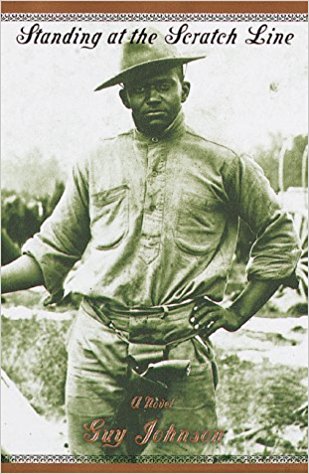

Book Excerpt – Standing at the Scratch Line

Standing at the Scratch Line

by Guy Johnson

Random House (Dec 01, 1998)Fiction, Hardcover, 548 pages

More Info ▶

LeRoi picked up the rifle that was leaning against a root with its stock in the water. He checked the barrel carefully for obstructions, then mounted the rough ladder that led up to the platform. Peering over the rim of the platform, he was surprised at what he saw. His arrow was deeply embedded in the man’s rib cage, but that is not what surprised him. It was the badge on the man’s chest. LeRoi had been expecting one of the DuMonts or their kin. Instead he found the corpse of a white man who had pale skin, greasy brown hair, and a handlebar mustache. He was obviously a deputy. As LeRoi pulled his arrow free and wiped it off on the body of the deputy, he pondered whether he and his uncle had walked into an ambush. Cupping his hands and blowing into them, he made two quick owl hoots, a signal of alarm.

His signal was answered by six or seven shots. Standing up, LeRoi could see the flash of a gun from another tree platform fifty yards away. As LeRoi shouldered the rifle and took aim, he saw the pinkness of the man’s face on the other platform. He squeezed the trigger and saw the man’s body jerk backward and fall into the sea of vapor. Several more shots were fired in the distance, but LeRoi couldn’t see where they came from.

It was clear the DuMonts had found out about the Tremains’ raid and had somehow lured the sheriff’s men out to take their side. LeRoi went through the deputy’s pockets, checking for valuables. The man had only three dollars, which he took along with the badge. At the base of the tree, he put the rifle and the bow into the small dinghy and paddled out to find how his Uncle Jake had fared. Entering the channel, he let the current carry him. He levered another bullet into the rifle’s chamber and set it against the gunwale; he knocked an arrow into his bow. Occasionally, he would row to avoid partially submerged logs and other debris, but for the most part he listened and stared into the fog.

Somewhere ahead of him to his left, a man cried out in pain. LeRoi dug his oar deep into the water to change direction and sent the dinghy slithering across the water. There was another cry, sounding like his Uncle Jake. Up ahead he saw movement around the dim outline of an island. He let the dinghy come to rest in a small thicket of bushes forty feet distant from the island. There were sounds of heated conversation.

“Get this cargo back aboard the Sea Horse while I find out how this nigger knew about our meeting.” It was a voice of authority.

Another voice responded, “Aye, aye, sir.”

A man cried out again. It was a long wail of agony and this time LeRoi knew it was his uncle.

The gruff voice spoke again. “Tell me, nigger, how did you know that we was going to be meeting here? It ain’t gon’ get no easier for you. You might as well talk now and save yourself a lot of pain.”

The other voice called out, “Billy! Billy, bring the boat in. We need to load up!”

LeRoi heard the sound of an engine start and saw a small twenty-five-foot cargo boat chug into view. It was the type of boat that small-time traders used to sell their wares along the distant reaches of the bayou. The Sea Horse passed within fifteen feet of LeRoi on its way to the island. Billy was visible as he steered the boat to its makeshift mooring. LeRoi drew back his bow and let the arrow fly.

The force of the arrow penetrating into his shoulder knocked Billy into the water with a splash. There was no other sound except the engine of the Sea Horse. The boat continued chugging toward the island.

“Billy! Billy! Back off the steam! You’re going to run aground!” The Sea Horse continued on its course. “Billy! Billy! Are you daft, man?”

“What’s going on over there?” the authoritative voice demanded.

“I don’t know, sir! He’s got way too much speed!”

LeRoi pushed off from the thicket and followed the Sea Horse, using the boat to shield his approach. Before the boat crashed into the island, he heard his uncle call out defiantly in a voice racked with pain, “Just kill me, cracker! I ain’t telling you shit!”

The Sea Horse plowed into the foliage growing at the water’s edge. LeRoi saw a man clamber aboard and pull the levers to stop the engine. Before the man could turn around, an arrow struck into the woodwork above his head. The man swiveled and jumped over the side of the boat into the water. As he splashed away he shouted out, “There’s more of ’em, sir! There’s more of ’em!”

“Jimmy Lee? Jimmy Lee?” the voice called out. “Are you alright, man?”

“I ain’t hit, but there’s more of ’em! I’m gettin’ out of here!”

“You better come back here, Jimmy Lee!”

LeRoi cursed himself silently for missing the man in the boat, but the movement of the dinghy had made his shot go wide. He paddled alongside the Sea Horse and climbed in. LeRoi took another arrow from his quiver and waited. He heard a man walk through the underbrush to the prow of the boat. LeRoi waited until he started to walk around to the side before he stood up. As soon as he reached a standing position, LeRoi saw the man swing a double-barreled shotgun in his direction. He ducked as both barrels discharged just above his head, shattering the glass windshield and splintering the wood of the navigation cabin. LeRoi stood up again, hoping to catch the man loading more shells into his shotgun, only to find him running away through the trees. Aiming carefully, he caught the fleeing figure in the thigh. The man went down but got up limping. He could be heard splashing into the water on the other side of the island. LeRoi got out of the boat cautiously and scouted the island to ensure that there were no more enemies about. He could still hear the injured man making his way noisily through the water to safety.

Uncle Jake was lying next to a smoldering fire. He was bleeding from a bullet wound to his stomach, blood oozing out with every intake of breath, covering his shirt and pants with its dark maroon stain. There were burn marks on his uncle’s face and neck. LeRoi knelt and lifted up his uncle’s head.

Jake opened his eyes slowly. “I’m gut-shot, boy. I’m gut-shot. I ain’t gon’ be making it home with you this time.”

LeRoi said nothing. His uncle was growing steadily weaker as he watched. He felt a vast void within himself.

“You got to get out of here!” his uncle whispered. “We done walked in on some gun-running business. We done killed some pirates too. They’ll be coming back here as soon as they find out what happened.”

“I think I killed a couple of sheriff deputies too,” LeRoi mumbled, unable to take his eyes off the blood pumping out of his uncle’s wound.

“Damn! Big stars fallin’; won’t be long before day,” his uncle gasped. “Help me to the boat, boy. I want to be buried with my people.”

As LeRoi carefully lifted his uncle in his arms he said, “Looks like those DuMonts tricked us into an ambush.”

“That may be true, but two of ’em paid for this trickery. They’s lying on the other side of the island. I shot them first.”

In the distance they heard a man bellowing, “Ahoy! Ahoy Barracuda! Ahoy! We’ve been attacked! Ahoy Barracuda!”

LeRoi carried his uncle to the Sea Horse. If there was any chance of his survival, he had to be gotten home quickly and only the Sea Horse could do it.

“Don’t leave them guns and ammunition,” his uncle advised as LeRoi laid him down in the Sea Horse. Sweat was streaming down Jake’s face. “We gon’ need all the guns and ammo we can get if the pirates find out we was the ones who broke up this deal.”

LeRoi made sure he could push the Sea Horse back into the water before he started loading the boxes of rifles and ammunition. The boxes containing the rifles weighed so much that he had to drag them to the boat, lift them against the gunwale, and slide them over the side. He loaded all the ammunition before he heard the sound of another steam engine chugging in the distance. Out of ten boxes of rifles and ammunition, he left three. He pushed off and clambered aboard the Sea Horse.

LeRoi was numb. He didn’t want his uncle to die. He focused his attention on getting the steam engine started. He pitched six logs into the fire to raise the boiler’s heat and waited for a head of steam. The engine stalled several times before it engaged with a slow mechanical clatter. LeRoi backed the boat out into the channel and turned the boat upriver. After fifteen minutes of steaming in midchannel, he passed the dark shape of a massive mangrove tree and turned into a small slough.

As soon as he rounded the first turn in the slough, three hundred yards from its entrance, he released the pressure in the boiler and cut the engine. Then he went to check on his uncle. Jake was unconscious and breathing shallow breaths. LeRoi attempted to make him as comfortable as possible and put a bundle of clothing under his head. He picked up a long stout pole, which all bayou boats carried, and began poling the Sea Horse slowly along. He didn’t want the noise of the steam engine to give away his position. He knew that within half a mile a larger waterway intersected and he would be able to start the steam engine again. Soon the trees overhanging the water created a dense canopy that cut the light and gave the impression of a long, winding tunnel. The fog grew progressively thinner as LeRoi pushed the Sea Horse further along the slough.

It was hard work, but LeRoi poled the boat steadily, changing sides to keep the craft in the center of the slough. He refused to quit. He felt that if he could just get his uncle home alive, perhaps there was a chance. There were other things to think about. He and his Uncle Jake had created a problem for the family because white men had been killed. If it had been only DuMonts that had been killed, there would have been no problem. No one would have even investigated their death. It was different when colored men killed whites, particularly sheriff’s men.

LeRoi did not waste a moment of sorrow for the men he killed. It was not a moral question for him; it was what he had been raised to do. His family had been feuding with the DuMonts for generations. Before he was ten years old, LeRoi had seen his father and two older brothers killed during a DuMont raid on the Tremains’ corn liquor still. It was a memory that remained close to the surface. He would have been killed as well if he had not hidden in the surrounding underbrush. From that day on, he couldn’t wait to go out and spill DuMont blood. As far as he was concerned, death was a natural consequence for those who were not careful or alert. His only concern about killing whites was the heat that it might bring down on his family.

LeRoi, large and unusually muscular for his age, took part in his first raid against the DuMonts when he was fourteen years old. During that raid he became what his uncle called “blooded” because he killed his first man. On his next raid, he was blooded again, but he was given greater respect for pulling an injured cousin to safety while under fire. The Sea Horse, rifles, and ammunition represented the booty from his fifth raid on the DuMonts and he was not yet eighteen years old.

LeRoi stopped poling and checked on his uncle, only to find that Jake was dead. He had passed away without returning to consciousness. The blood from his wound had stopped pulsing out of his body and was congealing on the deck. Jake’s face had the look of serenity. If it wasn’t for the coldness of his skin and the lack of respiratory movement, he could have been mistaken for being asleep. But he was not asleep, he was dead, and no amount of praying would bring him back.

Uncle Jake had taken him under his wing and had served as a surrogate father after LeRoi’s own father had been killed. LeRoi felt as if his heart had been ripped out of his chest. He dropped to his knees, fighting back tears, and cupped his face in his hands. It seemed that nearly everyone that he cared for was being snatched from him. It seemed like a punishment to him.

The Sea Horse scraped bottom and jerked to a halt. LeRoi slipped listlessly into the water, which was barely four feet deep, and checked for the obstruction. A log had been laid across the creek and embedded into the bank on both sides, one of the logs his family had planted to prevent large boats from using the slough. By rocking the Sea Horse up and down, he was able to jockey the boat over the log with only a few serious scrapes.

LeRoi had no words for the sadness he felt as he got back into the boat. He had only formless emotions, which brought the taste of bile into his mouth. He picked up the pole, took a deep breath, and stuck it back into the water; shoving hard, he propelled the Sea Horse on down the slough. He could not have said that he loved his uncle, for he had never used that word in relationship to himself, but he felt the agony of loss. And as with all such negative feelings for which he had no words, LeRoi had to distill them into something purer-like anger or hatred-in order to understand them. He burned with a hatred that was beyond his years. He now had a greater debt to repay the DuMonts, one he would never forget.

He remembered a story one of his Sunday-school teachers had told. It was about how when each person is born, he starts off as a blank page, and with the passing of each day, more of his life is written on the page. People died when there was no more room on the page to write. He had felt then, and he felt now, if he had ever started off as a blank page, it was no longer true. He felt like his page was already filling up with little mean words about loneliness, pain, and disappointment. There didn’t appear to be room on his page for words about happiness or joy.

Read Random House’s description of Standing at the Scratch Line.

Copyright © 1998 Penguin Random House/Guy Johnson No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher or author. The format of this excerpt has been modified for presentation here.