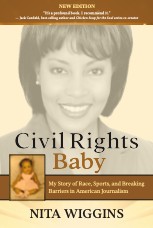

Book Excerpt – Civil Rights Baby: My Story of Race, Sports, and Breaking Barriers in American Journalism

Civil Rights Baby: My Story of Race, Sports, and Breaking Barriers in American Journalism

by Nita Wiggins

Nita Wiggins (Oct 12, 2021)

Nonfiction, Paperback, 336 pages

More Info ▶

Chapter 7: Why Did Rosa Parks Hug Me?

In my next job, at WTVM-TV in Columbus, Georgia, I landed a position that came with a prestigious title: bureau chief/assignment editor in a one-person news department. That gave me the freedom to decide the stories I wanted to report and to conduct myself in any way that I chose while in the field. To do my job, I traveled my territory along the Alabama-Georgia border in a fourwheel-drive car that I was free to take home with me. I shared a tiny office with a good-natured and respectful white colleague named Gerry Potter. As the station’s sales rep, Gerry sold airtime to clients in the east Alabama region. He treated me as an equal in every one of our exchanges during our fifteen months as colleagues in the Opelika, Alabama, office.

In this role as a one-woman band, the assignment of my life fell into my hands. The newsmaker at the center of the assignment left not only a lasting change upon my spirit but a lingering question in my mind, even decades later.

Why did Rosa Parks hug me longer than I hugged her?

I met world-history icon Rosa Parks on February 4, 1988, at her seventy-fifth birthday celebration given by the city of her birth, Tuskegee, Alabama, and its mayor, Johnny Ford. On that memorable day, I had been a TV news reporter less than two years and was enjoying my new status as WTVM Channel 9’s bureau chief.

Though a cub reporter, I took pride in being professional, polished, prepared. I had covered Alabama state politics in the capitol building in Montgomery, and everyday politics on the streets of Opelika and Auburn and in five nearby counties. Despite being young, I thought I presented the air of a veteran.

Before the event began, I spied Mrs. Parks, who was standing alone. I wondered how that could be! How could the woman to whom the event was dedicated be waiting in silence when, all around her, men and women in business clothes and teenagers in school uniforms buzzed with activity?

I walked toward her.

As I did, I recalled the pictures of Rosa Parks I had seen in school books. Crisp black-andwhite images of a prim, light-skinned African American woman with dark, silky hair pulled back from her face. Her tranquil yet determined expression preserved in her Montgomery, Alabama, police mugshot—with the inmate number 7053. On December 1, 1955, she had refused to obey a bus driver’s direct order that she give up her seat, triggering her arrest by Montgomery police. The city’s black population responded with an overt, business-crippling bus boycott.

At the same time, in a significant but largely unheralded chapter in history, four other black women filed a lawsuit against the bus company. During the year that commuters stayed off the bus, 1 the four plaintiffs scored a landmark Supreme Court victory that changed public transportation nationwide. The court’s decision in favor of Aurelia Browder and the others ended the legal segregation that white operators had lorded over riders of the buses. The brain trust of the boycott called off the economic protest on December 20, 1956. From that date forward, as Dr. King expresses in comments made at Holt Street Baptist Church, fifty thousand black people in Montgomery, and sixteen million black people in the U.S., were free to sit wherever they chose on public transportation.

Mrs. Parks was not a part of that anti-discrimination lawsuit. However, she became the public face of the organized rebellion and the spark, most people believe, that ignited the blaze. And now, I was moving toward her. I need her to remember me! my inner voice shouted.

I reached her and realized we stood at nearly identical heights. I was five-foot-three, so she must have been, too, at that stage of her life. Her signature dark hair was mostly gray and pulled into an updated French twist—still neatly pinned in place. Modified cat-eye glasses with light-pink frames had replaced the wire frames on historical record. Her lilac-colored rain slicker and babyblue flapper’s hat beautifully set off her honey-colored skin. Her clothing choices, and the overall vision of her, stirred a familiarity in me—as if my paternal grandmother were present.

Mrs. Parks was the focus of my report that day because she had helped upend the daily racebased indignations and the inequality of the world into which she, and both of my grandmothers, were born.

She was no ordinary woman! And here she was, beside me, within arm’s length, full-color and in the flesh.

I’m standing here with Mrs. Parks! the voice inside of me shouted. My mind raced to find something enduring to say. How could I leave an impression on a woman who had done so much?

I formally extended my hand to shake hers. It was what I always did with the white males I interviewed in government and business. I stated my first and last names clearly. I wanted her to truly hear them. I was determined to maintain a professional decorum.

Then something changed.

Her eyes had settled on me as she listened to my name. I looked beyond the frames of her glasses, gently meeting her gaze. These eyes, the eyes of Rosa Parks, have seen so many changes, I thought. In that moment, I became aware of how petite and thin her body was; in her lifetime of activism, she had endured so much. Death threats, insomnia, ulcers, and extended financial stress had ravaged her life and the lives of her loved ones.

I suddenly knew, in that instant, that I needed to pay something back to her. There was no death-defying sacrifice I could make for her in that moment. Nothing I could give to repay her for what she had done for black people and for society beyond the American borders. Nothing—except myself. My physical self.

I shed my professional demeanor as if I were slipping out of clothing and said, “Excuse me, Mrs. Parks—I never do this—but is it OK for me to hug you?”

Without hesitation, she replied, “Sure, baby,” and sounded just like my beloved maternal grandmother.

I leaned in to embrace her, shoulder-to-shoulder, the skin of our cheeks touching. For a petite elderly woman who appeared frail, she offered a surprisingly firm hold. I returned a powerful squeeze, contracting the muscles in my forearms to pull her close to me. I closed my eyes and lost myself in the force of her arms.

For me, the world became silent.

Our hearts rested in proximity in our quiet cocoon. We breathed in slow and unhurried breaths. I can’t recount the number of seconds it lasted. But then, too soon, the quiet ended.

With my eyes still closed, I again heard street sounds and nearby conversations. Stirred from my peaceful reverie, drawn out of a state of intoxication caused by another’s maternal affection, I drifted back into awareness—and suddenly suffered a moment of embarrassment. What happened to my signature professionalism? Had I stepped over a boundary by initiating a hug with the Mother of the Civil Rights Movement? Had I intruded on her personal space? Even as I thought these things, she still held me, and I still held her. We embraced so long that I felt I should signal the release. After all, I knew her, but she did not know me. I was hugging her in gratitude, thanking her for what she had done for my life, for what she represented to the world. But I had done nothing for her—had given her no reason to embrace me. I felt I was being unfair by keeping her locked in our embrace. Do not impose on this precious woman, this treasure. I don’t have the right, I thought.

I let go first. Regretfully.

But for a second or two more, Rosa Parks continued to hold me. She hugged me longer than I hugged her, and I do not know her reason.

Nearly thirty years after that 1988 embrace, I still search for the answer. Did she see herself in me? If she had been born not in 1913, but in 1963, we might have been trendsetters together in television journalism. Was that her thought? Did she see, with all her wisdom and civildisobedience training, that my career in television journalism added a stone of triumph in a road of opportunity she had helped to pave? Was she embracing me at all, or was she holding onto what she considered to be a victorious symbol in the cause for equality?

I will never know the answer, for Rosa Louise McCauley Parks died on October 24, 2005, at the age of ninety-two.

If I had been fortunate enough to meet her a second time, as a mature journalist and a socially aware African American woman, I could have questioned her about her intense desire for worldwide human rights. She was not an accidental participant in social movements. And while she 2 appeared acquiescent, my research reveals that she believed in self-defense. She even called Malcolm X her personal hero. If I had met Mrs. Parks again, I could have mined her vast 3 experiences as an internationalist, an opponent of the war in Viet Nam, and an objector to apartheid in South Africa. Her activism knew no boundaries; her present-day impact knows no borders.

Without the steadfast push for social and economic equality by legions of self-sacrificing activists, I would not have been a television bureau chief/reporter/one-woman band at WTVM-TV in Columbus, Georgia, and in position to embrace Rosa Parks.

To this day, I carry the fleeting seconds we spent in that puissant hug. Though I will never know the real reason Rosa Parks held onto me, I do know why I asked for the embrace: I was thanking her. She had courageously offered herself on the front line in a prolonged resistance movement against legal racism. I had benefited from the way she organized to improve American institutions during what would become seventy years of activism. But even as she and I held each other, I knew that what Rosa Parks wanted from me was not a thank you but action—a continuation of her fight against injustice.

Somewhere deep inside, I felt the beginnings of resolve.

Read Nita Wiggins’s description of Civil Rights Baby: My Story of Race, Sports, and Breaking Barriers in American Journalism.

Copyright © 2021 Nita Wiggins/Nita Wiggins No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher or author. The format of this excerpt has been modified for presentation here.