perplex, and bewilder us, and literature’s ethical value? To revive this question, C. Namwali Serpell proposes a return to William Empson’s groundbreaking work, Seven Types of Ambiguity (1930), which contends that literary uncertainty is crucial to ethics because it pushes us beyond the limits of our own experience.Taking as case studies experimental novels by Thomas Pynchon, Toni Morrison, Bret Easton Ellis, Ian McEwan, Elliot Perlman, Tom McCarthy, and Jonathan Safran Foer, Serpell suggests that literary uncertainty emerges from the reader’s shifting responses to structures of conflicting information. A number of these novels employ a structure of mutual exclusion, which presents opposed explanations for the same events. Some use a structure of multiplicity, which presents different perspectives regarding events or characters. The structure of repetition in other texts destabilizes the continuity of events and frustrates our ability to follow the story.To explain how these structures produce uncertainty, Serpell borrows from cognitive psychology the concept of affordance, which describes an object’s or environment’s potential uses. Moving through these narrative structures affords various ongoing modes of uncertainty, which in turn afford ethical experiences both positive and negative. At the crossroads of recent critical turns to literary form, reading practices, and ethics, Seven Modes of Uncertainty offers a new phenomenology of how we read uncertainty now.

The Craft of Ralph Ellison

The Craft of Ralph Ellison

by Robert G. O’MeallyHarvard University Press (Apr 11, 2014)

Read Detailed Book Description

Lines of Descent: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Emergence of Identity (The W. E. B. Du Bois Lectures)

Lines of Descent: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Emergence of Identity (The W. E. B. Du Bois Lectures)

by Kwame Anthony AppiahHarvard University Press (Feb 27, 2014)

Read Detailed Book Description

W. E. B. Du Bois never felt so at home as when he was a student at the University of Berlin. But Du Bois was also American to his core, scarred but not crippled by the racial humiliations of his homeland. In Lines of Descent, Kwame Anthony Appiah traces the twin lineages of Du Bois’ American experience and German apprenticeship, showing how they shaped the great African-American scholar’s ideas of race and social identity.At Harvard, Du Bois studied with such luminaries as William James and George Santayana, scholars whose contributions were largely intellectual. But arriving in Berlin in 1892, Du Bois came under the tutelage of academics who were also public men. The economist Adolf Wagner had been an advisor to Otto von Bismarck. Heinrich von Treitschke, the historian, served in the Reichstag, and the economist Gustav von Schmoller was a member of the Prussian state council. These scholars united the rigorous study of history with political activism and represented a model of real-world engagement that would strongly influence Du Bois in the years to come.With its romantic notions of human brotherhood and self-realization, German culture held a potent allure for Du Bois. Germany, he said, was the first place white people had treated him as an equal. But the prevalence of anti-Semitism allowed Du Bois no illusions that the Kaiserreich was free of racism. His challenge, says Appiah, was to take the best of German intellectual life without its parochialism—to steal the fire without getting burned.

The Ultimate Panini Press Cookbook: More Than 200 Perfect-Every-Time Recipes for Making Panini - And Lots of Other Things - On Your Panini Press or Other

The Ultimate Panini Press Cookbook: More Than 200 Perfect-Every-Time Recipes for Making Panini - And Lots of Other Things - On Your Panini Press or Other

by Kathy StrahsHarvard University Press (Sep 10, 2013)

Read Detailed Book Description

Your panini press will become your most versatile friend in the kitchen with The Ultimate Panini Press Cookbook, a compendium of Kathy Strahs’s best 100 panini press recipes, beautifully illustrated with new color photos.

Who knew this simple and easy-to-use kitchen appliance could do so much?

Kathy Strahs, for one, did. Creator of the multiple-award-winning food blog Panini Happy, the web’s go-to destination for panini-press wisdom, Strahs does wonderful things with a panini press, from crafting perfect Italian-style panini to building scrumptious and creative grilled cheese sandwiches to making things you never thought you could make on a countertop grill or griddle.

Dig into these recipes to discover your panini press’s impressive range—including breakfasts, lunches, snacks, and dinners, for the weekday whirl and for relaxing times on weekends. About half the recipes in this book—a collection of the 100 best recipes from Strahs’s earlier book, The Ultimate Panini Press Cookbook—are for panini, such as a robust Cheddar, Apple, and Whole-Grain Mustard Panini or a zesty Chimichurri Steak Panini. The remaining recipes are for dishes you will be amazed to learn you can make on a countertop grill, including quesadillas, croques monsieurs, brats, burgers, salads topped with crisply grilled meats, and even grilled desserts.

This beautiful volume will inspire great cooking and fun meals, without the fuss or effort.

Africa Speaks, America Answers: Modern Jazz in Revolutionary Times

Africa Speaks, America Answers: Modern Jazz in Revolutionary Times

by Robin D. G. KelleyHarvard University Press (Feb 27, 2012)

Read Detailed Book Description

In Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, pianist Randy Weston and bassist Ahmed Abdul-Malik celebrated with song the revolutions spreading across Africa. In Ghana and South Africa, drummer Guy Warren and vocalist Sathima Bea Benjamin fused local musical forms with the dizzying innovations of modern jazz. These four were among hundreds of musicians in the 1950s and ’60s who forged connections between jazz and Africa that definitively reshaped both their music and the world.

Each artist identified in particular ways with Africa’s struggle for liberation and made music dedicated to, or inspired by, demands for independence and self-determination. That music was the wild, boundary-breaking exultation of modern jazz. The result was an abundance of conversation, collaboration, and tension between African and African American musicians during the era of decolonization. This collective biography demonstrates how modern Africa reshaped jazz, how modern jazz helped form a new African identity, and how musical convergences and crossings altered politics and culture on both continents.

In a crucial moment when freedom electrified the African diaspora, these black artists sought one another out to create new modes of expression. Documenting individuals and places, from Lagos to Chicago, from New York to Cape Town, Robin Kelley gives us a meditation on modernity: we see innovation not as an imposition from the West but rather as indigenous, multilingual, and messy, the result of innumerable exchanges across a breadth of cultures.

Freedom Struggles: African Americans and World War I

Freedom Struggles: African Americans and World War I

by Adriane Lentz-SmithHarvard University Press (Sep 30, 2011)

Read Detailed Book Description

For many of the 200,000 black soldiers sent to Europe with the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I, encounters with French civilians and colonial African troops led them to imagine a world beyond Jim Crow. They returned home to join activists working to make that world real. In narrating the efforts of African American soldiers and activists to gain full citizenship rights as recompense for military service, Adriane Lentz-Smith illuminates how World War I mobilized a generation.Black and white soldiers clashed as much with one another as they did with external enemies. Race wars within the military and riots across the United States demonstrated the lengths to which white Americans would go to protect a carefully constructed caste system. Inspired by Woodrow Wilson’s rhetoric of self-determination but battered by the harsh realities of segregation, African Americans fought their own “war for democracy,” from the rebellions of black draftees in French and American ports to the mutiny of Army Regulars in Houston, and from the lonely stances of stubborn individuals to organized national campaigns. African Americans abroad and at home reworked notions of nation and belonging, empire and diaspora, manhood and citizenship. By war’s end, they ceased trying to earn equal rights and resolved to demand them.This beautifully written book reclaims World War I as a critical moment in the freedom struggle and places African Americans at the crossroads of social, military, and international history.

A Level Playing Field: African American Athletes and the Republic of Sports

A Level Playing Field: African American Athletes and the Republic of Sports

by Gerald L. EarlyHarvard University Press (Apr 29, 2011)

Read Detailed Book Description

As Americans, we believe there ought to be a level playing field for everyone. Even if we don’t expect to finish first, we do expect a fair start. Only in sports have African Americans actually found that elusive level ground. But at the same time, black players offer an ironic perspective on the athlete-hero, for they represent a group historically held to be without social honor.In his first new collection of sports essays since Tuxedo Junction (1989), the noted cultural critic Gerald Early investigates these contradictions as they play out in the sports world and in our deeper attitudes toward the athletes we glorify. Early addresses a half-century of heated cultural issues ranging from integration to the use of performance-enhancing drugs. Writing about Jackie Robinson and Curt Flood, he reconstructs pivotal moments in their lives and explains how the culture, politics, and economics of sport turned with them. Taking on the subtexts, racial and otherwise, of the controversy over remarks Rush Limbaugh made about quarterback Donovan McNabb, Early restores the political consequence to an event most commentators at the time approached with predictable bluster. The essays in this book circle around two perennial questions: What other, invisible contests unfold when we watch a sporting event? What desires and anxieties are encoded in our worship of (or disdain for) high-performance athletes?These essays are based on the Alain Locke lectures at Harvard University’s Du Bois Institute.

The Condemnation Of Blackness: Race, Crime, And The Making Of Modern Urban America

The Condemnation Of Blackness: Race, Crime, And The Making Of Modern Urban America

by Khalil G. MuhammadHarvard University Press (Feb 15, 2010)

Read Detailed Book Description

Lynch mobs, chain gangs, and popular views of black southern criminals that defined the Jim Crow South are well known. We know less about the role of the urban North in shaping views of race and crime in American society. Following the 1890 census, the first to measure the generation of African Americans born after slavery, crime statistics, new migration and immigration trends, and symbolic references to America as the promised land of opportunity were woven into a cautionary tale about the exceptional threat black people posed to modern urban society. Excessive arrest rates and overrepresentation in northern prisons were seen by many whites—liberals and conservatives, northerners and southerners—as indisputable proof of blacks’ inferiority. In the heyday of “separate but equal,” what else but pathology could explain black failure in the “land of opportunity”? The idea of black criminality was crucial to the making of modern urban America, as were African Americans’ own ideas about race and crime. Chronicling the emergence of deeply embedded notions of black people as a dangerous race of criminals by explicit contrast to working-class whites and European immigrants, this fascinating book reveals the influence such ideas have had on urban development and social policies.

Big Enough To Be Inconsistent: Abraham Lincoln Confronts Slavery And Race (The W. E. B. Du Bois Lectures)

Big Enough To Be Inconsistent: Abraham Lincoln Confronts Slavery And Race (The W. E. B. Du Bois Lectures)

by George M. FredricksonHarvard University Press (Feb 28, 2008)

Read Detailed Book Description

“Cruel, merciful; peace-loving, a fighter; despising Negroes and letting them fight and vote; protecting slavery and freeing slaves.” Abraham Lincoln was, W. E. B. Du Bois declared, “big enough to be inconsistent.” Big enough, indeed, for every generation to have its own Lincoln—unifier or emancipator, egalitarian or racist. In an effort to reconcile these views, and to offer a more complex and nuanced account of a figure so central to American history, this book focuses on the most controversial aspect of Lincoln’s thought and politics—his attitudes and actions regarding slavery and race. Drawing attention to the limitations of Lincoln’s judgment and policies without denying his magnitude, the book provides the most comprehensive and even-handed account available of Lincoln’s contradictory treatment of black Americans in matters of slavery in the South and basic civil rights in the North. George Fredrickson shows how Lincoln’s antislavery convictions, however genuine and strong, were held in check by an equally strong commitment to the rights of the states and the limitations of federal power. He explores how Lincoln’s beliefs about racial equality in civil rights, stirred and strengthened by the African American contribution to the northern war effort, were countered by his conservative constitutional philosophy, which left this matter to the states. The Lincoln who emerges from these pages is far more comprehensible and credible in his inconsistencies, and in the abiding beliefs and evolving principles from which they arose. Deeply principled but nonetheless flawed, all-too-human yet undeniably heroic, he is a Lincoln for all generations.

Experiments in Ethics (Flexner Lectures)

Experiments in Ethics (Flexner Lectures)

by Kwame Anthony AppiahHarvard University Press (Jan 15, 2008)

Read Detailed Book Description

In the past few decades, scientists of human nature—including experimental and cognitive psychologists, neuroscientists, evolutionary theorists, and behavioral economists—have explored the way we arrive at moral judgments. They have called into question commonplaces about character and offered troubling explanations for various moral intuitions. Research like this may help explain what, in fact, we do and feel. But can it tell us what we ought to do or feel? In Experiments in Ethics, the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah explores how the new empirical moral psychology relates to the age-old project of philosophical ethics. Some moral theorists hold that the realm of morality must be autonomous of the sciences; others maintain that science undermines the authority of moral reasons. Appiah elaborates a vision of naturalism that resists both temptations. He traces an intellectual genealogy of the burgeoning discipline of "experimental philosophy," provides a balanced, lucid account of the work being done in this controversial and increasingly influential field, and offers a fresh way of thinking about ethics in the classical tradition. Appiah urges that the relation between empirical research and morality, now so often antagonistic, should be seen in terms of dialogue, not contest. And he shows how experimental philosophy, far from being something new, is actually as old as philosophy itself. Beyond illuminating debates about the connection between psychology and ethics, intuition and theory, his book helps us to rethink the very nature of the philosophical enterprise.

In Search of Nella Larsen: A Biography of the Color Line

In Search of Nella Larsen: A Biography of the Color Line

by George HutchinsonBelknap Press (May 30, 2006)

Read Detailed Book Description

Born to a Danish seamstress and a black West Indian cook in one of the Western Hemisphere’s most infamous vice districts, Nella Larsen (1891-1964) lived her life in the shadows of America’s racial divide. She wrote about that life, was briefly celebrated in her time, then was lost to later generations—only to be rediscovered and hailed by many as the best black novelist of her generation. In his search for Nella Larsen, the "mystery woman of the Harlem Renaissance," George Hutchinson exposes the truths and half-truths surrounding this central figure of modern literary studies, as well as the complex reality they mask and mirror. His book is a cultural biography of the color line as it was lived by one person who truly embodied all of its ambiguities and complexities.

Author of a landmark study of the Harlem Renaissance, Hutchinson here produces the definitive account of a life long obscured by misinterpretations, fabrications, and omissions. He brings Larsen to life as an often tormented modernist, from the trauma of her childhood to her emergence as a star of the Harlem Renaissance. Showing the links between her experiences and her writings, Hutchinson illuminates the singularity of her achievement and shatters previous notions of her position in the modernist landscape. Revealing the suppressions and misunderstandings that accompany the effort to separate black from white, his book addresses the vast consequences for all Americans of color-line culture’s fundamental rule: race trumps family.

Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves (Revised)

Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves (Revised)

by Ira BerlinBelknap Press (Sep 30, 2004)

Read Detailed Book Description

Ira Berlin traces the history of African-American slavery in the United States from its beginnings in the seventeenth century to its fiery demise nearly three hundred years later.

Most Americans, black and white, have a singular vision of slavery, one fixed in the mid-nineteenth century when most American slaves grew cotton, resided in the deep South, and subscribed to Christianity. Here, however, Berlin offers a dynamic vision, a major reinterpretation in which slaves and their owners continually renegotiated the terms of captivity. Slavery was thus made and remade by successive generations of Africans and African Americans who lived through settlement and adaptation, plantation life, economic transformations, revolution, forced migration, war, and ultimately, emancipation. Berlin’s understanding of the processes that continually transformed the lives of slaves makes Generations of Captivity essential reading for anyone interested in the evolution of antebellum America. Connecting the "Charter Generation" to the development of Atlantic society in the seventeenth century, the "Plantation Generation" to the reconstruction of colonial society in the eighteenth century, the "Revolutionary Generation" to the Age of Revolutions, and the "Migration Generation" to American expansionism in the nineteenth century, Berlin integrates the history of slavery into the larger story of American life. He demonstrates how enslaved black people, by adapting to changing circumstances, prepared for the moment when they could seize liberty and declare themselves the "Freedom Generation." This epic story, told by a master historian, provides a rich understanding of the experience of African-American slaves, an experience that continues to mobilize American thought and passions today. Stagolee Shot Billy

Stagolee Shot Billy

by Cecil BrownHarvard University Press (May 22, 2003)

Read Detailed Book Description

Although his story has been told countless times—by performers from Ma Rainey, Cab Calloway, and the Isley Brothers to Ike and Tina Turner, James Brown, and Taj Mahal—no one seems to know who Stagolee really is. Stack Lee? Stagger Lee? He has gone by all these names in the ballad that has kept his exploits before us for over a century. Delving into a subculture of St. Louis known as "Deep Morgan," Cecil Brown emerges with the facts behind the legend to unfold the mystery of Stack Lee and the incident that led to murder in 1895. How the legend grew is a story in itself, and Brown tracks it through variants of the song "Stack Lee"—from early ragtime versions of the ’20s, to Mississippi John Hurt’s rendition in the ’30s, to John Lomax’s 1940s prison versions, to interpretations by Lloyd Price, James Brown, and Wilson Pickett, right up to the hip-hop renderings of the ’90s. Drawing upon the works of James Baldwin, Richard Wright, and Ralph Ellison, Brown describes the powerful influence of a legend bigger than literature, one whose transformation reflects changing views of black musical forms, and African Americans’ altered attitudes toward black male identity, gender, and police brutality. This book takes you to the heart of America, into the soul and circumstances of a legend that has conveyed a painful and elusive truth about our culture.

The Miner’s Canary: Enlisting Race, Resisting Power, Transforming Democracy

The Miner’s Canary: Enlisting Race, Resisting Power, Transforming Democracy

by Lani GuinierHarvard University Press (Apr 21, 2003)

Read Detailed Book Description

Like the canaries that alerted miners to a poisonous atmosphere, issues of race point to underlying problems in society that ultimately affect everyone, not just minorities. Addressing these issues is essential. Ignoring racial differences—race blindness—has failed. Focusing on individual achievement has diverted us from tackling pervasive inequalities. Now, in a powerful and challenging book, Lani Guinier and Gerald Torres propose a radical new way to confront race in the twenty-first century.

Given the complex relationship between race and power in America, engaging race means engaging standard winner-take-all hierarchies of power as well. Terming their concept political race, Guinier and Torres call for the building of grass-roots, cross-racial coalitions to remake those structures of power by fostering public participation in politics and reforming the process of democracy. Their illuminating and moving stories of political race in action include the coalition of Hispanic and black leaders who devised the Texas Ten Percent Plan to establish equitable state college admissions criteria, and the struggle of black workers in North Carolina for fair working conditions that drew on the strength and won the support of the entire local community.

The aim of political race is not merely to remedy racial injustices, but to create truly participatory democracy, where people of all races feel empowered to effect changes that will improve conditions for everyone. In a book that is ultimately not only aspirational but inspirational, Guinier and Torres envision a social justice movement that could transform the nature of democracy in America.

Stories of Freedom in Black New York

Stories of Freedom in Black New York

by Shane WhiteHarvard University Press (Nov 29, 2002)

Read Detailed Book Description

Through exhaustive research, White imaginatively re-creates the experience of black New Yorkers as they moved from slavery to freedom. He recovers the raucous world of the street, the elegance of the city’s African-American balls, and the grubbiness of the Police Office. This book offers a unique understanding of emancipation’s impact on everyday life, and on the many forms freedom can take.

![Click for more detail about The Harvard Guide to African-American History [With CD-ROM] by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham](https://aalbc.com/bookcovers/9780674002760.jpg) The Harvard Guide to African-American History [With CD-ROM]

The Harvard Guide to African-American History [With CD-ROM]

by Evelyn Brooks HigginbothamHarvard University Press (Jun 25, 2001)

Read Detailed Book Description

This landmark guide covers research into every aspect of African-American life and work, offering a compendium of information and interpretation about almost 400 years of African-Americans’ experiences as an ethnic group and as Americans.

The first part of the Guide contains 12 essays on historical research aids, from traditional archival and reference materials to the Internet. The second and largest part presents comprehensive and chronological bibliographies, prepared by John Thornton, Peter H. Wood, Gary B. Nash, Stephanie Shaw, Richard J. M. Blackett, Eric Foner, Leon F. Litwack, Joe W. Trotter, Jeffrey Conrad Stewart, Nancy L. Grant, Darlene Clark Hine, Clayborne Carson, John H. Bracey, Adam Biggs, and Corey Walker. The third part contains listings of resources on the special subjects of women, prepared by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham; geographical areas; and autobiography and biography, prepared by Randall K. Burkett, Leon F. Litwack, and Richard Newman. A companion CD-ROM packaged with the book makes more than 15,000 bibliography entries available for computer searching. Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Revised)

Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Revised)

by Ira BerlinBelknap Press (Mar 01, 2000)

Read Detailed Book Description

Today most Americans, black and white, identify slavery with cotton, the deep South, and the African-American church. But at the beginning of the nineteenth century, after almost two hundred years of African-American life in mainland North America, few slaves grew cotton, lived in the deep South, or embraced Christianity. Many Thousands Gone traces the evolution of black society from the first arrivals in the early seventeenth century through the Revolution. In telling their story, Ira Berlin, a leading historian of southern and African-American life, reintegrates slaves into the history of the American working class and into the tapestry of our nation.

Laboring as field hands on tobacco and rice plantations, as skilled artisans in port cities, or soldiers along the frontier, generation after generation of African Americans struggled to create a world of their own in circumstances not of their own making. In a panoramic view that stretches from the North to the Chesapeake Bay and Carolina lowcountry to the Mississippi Valley, Many Thousands Gone reveals the diverse forms that slavery and freedom assumed before cotton was king. We witness the transformation that occurred as the first generations of creole slaves—who worked alongside their owners, free blacks, and indentured whites—gave way to the plantation generations, whose back-breaking labor was the sole engine of their society and whose physical and linguistic isolation sustained African traditions on American soil.

As the nature of the slaves’ labor changed with place and time, so did the relationship between slave and master, and between slave and society. In this fresh and vivid interpretation, Berlin demonstrates that the meaning of slavery and of race itself was continually renegotiated and redefined, as the nation lurched toward political and economic independence and grappled with the Enlightenment ideals that had inspired its birth.

Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880-1920 (Revised)

Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880-1920 (Revised)

by Evelyn Brooks HigginbothamHarvard University Press (Mar 15, 1994)

Read Detailed Book Description

What Du Bois noted has gone largely unstudied until now. In this book, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham gives us our first full account of the crucial role of black women in making the church a powerful institution for social and political change in the black community. Between 1880 and 1920, the black church served as the most effective vehicle by which men and women alike, pushed down by racism and poverty, regrouped and rallied against emotional and physical defeat. Focusing on the National Baptist Convention, the largest religious movement among black Americans, Higginbotham shows us how women were largely responsible for making the church a force for self-help in the black community. In her account, we see how the efforts of women enabled the church to build schools, provide food and clothing to the poor, and offer a host of social welfare services. And we observe the challenges of black women to patriarchal theology. Class, race, and gender dynamics continually interact in Higginbotham’s nuanced history. She depicts the cooperation, tension, and negotiation that characterized the relationship between men and women church leaders as well as the interaction of southern black and northern white women’s groups.

Higginbotham’s history is at once tough-minded and engaging. It portrays the lives of individuals within this movement as lucidly as it delineates feminist thinking and racial politics. She addresses the role of black Baptist women in contesting racism and sexism through a "politics of respectability" and in demanding civil rights, voting rights, equal employment, and educational opportunities.

Righteous Discontent finally assigns women their rightful place in the story of political and social activism in the black church. It is central to an understanding of African American social and cultural life and a critical chapter in the history of religion in America.

Liberating Voices: Oral Tradition In African American Literature

Liberating Voices: Oral Tradition In African American Literature

by Gayl JonesHarvard University Press (May 01, 1991)

Read Detailed Book Description

The powerful novelist here turns penetrating critic, giving us—in lively style—both trenchant literary analysis and fresh insight on the art of writing. “When African American writers began to trust the literary possibilities of their own verbal and musical creations,” writes Gayl Jones, they began to transform the European and European American models, and to gain greater artistic sovereignty.” The vitality of African American literature derives from its incorporation of traditional oral forms: folktales, riddles, idiom, jazz rhythms, spirituals, and blues. Jones traces the development of this literature as African American writers, celebrating their oral heritage, developed distinctive literary forms. The twentieth century saw a new confidence and deliberateness in African American work: the move from surface use of dialect to articulation of a genuine black voice; the move from blacks portrayed for a white audience to characterization relieved of the need to justify. Innovative writing—such as Charles Waddell Chesnutt’s depiction of black folk culture, Langston Hughes’s poetic use of blues, and Amiri Baraka’s recreation of the short story as a jazz piece—redefined Western literary tradition. For Jones, literary technique is never far removed from its social and political implications. She documents how literary form is inherently and intensely national, and shows how the European monopoly on acceptable forms for literary art stifled American writers both black and white. Jones is especially eloquent in describing the dilemma of the African American writers: to write from their roots yet retain a universal voice; to merge the power and fluidity of oral tradition with the structure needed for written presentation. With this work Gayl Jones has added a new dimension to African American literary history.

Families in Peril: An Agenda for Social Change (Revised)

Families in Peril: An Agenda for Social Change (Revised)

by Marian Wright EdelmanHarvard University Press (Mar 01, 1989)

Read Detailed Book Description

Too many American families—unstable, broken, often poor—are in serious peril, and both the reality of the situation and the myths obscuring that reality call for attention and swift action. In this most incisive analysis of the parlous state of the family today, Marian Wright Edelman, President of the Children's Defense Fund, charts what is happening, exposes myths, and sets a bold agenda to strengthen families and protect children. In brilliant strokes and with abundant detail, Edelman describes family conditions over a generation—the rising curve of teenage pregnancy, the overwhelming joblessness of young blacks, the trend toward single-parent households, the increase in hungry and neglected children.

Dispelling common assumptions about these bleak phenomena, she shows that the birth rate for black unmarried women is stabilizing while that for unmarried whites continues to rise, that Aid to Dependent Children does not cause teenage pregnancy or births, and that the child poverty rate has increased two-thirds for whites in recent years, as opposed to one-sixth for black children. Overall, whites are losing ground faster than blacks. Speaking for a growing number of social commentators, she finds the key to explain the rising proportion of births to single black mothers: a lost generation of fathers—young black males unable to marry and support a family, jobless from lack of education and training.

What can be done? Edelman links the family and child poverty crisis to the fragile and ephemeral commitment of government to assist the needy. She suggests establishing a partnership between government, the private sector, and the black community to ensure children food, clothing, housing, medical care, and education. “Preventive investment strategies”—providing health, nutrition, and child care, raising the minimum wage, preventing teenage pregnancies, and opening up educational and employment opportunities for heads of families—will benefit us all. A passionate call to act now, to give real meaning to traditional American instincts for decency, this book is essential reading for everyone committed to preserving the nation's future.

Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market

Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market

by Walter JohnsonHarvard University Press (Jun 21, 1905)

Read Detailed Book Description

Soul by Soul tells the story of slavery in antebellum America by moving away from the cotton plantations and into the slave market itself, the heart of the domestic slave trade. Taking us inside the New Orleans slave market, the largest in the nation, where 100,000 men, women, and children were packaged, priced, and sold, Walter Johnson transforms the statistics of this chilling trade into the human drama of traders, buyers, and slaves, negotiating sales that would alter the life of each. What emerges is not only the brutal economics of trading but the vast and surprising interdependencies among the actors involved. Using recently discovered court records, slaveholders’ letters, nineteenth-century narratives of former slaves, and the financial documentation of the trade itself, Johnson reveals the tenuous shifts of power that occurred in the market’s slave coffles and showrooms. Traders packaged their slaves by “feeding them up,” dressing them well, and oiling their bodies, but they ultimately relied on the slaves to play their part as valuable commodities. Slave buyers stripped the slaves and questioned their pasts, seeking more honest answers than they could get from the traders. In turn, these examinations provided information that the slaves could utilize, sometimes even shaping a sale to their own advantage. Johnson depicts the subtle interrelation of capitalism, paternalism, class consciousness, racism, and resistance in the slave market, to help us understand the centrality of the “peculiar institution“ in the lives of slaves and slaveholders alike. His pioneering history is in no small measure the story of antebellum slavery.