Shirley Sherrod: The “Martin Luther King Awards Dinner” Interview with Kam Williams

Shirley Sherrod is best known as the African-American government official fired in 2010 by the Obama administration for allegedly making racist remarks about a white farmer. However, a right-wing blogger had edited a video of her remarks to create that false impression.

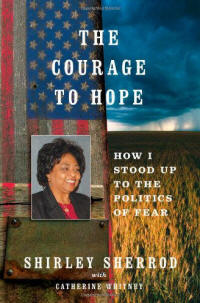

Shortly after being dismissed as the Georgia USDA State Director of Rural Development she was cleared by the administration, and President Obama apologized to her. Nevertheless, she decided to not return, opting instead to write a book her autobiography, The Courage to Hope: How I Stood Up to the Politics of Fear.

When

Shirley was 17, her father was killed by a white man in Georgia but no

charges were ever lodged. A cross was burned in their yard shortly

thereafter. The death of her father fostered her lifelong commitment to

fight for the civil rights of poor and minority farmers.

When

Shirley was 17, her father was killed by a white man in Georgia but no

charges were ever lodged. A cross was burned in their yard shortly

thereafter. The death of her father fostered her lifelong commitment to

fight for the civil rights of poor and minority farmers.

She is currently a leader of the Southwest Georgia Project, an organization she helped start years ago. The organization works primarily with female farmers, trying to get more women involved in agriculture, and also marketing vegetables to local school systems.

In 2011, under the leadership of Shirley and her husband, Charles, New Communities, an agricultural cooperative modeled after the Israeli Kibbutz concept, bought a large farm in Georgia. They are establishing an agricultural training center there, as well as a program bringing local blacks and whites together in partnership to promote racial healing.

In a famous quote from Shakespeare’s Othello, Iago notes that, "Who steals my purse, steals trash… But he that filches from me my good name… makes me poor indeed.” Here, Shirley talks about the tarnishing and restoration of her reputation, and also about delivering the keynote speech at the 26th Annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Awards Dinner in Glen Burnie, MD on Friday, January 17.

Shirley Sherrod — The “Martin Luther King Awards Dinner” Interview with Kam Williams

Kam Williams: Hi Ms. Sherrod. I’m honored to have this opportunity to speak with you.

Shirley Sherrod: Thank you, Kam.

KW: You’re delivering the keynote speech at the annual dinner in honor of

the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King. What did Dr. King mean to you?

SS: Well, Dr. King has long been my hero. I didn’t get to work with him

much, but my husband did in the early years. Dr. King gave his life, really,

to the struggle for everyone. And he believed in non-violence. That’s what

I’ve tried to do in terms of my life and my work, following the teachings of

God.

KW: In your biography, you talk about how your father was murdered by a

white man when you were 17. How did that tragedy shape you?

SS: I grew up on a farm and, prior to my father’s murder, I wanted to get

away from the farm, and away from South Georgia where the Jim Crow laws

absolutely controlled anything and everything we did. So, my goal was to

leave once I completed high school. But on the night of my father’s murder,

I made a commitment that I would not leave the South, that I would stay and

devote my life to working for change. So, my father’s murder has shaped the

course of my life even up to this very day.

KW: How did you avoid becoming embittered, especially after the grand jury

failed to indict the perpetrator who was never brought to justice?

SS: Given the way the system was, what could I do as I one person, other

than devote my life to fighting to make it different? If I had allowed

myself to be filled with hate, I probably wouldn’t even be alive, because

that hate could’ve killed me. That hate would’ve blinded me to my

contributions in terms of how I could make a difference. You can’t think

straight when you’re consumed by hate and focused on destroying someone

else. Instead, I was bent on trying to destroy a system that was not fair to

all of us, and I continue to do that.

SS: I can tell you that while I was in that situation, especially the first few days, you’re thinking that everyone in the country is believing something about you that is not true: that you’re a racist and that you refused to help a white farmer. It was a very bad place to be for someone like me who has devoted her life to working for change and for fairness for everyone. It was one thing for me to try to defend myself, and quite another to then have a white farmer step forward to say what I’d done for him. Oh my goodness! It makes you know that when you’ve done the right thing, you just don’t have to worry or even think about how you tell the story, because the truth will ultimately come out.

KW: Why do you think that that conservative blogger decided to edit your NAACP talk about tolerance to make you look like a racist?

SS: I kept wondering, “Who is this person and why did he choose me?” because I had never heard of him. I don’t have answer for that. He never apologized to me. I never had a conversation with him. I guess I was just a nobody to him, a nothing, somebody he thought he could literally destroy while trying to get at the NAACP.

KW: Reverend Florine Thompson asks: How did your personal theology inform

your response to being fired from your position?

SS: You have to approach people with the truth and with love, and with

what’s right. I was determined to get the truth out because I knew that the

truth would set me free.

KW: Reverend Thompson also asks: Where do you find fulfillment and purpose

in your life?

SS: I love helping other people. When I made that commitment to stay in the

South, to work for change, it meant devoting my life to working for and

helping others. I feel good when I know that I’ve saved someone’s farm, or

helped a family to get a home or access to credit. Or when I can get young

people to see that there’s more to life than just trying to make the biggest

dollar for yourself.

KW: Leon Marquis asks: Why didn't you sue President Obama for firing you?

SS: That’s a good question that I really don’t have an answer for.

KW: Attorney Bernadette Beekman says: What happened to you was so awful, I

don't know how you stood up to it, but I like the fact that you filed a

lawsuit. She says: Aside from telling your personal story as well as how the

right-wing media had a frenzy taking your remarks out of context, what did

you hope to accomplish by writing your autobiography?

SS: I had been telling that story about my transformation and the white

farmer for 24 years. And people often suggested that I write a book about

it. But I never had the time to until all of this happened to me. Suddenly I

was out of a job and being encouraged to write my story by so many people

that I just went ahead and did it.

KW: Bernadette also asks: Would you encourage young people to go into

farming today if they do not have enough independent financial resources?

SS: The traditional farm, the peanuts, the cotton, the corn, is probably not

the thing to do, because you’re up against big farmers who can afford all

the equipment to grow those kinds of crops. But we need healthy food. We’re

being encouraged to eat more vegetables. Our school systems are being

encouraged to buy locally. So, we need farmers who can produce that food. We

were recently helping a school plant broccoli and cabbage in a garden, and

this 8 year-old boy said, “I don’t eat food from the Earth, because it has

nature on it.” When we asked him where he got his food, he said, “From the

grocery store.” When we tried to explain where that food came from, he put

his hands over his ears, shouting “Stop! Stop! That’s gross.” Our children

need to learn how to produce food. That’s where we came from.

KW: Bernadette asks: What do you think of the locavore movement where

eco-conscious people concerned about sustainability only eat locally-grown

food?

SS: We have landowners, small growers. We have people who are holding onto

land that was acquired by their families after slavery. They need to produce

some of the food we eat, so they can pay the taxes and hold onto the

property. Taxes keep going up. We, and by we I mean black people, are

rapidly becoming a landless people. Our ancestors, coming out of slavery,

acquired more than 15 million acres of land. Today, we’re probably down to

less than 2 million acres.

KW: Did you know J.L. Chestnut, the late civil rights attorney? I know that

he sued the government on behalf of black farmers in the South?

SS: Yes I did. He was such a great person. There was never a dull moment

around him. And when you got Chestnut and Dr. Lowery [former SCLC President

Joseph Lowery] together, oh my goodness! [Chuckles]

KW: How do you feel about GMOs being shipped to Africa and elsewhere in the

Third World?

SS: I have a problem with that. I don’t think we yet know the full brunt of

genetically-modified seeds.

KW: Children’s book author Irene Smalls asks: How do you feel about the

Obama administration today?

SS: I’ve remained a supporter of the Obama administration, even at the

height of my ordeal. There’s a lot that he could do differently, but so much

of what he’s tried to do has been blocked by the Republican officeholders. I

think that he could have been a much better president with more support. So,

I’m still supportive of him.

KW: Irene is also wondering whether you have any advice for individuals in

government service?

SS: If you’re in it for the money, then you’ll do what you have to do to

survive. But if you’re in it to do the right thing, then it might mean that

you won’t get to stay there, but at least you can say, “I did what was right

while I was there.”

KW: Irene then asks: What do you want the world to know about Shirley

Sherrod?

SS: That Shirley Sherrod is someone who is committed to helping others. I

love people, and I love doing things that make a difference.

KW: Editor/Legist Patricia Turnier asks: Was it a cathartic experience for

you to write your autobiography?

SS: Yes, it’s just amazing to look back over your life and the work that

you’ve done. It’s really something!

KW: Patricia also asks: What was the most important lesson you learned from

the experience related to the doctored videotape?

SS: The support that I received from people all over the country was really

heartwarming.

KW: Patricia says: Many women in powerful positions all over the world still

face employment discrimination. What advice do you have for them and how can

they continue to break the glass ceilings?

SS: That’s a difficult one. [Chuckles] You can’t give up. Sometimes you get

knocked down, but you have to get back up, fighting. You have to think about

the others who come behind you as well. And you have to think of the example

that you set for others.

KW: Larry Greenberg asks: How do you feel about the cultivation of hemp, as

a former official with the Department of Agriculture?

SS: Well, where it’s legal, I guess it’s a great crop to grow.

KW: Irene’s asks: What’s up next for you?

SS: I talk about it in the last chapter of my

book which deals with hope and a piece of property that’s been acquired

which was a former plantation. We have a racial healing project to teach

young people farming and our history so we don’t end up reliving it.

KW: The bookworm

Troy

Johnson question: What was the last book you read?

SS: I have to think… I read quite a few…My

Black Family, My White Privilege is the most recent one I read.

And before that, Michelle Alexander’s book,

The New Jim Crow.

KW: What is your favorite dish to cook?

SS: Gosh! Let’s see. I have two. Sweet potato soufflé and macaroni and

cheese.

KW: The Ling-Ju Yen question: What is your earliest childhood memory?

SS: Learning to drive a tractor on the farm. I was probably five years-old.

My parents kept having children, trying to have a son. They had five

daughters in a row. We were his girls, but we each had a boy’s nickname.

Mine was Bill. My mother was finally pregnant with my brother when my father

was murdered.

KW: When you look in the mirror, what do you see?

SS: Well, I see someone who’s aging now, and someone who kept a commitment

made many, many years ago, and who today is trying to be an example for

young women.

KW: If you could have one wish instantly granted, what would that be for?

SS: One wish? I wish that somehow, some way we could learn to live together

in this country.

KW: The Tavis Smiley question: How do you want to be remembered?

SS: As someone who was dedicated to others and to making a difference.

KW: Thanks again for the time, Shirley, and I wish I could be there for your

keynote speech at the Martin Luther King dinner.

SS: Thanks, Kam.

The 26th Annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Awards Dinner will be held at

La Fountaine Bleue in Glen Burnie, MD. Those to be honored for their actions

that help keep the legacy of Dr. King alive include: U.S. Senator Barbara

Mikulski, Gerald Stansbury of the Maryland NAACP, Larry White Sr., Marc L.

Apter, Dr. Oscar Barton Jr., Antonio Downing, Sylvia Rogers Greene, Kathy

Koch, Julie C. Snyder and the Community Foundation of Anne Arundel County.

The 26th Annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Awards Dinner will be held at

La Fountaine Bleue in Glen Burnie, MD. Those to be honored for their actions

that help keep the legacy of Dr. King alive include: U.S. Senator Barbara

Mikulski, Gerald Stansbury of the Maryland NAACP, Larry White Sr., Marc L.

Apter, Dr. Oscar Barton Jr., Antonio Downing, Sylvia Rogers Greene, Kathy

Koch, Julie C. Snyder and the Community Foundation of Anne Arundel County.

The MLK Jr. Awards Dinner is presented by the Annapolis based Martin Luther

King Jr. Committee, Inc. at La Fontaine Bleue, 7514 Richie Highway, Glen

Burnie. This year’s dinner tickets are $60 ($65 after January 14th). VIP

tickets are $100 including premium seating and a private reception before

the dinner with hors des oeuvres and an open bar.

Tickets may be purchased by phone at 410-760-4115 or on-line at

www.mlkmd.org.

Related Links