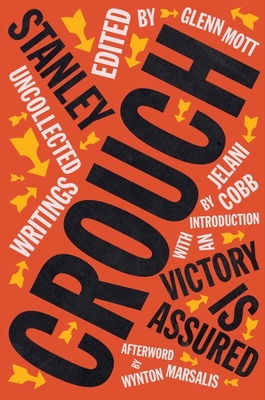

Book Review: Victory Is Assured: Uncollected Writings of Stanley Crouch

Reviewed by:

Robert FlemingLarger than life, controversial scribe Stanley Crouch loved to throw shade, raise hell, and put himself laughingly in the crosshairs. In the golden age of New York City’s literary elite during the eighties and nineties when the meek were grinded to dust, he always made a big noise. His critics complained about the “combative, never averse to attention, and a virtually insatiable appetite for controversy” of his writing. Yet before his death in 2020, the often ornery writer made his mark in several genres: poetry, music, cultural criticism, televised personality, novelist, and biographer.

A native of South Central, he attended junior colleges and worked for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee during the civil rights campaign. Following a tenure of teaching theatre and literature at Pomona College in 1975, he released a poetry book, Ain’t No Ambulances For No Nigguhs Tonight, and later moved to New York City as a jazz drummer in a band with tenor saxophonist David Murray. He knew he was not a good drummer, but found solace on a blank page. His writing consists of one novel, Don’t the Moon Look Lonesome? (2000), and including several nonfiction works such as Notes of a Hanging Judge: Essays and Reviews 1979-1989, The All-American Skin Game or The Decoy of Race, The Artificial White Man, Considering Genius: Writing on Jazz, and a biography, Kansas City Lightning: The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker. The high quality of his writing earned him many awards like a Guggenheim Fellowship (1982), Whiting Award (1991), MacArthur Fellowship (1993) and a Fletcher Foundation Fellowship (2005).

In this latest book, Victory Is Assured, readers will be treated to a stunning assortment of Crouch’s achievements: critical essays, profiles, articles, liner notes, reviews and eulogies. Published after his death, Jelani Cobb, one of his former students and current dean of Columbia Journalism School, writes in the introduction: “…but there was Stanley on the page, concussive and rhythmic, brutal and beautiful, hands as heavy as his feet were light.”

These pages are full of Crouch’s obsessions of jazz, politics, film, and culture. An enemy of gangsta rap, he agreed with writers Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray about the traditional, classic jazz and criticized avant-garde jazz and fusion. Witness the snarky titles of involving America’s Original Music, Jazz, in some of his premier pieces: “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Dues: Duke Ellington at Disneyland,” “Fusionism: Wayne Shorter and Dexter Gordon,” “Laughing Louis Armstrong,” and “Jazz Lofts.”

According to Crouch, there was some degree of slick armchair quarterback regarding pianist Thelonious Monk in his piece, Saint Monk: “Through no one knew that Thelonious Monk would soon have that inevitable meal my grandmother called “breakfast with the moles,” there had been a Monk fever in the jazz world for at least two years before he died.”

On the elegant songstress Billie Holiday in “A Song For Lady Day,” Crouch could touch on some of universal truths regarding the Queen of Heartbreak:

So the will to live becomes more than desperation and ascends to a combatively affirmative morale. No minor accomplishment, this may be the most impressive thing that American Negroes have offered the world at large. There can be no doubt that Billie Holiday knew how to bring it.

Translating his twisty read on horn man Miles Davis, the writer brings his own juju to the musician’s art, “Miles Davis, Romantic Hero:”

Little, dark, touchy, even evil, Miles Davis walked onto his bandstand and made public visions of tenderness that were, finally, absolute rejections of everything silly about the version of masculinity that hobble men in either the white or the Black world.

Politically able to shift viewpoints, Crouch’s righteous vision took in the bold stance adopted by Blacks bent on mayhem during the ghetto uprising in “When Watts Burned:”

The police were obviously frightened – these Black people did not avert their eyes, did not tremble and stutter, but stared into their white faces with a confident cynicism, a stoic rebelliousness, even a dangerous mischief. This was unusual for Los Angeles Blacks, who long before had literally whipped into shape by Chief Parker’s thin blue line, a police force known in the community for shooting or clubbing first and asking questions later. No one was afraid of them now ….the police did not understand.

Analyzing one of Hollywood’s 1942 corrupt Dixie melodrama, Crouch exposes a film which didn’t get a proper viewing:

Starring Bette Davis, perhaps the greatest white bitch of them all, under the direction of John Huston, surely one of our finest directors, In This Our Life provides recognition of how southern bigotry functioned just before World War II. It also clarifies how its casual presence in the daily lives of southern whites had become so natural that ill intent seemed absent.

In his Voluptuary commentary, the writer penetrates the Negro female beauty template of the preference of “our women big, with plenty of sensual wobble.” He mentions fleshy gals Anna Magnani and Bessie Smith in the same piece. With tongue in cheek, he offers this: “Some men know just what was meant when a woman was proud of every ounce of her flesh and sent forth a beam of confidence that signaled she had plenty of intimate charms. Such women used to say when teased about their weight, “Nobody loves a bone but a dog.”

Loving to go against the stream of popular opinion, Crouch, a former biweekly New York Daily News columnist, sticks his thumb into the eye of the Black community in a 2010 column, ”Then And Now, I Am A Negro:&rdquo

Those so willing to pretend that they are Africans and not Americans or who claim their Americanness almost as a unavoidable burden are just caught up in another meaning less trend that has been swallowed by the country as whole. Freedom of choice is finally the point, above all else. We are, after all, Americans.

What Crouch left uncollected and sometimes unpublished is presented here in his posthumous work, Victory Is Assured, as a wide range of cultural and political topics like a shiny Macintosh apple containing a razor blade given as a Halloween treat. The pieces are supposed to have a serious bite and provoke thought. Crouch loved to be considered a mean bastard. However, his writings, with all his venom and artistry, are not to be taken lightly.