“How I Came to America” by Elizabeth Nunez

Elizabeth Nunez immigrated to the United States, from Trinidad, in 1963. In 2019 America, an era of heightened xenophobia, it is important to remember that America is a nation of immigrants. Many of the immigrants in America today owe the privilege of citizenship to the fight waged by activists during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Here is her story…

“I managed to come to America because good white people opened the doors for me. That was all I knew when I arrived here, from Trinidad, for the first time, in 1963, on a student visa. It was all I knew when I was given a Green Card, permanent resident status in the USA, in 1968. It was all I knew until I joined the faculty at Medgar Evers College in 1972 and discovered that all I knew was the tip of the iceberg, most of it a lie.

I was 19 in 1963, the third of eleven children, born and raised in Trinidad, a country, until only a year before, a colony of England. Being female, with a brother just ten months younger, I clearly understood that if the family’s fortunes were to be spent on higher education, the money would go to him, not to me. So, of course, I felt that I had hit the lottery when an American missionary came to my home offering me a full scholarship—tuition, books, board—to a Catholic college in Wisconsin.

In 1963 I knew next to nothing about America. In school, in Trinidad, I had learned only about those places, where, as Winston Churchill boasted, ‘the sun never set on British soil’. In snow-bound Wisconsin, no one chose to point out to me that in September of 1963, when I entered that all-white college, in that all-white town in Wisconsin, four little girls were murdered in the fiery explosion of a bomb thrown inside a church in Birmingham, Alabama, by racists who hated people who looked like me. And when the academic year ended, in June of 1964, no one mentioned that the bodies of the young civil rights workers Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner had just been unearthed out of a shallow grave where they had been hastily buried. Perhaps I had heard the news fleetingly on the radio or television; perhaps my eyes had scanned a report printed deep inside the local newspaper, but, like everyone else around me, I gave little notice to these happenings. I had a scholarship; that was all I cared about. In four years, I would return to my homeland. What was happening in America was not my business.

But then, in 1968, after a year back in Trinidad, I found myself bored, resistant to the expectation that women my age should marry. On a whim, I went to the US Embassy and applied for a Green Card. In less than three months I was called for an interview. The American man who interviewed me was white. I remember he was also fat, his face flushed and sweaty from the heat of our tropical sun. He was smoking a cigar and thick smoke filled the small room where we sat.

‘Do you know anyone in America?’ he asked me.

‘No’, I answered.

‘Do you have a job in America?’

Again, I answered in the negative.

‘Do you have money in the bank?’ he asked.

‘A little’, I said. ‘Four hundred dollars.’ [$400 TTS was equivalent to $60 USD]

He shook his head and walked out of the room. But 15 minutes later, he was back. ‘What will you do in America?’ he asked.

‘Find a job’, I said. ‘Teach.’

‘Where?’ he wanted to know.

I responded vaguely that I had a BA degree from an American college, and for the past year, I had been teaching in a high school in Trinidad. Was my response so persuasive as to convince him of my eligibility? What else was there for me to assume when he left the room abruptly only to return this time with stamped papers for me to sign?

I had to leave in two months, he said. God bless America.

And, indeed, God blessed America and America blessed me. I did not stop to think why that white man had been so kind to me. Soon after I arrived in New York, I found a job, not teaching to be sure; one had to have a special license for that. But the Vietnam War was still raging, and with young men dying in the hundreds of thousands, many more thousands drafted weekly, there were job openings everywhere for anyone willing to work. During the day I earned money to feed, clothe and house myself; at night I went to graduate school. Soon I was fulfilling the American Dream. I had my own apartment, my own car and enough money to make several trips back to Trinidad bearing American gifts for friends and family. Like most immigrants, I was proud of my achievements, proud of what I had accomplished on my own. If there was anyone I had to thank for my good fortune in America, it was the white people at the college in Wisconsin who had given me a scholarship, and the fat, white man in the American Embassy in Trinidad who had taken a chance on me. It had certainly never occurred to me that both of them—my white benefactors in Wisconsin, the Santa Claus in the Embassy—had been coerced into their magnanimity, that it was to black America I owed my good fortune.

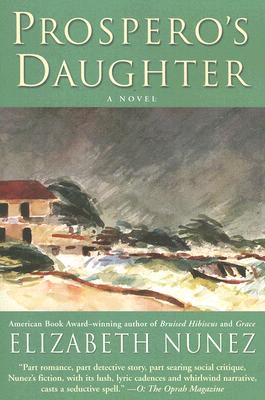

In 1999, Seal Press, a small independent company in Seattle, published my second novel, Beyond the limbo Silence, which had been passed over in the late 1980s by Putnam, the publisher of my first novel, When Rocks Dance, and then for several years by other publishers. The novel subsequently won the 1999 Independent Publishers Award. It was also selected as the work of fiction for the 2004 CUNY Is Reading program intended to stimulate discussions among the 100,000 plus students and faculty at the City University of New York. Perhaps the publishers had balked at the story I told in Beyond the limbo Silence: Sara, a young woman from Trinidad, is given a lesson on the harsh realities of racism in America by a male African American civil rights worker who is visiting the all-white town in Wisconsin where she is a college student. The African American tells Sara that while she sits comfortably in her classroom, young black men and women are being attacked by snarling police dogs and hosed down by jets of water with the power to strip bark off trees. Not quite the story that a generation which placed a premium on optimism and was doggedly determined to put the horrors of the twentieth century behind it wanted to hear in the 1980s.

In 1999, Seal Press, a small independent company in Seattle, published my second novel, Beyond the limbo Silence, which had been passed over in the late 1980s by Putnam, the publisher of my first novel, When Rocks Dance, and then for several years by other publishers. The novel subsequently won the 1999 Independent Publishers Award. It was also selected as the work of fiction for the 2004 CUNY Is Reading program intended to stimulate discussions among the 100,000 plus students and faculty at the City University of New York. Perhaps the publishers had balked at the story I told in Beyond the limbo Silence: Sara, a young woman from Trinidad, is given a lesson on the harsh realities of racism in America by a male African American civil rights worker who is visiting the all-white town in Wisconsin where she is a college student. The African American tells Sara that while she sits comfortably in her classroom, young black men and women are being attacked by snarling police dogs and hosed down by jets of water with the power to strip bark off trees. Not quite the story that a generation which placed a premium on optimism and was doggedly determined to put the horrors of the twentieth century behind it wanted to hear in the 1980s.

Though to some Beyond the limbo Silence reads like autobiography, the truth is I did not have Sara’s good luck. No one had told me these facts. But all through my years in Wisconsin, I felt a sense of unease, discomfort, that grew to a pitch that was so intolerable I could not bear to spend a moment longer in that college, in that town, after I turned in my last exam in my last class. What was the source of that unease, that guilt? For guilt it was, though I could not give it a name, so impenetrable was the silence around me. What I knew was that on my first trip out of that all-white town in Wisconsin, the Greyhound bus I had taken swept past the outskirts of Milwaukee and for the first time I saw African Americans in America in such numbers that I could not suppress the question that continued to haunt me for the rest of my college years: why me? Why had these white Americans in Wisconsin gone 3,000 miles overseas to get me, a black girl from Trinidad, when 30 miles away there were black people eager as I was for a fully-paid college education?

Medgar Evers College would answer that question for me. In 1972, I gave no particular significance to its name. I had no idea that a young husband, a father of small children, had been callously shot in his driveway in Mississippi as he was returning home after working all night registering African Americans to vote. I had no idea that the very existence of that college was the result of a struggle to force the hand of the City University of New York to provide higher education for the city’s under-served black population. I was an immigrant, living the American Dream. What I had achieved, I had achieved on my own, as a result of my hard work.

I know I am responsible for my ignorance, but in all my years living in America, in spite of four years of undergraduate education and eight years of postgraduate education, not a single American ever pointed out to me the connection between the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Immigration Act of 1965. Not a single American ever urged me to note that the distinctive feature of the Immigration Act of 1965 was that it removed ‘national origin’ as one of the criteria for obtaining a visa to immigrate to America.

At a recent conference on immigrant writers, a prominent immigrant writer of color, in her keynote speech, told us that Robert Kennedy was responsible for the Immigration Act of 1965, and, therefore, immigrants of color are indebted to him (and by implication, to white America) for opening up America’s doors to us. I acknowledge the heroic efforts of Robert Kennedy and those of many good white Americans, but the simple truth is this: without the passing of the Civil Rights bill, it is unlikely that the laws affecting the immigration of people of color to the US would have been changed.

It should have been a no-brainer for me to understand how my good fortune was linked directly to the struggles for racial equality in America, but it was only recently, in the process of doing research for one of my classes at Medgar Evers College, that I made the connection. In 1964, the Civil Rights Bill ending racial discrimination was passed. One year later, in 1965, legislation removed the national origins quota system as a criterion for immigration. Until this bill was passed, the annual quota for all of Asia was 2,900, compared with 149,667 for Europe and 1,400 for all of Africa. Why did the white American man give me a Green Card so easily in 1968? I know the answer now. Though the criteria for immigration were revised in 1965, the new regulations were not implemented until 1968. Racism was so entrenched in America that it took the assassination in April 1968 of a great African American, Martin Luther King, Jr. to send embassies in a scramble to meet quotas left unfilled since the passing of the new law. When I walked into that US Embassy in Trinidad, that cigar smoking red-faced man was actually happy to see me.

Too many immigrants of color do not acknowledge their debt to African Americans. By immigrants of color, I am referring to all those, who, because of the removal of the criterion regarding national origin from the Immigration Act of 1965, have enjoyed the opportunities that America has to offer: people from the Caribbean, Africa, Latin America, Arab countries, the Middle East, South East Asia, India, Korea, Japan, China, etc., etc. Even immigrants from Eastern European countries, given America’s preference for Western Europeans, have benefited from the struggles of African Americans for racial equality. I know who opened the doors for me to America. I know when I stepped through those doors my feet sank in a pool of blood. Too often, I think, immigrants of color are ignorant of this history. Too often they distance themselves from the ongoing struggle by African Americans to end racism directed toward them.”

This article, by Dr. Elizabeth Nunez, was originally published in 2005 in Changing English, 12:3, 373-376, DOI: 10.1080/13586840500346147

Dr. Elizabeth Nunez, 2018

Dr. Elizabeth Nunez, 2018