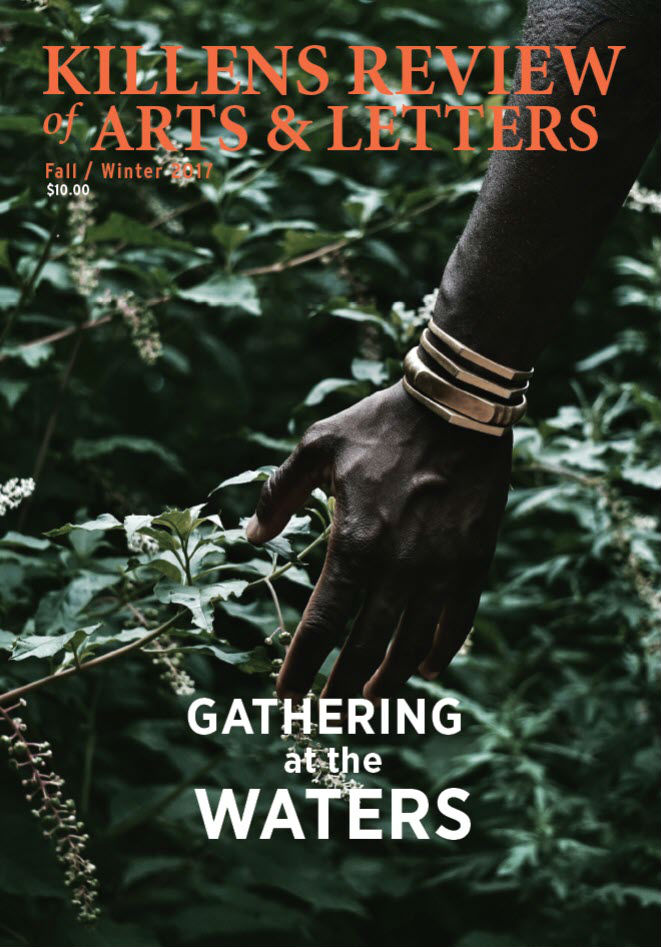

Book Excerpt – Killens Review of Arts & Letters (Fall / Winter 2017): Gathering at the Waters

Killens Review of Arts & Letters (Fall / Winter 2017): Gathering at the Waters

Edited by Clarence V. Reynolds

Fiction, Magazine

More Info ▶

Fiction Excerpt: “Lynched” by Kim-Marie Walker

When mother named me Madame Augusta Nero in 1920, she intended whites around our small-town Mississippi community to speak to me proper. “If they even ask for her by name,” she told my father, “they will surely pause before saying ‘gal’ or ‘hey, gal.’” Or later in life, ole gal or Auntie-some-made-up name of their preference.

My name never worked out the way my mother intended. In my teens, Madame got awkward, so I switched my first name to Augusta. For decades, whites called me “Gussie” or “Gussie-Gal” no matter how often I corrected them. Makes me glad the spirits of In-Between never asked for my name. They too busy butting in this world, figuring what went wrong, or passing on messages they should’ve dealt with while alive. With years of communing with the dead I know one thing sure: There are levels between heaven and hell.

Earlier today, minding my business of sipping watered-down bourbon with crushed spearmint, I met the roughest-looking In-Betweener ever, William Joseph Brock. He said to call him “Willie Joe Two” on account of his father being Willie Joe, the first.

Willie Joe Two had been shot with something powerful, at close range. His tattered, blood-stained shirt exposed the white flesh of his massive upper body but slacked off sickeningly in the space where his left arm should have been. I wasn’t used to In-Betweeners showing up all grubby during my cocktail hour. But beyond their oftentimes gruesome appearance, most had interesting stories to tell.

Essay Excerpt: “And Now… A Message from the President” by Rochelle Spencer

Imagine: Nine blocks away from folding tables selling pineapple-scented oil and coconut-infused incense, Shea butter soap, and old-school R&B records, there would have been a clinic. Nine blocks from a street where teenagers show off their verbal dexterity, where Al Green’s and Frankie Beverly’s voices drift through the air and compete for philosophical dominance (is life “love and happiness” or is it “joy and pain”?), where children’s giggles burst soap bubble-like through the air, there was a place where Black people’s pain was heard, treated, and recorded.

Located in Central Harlem between West 133rd and 134th Streets, in the basement of St. Philip’s Episcopal Church, the Lafargue Psychiatric Clinic wasn’t really a hospital, though it did attempt to solve perhaps the greatest of health problems—mental health. Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts discusses the Lafargue Psychiatric Clinic in Harlem is Nowhere and reminds us “mental health cannot be divorced from sociology and economics”; if cultural alienation thrusts us into a strange and unreal mental space, then where do we find stability? The New York Public Library’s archives reveal that “Reverend Shelton Hale Bishop…offered free use of the basement space in the parish house, where the clinic remained until its closing in 1959. The clinic was named after the nineteenth-century, Cuban-born physician, philosopher and social reformer Paul Lafargue.” Students of psychology may be familiar with the name Fredric Wertham, the social reformer; students of literature know the names Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison, and their psychological novels—all three men were involved in the structuring of the clinic. The Lafargue Clinic was said to aid its mostly African American clients by offering, what Wertham called “the will to survive in a hostile world.”

The will to survive in a hostile world. How hostile the world was then and how wrathful it continues to be. Police shootings, an unemployment rate that only deepened during and after the Great Recession, a recent study reveals Black people are the population most likely to be homeless, another finds white high school graduates have a higher median worth than Black or Hispanic college graduates. Consider these statistics, then wonder: are we crazy, or is the world?

Read Center for Black Literature’s description of Killens Review of Arts & Letters (Fall / Winter 2017): Gathering at the Waters.

Copyright © 2017 Medgar Evers College/Clarence V. Reynolds No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher or author. The format of this excerpt has been modified for presentation here.