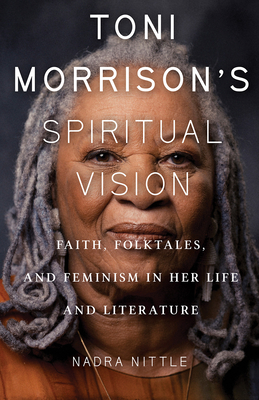

Book Review: Toni Morrison’s Spiritual Vision: Faith, Folktales, and Feminism in Her Life and Literature

Book Reviewed by Robert Fleming

When literary icon Toni Morrison died in August, 2019, world literature lost a rare creative mind, with a maverick attitude which did not prevent her from enjoying commercial and critical success. She earned acclaim with the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1977 for Song of Solomon, awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Beloved in 1987, and later received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1993. Her writing explored the complexities of racism and discrimination in her community and nationally.

Journalist Nadra Nittle, author of Recognizing Microaggressions (2019), acknowledges the author’s spiritual depth in her work, along with her loyalty to her community and gender in her Toni Morrison’s Spiritual Vision: Faith, Folktales, And Feminism In Her Life And Literature. Her embrace of religious themes rounds out her texts, especially African and African-American traditional myths and folklore. Although she was a devout Catholic, she borrowed the faith of her mother, who worshipped the Holy Book as a member of the African Methodist Episcopal church. A reader, she welcomed the intricate tales of horror, supernatural, and romance from her parents, with a liberal dose of Jane Austin and Leo Tolstoy. With the publication of her debut novel, The Bluest Eye (1970), Morrison created the work “without the white critic sit on your shoulder and approve it.” She wrote her books for black people unlike Baldwin, Ellison, and Wright, who welcomed white approval.

The religious fundamentals were supported by her grandfather reading the Bible cover to cover, stressing its importance as “taking power back.” Nittle noted that Black America considered the Bible as a document of liberation, along with West African oral, spiritual and folkways. In her analysis, the novelist formed a literary world where the supernatural and the church could co-exist in an environment of race hate and misogyny.

Morrison often said about her books and life: “faith in the invisible — be it in God or in magic — makes the world larger for African Americans.” An example of this was the intense church scene in her novel, Song of Solomon. She converted to Catholicism, earned an English degree from Howard in 1953 and a Master’s degree from Cornell University in 1955. While acting as an instructor at Howard, she married Harold Morrison, a Jamaican architect in 1958, having two sons before the union dissolved in 1964.

Morrison later started working as an editor for a textbook division of Random House, publishing such names as Angela Davis, Toni Cade Bambara, Huey Newton, Gayl Jones, Henry Dumas, and Muhammad Ali. Nittle noted Morrison saw the Black community reflected in the Old Testament and the grandeur of its language, embracing its message of anti-oppression, liberation, and empowerment. The author maintained that Morrison first used The Bluest Eye as Pecola Breedlove confronts colorism, family dysfunction, and self-hate. In fact, Morrison knew a “colored” girl from her own life, who craved blue eyes. In her debut novel, Pecola suffers a mental breakdown after her rape and pregnancy.

For Morrison fans, it was always the heady blend of spirituality and magic realism that was often the draw of her 11 novels, including Sula (1973), Song of Solomon (1977), Beloved (1987), Paradise (1997), Love (2003), A Mercy (2008), and God Help The Child (2015). These were people of faith who knew the designs of dreams, foretell the future, welcome ghosts, and influence the health of the mind, body or spirit.

Morrison explained: “Narrative is radical, creating us at the very moment it is being created… For our sakes and yours forget your name in the street; tell us what the world has been to you in the dark places and in the light… Tell us what it is to be a woman so that we may know what it is to be a man. What moves at the margin. What it is to have no home in this place. To be set adrift from the one you knew. What it is to live at the edge of towns that cannot bear your company.”

Often the concept of magic realism does not work, for like Nittle emphasized the spiritual clout of the work over the popular discussion of the practitioners of the genre such as Marquez, Cortazar, Borges, Amado, Asturias, and Carpentier. She even quoted the critic Patrick Giles comparing the overpowering influence of Catholicism in Morrison’s writing like the signature voices of Flannery O’Connor, Thomas Merton and Walker Percy. The long-time Catholic author mined themes of death, rebirth, and redemption in Song of Solomon, Beloved and Paradise, even when she lets her characters live supernaturally after death.

Nittle, ever observant and noting Morrison’s advanced age, quietly commented the author’s view that “they’re all beginning to merge into one.” In 2017, two years before her death, she concluded she got mixed up when discussing her eleven books because they all seemed the same. While all her books probed trauma, there is ample room for spiritual healing, racial pride, wisdom of the elders, and resilience which form the heart of these instructive texts.

Toni Morrison’s Spiritual Vision does not close the door on any of the truths discussed here, but rather “leaves the endings open for reinterpretation, revisitation, a little ambiguity.” Nittle discovered a literary kinship between James Baldwin, Chinua Achebe, and Morrison in that none of these sages feels pressured to please all sides. Before wildly endorsing this book, there is a quote from her Nobel speech that summed her quest: “We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.”