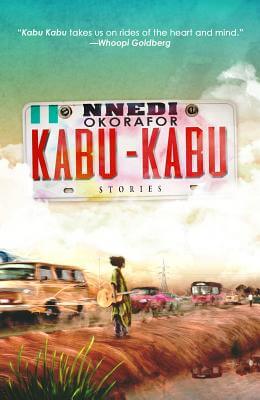

Book Review: Kabu Kabu

Reviewed by:

Robert FlemingAmerican-Nigerian author Nnedi Okorakor’s first short fiction collection, Kabu Kabu, takes the reader by surprise, with its heady mix of fantasy, science fiction elements, and regional folklore and myths. One thing the author does is to keep the culture, history and traditions of Nigeria up front, while stressing the challenges and obstacles faced by women and her people worldwide. For those who only know the classics written by the master Nigerian scribe Chinua Achebe, there is a wealth of writers from the area, such as Elechi Amadi, Sefi Atta, and two of my favorites, Buchi Emecheta and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Add Nnedi Okorafor to this esteemed group.

With a neon explosion of images and effects, the collection begins with

“The Magical Negro,” where the author turns the myths of black Africans

upside down in a way of irony and wisdom not seen since Zora Neale Hurston

did so with her tribe. A Nigerian taxi driver takes center stage in her

tale, “Kabu Kabu,” where Ngozi, a lawyer, rushes to the airport for a madcap

flight to Nigeria for her sister’s wedding. Okorafor, with an assist from

science fiction legend Alan Dean Foster, penetrates the male mindset of a

certain traditionalist who buys into everything that is scary for the young,

staid up-and-coming female attorney.

Some critics have bashed her for her over-reliance on African folklore and

mythology. With me, it was refreshing to see how far she went in making the

characters, situations, and drama surrealistic and totally dada. For

instance, Okorafor stirs the pot with a mash-up of a trickster tale and

Hammer horror magic with two creepy stories, “On The Road” and “Long Juju

Man,” complete with big green lizards, ghosts who nibble on bad fruit, and

tribal sorcery. Great stuff.

If anyone knows about the nature of conflict in Africa, it’s usually tribal

and often religious, especially as in Biafra or Rwanda. Here Okorafor

addresses in the somber “The Black Stain,” where two tribes, the Uche and

the Okeke, doing battle over the embrace of technology by the latter.

Progress vs. the traditional. Both risk extinction through their blind

actions, through their lack of tolerance and acceptance of the other.

Maybe Okorafor included the snippets of the Windseekers tales into this book

to give them proper perspective. I love the myth behind these searchers,

with their dreads, open hearts, and the perpetual quest to find the right

one. That’s the reasoning behind “The Winds of Harmattan,” where Aunt

Asuquo, a Windseeker, tries to locate her soul mates despite a strong libido

which keeps getting in the way. If the Windseeker doesn’t find the chosen

mate, he or she perishes.

One of the strongest qualities of African literature is that it gives you

the feeling of intimacy as if the griot or teller is speaking quietly to you

as one of a selected circle of listeners. Orkorafor conjures up that

feeling. Two of my favorite stories here, “Biafra” and “Icon” deal with the

topic of genocide and the subject of oil, told from inside out. They

are matter-of-fact, sometimes brutal and raw, and do not dodge the reality

of tribal conflict or greed.

Finally, Okorafor doesn’t turn her back on any of the current hot button

issues. She tackles the controversial topics of greed, gender, sexuality,

politics, nationalism, technology, the depletion of the earth’s resources,

fear, blood ties, conformity, and conflict. On the heels of the acclaimed

Who Fears Death, Okorafor has done herself proud and should acquire many

readers with this sterling effort.