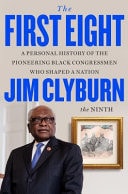

Book Review: The First Eight: A Personal History of the Pioneering Black Congressmen Who Shaped a Nation

Reviewed by:

Robert FlemingSouth Carolina Congressman Jim Clyburn’s The First Eight: A Personal History of the Pioneering Black Congressmen Who Shaped a Nation provides the type of history that the current administration would love to erase. Previously serving as a majority whip in the U.S. House of Representatives, Clyburn has exerted his influence for more than thirty years as a determined activist for equal and civil rights. In 2022, he was awarded the NAACP’s lofty honor, the Spingarn Medal. Last year, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the United States. With all his political experience, the activist and lawmaker tells the triumphant tale of the first eight Black men who braved a tidal wave of challenges and obstacles in this hybrid of history and personal chronicle.

Standing on the shoulders of these courageous politicians from South Carolina, Clyburn salutes the men who rose to prominence after the Civil War and Emancipation, possessing the elements of focus, purpose, vision, and hard work. The eight Congressmen came from the cruel Middle Passage, from a blend of free Blacks and enslaved souls, surviving in the antebellum state. Clyburn singles out the extraordinary achievements of this group: Richard Harvey Cain, Robert Brown Elliott, Robert Carlos De Large, Alonzo Jacob Ransier, Thomas Ezekiel Miller, Joseph Hayne Rainey, Robert Smalls, and George Washington Murray.

A highlight of the book occurs when the author praises Smalls as “the only bona fide Civil War hero of the Eight and only one of two Blacks attending as a delegate to the 1868 and 1895 Constitutional Conventions,” granting and then revoking Black political and civil rights in the state. When historians examine the period of their rise, they speak of the turbulence and violence of those years, a measure of their resilience and intellect.

In the introduction, Clyburn writes: “Like all of us, the First Eight were not perfect. But they rose to the challenges of their time, determined to demonstrate by example that race does not define one’s humanity. They knew that until America lived by its founding principle of ‘liberty and justice for all,’ our country could not achieve its democratic ideals.”

Of the Eight, Smalls defied slavery, which earned a lion’s share of the state’s business, more profit than the original thirteen colonies. He worked as a stevedore on the ship The Planter, where he concocted a plan to take it with his family and go toward freedom. His bold escape was celebrated by the North, and the man showed his patriotism when he piloted the now armed ship against Dixie, again and again. However, the First Eight, using the power of community and political opportunity, extended the right hand of fellowship to all, holding “no hatred or malice toward those who have held our brethren as slaves.”

In the political chess game, some whites argued a set of regulations should be enacted “to protect African Americans from the dangers of their own ignorance,” termed the Black Codes. These codes were designed to keep Blacks in their place. With the South departing the Union, De Large, Ransier, and their compatriots triumphed, passing the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Fourteenth Amendment, which nullified the Black Codes.

On the other hand, racist whites acquired the names of members of Republicans, both Black and white in the rise of the Klan. One member shot and killed Benjamin Randolph, the Black Republican chair, in daylight. On the eve of the election, hooded Klan patrolled Black neighborhoods, preventing them from going to the polls. According to Clyburn, there is still a sizable Klan influence there, which has to be monitored.

Despite the legal miscues by the past and current administrations and the Supreme Court, Clyburn writes of this timely history lesson: “I support the rule of law, and because the United States is a democratic nation, we must abide by the Supreme Court decision. Yet I am reminded that the high court is not immune to partisan and popular influence and has a history of issuing decisions that have had horrific consequences for people who look like me. Indeed, in their years of service to come, members of the First Eight would suffer from the fallibility of the American legal justice system.”

In his closing words, Clyburn, the Ninth, sums it up, linking the Klan and the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers under the MAGA regime: “The refrain ‘Anything that has happened before can happen again’ may have more currency for me and my colleagues today than it did back in the 1960s, when I repeated it to my students almost daily…. We must safeguard our collective rights and our democracy. As the arc of history during the First Eight’s lifetimes shows us, there are no guarantees; freedom can be fleeting.”

A hybrid of Reconstruction Era and current history, The First Eight peels back the oft-forgotten political and cultural times to expose the lows and highs of Washington antics. Clyburn’s narrative style is scholar-like, such as that of an academic professor or an historian. In this thoughtful biographical book, he lets the facts speak for themselves. This book is a fitting tribute of the organizational skills, inner strength, grit, and imagination of Black political representatives throughout the years. This history must be embraced.