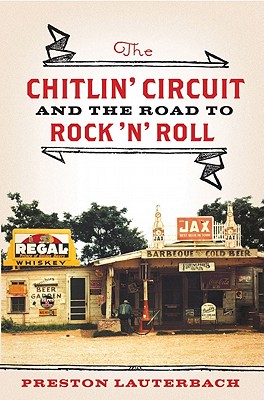

Book Review: The Chitlin’ Circuit: And The Road To Rock &rsquoN&rsquo Roll

Book Reviewed by Robert Fleming

It’s a shame that nothing substantial has been written about that sacred

Black entertainment network of the Jim Crow South known as the Chitlin’

Circuit. Preston Lauterbach, a music journalist based in Memphis, has done

us a great honor by revisiting this collection of clubs and joints in small

towns and cities from Alabama, Louisiana, Texas, Tennessee, Mississippi,

Georgia, Oklahoma, and other places below the Mason-Dixon line in this new

book, The Chitlin’ Circuit and the Road to Rock ’n’ Roll.

With a snappy, lively feel to his narrative and rare photos, Lauterbach

describes the Chitlin’ Circuit, which was established in the 1930s, was

exploited by a gangster-club owner Denver Ferguson and a stylish bandleader

Walter Barnes. Readers of the Chicago Defender, one of the leading

Black publication of the day, savored Barnes’ accounts of his band’s

exploits on the road where the colored and sometimes white folks gathered in

the segregated South for music and dancing not to be found in the stodgy

mainstream clubs.

"In the South, there was nothing but farming; tobacco fields, rice fields,

sugar cane, cotton fields," Sax Kari, one of the those people familiar with

the circuit. "Black people worked all week and Saturday night was their

night to howl, get drunk, and fornicate."

Every place in the Black areas had its "stroll," with the people of color in

control of the commerce and accommodations. When Black performers went to a

city or town, they could always be assured to find a place to rest and eat

rather than being turned away by white bigotry. Frequently, they honed

their craft in these places, trying out new arrangements and songs.

The Chitlin’ Circuit was a raw and raucous place. Many of these "nighteries"

had a sinister, criminal feel and the moneyed moguls controlled the Black

music business. The author writes about their power, saying "their number

rackets, dice parlors, dance halls, and bootleg liquor and prostitution

rings financed the artistic development of breakthrough performers."

Some of the stars, which Lauterbach presents in colorful anecdotes, were:

Louis Jordan, Little Richard, Redd Foxx, Jimmie Lunceford, B.B. King,

Butterbeans and Susie, T-Bone Walker, Johnny Ace, James Brown, Aretha

Franklin, Same Cooke, and others. Eventually, the World War II heyday of the

swing and dance orchestras gave way to the rise of small combos and later

blues and R&B groups. The circuit finally rasped out its last breath with

the push of integrated clubs during the civil rights era of the 1960s and

1970s.

What Lauterbach’s revealing account of the Chitlin’ Circuit proves it is

false and misleading to believe that this network of jukes, road houses, and

clubs was somehow inferior to any "quality" white establishment. Well

researched and engrossing, this book is an education to anyone who is

interested in African-American musical and cultural history.