Interview with Production Designer Wynn Thomas

by Booker T. Mattison

Production designer Wynn Thomas started working in theatre as a teenager growing up in Philadelphia. Upon graduation from Boston University, Thomas went to New York where he was a production designer for the Public Theatre and the Negro Ensemble Company before transitioning into film production. Thomas apprenticed under production designer Patrizia von Brandenstein (Academy Award winner for “Amadeus,” 1984) before starting a longtime collaboration with director Spike Lee.

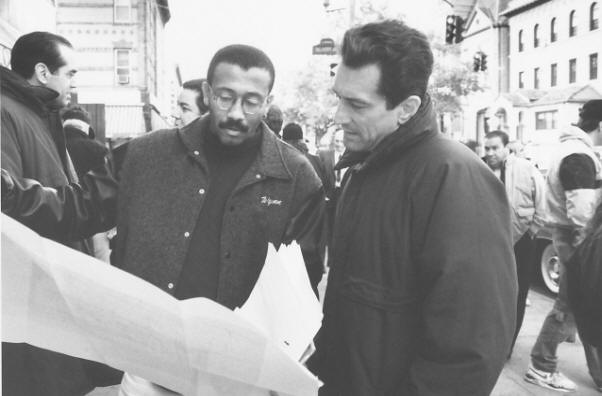

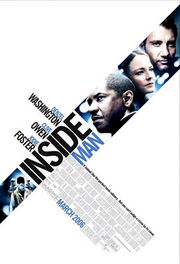

Thomas and Lee have worked together for over 20 years, on projects including “She’s Gotta Have It” (1986), “Do the Right Thing” (1989), “Mo’ Better Blues” (1990), “Malcolm X” (1992) and “Inside Man” (2006). Other credits include Robert De Niro’s directorial debut “A Bronx Tale” (1993), “To Wong Foo Thanks for Everything, Julie Newmar” (1995), Tim Burton’s “Mars Attacks!” (1996), “Wag the Dog” (1997), “Analyze This” (1999), Ron Howard’s “A Beautiful Mind” (2001) and “Cinderella Man” (2005), “Get Smart” (2008), “All Good Things” (2010) and the upcoming “The Odd Life of Timothy Green,” currently in post-production.

Wynn Thomas’ interview was conducted by filmmaker and author Booker T. Mattison (Snitch, Unsigned Hype, “The Gilded Six Bits”), exclusively for AALBC.com in the fall of 2011.

BTM: Most of the people who visit aalbc.com are readers and authors who know very little about how a movie is made (I didn’t know what a production designer was until I went to film school). Describe what a production designer does and what a production designer is responsible for.

WT: When I explain to regular people what I do, I generally say that the production designer is responsible for everything that you see before the camera. The production designer takes the words of the writer and turns them into concrete images. Nobody else in the film process does this. The director doesn’t do it. The cinematographer doesn’t do it. It is the responsibility of the production designer to take the writers words and turn them into real images.

I work closely with the director to establish the visual concept for the film. After that concept is established the production designer sets the style and visual structure for the film, and physically realizes that structure by designing the sets, choosing the locations, supervising the props, and coordinating with the costume designer so that everything in the film works together within a particular setting.

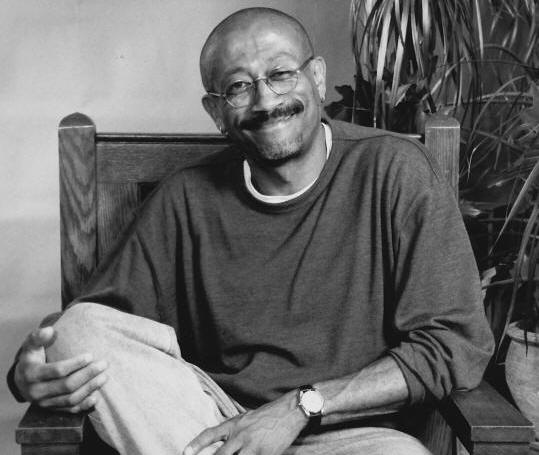

Wynn Thomas with Robert De Niro on the set of “A Bronx Tale” (Note: Chazz Palminteri)

BTM: At what point in your life did you determine that you wanted to be a production designer?

WT: My early beginnings were in the theatre, and I developed a passion for theatre as a teenager. I saw the Tennessee Williams film “Summer of Smoke” when I was 13. It starred the great Geraldine Page. I was so blown away by the film that I literally went to the library the next day and got as many Tennessee Williams plays as I could get my hands on. That movie made me realize that art and storytelling could change lives.

Soon after, I made my way down to the local theatre company in Philadelphia called the Society Hill Playhouse. I was 14 at the time and could not begin working but I had encouraged my sister, who thought she wanted to be an actress, to audition for that company. She auditioned and got in for a full season of plays. I tagged along and ended up working at the theatre from the age of 15 to 18. I acted in shows, stage-managed plays, hung lights and ran the box office. The couple that ran the theatre sort of adopted me so I spent my teenage years at the Society Hill Playhouse almost every day - working.

The interesting thing about the company was that they weren’t doing Neil Simon or other commercial plays. They were doing the work of obscure European playwrights like Günter Grass, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Jean Genet and Bertolt Brecht.

The interesting thing about the company was that they weren’t doing Neil Simon or other commercial plays. They were doing the work of obscure European playwrights like Günter Grass, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Jean Genet and Bertolt Brecht.

I was studying art in a magnet program at my high school so I was already drawing and painting. Being at the Society Hill Playhouse gave me the opportunity to combine my love of art with my love of theatre. When the time came for me to make the decision about what I wanted to study in college I decided that I wanted to become a set designer in the theatre.

I went to Boston University and got a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Theatre Design. Movies were not even on my radar in those early years. I was strictly a theatre geek and really only wanted to design for the theatre. My years at Boston University were wonderful. I went in knowing nothing and came out with enough skill and knowledge to get a job.

BTM: Early in your career you worked at The New York Public Theatre with the renowned Joseph Papp. What was it like to work with a theatre legend at such a young age?

WT: I did two really terrific plays at the New York Public Theatre. One of them was a play called Remembrance [1979]. And I have to say that when I think back on that show, it is with a great deal of regret because I was young and very stupid. I didn’t appreciate the fact that I was doing a play written by Derek Walcott and that starred Earle Hyman and Roscoe Lee Browne. I regret that I didn’t spend more time just looking at the process with these incredible men. Part of the arrogance of youth is that often your world is centered around yourself. So I wasn’t aware that I was working with legends.

The Joseph Papp Public Theatre

My second show at the Public was a play called Jonin’ that was written by Gerard Brown. It was set in a college dorm, and there were a lot of actors in that show that went on to fame and fortune in television, Eriq La Salle being one of them. It was a fantastic play to work on, and we all thought that we were going to change the world. Some of us did. Many went on to bigger and better things.

As for my memory of Joseph Papp… back then I didn’t like the guy very much because I felt that he got in the way of the creative process. Mind you, I was the arrogant twenty-something that I just described. But in retrospect I realize that Joseph Papp’s interference helped to shape and mold the play into better theatre.

During those years the Public Theatre was at the peak of their success and visibility so on any given day you could walk down the halls and see Meryl Streep, Christopher Walken, Sam Waterson and many other actors. It was an exciting time and I was thrilled to be there.

BTM: You also worked at the Negro Ensemble Company. Who were some of the actors that you worked with during your tenure there, and did any of you think that you would achieve the level of success that you have?

Classic Plays from the Negro Ensemble Company

Click to order via Amazon

"Includes the full text of ten plays, including A Soldier’s Play, Home, and The River Niger. This book is a must."

—Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis

WT: In those days the Negro Ensemble Company was located on St. Mark’s Place and Second Avenue in the East Village. And it was a true ensemble company made up of actors and technicians who were all working together to put together a season of plays. Everyone was being paid the same amount of money, which I believe was $225 a week. My first year at the Negro Ensemble Company there was an unemployed young actor there who supported his family by working as a stage carpenter. That actor was Samuel L. Jackson. So when I see Sam now I remember him as the stage carpenter who built all of my sets, not the big star that he has since become.

Some other fantastic theatre actors who were there at that time were Barbara Montgomery, Francis Foster, Graham Brown, Michele Shay, Ethel Ayler and Arthur French. It was a great time, and the people there were just happy to be working in the theatre. Movies were still not on my radar. My goal was to be a successful theatre designer which, I might add, was very hard because as an African-American I had few choices. I was known as the guy who did all the black plays, so I was pigeon-holed. I wasn’t given the opportunity to do Shakespeare and Molière, which frustrated me because in my teenage years that was the work that I was doing.

The other issue was that when you came to New York you ran up against the [theatre] guilds and the “NYU mafia,” both of which dominated the off-Broadway scene. And not just NYU, but Yale also. Both schools supplied a lot of talented designers that flooded New York City when they graduated. That was true then and is still true now. So it was very difficult for someone like me, who went to Boston University, to break into that world. I became extremely frustrated because after a few years working in theatre I felt that I wasn’t getting the design opportunities I deserved. I was a very practical person so I decided that I had to do something else in order to survive and pay rent. That’s when I said, “Well let me try movies.”

In order to work in the film business in New York City you have to be part of United Scenic Artist local 829, and I had been a member of that union for many years. Membership in local 829 enabled you to work in theatre, film and television.

An interesting sidebar is that when I passed the union exam I was the first black set designer to pass in 25 years. The African-American designer who preceded me was a set designer named Edward Burbridge who had a fantastic career.

Over a period of two years I interviewed with every major production designer in New York City and none of them hired me. It was a classic Catch-22: “We like your theatre design work, but you have no experience in film.”

I’ll give you the brief version of how I got my first break [in film]. A famous production designer named Richard Sylbert was in town designing the film “The Cotton Club.” Dick was one of the best production designers of the late twentieth century — and he had two Academy Awards to show for it. He held a [master] class and the members of local 829 were invited to come meet him. Essentially we were invited to “kiss the ring” of the great Dick Sylbert.

So I was in a room filled with sixty other union members and I was the lone black face in the audience. The next day I called “The Cotton Club” office and asked to speak with him. The person who answered the phone asked me if I knew him. I said, “Yes I know him.” That wasn’t entirely true, but I figured since I had just seen him the previous night at the meeting I’d say that I knew him. So Dick gets on the phone and I said, “Mr. Sylbert my name is Wynn Thomas. I was the black guy in the audience last night, did you see me?” He laughed and said, “Yes, I did.” I said, “Look, I have a proposition for you. I’ve been trying to work my way into the movie business. My background is in the theatre so no one has been willing to give me an opportunity. I would love to come in and show you my portfolio. If you like my work I will volunteer for you.” He immediately told me that he wasn’t hiring anyone, but said that he would be happy to take a look at my work. So I went in on a Thursday and showed him my portfolio. He reiterated that he wasn’t hiring anyone, but told me that I could come in and work for free. I did, and the following Monday turned out to be an interesting day.

“The Cotton Club” set was already being built. Dick took me on a tour of the set, and gave me a master design class my first morning there. I spent the rest of the morning doing research for him. Several times I was asked to leave his office (I don’t know why, but for some reason I was working out of his office). So I would be asked to leave the office anytime an important conversation had to occur. There was one conversation where I wasn’t asked to leave. During that discussion it was determined that the production needed someone to make models for all the sets for the director Francis Ford Coppola when he returned from Japan in a couple of weeks. Dick asked me if I wanted to do them and I said, “Sure!” The point of the story is that I had worked for free for all of four hours before I was hired to make models for multiple Academy Award winning director Francis Ford Coppola. Initially I was hired for two weeks, but that two weeks turned into six months. And that is how I got my first film job.

Once I was on “The Cotton Club” set I called all the production designers that I had previously interviewed with and told them that I was working on that film. When “The Cotton Club” was coming to an end I found out that Patrizia von Brandenstein was about to design a movie called “Beat Street” and needed help on that movie. After “The Cotton Club” wrapped I went directly into the art department on “Beat Street.”

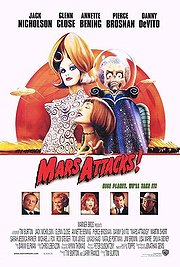

While I was working on “Beat Street” the director Stan Lathan was looking for an assistant to fetch coffee for him. One of the people who interviewed for the position was a young, talented filmmaker looking for work. That young filmmaker was Spike Lee. Spike walked into the art department and said “Wow, I didn’t know there were black people working in art direction,” and I said, “Yeah, there is me.”

By the way, Spike did not get the job as the assistant to the director, but we met and stayed in touch. Then a group of us began to hang out together. That group included me, Spike, Samuel L. Jackson and Larry Fishburne. Even in those early days when he wasn’t working Spike was formulating his [film] family. Fortunately I was one of the people who became a part of his film family early on.

The interesting thing about my early days in the movie business is that because I was in the right place at the right time my film career exploded. Once I got my first job I didn’t stop working for many, many years.

BTM: In addition to designing movies for Spike Lee (“Inside Man” and 9 other films including “Malcolm X” and “Do the Right Thing”), you have also designed films for Ron Howard (“A Beautiful Mind” and “Cinderella Man”), Robert DeNiro (“A Bronx Tale”), Tim Burton (“Mars Attacks”) and Peter Segal (“Get Smart”), among others. How is your work and style affected by the personalities of the directors you work with?

BTM: In addition to designing movies for Spike Lee (“Inside Man” and 9 other films including “Malcolm X” and “Do the Right Thing”), you have also designed films for Ron Howard (“A Beautiful Mind” and “Cinderella Man”), Robert DeNiro (“A Bronx Tale”), Tim Burton (“Mars Attacks”) and Peter Segal (“Get Smart”), among others. How is your work and style affected by the personalities of the directors you work with?

WT: Each one of the men you mentioned are very different, and part of my responsibility as a production designer is to figure out the best way to communicate with each director that I work with.

My relationship with Spike has been great from the very beginning. Spike is a director who trusts his talent so he gives you the freedom to read the script and interpret what you see in the material. Spike, as a writer/director, really puts his heart and soul into the writing of the screenplay. It has always been a pleasure working for him and, unlike some of the other directors I have worked for, Spike and I share a similar sensibility and aesthetic. I can’t put it into words, but there is something organic and natural that happens between us. We don’t need to explain things to each other because there is an innate understanding about how to approach the work. That is one of the great joys of working with him.

John Turturro, Barry Alexander Brown, Jon Kilik, Joie Lee, Spike, Monty Ross Wynn Thomas

During Gotham Awards for Spike Lee’s Film Do The Right Thing

I have done a couple of movies with Ron Howard and they were both great experiences. Ron is a strong story teller who is very receptive to the collaborative process. He has an appreciation for trying to articulate the conceptual approach to a movie. Once he has an understanding of the approach that I want to take he really gives me the freedom to go ahead and execute my ideas.

Robert De Niro was the complete opposite of Ron Howard. De Niro as a director and as an actor is methodical and approaches the material from a realistic point of view. He is not interested in abstraction. In “A Bronx Tale” he wanted to make sure that we were getting all the details correct from a realistic point of view, as opposed to a more conceptual viewpoint. When you work with De Niro and you are designing a mob hang out he is going to make sure that you see a real mob hang out. It was great meeting real mobsters and talking to them about their social clubs and the places where they hang out. I took the details from those conversations and put them up on the screen.

Robert De Niro was the complete opposite of Ron Howard. De Niro as a director and as an actor is methodical and approaches the material from a realistic point of view. He is not interested in abstraction. In “A Bronx Tale” he wanted to make sure that we were getting all the details correct from a realistic point of view, as opposed to a more conceptual viewpoint. When you work with De Niro and you are designing a mob hang out he is going to make sure that you see a real mob hang out. It was great meeting real mobsters and talking to them about their social clubs and the places where they hang out. I took the details from those conversations and put them up on the screen.

Chazz Palminteri, who wrote the screenplay for “A Bronx Tale” based on the play he wrote, was actively involved in the production of the film. He opened up his family photo albums for me to see and I used what I saw to help design the film.

I had the great honor of working with Tim Burton on “Mars Attacks.” It was very interesting working with Tim because you think that he is going to be heavily involved in designing the film since all of his movies are so visual. But what Tim will do is come in, have a discussion about the basic framework of the movie and then go away. Because Tim is a painter and an artist he understands that another artist, another painter, needs the time to develop the work. He gives you the freedom to go out and find the elements that you are going to use to design the movie. Then he comes in and takes a look at all of your designs, your sketches, your models, and then he’ll tweak them. All of a sudden it looks like a Tim Burton film.

Peter Segal, who helmed “Get Smart,” is a director that I truly love, and who is a fantastic man with a strong visual sense. What’s most important to him is that every aspect of the story is working together. He put a great deal of trust in me, and essentially stepped away from the process while I worked. Once I designed the film he came back and collaborated with me on my choices.

Wynn Thomas on set of Cinderella Man

BTM: The next question has two parts. First, walk us through your process of designing a film and then talk about the collaboration required to come up with the “look” of the film.

WT: The first thing I do is read the script for story alone. Then I go back and read the script for details. On my second reading I try to determine what the basic action of the script is. I ask myself a series of questions: “What time period is the movie taking place? Who are the characters, and what are their primary motivations? How do they live? How much money do they make? What emotional response do I want the audience to feel when they are watching the movie? What emotional response do I want the actors to have when they walk onto the set? What do the characters do for a living? What is their current emotional state, and can we see that emotional state reflected in their living environments?”

I take particular note of the primary action sequences. It is while I’m reading the script that I begin my research. My research leads me to ideas that confirm the thoughts and impressions that I get from the story. Research is invaluable because it provides me with visual pictures to draw my ideas from.

I take particular note of the primary action sequences. It is while I’m reading the script that I begin my research. My research leads me to ideas that confirm the thoughts and impressions that I get from the story. Research is invaluable because it provides me with visual pictures to draw my ideas from.

I make a research folder for each set that I will design. I find pictures, photographs, fabric, images of people, places or things, and I put this collection into the folder so that each set has its own visual material that will shape my ideas when I start to design.

After I have read the script several times I meet with the director to establish the themes and concepts of the movie. In this first meeting I find out what sequences are important to the director because my job is to help the director express what he wants in visual terms. Most directors will have one or two ideas of how they want the movie to look, but often they need help from the production designer to determine what the overall look of the movie will be. We sit down with all the research folders that I gathered, and I share the images that represent my interpretation of the tone, style and colors in the film. This gets the conversation going and usually helps the director identify potential choices that we can make.

Next I’ll sit with the cinematographer and go over what I have shown the director. Usually, the cinematographer has collected their own images that show the tone they are trying to achieve. For example, I recently finished the Disney movie “The Odd life of Timothy Green.” John Toll, a two-time Academy Award winner, was the cinematographer. The movie takes place in Middle-America and has a fairy tale feeling to it. Interestingly, both of us were attracted to the artwork of Edward Hopper. When we had our first meeting we brought in some of the same Edward Hopper paintings.

Then I go back to the script and rewrite it in visual terms. I do that by establishing specific visual concepts. Part of formulating a concept is to make up a past about the characters to support my visual choices. What I’m trying to do is give the movie a subtextual world to function in. The key word here is subtext. We should learn something about the characters and their world by seeing visual details in the settings that illuminate who they are. These concepts provide the visual metaphors that determine the visual style of the film. Once I have come up with a conceptual approach it is my job to clearly express that approach to everyone working on the film.

For example, in “Mo’ Better Blues,” which was a jazz-themed film that I made with Spike Lee many years ago, the important visual elements in that movie were: I wanted to treat the film as if it were a jazz musical, and I didn’t want the film to take place in a traditional jazz club. I wanted the set to be a jazz night club.

For example, in “Mo’ Better Blues,” which was a jazz-themed film that I made with Spike Lee many years ago, the important visual elements in that movie were: I wanted to treat the film as if it were a jazz musical, and I didn’t want the film to take place in a traditional jazz club. I wanted the set to be a jazz night club.

When I read the script it felt very much like a 1950s Hollywood musical. So that’s how I approached all the settings. When you look at the night club scenes they seem to take place in a club from another era. By treating the whole film as if it was in another time period, particularly the 1950s, it affected the choices that everyone else made. If you look at the costuming in that film for example, it looks as if the actors are clothed in costumes from the 1950s and 1960s. So that entire visual and conceptual approach effected every single decision that was made on that film. The production designer sets the framework or boundaries for everyone who is working on the film to create within.

Once everyone has signed off on the conceptual part of the design process, two things occur at the same time. I start designing all the sets that are going to be built, which means that I do a whole series of floor plans and elevations. Elevations are what we call the architectural drawings that show all the details of how the sets will look. Sometimes, if I have the time on the job, I will actually sit down and do a sketch of each set. So that’s what’s happening at my drawing board on a daily basis.

Then I begin to scout locations. Most people think that the director is out scouting locations but that isn’t true. It is actually the job of the production designer to go out and find all the locations. So at this point on the job the locations department is actually part of the art department. The location scouts and location managers are working for the production designer to find the locations.

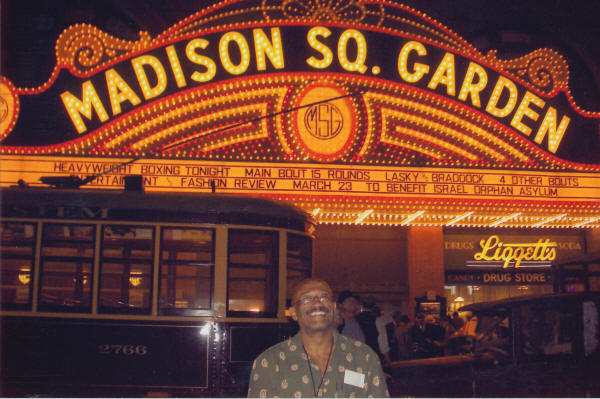

Wynn Thomas in Eygpt during the filming of Malcom X in 1992

Once I have made two or three choices about the locations, I take those folders to the director and we’ll narrow my selections further. Then we go out and begin the scouting process with the director and the producer.

That’s when my set decorator comes into the process, my closest collaborator on the film. The job of the set decorator is to work with me to establish a character through the selection of furniture choices, paintings, lamps, etc. — all of the physical things that help define who a character is in a film. Because the set decorator is my key collaborator for the big visual choices, we spend a significant amount of time exchanging ideas about what each set should say about the characters.

Shortly after the set decorator comes on board the prop guy joins the party and we have conversations about the details of what the props should be. If there are specialty props we go ahead and get those designed. Then I do an overview of all the props before the prop manager shows them to the director.

Once I have established the overall flow of the film I will put together a color reference book with all of the colors and textures that I will use for each set. So if I’m designing a room that has color paint as well as wall paper I will put all of those color references on a single sheet of paper. The color reference book goes out to the cinematographer and the costume designer so that they can see how I am using color throughout the entire film.

As the sets are being built I’m having more technical conversations with the cinematographer about how sequences will be staged and how the sets will be lit. Then my team can place lighting to help light the set. The costume designer and I will discuss how the art direction of the film and the scenery can be reflected in the costuming of the characters. I also make sure that the color palette that I have chosen works together with the costume designer’s choices so that there are no glaring mismatches in the film.

BTM: Who are some of the African-American directors whose work you admire?

WT: I like the work of the Hughes Brothers, Ernest Dickerson, Paris Barclay, and I am very excited about the work of Dee Rees who directed “Pariah.” It’s pretty difficult out there for African-American directors because there are very few opportunities, and as a result most people do not get a chance to develop a body of work. That’s a tragedy because in order to become good at what you do in this business you have to do it on a consistent basis. Too many African-American directors do not get the opportunity to work regularly.

BTM: How would you respond to the “so-called” controversy between Spike Lee and Tyler Perry? (I say “so-called” because I believe the “controversy” has largely been fueled by the entertainment media).

WT: The situation between Spike and Tyler, I think, is a clash of the titans. To me, the argument is not worthy of either man because it is an example of the type of controversy that divides our community and keeps us fighting amongst ourselves. Unfortunately it works, and it creates a lot of discord and unhappiness. The real tragedy is that these are two fantastic filmmakers who are working in different genres so they shouldn’t be criticizing each other. You don’t find Spielberg criticizing Todd Phillips. You don’t find Martin Scorsese criticizing the Farrelly brothers. This conflict goes back to Greek times. It is the classic “high” art verses “low” art conundrum. The plays of Plautus were more popular to Greek audiences than the plays of Euripides. Just like the plays of Aristophanes were more popular than the plays of Aeschylus. You have always had art for art’s sake and art for the sake of education. Spike makes movies that enlighten people about issues. Tyler makes movies to entertain the masses. Both are legitimate goals. It doesn’t have to be one or the other.

And at the same time Tyler Perry has gotten to a rare place in the film community that comes with a certain amount of responsibility. Even though I think that no one has the right to criticize the kinds of stories that Tyler wants to tell or the caliber of filmmaking that is coming out of Tyler Perry studios, I’m about to contradict myself by saying that there are some things that need to be discussed about Perry.

Tyler Perry’s success has created problems for other African-American filmmakers. The Tyler Perry machine has lowered the bar for making movies. His craft and level of filmmaking is inferior and, generally, the stories are not good. Because his movies are so successful the industry is now looking at Tyler Perry as the model into which all black film makers must fit, and that is unfair. As a result, people who are trying to make different kinds of [black] movies are not being given the opportunity.

Tyler Perry’s success has created problems for other African-American filmmakers. The Tyler Perry machine has lowered the bar for making movies. His craft and level of filmmaking is inferior and, generally, the stories are not good. Because his movies are so successful the industry is now looking at Tyler Perry as the model into which all black film makers must fit, and that is unfair. As a result, people who are trying to make different kinds of [black] movies are not being given the opportunity.

Another problem is that the Tyler Perry model makes movies for small amounts of money in short periods of time. Not every story can fit into that mold. And because he has lowered the bar so much in terms of craft, the industry doesn’t care about filmmakers who want to make movies that take more money and more time.

The Tyler Perry situation has also revealed that the film community at large does not think of African-American filmmakers as individuals - it lumps us all into the same group. You would never ask Scorsese, Brian De Palma or Steven Soderbergh to make a Tyler Perry movie. But many black filmmakers are being told they have to make a Tyler Perry type of film.

Tyler has been extraordinarily successful. He is a tremendous business man. My hope is that he will use his clout and his studio to develop the works of other filmmakers. Because he has the studio and the ability to raise money he has a unique opportunity to develop and promote a talented pool of African-American filmmakers unlike anyone else in the history of film. Then we’ll all get the opportunity to see the richness, and the variety of voices that exist within our community.

BTM: In terms of volume, quality and influence, how would the state of black films in Hollywood today compare to what you have seen in years past?

WT: I think black films are in terrible shape today. 20 years ago… in 1991 there were 19 studio films released that were made by African-American filmmakers. This year we’ll be lucky if we have one or two. The model that produced that work 20 years ago does not exist today. There is no New Line Cinema, there is no Island Pictures. The independent film movement has been co-opted and destroyed by the studios. The studios are now run by corporations that are only interested in profits — not good storytelling. I suspect that the future will be in new media. People just have to figure out how to make money from it. I hope that with the success of films like “The Help” that the Hollywood studios will let us tell more of our stories. We’ll see…

BTM: What is your opinion of the state of black independent cinema? Are you pleased with what you see? Why or why not?

WT: Here’s my question to you, where is it? It seems that black independent cinema exists strictly for the entertainment of the black intelligentsia. It’s not available for the masses. You have to go to a film festival if you want to see those kinds of films. I work in commercial filmmaking so from where I am sitting it doesn’t really exist.

On some level the problem with independent film is that there is no distribution arm to distribute those movies. We have a problem in our film community. There are plenty of artists. There are plenty of people who want to be directors. There are a handful of people who want to be producers. There are a handful of people who want to be writers. There are plenty of people who want to be actors. The problem is that we are not developing people who are interested in the business side of show business. What we really need are people who are interested in the distribution of African-American films. We need our business community to pool their financial resources to create opportunities and venues where our films can be shown. Until we have distributors and the support from our own business community the state of [independent] black cinema will remain in the sorry state that it’s in today.

On some level the problem with independent film is that there is no distribution arm to distribute those movies. We have a problem in our film community. There are plenty of artists. There are plenty of people who want to be directors. There are a handful of people who want to be producers. There are a handful of people who want to be writers. There are plenty of people who want to be actors. The problem is that we are not developing people who are interested in the business side of show business. What we really need are people who are interested in the distribution of African-American films. We need our business community to pool their financial resources to create opportunities and venues where our films can be shown. Until we have distributors and the support from our own business community the state of [independent] black cinema will remain in the sorry state that it’s in today.

BTM: Recently, you were a part of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences International Outreach program, which “brings delegations of visiting film artists to countries with developing film industries (oscars.org).” How did that experience shape you as an artist and cultural ambassador?

WT: Going to Africa was an incredible experience. Meeting African filmmakers from around the continent was equal parts encouraging and exciting, because each of those filmmakers recognized their potential to tell stories that we haven’t heard before. Almost everyone we met who was working in the business (or who had the desire to work in the business) was filled with enthusiasm and dreams. They all seemed to have fresh, new stories that they wanted to tell. I was especially inspired by the film community in Kenya and Rwanda. What we discovered is that they don’t need us to teach them how to tell stories as much as share our approach to making movies and how we solve problems in the film making process. It was great being in a country where most of the people were black. That’s not something you get to experience in the United States. It was great meeting artists and filmmakers who realized that film is a tool that they can use to communicate with the world community. I was thrilled to be invited by the Academy to take the trip.

(l to r) Fabrice, Carol Littleton, Phil Alden Robinson, Stephanie Allain, Wynn ThomasJohn Bailey, Alfrie Woodard, Willie Burton, Ellen Harrington in Rawanda 2011

BTM: Thanks for your time, Wynn. Hopefully you and I will get the opportunity to collaborate on a film so that we can work to solve some of the challenges that you so eloquently pointed out.

The following Video was made by Danish journalist and film critic Steffen Moestrup.