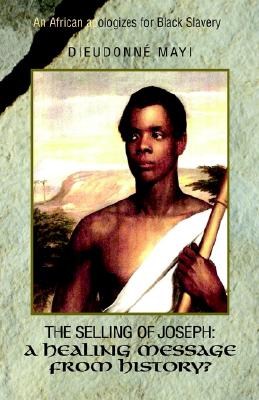

Book Excerpt – The Selling of Joseph

The Selling of Joseph

by Dieudonne Mayi

Publication Date: Feb 01, 2004

List Price: $22.99

Format: Paperback, 352 pages

Classification: Fiction

ISBN13: 9781413439144

Imprint: Xlibris

Publisher: Author Solutions

Parent Company: Najafi Companies

Read a Description of The Selling of Joseph

Copyright © 2004 Author Solutions/Dieudonne Mayi No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher or author. The format of this excerpt has been modified for presentation here.

Dedication

To African slaves in the Americas, Caribbean, and Europe, the silent and unknown black slave…

Your treatment was so inhumane, but your pain and suffering were not in vain. Do you find in my words the voice of an African asking your forgiveness for my ancestors’continental Africans’who sold you to slavery? Could you find in my words praise for the triumph of your human spirit and your achievements, a celebration of hope for you and your descendants as a people? You are my ancestors, you are my heroes.

Introduction

History is like a hidden treasure, the more you dig, and the more you are likely to discover its hidden secrets.

The inspiration to write this book came to me in February of 1999. I had just started a new job as a software engineer in downtown Seattle, Washington, USA. The excitement of the new job came at a price: a thirty-minute commute from Bellevue where I lived and had worked previously. A thirty-minute bus ride each way and inevitable peak-hour delays worried me greatly. It was a new challenge to overcome because I don’t have a lot of patience for long commutes by bus, and besides I was accustomed to the comfort of my own car.

As I sat on the bus the first day, my mind worked feverishly to invent an activity that would help me survive my daily bus commutes. Sleeping my way through was given serious consideration, but I would be bored too quickly. Talking to people on the bus? Yeah! But I had not yet made friends in this ship and besides, I am not a talkative person by nature! Reading a book came stronger as the serious alternative. However, one question remained to be answered: What book would hook me up so much that I would read it avidly each morning and evening on my way to and from work? I did not have to think long. I chose to read the Bible from one end to the other and … between the lines. I convinced myself that it would be an exciting undertaking, something of a lifetime achievement for the half-devoted Christian I am. I had read the Bible many times before, usually short passages at a time but never the whole book chapter by chapter.

I started my journey in the book of Genesis. The more I read each day, the more I developed the taste to read some more. I found the Old Testament book particularly captivating. The chapter on Adam and Eve was quite familiar and did not arouse much curiosity in me. I was more interested in how the ancient people lived, trying to picture myself in their daily lives, environment, and belief systems. I read the book in a broader historical perspective trying as much as possible not to limit my imagination to strict religious interpretations. Armed with my pencil, I read between the lines, underlining as many passages as possible and scribbling comments in the book. I confess to you, my reader, that I am quite a slow reader when I don’t scribble down notes and comments in the book as I am reading; as a result I never sell my books or seldom do so. Very often, I kindly make a verbal disclaimer to anyone who attempts to borrow my books. ’I warn you that I have written comments all over the place, hope you will live with that!’

Quite a few people around noticed my devotion after a few days. Some, particularly older people, glanced at me with admiration while the younger people (mostly professionals and students) gave me a look that did not hide the message ’Don’t come any closer, you religious zealot!’ However, I did not feel intimidated by commuters around me and I drowned myself deeper in the book.

One morning, I reached the story of Joseph (Jacob’s second youngest son), a young man who was sold to slavery by his jealous brothers (The Holy Bible, Book of Genesis, chapter 30-50). I had heard this story before at countless church services and even watched a Hollywood movie based on it. This time, however, the experience was different. I was reading the story myself, between the lines, and in the confinement of this metropolitan bus. I soon came across the place in the story where his brothers sell young Joseph to slavery. The scene became so vivid in my imagination as if the tragedy was being re-enacted in front of me. I felt between these lines something that I had never experienced before, a sensation that I cannot put in words. A beam of heat was emanating from the book and hitting my face. A secret message was coming out of the ancient scriptures and being beamed to me alone amidst this group of morning commuters.

I thought about the slavery of black Africans in the Americas but I could not draw a simple parallel with the story of Joseph; it was more than that. This was a silent message coming to me from the ancient world. It was not a message of anger or blame; it was, rather, a message of peace and hope. I came home that evening and shared the experience with my dear wife telling her that I had uncovered a hidden message in the Bible. She smiled at me as usual but showed interest and admiration.

This book is all about recognition of responsibility in the historical injustice of black slavery and coming forward to ask forgiveness for it. The story of the selling of Joseph to slavery (as reported in the Christian Bible) served only to provide me with themes that can be used to look at a similar historical injustice which occurred in the modern era of human history (1500 A.D-1850 A.D), that is, the selling of black Africans to slavery in the Americas. I am not a full believer in any views that history repeats itself; in fact I find any such views quite pessimistic. However, I wholeheartedly agree with views which see human history as a giant book of lessons, painful ones but also uplifting ones. We can learn from past experiences (or inspire ourselves from their occurrences in history) to shape a better today and positively impact tomorrow.

I would like to bring to the reader’s attention that my intention was not to write a history book about the Transatlantic Slave Trade, the ancient history of the Jewish people or that of Egypt. This would be a very vast topic beyond the intended scope of this book, and besides, there is a vast literature out there which can be of utility for the reader to explore.

Furthermore, in the endeavor of writing this book, I was not faithful to any particular perspective, moral, philosophical, religious, or historical. Hence, the motivation for writing The Selling of Joseph: A Healing Message from History was neither to re-open a moralistic or historical debate about the slavery of black Africans in the Americas, to debate on the biblical significance of Joseph’s story, nor to present any inclination toward the Christian faith. Rather, I am trying to extract from this tragedy something that has not been addressed much before: a healing message of hope for forgiveness. Samuel Sewall first used the title ’The Selling of Joseph’ (Sewall 1700) in an anti-slavery publication in which he exposed the immorality of slavery and refuted all alleged biblical justifications of the practice. Going from the premises that slavery of any human being is immoral, reprehensible, and should be condemned, I am arguing that the story of the selling of Joseph can provide a healing message from a rather tragic act of selfishness, injustice, and inhumanity. In the case of black slavery, this message calls for sincere admission of wrongdoing and for forgiveness on the part of the transgressors. This message is also one of hope, the due recognition of the accomplishments of black slaves and their descendants (African-Americans and others) in the Americas, the Caribbean, Europe, and Africa. In the remainder of the book, I am trying as best as possible not to address African-Americans and other people of African descent of the Americas as ’descendants of black slaves.’ I am aware that an increasing number (if not the majority) of these people no longer tolerate that their ancestry be defined by the painful and violent experience of slavery. However, for lack of better construct, I will be sometimes forced to use phrases like ’former black slaves and their descendants.’ I am asking you, my reader, to forgive me for that.

As individuals, we should not be held responsible for what our ancestors and forebears did. However, as a people or a society we are definitely responsible, at least to recognize the guilt of our forebears and ask forgiveness for wrongdoings and injustices they perpetrated to other groups. In The Guilt of Nations, Elazar Barkan admits that new generations can be held accountable for injustices committed by older generations if particularly the consequences of these historical injustices still affect the descendants of the victims (Barkan 2000). It is here that I am making a moral call that some of us who are continental Africans (this author being one) must recognize that our ancestors fully participated in the selling of our own black people to the Europeans. We must ask forgiveness to our brothers and sisters, the former slaves and their descendants in the Americas, the Caribbean, and Europe.

At the core, The Selling of Joseph: A Healing Message from History has a main message, that is, the recognition of the undeniable fact that continental Africans played a key role in the capturing and selling of their fellow Africans to European slave merchants for profit. Equally undeniable is the shared truth that the Transatlantic Slave Trade was and is still one of history’s most tragic and cruelest cases of man’s inhumanity to fellow human beings on a massive scale. This book pleads for forgiveness from those we wronged so much. I am warning the reader not to see in the preceding statement any intention to put Africans and Europeans on the same moral camp as it pertains to the Transatlantic Slave Trade, particularly its early motives and developments. I would like also to stress the point that not all African people or groups from the four corners of the continent engaged in the slave trade or were directly affected by it. However, historical records and evidence indicate that a significant number of groups, kingdoms, and chiefdoms on the west coast of Africa’from the current territory of Angola to Senegal’took part in the trade.

Recognition of the guilt of continental Africans as a people does not exculpate the Europeans and North Americans who engineered the inhumane trade in the first place, profiteered from it, and played a preponderant role in its development and expansion. They bear their own responsibility. Furthermore, the message of this book should not be taken as an alibi against restitution claims by descendants of black slaves who still bear the burden of the legacy of slavery. In The Guilt of Nations, Elazar Barkan has examined cases of restitutions worldwide since the end of WWII, including Jewish Holocaust victims against Germany (1950s onward) and Switzerland (1990s), the case of Korean sex slaves against Japan, Japanese-American restitutions for WWII deportations in the United States, Native Americans against the United States for loss of ancestral land and extermination, and African-Americans against the United States for slavery (1990s onward). Barkan finds that the rising movement to seek reparations for slavery has been particularly polemical so far, has received less attention outside the black community and more resistance by the United States government, white America, and some segments of the black population. In addition, he finds that the discourse has not yet gathered enough momentum to promote a negotiated political process between the victims (black slaves and their descendants) and the perpetrators (white slave owners and their descendants as well as the United States federal government which allowed slavery to be practiced in the land from 1619 until the civil war in 1861). However, Barkan agrees that restitution for the historical injustice of slavery stands (1) on moral grounds that black slaves suffered as a consequence of slavery, and (2) their descendants are still suffering the consequences of the historical injustice of slavery (continued discrimination, poverty, and racism) in the United States.

To echo the words of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., justice is indivisible, and I strongly believe that justice to those who were wronged, exploited, and denied their basic humanity is undeniable. I am introducing here a concept of moral reparations as key to healing deeply rooted historical injustices such as black slavery. In a general sense (individual or collective level), I am defining moral reparation as a two-way process: recognition of wrongdoing for an injustice done to someone else, followed by a request for forgiveness addressed to the victim. At a collective level, moral reparations require a widespread public recognition of wrongdoing for an injustice that was committed against a group; this is followed by repentance with public display of atonement (e.g., monuments, memorials, and alike) beyond mere verbal apologies by elected officials. In the case of black slavery, moral reparations are the widespread public recognition of wrong for slavery, repentance, and philo-African American1 attitudes in official policies. In my opinion, this is a first step to take for true and everlasting healing for historical injustices like black slavery, which opposes groups and races, not merely one group of people and a government. Moral reparations will help the reconnection of both transgressors and victims to enlarge the future of both races. Though, I touched on moral reparations, the focus of this book is not about restitutions or reparations; rather it is about recognition of guilt for black slavery and request for forgiveness.

It is my humble prayer that this message will find an attentive ear from the many people of African descent in the Americas, the Caribbean, and Europe. It is a plea to all of you to forgive us’continental Africans’for the gratuitous and greed-rooted inhumanity of our ancestors toward your ancestors’all of them black Africans, ironically. I equally plead to my brothers and sisters, the people of Africa, to accept foremostly that the thrust of my endeavor is rooted not in arrogance or the vanity of any claim of intellect but in the humility that I have developed as a result of my own spiritual encounter with this painful chapter of our history (which has undoubtedly affected the black race as a whole) and an attempt to educate myself to grasp its enormity. I cannot end without asking the people of European descent to lend an ear to my plea. It is not condemnation of your forbearers’ actions that motivated me to write, but rather the morally superior mechanism of recognition-forgiveness that would definitely favor a better future for race relations between the blacks and whites. For this end, accept the offer of my humble exhortation not to shy away in fear of guilt but to ride the high wings of recognition-forgiveness that definitely guarantee a better future of brotherhood and sisterhood of our two races.

It is my hope that the reader will not limit himself or herself to using the lenses of religion as the origin of Joseph’s story so often compels many to do. I also encourage the reader to look at this issue from the perspective of human beings as whole, instead of being locked in the racial (black/white) framework of mind, which has characterized a lot of debates of this nature. Further and more compelling is the need for the reader to look at this issue from the perspective of the victims: the black slaves who were treated without dignity and their descendants who inherited the daunting legacy of slavery and all its ills.

As stated earlier, the motivation to write this book is a message of peace and hope, not one of condemnation. Hence, I ask the reader to forgive me should my statements err in a condemnation of any kind, which is not intended to call upon the conscience of all parties involved to account for a moral step toward justice and brotherhood/sisterhood of the human race. The focus on those who were so unjustly treated by fellow humans is what, in my opinion, calls our conscience. That call, that shared humanity, makes us all appreciate love, each other, feel sorrow for fellow humans, and feel remorse for blatant injustice and gratuitous harm done to others. Many accounts by black slaves of their ordeal during slavery touched me to the core, but perhaps none had an impact on me more than the story of Harriett Jacobs (Gates 1987, The Classic Slave Narratives, ’Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl’) and the following words by Sarah Douglass (Mellon 1988) which still draw tears to my eyes whenever I read them. These words reveal the humanity that we all share. They also show that injustice does not just hurt the victim but also the victimizer. Finally, these words reinforce the undeniable fact that compassion, recognition of guilt, and demand for forgiveness liberate both the oppressed and the oppressor.

The last whipping

Old Mis’ give me she tied me to a tree and’oh, my Lord!’she whipped me that day.

That was the wors’ whipping I ever got in my life. I cried and bucked and

hollered, until I couldn’t. I give up for dead, and she wouldn’t stop. I stop

crying and said to her. ’Old Mis’, if I were you and you were me, I wouldn’t

beat you this way.’ That struck Old Mis’s heart, and she let me go, and she did

not have the heart to beat me anymore.

’Sarah Douglass (Mellon 1988, p. 244).

Finally, The Selling of Joseph: A Healing Message from History opens up on the whole issue of responsibility and forgiveness

The journey to reconciliation and true forgiveness starts with an admission of guilt, for true healing that comes from forgiveness cannot occur without recognition of guilt. Like faith, recognition of guilt can be preached to an individual or a group but it only happens when the soul meets itself and comes to grips with understanding its own guilt and admitting it. This process guarantees longer-lasting satisfaction with self and others, particularly those who have been wronged.

Many deeply rooted conflicts between individuals, groups, societies, and races worldwide could have been laid to rest had the parties involved admitted their own guilt and asked for genuine forgiveness to those wronged. I have always asked myself the following question, which I challenge the reader to reflect upon. What is easier: (1) to recognize one’s guilt and ask forgiveness from those we have hurt and wronged, or (2) to hide behind pride, denial, plain ignorance, or other excuses? It seems to me that the second alternative has been the unfortunate but our best choice as individuals, nations, races, and groups of people. Centuries-long hatred and resentments have resulted, which have been consciously or unconsciously passed by one generation to the next and have plagued human relations worldwide. It is my strong conviction that humility’the humility to admit one’s injustice to fellow human beings and to ask for forgiveness, call it moral reparation’is a starting footstep in this long journey into a brighter future for human relations on planet Earth.

In the first chapter, ’The Story of Joseph Revisited’, the book starts with the biblical story of Joseph as a stepping stone. From this story, I am drawing themes that will be later used as lenses to look at the painful chapter of the transatlantic slave trade and the slavery of black Africans in the Americas.

The second chapter, ’The Slavery of Africans in the Americas’, revisits the historical record of the transatlantic slave trade from its beginnings in the fifteenth century to its abolition in the mid-nineteen century. The main goal sought in this chapter is to provide the reader with just enough background for the rest of the discussion in this book. Therefore, I won’t delve into a lot of historical details. Should the reader want to know more about the transatlantic slave trade, I recommend looking at a vast literature already available on this subject.

The third chapter, ’The Day I Was Kidnapped from Africa’, is the story of a twelve-year-old African child named Mb’ngo who is captured and sold to slavery; he describes his journey from the wilderness of Africa to the slave port, then to the Americas. Being from Africa myself, I stretched my imagination to see through the eyes of an African child how this experience could have looked like. I felt that this story could provide an insight into one leg of the painful journey to slavery in the Americas, which is poorly recorded in history books. That is, the journey from the points of capture in the African interior to slave ports on the Atlantic coast. I contend that, in contrary to the Middle Passage (Atlantic leg of the journey to slavery, from the African slave ports to the Americas) which is well recorded in history, the continental leg of the journey to slavery and the ordeal that black slaves endured on that trip have not been exposed as much in classic history books.

The fourth chapter, ’If Africans Are Not Guilty of Black Slavery, Then Who Is?’ discusses the responsibility of continental Africans in the historical crime that was the transatlantic slave trade. In this chapter, I surveyed Africans living in various countries of Africa to probe their opinions about the topic. My findings seem to indicate that in majority contemporary Africans acknowledge that their ancestors shared a responsibility in the transatlantic slave trade.

The next chapter, ’The African-American Experience: A Testament of Great Achievement as a People’, discusses the accomplishments of the people of African descent who, like Joseph were sold by their own brothers to slavery. Like the story of Joseph, this chapter is bringing out some aspects of these accomplishments that most of us do not hear much about in history. The aspects that I explored are: (1) the fact that black slaves remained human, lived through slavery to see freedom, and their descendants form a well distinguishable people in the western hemisphere; (2) they contributed to the building of an economic foundation in the western hemisphere, what credit they have been historically denied; (3) in the case of African-Americans, their cornerstone contributions to the institution of civil rights for all in the United States of America; (4) their numerous contributions to Africa, the land of their ancestry.

In the last chapter,

’The Significance of Their Sacrifice: Hope’, the book concludes with a synthesis

of both the biblical story of Joseph and the slavery of Africans in the

Americas. Here I am discussing the central theme of moral reparation due

to former black slaves and their descendants. I am seeing moral reparations as a

first step in enlarging the future of all who were or continue to be affected by

the crime against humanity that was the transatlantic slave trade, particularly

the victims. Most importantly, I am arguing that such a step is necessary from

descendants of perpetrators to bring some sense of closure for descendants of

the victims who continue to suffer from the legacy of slavery; moral reparations

would definitely bring a lasting forgiveness and hope for a better future of

race relations.