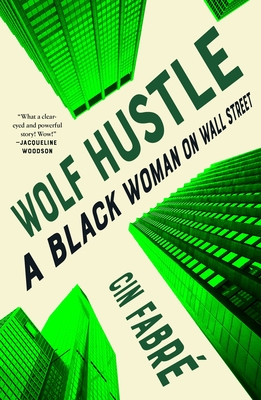

Wolf Hustle: A Black Woman on Wall Street

Excerpt

Introduction

The hustle has always been with me. Once I discovered the stock market I became infected with the delirious joy that comes from a successful speculative trade, a short, an initial public offering (IPO), all the bells and whistles that have the power to get you dirty, filthy, abominably rich (and, by the same token, the power to get you to terribly, horribly, heart-attack-inducingly lose everything). That’s when Wall Street became my hustle.

There were drugs everywhere, cocaine and quaaludes, sex, too, of course, but the drug I can still feel coursing through my veins to this day is the energy of the Pit. It was palpable the second you walked into the building—the air itself was electrified with frenetic action and the thrill of making money. Or at least, the promise of it. The shrill cacophony of phones ringing and voices calling out, the booming laughter exploding at a crude joke, the tang of anxious sweat hanging under our noses—it all coursed through me, pushed me to work harder than I ever had in my whole life. It was intoxication and agony. I took in the dysfunction, tried not to let it decay who I was as a person.

When you hear about the wolves in finance, you probably envision the Jordan Belforts of this world—and the tales of the crazy hours they worked, the antics they got into off Wall Street with their ties discarded and hair no longer neatly slicked back. Away from their significant others, out in the Hamptons or in a hotel room, bottles upon bottles of Dom, mountains of snow, thousands of dollars thrown around carelessly, sometimes crumpled up or burned just because they could. It’s all true. I was there, and I witnessed it. I took part in some of it, too. But these wolves—many of whom built (and lost) vast personal fortunes at the expense of others—were part of an exclusive club. You know the one I’m talking about—the boys’ club. Specifically, one made up of white men. I wasn’t part of that club. As a Black woman on 1990s Wall Street, I certainly wasn’t supposed to be there. I refused to accept that. Why couldn’t I have a seat at the table? If I wasn’t going to receive an invitation, I was going to keep showing up until a seat was made available for me. None of these men—some coming from humble backgrounds, most well-to-do, all equipped with the inherent privilege that comes from being a white man, a valuable currency in itself—had faced what I had. I showed up to the boardroom every day with an “I-have-nothing-to-lose” mindset that was as strong as a white man’s privilege. Disadvantages? I WAS the advantage, and I would use everything I had to achieve success.

The money, the drugs, the parties, the sharp suits, the fast-talking brokers—that’s part of the story, sure. But it’s not the whole story. As is often the case, history (and pop culture, for that matter) has gravely overlooked the voices of those who don’t check certain boxes. Nobody knows the part of the story in which a daughter of Haitian immigrants, who grew up in the Bronx projects, broke into Wall Street to become one of its youngest Black female stockbrokers, landing clients worth hundreds of millions. And frankly, that part of the story is much more interesting.

* * *

I would have found my way to the stock market one way or another—you can believe that. But my introduction to the bull and bear came from, of all people, an awkward high school student named Ali—we’ll get to him in a moment.

Eyes always on the ground looking for the gleam of a quarter or a nickel fallen from someone’s pocket onto the sidewalk, remorselessly looting cash from my dad’s hidden stash, I always burned to make money, to hoard it, save it, and spend it. You see, in lieu of outward showings of affection, my parents placed their love in things, my mother proving her love for us children by paying for our tuition, our clothes, our housing, my father demonstrating his lack of love by selfishly spending only on himself. Money was currency not only in the wider world, to buy movie tickets and Nikes and schoolbooks, but a channel through which to funnel our deepest emotions, our lusts, loves, and ambitions.

So it really can’t at all be a surprise that I was enterprising, to say the least, constantly drawing schematics in my head, planning various get-rich-quick schemes as a kid, first so that I could buy candy and shock my tastebuds with sugar and carbs, indulging in addictive pleasures like Chicco sticks, Red Hots, Boston Baked Beans, Now & Laters, and chalky bubble gum. Later, it was so I could save to buy a car, which I saw as the ultimate path to freedom, a way to escape the confines of my life, which mostly consisted at that time of yelling parents and dark bedrooms.

At thirteen, I became a tutor, assisting elementary school kids twice a week with their homework, helping them understand addition and subtraction, multiplication and division, which I’d mastered long ago to best be able to determine how much bang for my buck I could get at the corner bodega near our house. I made six dollars an hour, which was popping for 1989.

But it was a couple of years later that quiet, stocky Ali opened my eyes to the fact that there was an entire world in which men and women—mostly men—existed solely to hustle and were held accountable for making bank. I knew I could fill that role. I could do it with my eyes closed.

At that moment in time, my hustle was lunch tickets. The target? Queens Vocational Technical High School in Long Island City. If you’ve been to Long Island City recently, you might think of sleek high-rise buildings, where families and well-to-do yuppies live with their domestic partners and designer dogs, shopping at tastefully appointed Foodcellar Market or, better yet, ordering their groceries in for the doorman to receive on their behalf. Muscled, smooth-skinned young people with management titles and 401(k)s, whose sights are set on conquering Manhattan, which they can see from their twenty-fourth-story balconies. You know the type.

The Long Island City of my youth wasn’t that. Not even close. There wasn’t even a Starbucks to be found. Can you imagine? Just a beat-up coffee truck with coffee, black or with milk. Not a latte to be seen for miles.

Back in the early nineties, Long Island City was a piece of Queens that very few people had heard of—it was all abandoned factories, rusted-out cars, and cracked pavement. There was nothing glamorous about it; its gentrification wouldn’t happen until years later when developers realized they could make the waterfront area sexy and jack up the price of everything infinity-fold. I do admire their eye for opportunity. Everyone’s gotta make a buck, and they saw an opening.

Well, when I was in high school, there was a diner that all the students hung out at before first bell, there was a Mickey D’s that kids went to after school for greasy fries and McFlurrys, and there were a few nondescript bakeries, feeding out bread and other baked goods in trucks for supply elsewhere, probably in better-to-do neighborhoods. And that was about it. Not much else existed in the area, apart from my school, Queens Vocational Technical High School, and another vocational high school nearby that taught, of all things, aviation mechanics.

Queens Vo prepared you to work in blue-collar jobs across various industries. If you went there, you were likely not considering college after graduation. For many in attendance, completing high school was a feat in itself, as many dropped out because of unplanned pregnancies or to work full-time to help their families out. The areas of focus were cosmetology—mostly Black girls and Latinx girls did cosmetology; plumbing, medical assistance, computer technology, electrical installation, electronics technology, and business. Most of the guys at the school picked electrical or computer tech, and the few white girls in school and some Latinx girls did business. I also chose business because I felt that I could pick up practical skills that would help me hustle in whatever career I chose.

Apart from learning our vocation, we also had math, art, science, social studies, English, and gym class, but our vocational classes dominated our time. Which is how I came to know Ali, who was also in business. He might not otherwise have interacted with me—he was a fierce introvert—but I was curious to know more about him, particularly because he always seemed to be flush with cash. Besides, I liked quiet people—they were good listeners, and I was always running my mouth, in need of someone to offer an occasional head nod or an “oh, yeah” to accompany my verbal flow. Ali had a seriously cool car with constantly blaring speakers that had to have cost him a pretty penny. And he often participated in my lunch ticket hustle when I could pin him down.

Let me break it down for you. At Queens Vo, we didn’t have nice things. We didn’t have a gym. We always had to exercise outside, rain or shine, even in the dead of winter. We didn’t have a cafeteria, or even a real kitchen—only an auditorium, where the lunch ladies would hand out simple hot lunches, usually a microwaved cheeseburger wrapped in foil accompanied by a carton of chocolate milk. We’d take this to the auditorium and balance our lunch trays precariously on our knees while sitting on folding chairs, the cold seats biting in winter and searing our asses in summer, smacking us when we stood up if we didn’t move fast enough. Lunch tickets cost one dollar. If you were really poor, you could notify the lunch ladies that you needed assistance and you could get your lunch for free, but most kids chose not to do that, perhaps to avoid public embarrassment, and instead would fork over a buck to get lunch. I saw my in there.

If you were to ask me whether stealing is a crime, I’d have to put that right back on you. Who’s doing the stealing? Are they economically disadvantaged? Are they stealing from someone or something that has historically benefited from their labor, underpaid or not paid at all?

What I’m trying to get at is, as cliché as it sounds, there’s a lot of gray in this world and seeing things in stark black and white isn’t always the way to do it.

Or maybe I’m just trying to soften what I’m about to tell you. You be the judge.

I stole from my school and I didn’t feel a shred of guilt doing it. I took six lunch ticket books from the front office by distracting the lunch coordinator, then sliding the little stapled booklets into my backpack one day. They fit right in, as if they should have been there and were taking their rightful place nestled among my notebooks and textbooks. It was easy and felt right.

I sold these tickets right back to the kids who would have bought these same tickets from the school. Instead, they bought them from me. Why did they do that? They weren’t getting a discount—I would never sell myself short, come on—and they weren’t getting any extras, like dessert, thrown in. So why did they buy from me?

I honestly think they liked fucking over the school. I know I did.

They also may have liked the transaction as much as I did, crinkled and worn dollar bills exchanging hands in return for the little slips of paper that would buy them a burger or a sandwich or some other mediocre lunch item.

Maybe they wanted to support me—they knew and respected a hustle when they saw one. Or maybe it felt like some kind of illicit deal—it probably felt good doing something wrong.

All I know is that kids bought tickets from me every day, and my proverbial nest egg grew. Sometimes, kids even handed me their lunch tickets that they hadn’t used, which meant I’d make a couple of extra dollars a day.

I usually sold ten tickets a day, which meant ten dollars, more if students gave me their unused tickets. I’d walk the lunch line, up and down, like a trench-coated scalper hawking game tickets. I’d forfeit my own lunch ticket in order to make an extra buck (I’d often eat my friends’ leftovers that they didn’t want or I would be one of the few to claim free lunch) and it went really well for a good chunk of time.

But an eagle-eyed lunch lady had spotted me trawling the line one day and reported me to the principal, Mr. Serber. Lunch ladies were always looked down upon by the administration, and I hoped that they’d keep their mouths shut, would sympathize with me over the Man, but nope, it wasn’t meant to be.

Mr. Serber, a white, middle-aged man with a comb-over, small beady eyes, and a hawkish nose, awaited me in his cramped office. He shut the door and sat me down opposite his desk. His own chair made a sad exhale as he sat and steepled his fingertips, looking over them at me. He sighed, as if the weight of the world were on his shoulders, and then he chose not to see the budding entrepreneur in front of him.

“I have been made aware that you are selling lunch tickets, Ms. Fabré,” he said, his eyes narrowed, looking at me.

It never entered my mind to lie to him here, though I had no problem lying to adults. I simply didn’t see anything wrong with what I was doing. After all, I was charging face value—I wasn’t even hiking up the price. I confirmed to Serber with a nod of my head. He let out another weary sigh. He almost seemed disappointed that I had let the truth escape so easily, but I was a seasoned pro, from years of practice at confession having attended Catholic school before coming to Queens Vo. He took a moment to regroup, then picked up his interrogation.

“Well, how did you come into possession of these ticket books, then?”

Yikes. He must have known about the missing books.

I told him part of the truth—that friends gave me their unused tickets and I resold them. No harm, no foul.

He dropped the “F” bomb.

“Do you know that what you are doing is a felony?”

At the time, I didn’t know what the word meant, so it didn’t scare me. Looking back, I don’t exactly love that he was trying to criminalize me, a young Black girl.

I let him drone on for a few minutes about right and wrong before it felt like the torrent was reaching its end. I assured him that I wouldn’t do it again, and he let me out of his office with a stern warning. Of course, the next day I was back in business, and the day after that, I landed in the hot seat with Serber again. This time, he sighed and theatrically rubbed his face.

“Ms. Fabré, are you still selling lunch tickets?”

I gave him the wide-eyed stare that I sometimes used to disarm adults, and vehemently told him I wasn’t, that kids were continuing to come to me looking for tickets, and that I was turning them away as quickly as I could. You could practically see the halo hanging over my head in that moment.

Serber delivered a righteous speech, then shooed me away with another warning. Like any good businessperson faced with a challenge, I pivoted, selling tickets outside of the auditorium, away from the prying eyes of those cawing lunch lady crows.

I was a charismatic seller, offering those reluctant to buy from me promotional freebies with no supposed catch. Of course, there was a catch; the catch was that I then guilted them into purchasing tickets from me, obligating them to be customers.

One afternoon, I spotted Ali, an easy target when I could manage to get to him, as he usually had cash and could be persuaded to part with it without too much difficulty on my part. Ali was a weird guy with weird mannerisms—he was so soft-spoken that you always had to lean in to hear whatever it was he was saying. He was painfully tall and sported a mustache, which was an impressive thing to be able to grow successfully in high school, but which also meant that he stuck out like a sore, or rather hairy, thumb. Plus, the mustache made it impossible to read his lips, so most kids had a hard time communicating with him. He never started conversations with anyone, and he had very few friends. When he did choose to say something, he always looked nervous, his eyes darting around, as if he was worried he was about to be overheard giving away classified information. I half-suspected that Ali was an undercover cop, an adult gathering secrets about the student body like in 21 Jump Street. All that said, Ali was ahead of his time and very mature. I knew if he opened his mouth, it would be to say something that I should listen to.

Our school was tiny—my graduating class had only about two hundred people—so I made it my duty to get to know everyone. Ali tolerated my presence because I wouldn’t allow anything else—I would force conversation upon him and he would generally oblige with some short, soft-spoken remark.

That day, as I was making my rounds, I saw Ali towering over everyone else, waiting for lunch. This was a rare opportunity, as he usually ate greasy-spoon food at the diner around the corner from the school. I wanted to see what information I could mine from him, so I couldn’t pass him up. I made a beeline toward him.

As I locked eyes with Ali, I saw a wary look pass over his face. He knew all about my hustle, and had paid for tickets, I suspected, just to get rid of me. I didn’t mind—as long as he bought from me, I didn’t care what his reason was. He cut me off before I could begin my spiel in earnest.

“You have change for a five? ’Cause I know you’re gonna ask me to buy a ticket,” he said softly.

I grinned. A fellow business person, getting right down to brass tacks. I liked it! I made change and we exchanged money for the lunch ticket.

Coolly appraising him, I asked, “Ali, how could you afford to buy your car and those stereo speakers?” For that level of profit, I couldn’t think of much else that would be possible for kids in our world other than selling weed, or maybe working a part-time job for years.

Ali explained that he’d been speculating in the stock market and had made a tidy profit recently. He decided to treat himself with the stereo upgrade.

I looked at him blankly.

“What’s a stock market?” I’d never heard of it, was suspicious of it, wanted to learn everything I could to see if I could take advantage of it for myself.

Ali was incredulous—he couldn’t believe that I’d never heard of the stock market, that I was completely unfamiliar with terms like the Dow and Wall Street and NASDAQ. It was all foreign to me—until that point, I just wanted to be able to buy enough candy so I could get a sugar high and not fall asleep in English class.

That day, Ali gave me a crash course on the stock market, explaining about buying and selling, holding and shorting, stocks and bonds. He shared that he held a joint account with his dad and, with the guidance of an investment adviser, had a profitable portfolio.

I was instantly hooked—I could feel the irresistible pull of the market even when filtered secondhand through Ali. This sounded like a far better way to make money than selling drugs or working long hours at some menial labor job. Ali parted ways with me by telling me that the more money I invested in the market, the bigger the return would be. He conveniently forgot to mention the other side of the coin: losses.

But the few hundred dollars I’d saved from my lunch ticket business weren’t enough to put into the market if I wanted a considerable return. And my parents certainly wouldn’t be giving me any money to invest—my mother didn’t trust banks and hid all her savings in various places around the house, while my father had never handed out more than a quarter to any of his children (he didn’t have a favorite among us—he was his own favorite, of course).

From that day, I vowed to find a way into the stock market. For now, all I could do was continue to hustle, so I put all my energy back into my lunch ticket biz.

My “regulars” had it good—I was a generous salesperson, offering credit if they were short on some days. They’d often run up tabs, then pay me in lump sums later. I ran a neat ledger in my head and kept track carefully of who owed me what. I knew who was good for it, and I didn’t often make judgment errors, choosing to work with those who I knew would cough up cash when I asked for it.

But there’s always going to be someone who tries to take advantage of your generosity, who will lean on you until you’re forced to teach them a lesson and show them who’s boss.

Alicia was that person for me. Also in the eleventh grade, she was so pale that you could see the blueish-purple of her veins underneath her skin.

She owed me a whopping twelve dollars and had started dodging me when she saw me. But I knew she wasn’t cash poor—she was buying soda and pretzels from the snack lady who sold us all sugar-loaded snacks. I couldn’t let word get out that I was soft on clients. I wouldn’t let her make a fool out of me.

So I confronted her before science class while she was gossiping with a friend at her locker. It was truly a cinematic moment as I puffed myself up and asked, “Hey, Alicia, where’s my money?”

She looked at me and rolled her eyes before continuing her conversation.

I couldn’t have that. That kind of attitude after I’d shown her such kindness and let her run up her tab to an exorbitant twelve dollars? This was disrespectful and I could not, for the sake of my business, tolerate it.

I leaned between her and her friend, forcing them to halt their conversation. “Excuse me—I asked you a question,” I said to her in a soft, dangerous tone.

Alicia was annoyed—but not as annoyed as I was. “Why are you bothering me, Cin? I told you I’ll give it to you when I have it.”

What I did next surprised even me. I grabbed Alicia by her neck and threw her against the wall, hard. I stared into her eyes, which were now clouded with fear, and I stood up straight.

“I want my fucking money,” I told her, my face inches away from hers.

I was still squeezing her neck, so she only offered a small, short nod in response. Her feet dangled, as I had lifted her off the ground with my throw. I wouldn’t have been surprised if she had pissed her pants at this point.

I released her suddenly and she crumpled to the ground before jumping up and running off, her friend already long gone.

Where did that come from? I’d always been a peaceful person and rarely engaged in fights throughout elementary school and junior high, even though there’d been plenty of opportunities. The only times I’d fought were against bullies when they provoked me: once I threw a chair at a kid’s head, the other time I grabbed a bat to swing at a kid who was taunting me but was nabbed by a teacher before I could inflict any damage. Was I turning into my father? He’d always been physically and verbally abusive to our family and I had loathed him for it. I didn’t want to be anything like him—he was a monster. But this experience felt strangely empowering to me. Clearly, doing nothing about Alicia’s debt yielded no results, but the threat of an ass whupping sure gave me what I wanted, and quick.

The next day, Alicia didn’t come to school. But she returned the following day and paid me back without further protest. She averted her eyes, refusing to look at me, and quickly handed me two fives and two singles, which were sweaty from her tight grip, before she murmured something about how she had to go. She beat a quick retreat before I could say anything to her. But she actually continued to buy lunch tickets from me, which I allowed her to do, as her debt was erased, and I didn’t see anything wrong in accepting her money (though I never extended her credit like I had before. I had learned a wise lesson here).

This moment with Alicia had given me an undeniable, electric thrill, but I was also, at the same time, horrified by it. What did it mean to snap like that and feel such little guilt toward Alicia? Was I going to turn out like my dad? Did the fact that I was worrying about this signal that I couldn’t be like him? After all, he relished his monstrousness, delighted in it, and had only become worse as the years ticked by. In the coming decade when I was on Wall Street, not sure if I liked who I had become, I would return to this moment again and again, slamming Alicia into the wall, remembering the vein in her neck pulsing rapidly against my palm while I held her by the throat.

Who was I? Who did I want to be? Who could I become?

Read Henry Holt & Company’s description of Wolf Hustle: A Black Woman on Wall Street .

Copyright © 2022 Macmillan Publishers/Cin Fabré. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher or author.