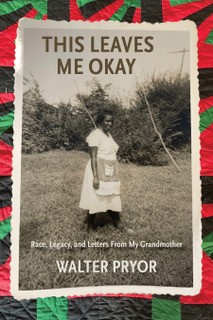

Book Review: This Leaves Me Okay: Race, Legacy, and Letters From My Grandmother

Reviewed by:

Ahmad WrightIt is not every day that your grandmother writes you a letter. Even rarer for a grandmother with an eighth-grade education to write periodically in her own hand over a long span of time, for almost thirty years, for the duration of a life. For author Walter Pryor, his book This Leaves Me Okay: Race, Legacy, and Letters from My Grandmother not only affirms a window into another era, but his grandmother’s letters lead the reader to points of entry for a historical narrative of his grandmother’s life. They also allow for an adjacent context for Pryor’s own voice in alternating and adjacent chapters that bridge Grandmother Lucille Hatch Eldridge, affectionately known as “Mama Ceal,” from her family’s past and Arkansas roots to the present.

Grandmother Lucille’s tale is told in a story format starting from her time as a little girl living in Casscoe, Arkansas, in the 1920s. Pryor’s narrative accounts of his grandmother and great aunt’s formative years include constant movement between the homes of extended family and introduce the reader to the various levels of trauma that shape Lucille’s future. She and her younger sister Dessie Mae were moved from their parents, Tommy Hatch and Leola Nobles Hatch, when she was four years old when her mother died of cancer. Then, the two sisters were shuffled briefly to Tommy’s parents, Edward (Papa Ed) Hatch and Liza (Mama Liza), twenty miles away in Almyra, Arkansas. Next, they were taken in by Leola’s abusive brother Jerry and his wife, Beulah, for a short time until Lucille and Dessie Mae’s father Tommy, now a widower, “stole” them back to his parents.

Their “older and lighter” Cousin Elizabeth, the daughter of Tommy’s sister Emma, lives with Papa Ed and Liza as well. She would become a major feature in Lucille’s life for many years to come. The telling of these memories in the early pages of the text are vivid and present. Family details of relationships and connection provide a genuine sense of what life was like during these times in rural Arkansas for Black folks of varying shades, degrees of poverty, and moments of uplift.

As Lucille reaches certain life milestones, such as her marriage to Walter Eldridge in 1935; the birth of her daughter, LaRuth; LaRuth’s formative years living with Lucille’s cousin “Aunt” Elizabeth and her husband, Owen, so she might receive a better education; the start of Lucille’s work as a maid for the white Horton family and all activities in-between; and the ripple effects of these occurrences leave insight to what Pryor’s grandmother endured to keep her family together the best way she could.

Likewise, through intermingled chapters, we also experience the author Walter Pryor’s response to his grandmother’s narrative juxtaposed against his own memories. This includes an internal debate comparing his grandmother’s time-period and his own. He considers an era where code-switching, changing one’s tone and attitude in mixed company, “was accepted as the way things were” in his grandmother’s time. Still, in his own time, “I had figured out that adopting the speech and behavior that seemed to be attributed to Whites was at least a pragmatic thing.” Pryor’s chapter topics include unwritten rules concerning extreme racism in early twentieth-century America to the civil unrest and protests following the murder of George Floyd in 2020 and its impact on his own family dynamics today; they include comparisons between his own sense of light-skin privilege, and his place in a professional class, to his grandmother’s perseverance and grit in the rural South as a woman of darker hue.

Social justice, personal pain, and reconciliation share pages through calculated reflection. Included in the pages of the book are photographs and Mama Ceal’s letters leading up to Pryor’s 1990 graduation from Georgetown Law School that reflect the elation at the prospect of her grandson’s professional path. Similarly, we witness her steadfast connection to her longtime friend and employer Mrs. Della Horton and her family, the prominent business and landowners of New Castle, Arkansas, who offered her employment as a maid after her husband, Walter, died; and the final commentary by Pryor on the strained relationship between Mama Ceal and his mother, LaRuth.

Pryor’s memoir was an enjoyable read. Much of the book is extrapolated from his grandmother’s letters and other sections are memories from the author. The vivid descriptions of events and lively dialogue held my attention from the start. Together these elements are “collected” for the sake of those chapters of the grandmother’s life that read like a novel. The letters are the pieces of history that link the two people. Readers can expect an intimate narrative with insightful reflection.