Kim Taylor

African American History Matters

A master quilter looks back to the past and weaves ancestral history into textile art designs.

The ancient West African tradition of enchanted weaving and preparing Bògòlanfini (mud cloth) for protection, sharing social status, history, and other messages, made its way to America during the Transatlantic slave trade.

Debate withstanding African American lore indicated the “Quilt Code” practice dated back to the late 18th century. Enslaved quilters weaved messages for those poised to escape to gain safe passage to freedom.

Fast forward to the mid-2000s, when a watershed moment left seasoned speech-language pathologist Kim Taylor at a loss for words. Overcome with emotion Taylor seemingly resurrected the West African tradition of enchanted weaving to create her first story quilt to commemorate the occasion. Today, Taylor is also an author and illustrator of the children’s book, A Flag for Juneteenth. Taylor’s digitized story quilt tells the tale of a community of Africans enslaved on a Texas plantation who simultaneously received notice of their freedom while preparing for the central character, Huldah’s tenth birthday celebration.

Although not discussed in this sweet children’s tale, it is hard to ignore the domestic terrorism campaign waged by Texas enslavers. They used such antics as withholding information, and deception, to pogrom that befell many enslaved Africans in 1865 Texas and beyond. The war between the North and South ended, but terrorism against the former enslaved was just getting started. #Rememberyourhistory became the through line of my April 27, 2023, interview with author and illustrator Kim Taylor.

Taylor is also a Brooklyn Technical High School alum of African American Literature Book Club Founder Troy Johnson and me. Taylor and I had a chance to reminisce about the solid academic foundation we built at Brooklyn Tech – even during the 1980s Christian nationalist movement’s Moral Majority focused efforts to ban books in response to the Civil Rights, Gay rights, and women’s liberation movements that reached its apex in the 1970s.

Like clockwork, ten years after the founding of the Black Lives Matter network, book banning is again underway – but this time, PEN America (a free expression advocacy organization) reports more than 50 groups, some with connections to larger Christian nationalist organizations are working across the U.S. to ban books that confront family violence or feature topics effecting the LGBTQIA+ community, Women’s rights, and African Americans.

The following Q&A is condensed and heavily edited for flow and clarity. We continued our chat about current events, symbolism, and how art can be a powerful tool for social and political change.

Mel Hopkins: It’s almost like you’ve come at the right time to tell a story, so antagonists won’t erase our history. You’ve told the story in a way where it’s up for interpretation – one for anybody who looks at it – it touches them differently.

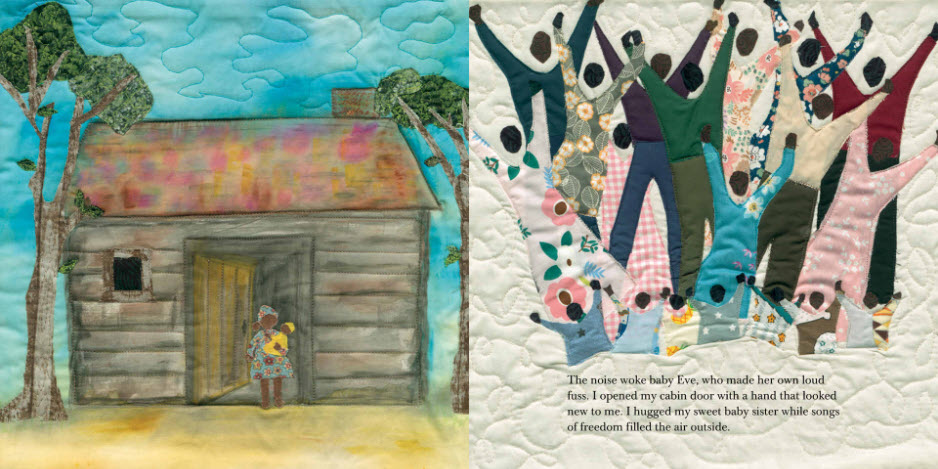

Kim Taylor: Interestingly, the book has only been out since January 3 [2023]. So, many different people, people of color and not, talk to me after I read. So many times, people who are not of color come to me saying they were so moved they were in tears with the book. So, I first found that disarming, like, “What? Wow.” What I am recognizing is that somehow the way I wrote the book does not make people feel threatened. It makes them feel empathetic. And that’s what I set out to do. My characters have no faces because I want people to see themselves in my characters and empathize with them.

MH: With the book-banning attempts going on right now, how did you set yourself apart from not having African American history hidden?

KT: Someone sent me a picture that epitomizes my feelings about that. I hate it, of course. But early on, a picture showed up on Twitter [taken in a] bookstore in an airport in Chicago. [On the bookshelves] There were other important African American Literatures. My book was on the top shelf, and the caption was, “When they try to erase and take away your heritage, they try to ban your books – Learn, learn your history by spite. Learn it anyway. My book was there with other people’s; so, it was like, wow, they’re telling us to learn your book, author, learn your history.

MH: Talk about hidden history. As a native New Yorker, I learned of Juneteenth through social media. How did you connect to Juneteenth? What was the thing that made you say I want to make this statement?

KT: Like you, I had never heard of Juneteenth. The first time I heard of it, a friend asked me to go to a Juneteenth celebration at her church. She went to a unitarian church at the time. They had an African American pastor, a beautiful Jamaican woman, and the congregation, I guess, knew about the observance because it wasn’t their first celebration of Juneteenth. I said, “Sure, I would love to go.” I didn’t know anything about it, but she said it was going to be great, and it was. [There was] Soul food, spoken word, singers, and all kinds of amazing things. And I totally rejoiced in it and had so much fun. But then, when I got in my car to go home, I was really angry because I said, “Why don’t I know about this?” Why wasn’t it taught to me?” How come it’s not in the school curriculum? I was really upset. That was in 2014, and what I decided to do to express my emotions, I made this really big quilt. I made a big story quilt with just two people, like the last scene in the book (A Flag for Juneteenth) — two people holding their baby up to the night sky.

At that time, when I made my quilt, I didn’t have Huldah in mind yet. So, It was just the parents holding the baby. Then when I started to show it around at festivals and a couple of schools, nobody knew about Juneteenth. And I was like, let me write a little story about it that I can read while I show this quilt. It was a very basic story, similar to the book, but not fleshed out so completely. People started to tell me, “You know, you should have that published. It’s such a great story.” And I was like, “You know, it is really just an accompaniment to my quilt.” I wasn’t really interested in doing anything with it.

But fast-forward to 2020; I said, “You know, I think I’m going to tweak this book and give it a main character – just kind of tweak it.” I am interested in doing more with it now, and that began the journey. I sent it out to a few publishing houses that accepted unsolicited manuscripts. I knew they probably wouldn’t respond because the response time is six months to a year. I was ok with waiting – and then I also sent it out to an agent because I had read that you’re more likely to be seen by a publisher if an agent sends it to them. So that was the journey.

Publishers didn’t write back, but the agency, the top Black literary agency in the country named “Serendipity,” wrote back the next day, and was like, “We are interested in talking to you about this. We think it’s great.” So, yea, it was serendipitous; that’s exactly it (Laughter). I think the timing was right.

Later, my agency told me that they had about a thousand books and manuscripts to read then, so they didn’t know how mine was suddenly there. But I’m so grateful. And they shopped around at different publishing houses, and now I’m with one of the top publishing houses in the country.

MH: Tell me how you taught yourself to quilt, specifically story quilt, because I’ve yet to hear that anywhere.

KT: I have always been a storyteller in some way. I started quilting to express emotion. My first quilt was about President Obama. When he was first elected, I was lost for words – you know – it was very difficult for me — someone who felt that verbal communication was easy. Still, it was hard to express what I was feeling. So, um, I know I wanted to create an art piece to show how I was feeling, but I’m not an artist. I wasn’t a trained artist; I didn’t go to art school. I love art, but I was afraid that I wouldn’t know how to express this artistically. I also wanted to make sure whatever type of art I used was somehow connected to my ancestry. So, I researched what kind of art women did in Africa and as enslaved people and came up with a story quilt, not just regular traditional quilting but more story quilting. We did do that in West Africa but some all over. Also, you know, enslaved women used quilts to keep their families warm but also to document their ancestry, family history, the bible stories they felt were important, so they created story quilts in that way, and I was thinking, this is how I want to express myself. So, I had to teach myself because no one was teaching that kind of quilting. I tried to go to a class teaching traditional quilting, and they said, “We’re going to make a table runner.” And I said, I wanted to make a quilt about Barack Obama, and they said this might not be the place for you – (laugh). So, I had to decide that I was going to teach myself. I was very committed. I read everything I could, and I also made a pact with myself that I would teach myself something new with every quilt.

I taught myself the technique of sewing and story quilting. I read everything I could about how to put the material together to create a picture. I call it fabric collage. But to tell a story, I had to decide what the story was first. You know, what I wanted to tell and how to do that visually. I’ll give you an example. My first story quilt about Juneteenth is four feet wide by six feet long. The picture is just like the book’s last picture: two people holding a baby up in the air in the sky at night. In that story quilt, I had to decide the message about Juneteenth. I wanted to talk about the ending of something and the beginning of something new. So, how could I depict that visually in just a small space because even if the quilt is six feet, it’s not enormous? I had to figure out what were the main aspects. It is probably what the process was in my head, but when I was in it, I was not thinking that. I often say that my quilts were created through me rather than by me. And I’ve said that through my whole journey. Sometimes I’ll finish a quilt and be surprised by what’s in front of me – like, wow, did I do that? I feel like I’m being guided by the ancestors. I’m being guided by creativity in space — which is sort of a space of being in the moment, not really thinking as you go, or at least I’m not. I feel like, at least for that big story quilt, what are the main aspects? How can I get that point across? One of the things I decided was I had to have two people symbolize the whole group that was enslaved. On one arm in the original story quilt, the arm that’s not holding the baby to the sky had broken chains. So, it’s like their wrists have the shackles, the chain is broken, and both have that —and the hand they are holding the baby up with is free of that chain. So that was the first symbol.

The baby means something else because this infant gets to live her life —I’m doing my fingers in quotation marks around freedom. Or at least without the burden of institutionalized enslavement. So that was trying to show, you know, that is our future. And there’s this full moon and something I hadn’t thought of, but one of the girls in the high school group that I was talking to asked me, “What does it mean? She is heading towards a full life?” And I said, I’m not sure that was my thought process, and I made it, but it does seem like a great symbol –and that’s what she saw. So, I feel like I have to be in tune with what I wanted the message to be in the small space.

MH: How many [Quilts] have you completed?

KT: Oh God, I mean about 15, if I don’t count the quilts for this book. This book has twenty-six original quilts. But they’re small, only 15 by 15. And I didn’t put them together in one big quilt, so they’re separated into small panels 15 by 15. So, if you consider that’s not much bigger than the pages of the book, then imagine all the little pieces of material that go into creating one picture. So, it took over a year to create those 26 quilts for the book.

MH: All those quilts are on these pages, right? There are 26 quilts, and you made them for the pages of the book?

KT: Yes. Originally, I did not want to do the illustrations; I felt like a painter should do the illustrations. But they [Holiday House Publishing} were determined I would do that. I handed the quilts along with my text, and they scanned each quilt on a rolling scanner, and that’s why you can see all the textures on each page. – I didn’t think I could do it, but I’m so glad I did.

Please visit materialgirlstoryquilts.com to continue journey. A Flag for Juneteenth by Kim Taylor is available through African American Literature Book Club