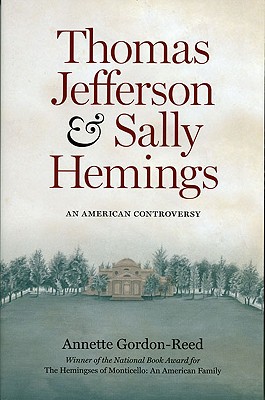

Annette Gordon-Reed

Biography of Annette Gordon-Reed

Annette Gordon-Reed is a professor of law at New York Law School and a professor of history at Rutgers University. She is the author of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy. She lives in New York City.

Questions for Annette Gordon-Reed (from Amazon.com)

Amazon.com: One stunning element to this story, for someone who

might only know its bare outline, is that these families, so intimately

related across the lines of race and slavery, were so even before

Jefferson's union with Sally Hemings: Hemings was not only his slave, but

also the half-sister of his late wife, Martha Wayles. (That fact alone could

provide enough drama for a hundred novels.) Could you describe the family he

married into?

Gordon-Reed: Well, it has been sort of a mystery.

Relatively little is known about Martha Wayles and her family life before

she married Jefferson, and even after her marriage. A historian, Virginia

Scharff, will be writing on this subject soon. But John Wayles, the father

of Sally Hemings, five of Sally's siblings, and Martha has been something of

a cipher. I tried finding out about him when I was working on my first book,

Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy. I broke off the

search because his life was not really the focus of the book, but I had to

come back to him for this one. It turns out he was apparently brought to

America as a servant, and was given a leg up in life by a prominent

Virginian named Philip Ludwell. Martha’s mother, also named Martha (it gets

confusing) died not long after she was born. Then she had two stepmothers

who died. The first had three daughters with John Wayles. After his third

wife died, Wayles had six children with Elizabeth Hemings, the last of whom

was Sarah (Sally) Hemings. Jefferson married a woman who had known a great

deal of tragedy in her young life. She had lost her mother, two stepmothers,

a husband, and child by the time she was 23, just unfathomable stuff from a

modern perspective.

Amazon.com: Of course, one other source of drama is that Jefferson,

at the same time that he was one of the greatest advocates for equality and

freedom, also held slaves, including one he was joined so intimately with.

How did he reconcile that to himself, if he did?

Gordon-Reed: I don't think this was something that

Jefferson agonized about on a daily basis. This is not to say it wasn't

important, but it didn’t concern him the way it concerns us. I think the

Federalists and the threat he believed they posed to the future development

of the United States concerned him far more. Jefferson was contradictory,

but we are, too. Who does not have intellectual beliefs that he or she is

not emotionally or constitutionally capable of living by? I find it more

than a little disingenuous to act as if this were something that set

Jefferson apart from all mankind. It's always easier to spot others'

hypocrisies while missing our own. He dealt with the conflict between

recognizing the evils of slavery, to some degree, by fashioning himself as a

"benevolent" slave holder and taking refuge in the notion that "progress"

would one day bring about the end of slavery. It wouldn't happen in his

time, but it would happen. That is not a satisfactory response to many

today, but there it is.

Amazon.com: What was Jefferson's relationship with his children with

Hemings like? What lives did they find for themselves after his death?

Gordon-Reed: That was one of the most interesting things to

research and ponder. There are a series of letters between Jefferson and his

overseer at Poplar Forest, his retreat in Bedford County, where he spent a

good amount of time during his retirement years. In those letters, he

announces his impending arrival. He'll say things like "Johnny Hemings and

his two assistants will be coming with me," and depending upon the year, the

two assistants were his sons Beverley and Madison Hemings or Madison and

Eston Hemings. Poplar Forest is 90 miles away from Monticello. That was a

journey of days together. Then, when they got there, John Hemings, Beverley,

Madison, and Eston would work on the house where Jefferson was staying,

where they evidently stayed, too. They were there together, in pretty

isolated circumstances, for weeks at a time. Jefferson, who fancied himself

a woodworker, too, spent lots of time with John Hemings and, in the process,

spent time with his sons, who were Hemings's apprentices. Madison Hemings

remembers Jefferson as being kind to him and his siblings, as he was to

everyone, but said he rarely gave them the type of playful attention he gave

to his grandchildren. The phrase Hemings uses is that he was "not in the

habit" of doing that. Yet, all the sons played the violin like Jefferson,

and one who became a professional musician, Eston, used a favorite Jefferson

song as his signature tune. We have little sense of his dealings with

Harriet, the daughter. He sent her away from Monticello when she was 21 with

the modern equivalent of about $900 to join her brother, Beverley, who had

left a couple of months before.

I think a very important, and telling, thing is that none of the Hemings

children had an identity as a servant. The sons were trained to be the kind

of artisans Jefferson admired the most, builders—carpenters and

joiners—and the daughter spent her time learning to spin and weave. Women

of all races and classes did that, even Jefferson's mothers and sisters.

Harriet Hemings wasn't turned into a maid for his granddaughters, which

would have been a natural thing for her but for her relationship to him. The

Hemings children were trained to leave slavery without ever developing the

sensibilities of servants. Beverley and Harriet left Monticello as white

people, married white people, and pretty much disappeared, although they

kept in contact with their nuclear family. When Jefferson died, Madison and

Eston, who were freed in his will, took their mother and moved into

Charlottesville. They were listed as free white people in the 1830 census,

and as free mulatto people in a special census done in 1833 to ask blacks if

they wanted to go back to Africa. They all said no. Not long after their

mother died, Madison left Virginia for Ohio and Eston joined him later. At

some point Eston decided that living as a black person was too onerous and

moved to Madison, Wisconsin, under the name E.H. Jefferson. He had children

by this time, and they all became Jeffersons. As all blacks who "pass" into

the white community must do, in later years the family buried their descent

from Jefferson. There was no way to claim him as a direct ancestor without

admitting that they were part black, which would have cut off all the

opportunities their children had as white people.

Amazon.com: Your title emphasizes Monticello, the rural retreat this

family shared. What was the household on "the mountain" like for the

Hemingses?

Gordon-Reed: Sally Hemings and her siblings along with her

mother were personal attendants to the Jefferson family. They worked in the

mansion most of the time. The next generation of Hemingses had more varied

experiences. They became the artisans working on the plantation. We get some

sense from Jefferson's legal white grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, that

some of the other people enslaved on the mountain were jealous of the

privileges that the Hemings had. Martin, Robert, and James Hemings were

allowed to hire their own time and keep their wages. They traveled to

Richmond, Williamsburg and Fredericksburg to do this. The only people

Jefferson ever freed were members of the Hemings family. They were people

who were treated as, and saw themselves as, something of a caste apart from

other enslaved people.

Amazon.com: How much of the evidence for this history has been

available for centuries, and how much has only become available to us in

recent years?

Gordon-Reed: Except for the DNA evidence showing a link

between the Hemings and Jefferson families, all of this information has been

available. I didn't discover or say anything in my first book that could not

have been said or discovered by others, and I haven't found anything for

this book that other people could not have found. It's always been there.

Amazon.com: And what are the limits of what we can know about these

lives? What have you had to imagine, especially about Hemings and

Jefferson's relationship, and how have you done so?

Gordon-Reed: Except for Madison Hemings, we don't have

personal accounts from the Hemingses of their lives. Robert Hemings

corresponded with Jefferson in the 1790s, but all of those letters are

missing. We have descriptions of what Sally Hemings did from others'

records—letters, census documents, things like that. As I say in the book,

that's pretty much what we have to go on with Jefferson and his wife too,

since we don't have any letters from her describing her life. Yet people use

what we have to come to a conclusion about the nature of their life

together. There's nothing wrong with that. I do the same thing for Jefferson

and Sally Hemings. It's a combination of what people said about their lives,

inferences from the actions they took, and a consideration of the context in

which they were living. Some people have problems with the use of

"inferences." I don't, so long as they are reasonable. In fact, I would

trust the reasonable inferences from a person's repeated behavior through

the years over what they say any day, because a people can say anything. I

do believe that actions often speak louder than words. Contrary to popular

belief, there are lots of actions on the part of Jefferson and Hemings that

"speak" about the basic nature of their relationship.

Are you the author profiled here? Email us your official website or Let us host your primary web presence.