Wendy Jones

Biography

I come from a family of storytellers. My mother and my grandmother were my first teachers. Around the kitchen table, on a Harlem street corner talking to a neighbor, or over the phone with one of her sisters-she had six-I heard my mother’s stories. Here she is complaining about a meddlesome co-worker: “And then Katrina put her two cents in.’

Listening to Mama and my adult cousin in conversation, I followed the path of their talk as they moved from subject to subject. “>She started looking sickly around November.” “Ching Chow had two fingers up, so two is gonna be the first figure.” “I told Morris to get off the phone or he was going to eat breakfast alone.” I was learning how to write dialogue.

My grandmother, on the other hand, was rarely in dialogue with anyone. Big Ma delivered sermons. One summer when I was visiting South Carolina, she declared in rolling, deep tones while discussing my aunt and her family in New York, “They left with nothing but the clothes on their backs.” The family had been evicted from their apartment as a result of “Negro removal,” what black people in the ‘60s called urban renewal.

When my youngest aunt insisted that the questionable man she wanted to marry was a respectable bricklayer, Big Ma ended the argument in one sentence: “Benny ain’t never laid a brick in his life unless he picked it up and threw it at somebody.”

Not only did I have the rich feast of this oral tradition, but I was also a voracious reader. I read Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, de Maupassant, Fitzgerald, Baldwin, Langston Hughes, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, Paule Marshall, and Zora Neale Hurston.

Until I was about nine, I thought that books were born, like people. Once I realized they were written, I decided to become a writer. Mixing autobiography with imagination, I wrote stories that took me, along with my cousins, on spaceship adventures. In fourth grade, combining fairy tales, “Rapunzel and Aladdin’s Lamp,” I entertained my kindergarten friend on the school bus.

In high school, my English teacher told me I had an “ear for dialogue.” I continued writing in college and won a prize in a short story contest. For my senior year, as part of an independent study program, I wrote a novel instead of attending classes. Although I finished the novel with revisions before the deadline and received a year of academic credit for it, it was not a good novel.

I did not know my main character well enough to write from his viewpoint. But I discovered I could wake up every morning staring at a blank page and fill it with life by evening.

Whenever I listen to interviews with writers or attend my library’s book club, interviewers and readers seem fascinated with the autobiographical aspects of a novel. To me that makes no sense. It is the imaginative threads of the tale that make it a work of fiction. That is where the art, the beauty is. Also, because the writer puts her- or himself inside the character, the story tells the truth the way no non-fiction treatment of the subject can. Fiction tells the emotional truth.

That is why Toni Morrison’s Beloved is so stunning. She makes us feel from the inside what would make a mother kill one child and try to kill the others rather than allow them to be enslaved. Despite our empathy, we see that even a mother does not “own” her children and has no right to decide whether they should live or die. Even more crucial, Morrison shows us that the inability to turn to the community for help in times of need signals the death of a person’s humanity.

Years after college, I went to Columbia and earned an MFA in Fiction. The degree was not my primary goal: I wanted to spend two years focusing on fiction. Building up a stockpile of work, I polished what I had and have been adding new work through the years.

Although I am primarily a writer of fiction, it is my non-fiction work that has been widely published so far. My first play, In Pursuit of Justice: A One-Woman Play about Ida B. Wells, starring Janice Jenkins, won four AUDELCO Awards. [Ms. Jones’ short story, “Savannah,” also appeared in 1996 in the anthology Illuminating Tales of the Urban Black Experience (Penguin Books).]

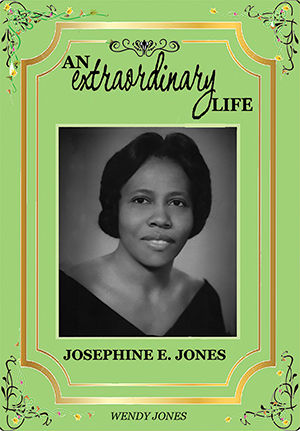

My first book was published this year, An Extraordinary Life: Josephine E. Jones.

This is the biography of my mother, a South Carolina sharecropper’s daughter, born in 1920, who journeys to New York in 1946 to work as a cook in private homes. By 1967, she is not only a Harlem activist, but also the first black woman in management at a Fortune 500 company, Standard Brands, now KraftHeinz.

Josephine’s voice is the heart of the book with my voice adding historical context at the beginning of each chapter. Also included is an appendix describing how my mother nurtured my education.

Listen to an Interview of Wendy Jones Interviewed by David Rothenberg on New York City’s WBAI’s “Any Sarurday” July 8, 2017

I am looking forward to your response to this compelling story. As you will find when you visit the website (below), or you can contact me at idabellpub@gmail.com.

Learn more at Wendy Jones’s official website.