-

Posts

2,402 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

91

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Events

Status Updates posted by richardmurray

-

The truth of law enforcement groups in the usa, is all have a history of severe abuses which when you parallel them to the crimes they prevent, i argue far outweighs what they prevent, sequentially making them dysfunctional. The tragedy is the populace in the usa who actually need aid by law enforcement is a fraction of a percentage of the whole but their mouthpiece is amplified by the communication channels of the wealthy in the usa who know false problems make great news.

A police officer took a teen for a rape kit.

Then he assaulted her, too.

Hundreds of law enforcement officers have been accused of sexually abusing children over the past two decades, a Post investigation found

A teen who was sexually abused by a New Orleans police officer.

Story by Jessica Contrera,

Jenn Abelson and

John D. Harden

Updated March 14, 2024 at 5:54 p.m.Originally published March 14, 2024

The 14-year-old did not want to go to the emergency room. Her mother had begged her. Her therapist had gently prodded. And now there was a police officer in her living room.

“You really should think about it,” he said.

He introduced himself as Officer Rodney Vicknair. His New Orleans Police Department cruiser was waiting outside, ready to take her to the hospital for a rape kit. Early that morning, the girl said, a 17-year-old friend had forced himself on her.

Under the police department’s rules, a case like this was supposed to be handled from the start by a detective trained in sex crimes or child abuse. But on this afternoon in May of 2020, it was Vicknair, a patrol officer with a troubled past, who knocked on the girl’s door.

He tried to coax her into changing her mind. “If I’m a young man that has done something wrong to a young lady and she doesn’t follow up and press the issue,” Vicknair said as his body camera recorded the conversation, “then I’m gonna go out and do it to another young lady.”

“And it’s gonna be worse, maybe, the next time,” Vicknair said, “because I’m gonna think in my head, ‘Oh, I got the power. I can go further this time.’ ”

The girl didn’t want that. She just wanted this to be over.

She didn’t know it was only the beginning. Four months later, police would arrest a man for sexually assaulting the girl. But it wouldn’t be her teenage friend. It would be Officer Rodney Vicknair.

The day the 14-year-old met 53-year-old Vicknair was the day the officer began a months-long grooming process, prosecutors would allege. Within hours of meeting the girl, Vicknair wrapped his arm around her while they took a selfie. He let her play with his police baton. He joked with her about “whipping your behind.” He showed her multiple photos of a young woman dressed only in lingerie.

Officer Vicknair talks to teen at the hospital

0:23

The Washington Post blurred the teen’s face to protect her identity. (Obtained by The Washington Post)

Americans have been forced to reckon with sexual misconduct committed by teachers, clergy, coaches and others with access to and authority over children. But there is little awareness of child sex crimes perpetrated by members of another profession that many children are taught to revere and obey: law enforcement.

A Washington Post investigation has found that over the past two decades, hundreds of police officers have preyed on children, while agencies across the country have failed to take steps to prevent these crimes.

At least 1,800 state and local police officers were charged with crimes involving child sexual abuse from 2005 through 2022, The Post found.

Abusive officers were rarely related to the children they were accused of raping, fondling and exploiting. They most frequently targeted girls who were 13 to 15 years old — and regularly met their victims through their jobs.

The Post identified these officers through an exclusive analysis of the nation’s most comprehensive database of police arrests at Bowling Green State University, as well as a review of thousands of court documents, police decertification records and news reports.

In case after case, officers intentionally earned the trust of parents and guardians, created opportunities to get kids alone and threatened repercussions for broken silence. Unlike teachers and priests, they did it all while wielding the power of their badges and guns.

Chuck Wexler, who leads the Police Executive Research Forum, a law enforcement policy and training organization, said the number of officers charged with these crimes is “very troubling.”

“Whatever we can do to prevent this and hold those accountable will help restore the trust in the police,” Wexler said.

But while many school systems and churches have created practices and policies to root out predators, law enforcement agencies have largely treated child sexual abuse as an isolated problem that goes away when an officer is fired or prosecuted — rather than an always-present risk that requires systemic change.

There is no national tracking system for officers accused of child sexual abuse. At a time when police departments across the country face staffing shortages and are desperate to hire, there are no universal requirements to screen for potential perpetrators. When abuse is suspected, officers are sometimes allowed to remain on the job while investigations of their behavior are left in the hands of their colleagues.

In the New Orleans Police Department, child sexual abuse has been a problem before. The city recently paid $300,000 to settle a lawsuit over its 1980s Police Explorers program led by a lieutenant who was accused of sexually exploiting 10 boys. The case was investigated by the head of NOPD’s juvenile sex crimes unit — who in 1987 was convicted of child sex crimes, too.

In more recent years, two officers remained on the force after they were accused of abusing young girls. Then they sexually assaulted other children. They are among six NOPD officers who have been convicted of crimes involving child sexual abuse since 2011.

Vicknair is the latest. His case reflects larger problems that police departments confront in conducting background checks, identifying red flags and responding to complaints of inappropriate behavior. To reconstruct what happened in New Orleans, The Post obtained hundreds of internal law enforcement records, hours of video footage and dozens of text messages.

Vicknair was hired in 2007 despite a record that included multiple arrests and a conviction for battery on a juvenile. His sexually charged interactions with the girl he drove to the hospital, though witnessed by another officer, went unreported to superiors. He frequently visited the girl’s home in the summer of 2020, telling new cops he was training that they should stay in the car while he went inside alone. And when concerns about Vicknair’s behavior were reported to the department, police officials allowed him to remain on duty for a week. During that week, the girl said, Vicknair sexually assaulted her.

Reached by phone last year, Vicknair declined to comment for this story. In November of 2022, he pleaded guilty to violating the girl’s civil rights, admitting that he locked her in his truck and touched her under her clothing.

The city of New Orleans and its police department also declined to discuss the case with The Post, citing pending litigation. The victim and her mother filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the city and its superintendent of police in 2021.

In court filings, the city has repeatedly denied that the police department is responsible for the girl’s abuse, arguing that Vicknair was not on duty at the time of the assault he pleaded guilty to and was not acting on behalf of NOPD “while performing any of the inappropriate actions alleged against him.”

Soon, the case will go before a jury. A trial over what, if anything, the girl is owed by NOPD was scheduled to begin March 18. But hours after The Post published this story online, a judge ordered that the trial be delayed.

With the permission of the victim and her mother, The Post is identifying the girl only by her middle name, Nicole.

At 14, Nicole was barely 100 pounds. She hadn’t yet gotten braces. A large stuffed giraffe still watched over her bedroom.

She’d spent her preteen years in custody battles between divorced parents, in a domestic violence shelter with her mom and in a hospital for self-harm. She believed all adults just wanted to tell her what to do. But on the day Vicknair persuaded her to go to the emergency room and then sat with her and her mother for hours, Nicole felt like he actually wanted to listen.

“If you ever just want to shoot, talk, text me,” he told her as his body camera continued recording. “You having problems, just need somebody to talk to, if I’m working I’ll come swing by and talk to ya, okay? ... We’ll go get some ice cream in McDonald’s or something.”

Nicole saved Vicknair’s number in her phone as “Officer Rodney.”

“Now hit call so I know it’s you and I can save you as a contact,” Vicknair said before leaving. He lifted his phone and aimed his camera down at her. Her bare legs were dangling off the hospital bed.

“No,” Nicole objected, raising her hand to block his view.

Vicknair took the picture anyway. “There we go,” he said. “Perfect.”

icole was just a year old when Vicknair applied for the job that would make it possible for him to meet her and other children.

“I always wanted to be a police officer in New Orleans,” Vicknair wrote on his NOPD application in 2006. “I truly love helping + serving my community.”

He was far from the typical police recruit. He’d worked as an EMT and a hospital security guard, but he was about to turn 40 — an age that would have disqualified him from joining some departments at the time. At 5-foot-11, he weighed 237 pounds. He had lifelong tremors that regularly made his hands shake.

A department spokesperson told The Post that, today, NOPD has some of the most stringent hiring requirements in the state of Louisiana. Since entering into a consent decree with the Justice Department in 2012, NOPD has been working to reform its policies and practices.

But at the time Vicknair applied, NOPD was in disarray following Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Public outcry over officers’ actions had resulted in intense scrutiny from the outside and low morale on the inside. Recruiters needed to find people willing to wear the badge. According to the Justice Department, NOPD began lowering hiring standards and performing less rigorous background checks.

In his application, Vicknair disclosed to the department that he’d previously been charged with disturbing the peace and aggravated assault. Just the year before he applied, deputies from the St. Tammany Parish Sheriff’s Office were called when Vicknair reportedly brandished a knife at his ex-girlfriend and beat a man she was dating.

Citing the “potential for future violence, as well as threats made by Mr. Vicknair in the presence of deputies,” law enforcement seized Vicknair’s knife and his gun before taking him to jail, according to a police report included in his background check.

The charges were eventually dropped. Vicknair’s ex-girlfriend, Denise Trower, told The

that she asked authorities to stop pursuing the case because she was afraid of what Vicknair might do if she didn’t. During their relationship, she said, Vicknair choked her and held a loaded gun to her head.

“He had threatened that he would make sure somebody did something to my son,” Trower said.

Without calling Trower to learn more about what happened, the NOPD background investigator wrote that the arrest “should not reflect poorly” on Vicknair’s application.

The incident was not the only time Vicknair had been charged with a serious crime. In 1987, he was convicted in Ascension Parish of simple battery on a juvenile — a part of his past he did not disclose to NOPD. He was sentenced to $50 in fines or 10 days in jail.

Three of Vicknair’s family members told The Post that he was charged after he had what they described as a sexual relationship with a minor. Vicknair was 20 years old. The girl, whom The Post is not identifying, was a preteen at the time. She did not respond to interview requests.

There is no indication that the background investigator looked into the simple battery conviction; he didn’t appear to know it existed. Though The Post obtained a record of Vicknair’s conviction from the court, the background investigator reported in his notes that Vicknair had no criminal record in Ascension Parish.

Records show the NOPD background investigator also did not contact anyone in Vicknair’s family.

Vicknair’s sister, Kim Vogel, said that if she had been contacted, she would have told the department not to hire her brother. She described him as loyal, generous and eager to help other people. But she also said his history of anger and violence still gives her nightmares.

“I don’t think he should have been a police officer, and I hate even bringing that out there,” Vicknair’s sister said. “But I also blame that on the police department, because I know they do background checks, they do psychological tests and all that. And they missed all of it.”

Vicknair did undergo a computerized voice-stress analysis, a type of lie detector test.

“Did you intentionally withhold any information from your employment application?” the examiner asked.

Vicknair answered no. The NOPD investigator rated his application as “acceptable.” He was hired onto the force in March 2007.

During the next 12 years, he was internally investigated for allegations of misconduct a dozen times, according to NOPD records.

In eight of the cases, which included accusations of unauthorized force, theft of $1,000 and drug possession, the department found no evidence of misconduct, could not determine whether the wrongdoing occurred or deemed his actions justified. Vicknair was not disciplined.

Records show he was formally punished twice for reckless driving and twice for acting inappropriately toward women who claimed he had mocked or harassed them while on duty. The most severe consequence he received was a five-day suspension.

In 2016, he was promoted to become a mentor to new officers while he patrolled the neighborhood where he would meet Nicole.

After the swabbing was over, after she stopped hyperventilating, after she stayed at the hospital to ensure she didn’t hurt herself, Nicole was discharged. Then she called Officer Vicknair.

“Let me know when back home and I’ll come check on you,” Vicknair texted the 14-year-old on May 26, 2020. He’d started messaging her the night he met her, by sending a GIF of a waving puppy.

In the weeks that followed, he began showing up at her house in uniform. He’d sip a Dr Pepper while talking about the headlines on Fox News. He’d lecture Nicole about staying out of trouble.

Nicole’s mother, Rayne, witnessed it all. Rayne — The Post is identifying her by her first name to protect Nicole’s privacy — had grown up with a sheriff’s deputy for a grandfather. She trusted law enforcement and raised her daughter to feel the same way.

So Rayne encouraged Vicknair to follow up on his idea to take Nicole out for ice cream. She called him when Nicole was having a breakdown. She invited him to visit Nicole on her 15th birthday.

Rayne didn’t worry when she discovered that the 53-year-old officer was talking to her daughter on the phone late at night that summer. She was grateful that Nicole, who had become silent and surly in the weeks following her sexual assault report, was finally opening up to someone. Someone who could be a role model.

“She would be like, ‘Oh, I had the best talk with Rodney last night, Mom. He’s so nice,’” Rayne remembered.

The interest Vicknair was taking in her daughter was so different from how NOPD first responded. On the morning in May when Rayne discovered her daughter on the couch with her 17-year-old friend, two other patrol officers were the first to be dispatched to a report of attempted rape at her house.

It was 5:21 a.m. The teenage boy had already fled. Records show the officers spent 11 minutes at the house before leaving. They appeared to take no further action.

Their response was exactly what the federal government had spent years trying to fix at NOPD. As a part of the 2012 consent decree, the Justice Department’s investigators found that officers were repeatedly mishandling reports of sexual assault. NOPD’s investigations were “seriously deficient, marked by poor victim interviewing skills, missing or inadequate documentation, and minimal efforts to contact witnesses or interrogate suspects.”

Years later, NOPD’s special victims unit continued to be understaffed and overwhelmed. According to a recent Justice Department report, the unit closed out 3 percent of cases in 2022.

Several hours after the first officers left Nicole’s house, her therapist called to report the assault a second time. NOPD sent Vicknair and two other patrol officers to her house. Then a special victims detective, Kimberly Wilson, arrived. Body-camera footage shows she spent a total of four minutes with Nicole before saying she had somewhere else to be.

She left Vicknair and another officer to drive and sit with the teen at the hospital. Wilson stopped by later that afternoon, but didn’t interview Nicole until two days later.

“I told him to stop,” Nicole said about the 17-year-old. “He said ... ‘No, let me get it over with.’ ”

Wilson declined to comment on her investigation. There is no record that Wilson ever interviewed the 17-year-old, and it is unclear from the case file whether Nicole’s rape kit DNA was tested by the crime lab.

Instead of progress in her case, Nicole got visits from Vicknair.

The first time Vicknair came over when her mother wasn’t home, Nicole remembered, he asked if she owned any booty shorts.

“What was running through my mind at that time was ‘Oh, he’s just a guy,’ ” Nicole said. “You know, that’s how guys think.”

The more he came over and called, the more he learned about what Nicole had been through in her life. Rayne told the officer that her daughter was the “textbook poster child for daddy issues.” Nicole told him about sneaking into bars on Bourbon Street while her mom worked nights — and about the older men who bought her drinks there.

Vicknair began warning her, Nicole said later, that he could report her mom for child endangerment and get her thrown in jail. He told Nicole he could arrest anyone. He whacked her with his baton.

She’d been taught to be afraid of strangers who might want to kidnap her, not adults in positions of authority who increasingly tested her boundaries.

So she told no one when Vicknair’s texts shifted from “Lion King” GIFs to tongue emojis. Or when he confided in her about his own childhood trauma, then asked her to send nudes. Or when he went from telling her he wanted to touch her to actually doing it.

“I passed your house earlier,” Vicknair texted Nicole on Sept. 7, three and a half months after he met her.

“Stalker,” she replied.

“You like it,” he texted back.

Later, she would wish she had told him to leave her alone. “I just kept going along with shit,” Nicole remembered. “He knew where we lived, you know?”

Vicknair would admit to investigators after he was arrested that he visited Nicole at her house at least a dozen times.

But it wasn’t anyone within NOPD who raised concerns about Vicknair’s behavior. It was Nicole’s mother, who in September found a photo on her daughter’s phone. In it, Vicknair’s tattooed arms were wrapped around Nicole, pressing the back of her body into the front of his.

Nicole told her mom only that Vicknair once followed her in his police cruiser while she was on a run, yelling “Nice ass!” out the window. Rayne consulted with Nicole’s therapist. They both worried there was more going on.

How, Nicole’s mother began to wonder, do you report the police to the police?

On Friday, Sept. 18, 2020, nearly four months after Vicknair met Nicole, the head of the New Orleans Police Department received a text.

“It’s about potential sexual abuse of a minor by an officer,” read the message to then-Superintendent Shaun Ferguson.

The text was sent by Susan Hutson, then the city’s independent police monitor, a civilian oversight agency created after Hurricane Katrina. Hutson’s job included listening to citizens’ complaints about police and trying

When the interview was over, investigators did not immediately seek a warrant for Vicknair’s arrest. Instead, they asked Nicole to call the officer who she had just said assaulted her — and ask him if he would do it again.

She was deeply uncomfortable. But she did as she was told. She pulled up “Officer Rodney” on her phone.

[Excerpt from call]

Nicole:

Can we do what we did in your truck again?

Vicknair:

Um.

In the background, a girl’s voice can be heard saying, ‘Love you, Dad!’

Nicole:

Can we?

Vicknair:

I don’t know if it’s your phone or my phone, it’s breaking up.

[Vicknair ended the call.]

Vicknair already knew that Nicole was going to the child advocacy center for a forensic interview that day. Nicole told him the interview was about another man, one she’d met on Bourbon Street.

Now, Nicole feared, Vicknair knew what was going on.

Less than an hour after Vicknair hung up on Nicole, he got into his Toyota Tundra, the same vehicle Nicole said she’d been assaulted in two nights earlier. He was followed by an officer who’d been sitting outside his house, conducting surveillance.

The officer quickly lost sight of Vicknair’s truck.

When the truck returned, it was gleaming, with fresh gloss on the tires and exterior. The officer wrote in his surveillance report that it appeared Vicknair had gone to get his vehicle detailed.

If there was any evidence — or underwear — remaining in the truck, it had just been washed away.

to get something done about them.

Often, that meant contacting NOPD’s version of internal affairs, known as the Public Integrity Bureau. While some police departments turn to outside agencies to conduct investigations when one of their officers is suspected of committing a serious crime, NOPD investigates its own.

Hutson notified Ferguson and then-integrity bureau leader Arlinda Westbrook that same Friday evening. Sgt. Lawrence Jones, a criminal investigator with the public integrity bureau, did not begin looking into Vicknair until the following Monday, Sept. 21. (Jones and Westbrook did not respond to interview requests from The Post. Ferguson, who retired in 2022, declined to comment.)

Jones first spoke with Nicole and her mother that Monday. Sitting in on the call was Stella Cziment, the deputy police monitor at the time.

Listening to Nicole talk, Cziment later told The Post, she could tell the girl was afraid to speak honestly about Vicknair. She called him her friend, and was clearly trying to protect him. They weren’t certain that sexual abuse had already occurred. But the red flags about the officer’s behavior were obvious, Cziment said. She assumed that NOPD would act to remove Vicknair from duty as quickly as possible.

“What we were scared of was the amount of access he had to the child,” Cziment said.

But Vicknair was not removed from active duty that day, even after Jones, the investigator, visited Nicole’s house and saw the photo of Vicknair, in uniform, pressing Nicole into his body and texts in which the officer called her sweetie, honey, buttercup, baby girl and boo.

Vicknair remained on patrol the next day, even after Jones reviewed the body-camera footage from when Vicknair took Nicole to the hospital and showed her photos of a nearly naked woman.

The entire week, Vicknair kept his job, his badge, his gun. Not until Friday, Sept. 25, seven days after the text to the head of police, was Nicole interviewed by someone specially trained in child abuse at the New Orleans Child Advocacy Center.

“I try to keep him happy,” Nicole told the forensic interviewer, according to a videotaped recording obtained by The Post. “He’s a cop, so it’s not like he’s going to get in trouble for any of this.”

The last time she’d seen Vicknair, she said, was just two days earlier. He’d come to her house while on duty, then returned after his shift. She went out to his truck and got inside.

“Did something happen?” the interviewer asked.

Nicole squirmed in her chair, her Converse high-tops shaking.

“I just can’t say it,” she said.

“I’m not gonna put words in your mouth,” the interviewer said.

“Fine,” Nicole said. “He stuck his finger in my, in my — ”

She pointed downward. At 15, she was too embarrassed to name her own body parts. The interviewer asked her one more time, and then her story came rushing out. How weird it felt. How scared she was.

She tried to hug him goodbye, she said, but then, “He stuck his finger in one more time and was like, ‘Just one more taste.’ ”

That night in Vicknair’s truck, Nicole said, he asked her for a favor. He wanted to keep her underwear.

He still had them, she said.

By 2 a.m. the next day, Vicknair was inside an interview room, handcuffed to a table.

“Rodney, first of all, I want to thank you for sitting down and talking with us,” said Jones, seated across from his colleague.

“I didn’t have much choice,” Vicknair balked.

Sheriff’s deputies had knocked on the door of Vicknair’s home just before 1:30 a.m. on Sept. 26.

Vicknair came out in only his boxer briefs and lit a cigarette. He kept smoking as they cinched cuffs behind his back.

When he learned during his recorded interview that his arrest was related to Nicole, he laughed.

“On her?” he said. “Okay.”

Over the next hour and a half, Vicknair switched between denials and explanations for what he couldn’t deny. Yes, he’d gone to Nicole’s house just before midnight two nights earlier — but only because she’d asked him to sniff her to see if she smelled like weed, he said. Yes, he had sexual photos of her on his phone — but he’d only taken screenshots of her Snapchats “in case something ever did happen,” he said. Yes, he told her which of her thongs were his favorite and that she had “a nice ass for your age.”

“If that was inappropriate, then so be it. It was inappropriate,” he said. “But there was never nothing sexual.”

Vicknair was adamant that he did not penetrate her or take her underwear.

“I care about her the same way I cared about several other girls and boys that I’ve given my business cards to and talked to them,” Vicknair said.

He accused Jones of trying to “make a case or something of a disturbed child.”

“The issue is that we have a 52-year-old, 15-year, veteran police officer who’s seeing … this 15-year-old girl regularly,” Jones said.

“That ain’t nothing,” Vicknair said. “I talk to a lot of younger people four or five times a week.”

At no point during the interview did Jones ask for the names of the other young people Vicknair claimed to be talking to, including a runaway girl he mentioned specifically. There is no indication in the internal case records that NOPD ever conducted a review of other children Vicknair had interacted with.

“We just hope,” Jones told Vicknair, “none of them come calling here.”

Charged with sexual battery, indecent behavior with a juvenile and malfeasance in office, Vicknair spent a week in jail before posting a $55,000 bond.

He submitted a letter of resignation to the police department in January 2021.

His wife of five years filed for divorce. He suffered three heart attacks and a stroke.

The Justice Department, which took over his prosecution from Orleans Parish, charged him with deprivation of rights under the color of law, the same federal charge often filed against officers who use excessive force. In November 2022, Vicknair agreed to plead guilty.

In his plea, he signed a statement admitting that he made sexual comments, requested and received sexually explicit photos and touched Nicole’s genitals under her clothing without her consent inside his locked vehicle.

In exchange, prosecutors asked the judge to send him to prison for seven years.

On March 8, 2023, Vicknair shuffled into a federal courthouse for his sentencing hearing using a cane. For the first time since the night in his truck, he was in the same room as Nicole.

She was 17 years old. She wouldn’t stick with therapy. She and her mother fought so often that she’d moved with a boyfriend to California. There, she reasoned, she would never have to see an NOPD cruiser again.

She spent her days sleeping and watching documentaries about sex crimes and murders, telling herself that what happened to her wasn’t as bad as what happens to other girls. She spent her nights playing “Call of Duty” online with strangers, nearly all of them boys and men. She shot and swore and screamed at them, and reminded herself that none of them knew where she lived.

“Is there something you would like to say to the court?” the judge, Lance Africk, asked her.

She stood at a microphone in a stiff white button-down shirt she’d purchased just hours before. She hoped it would make the judge take her seriously.

All day, people had been telling her how “strong” she was. She thanked them, saying nothing about her recurring nightmare in which uniformed, tattooed arms were wrapping around her again. Or the knife she kept in her closet in case they ever did.

“To her, he appears as a helping hand, but little does she know he had other plans,” Nicole said, reading a poem she’d written as her victim impact statement.

Vicknair, coughing behind a mask, was watching her.

“He tears her down and makes her suffer, yet she comes out 10 times tougher. Now every night the light stays on, scared he will return. She hopes he has had a change in heart and that he has learned.”

The judge told her she was strong. He told her mother not to feel guilty. Then he began to narrate, in graphic detail, everything Vicknair had done to Nicole.

“I guess he was thinking: Who is going to believe a 14- or 15-year-old over me, a New Orleans police officer?” the judge said. “He served himself, not this young, trusting child.”

But the child he was talking about was no longer there. The moment the judge began describing it all again, Nicole ran out of the courtroom in tears.

While she hovered over a bathroom sink, trying not to vomit, the judge announced that he was refusing to accept the plea. He believed seven years was not enough time. He told both sides to come back the next week.

When they did, Africk agreed to a new deal. He sentenced Vicknair to prison for 14 years, Nicole’s age when he met her.

Two months later, Nicole was scrolling on her phone when she started to shake. She rubbed her eyes, thinking she must be imagining the notification that had just appeared on her screen.

A Snapchat account with a familiar name was trying to contact her.

A bitmoji of a dark-haired man was waving at her, surrounded in confetti.

“Officer Rodney,” the notification said, “added you as a friend.”

Vicknair was not yet in prison. The judge had granted him time to seek medical care before he turned himself in.

Vicknair’s heart problems had become something more. After he was sentenced, doctors had discovered a fast-growing tumor in his brain. It appeared that Vicknair was trying to contact Nicole from his hospital bed. She did not reply.

Vicknair had two brain surgeries before his brother and ex-wife drove him to Massachusetts to report to federal prison. He continued to deny to his family members that he had sexually abused Nicole. He continued to be paid police retirement benefits of more than $2,700 per month, records show. Louisiana has no law that automatically disqualifies police officers convicted of serious crimes from receiving their pensions.

Days after Nicole’s 18th birthday, Vicknair was rolled into prison in a wheelchair.

Most of his sentence was spent at a federal prison medical facility in North Carolina, where he received chemotherapy and radiation.

He served less than six months. Vicknair died on Jan. 1, 2024.

Nicole was at a restaurant in California when she heard the news from an attorney in her civil rights lawsuit. She wanted to feel relieved. Instead, she kept thinking about how little time Vicknair served. And how, before he died, he’d given a deposition in her civil case. Under oath, he returned to denying that he’d ever assaulted her.

Now, it felt like not a single adult was taking responsibility for what happened to her. If she gave up her lawsuit against the city, no one ever would.

She’d already endured a day-long deposition in December, when an attorney representing New Orleans asked her questions such as, “Was there any sexual meaning to him hitting you with the baton?” In January at a settlement conference, she listened to the lawyers debate just how much her trauma was worth.

The same city that had once charged Vicknair with sexual battery and malfeasance in office was now claiming his assault was “wholly unrelated” to his job.

But a judge disagreed, ruling in February that the city was, in fact, liable for Vicknair’s actions. It would still be up to a jury to decide how much New Orleans owed Nicole — and whether NOPD was at fault for hiring Vicknair in the first place.

As the March trial date crept closer, Nicole’s stomach started to ache. The pain kept getting worse, until it was so agonizing that she couldn’t sleep. But for days, she refused to go to the emergency room.

When she finally gave in, she reminded herself that this ER was different. That she was no longer 14. That Vicknair was not beside her. She still hyperventilated through every exam.

She learned that what could have been a relatively minor issue had become a serious kidney infection. It would take weeks for her to recover.

While she waited for the pain to ebb, her attorneys in New Orleans prepared for her trial by deposing the city’s police officials. Why, they asked, had the city hired someone with a history of arrests? Why had no one flagged an officer repeatedly returning to the home of a child who had reported a sexual assault? Why hadn’t Vicknair been pulled from active duty as soon as the photo surfaced of his body pressed against Nicole’s?

They wanted to understand what NOPD was doing to ensure that what happened to Nicole didn’t happen to another child. But when the sergeant in charge of all department policies was asked that question, he could not cite a specific policy or training method that had changed because of the case.

“You don’t know of anything NOPD has done differently,” the attorney confirmed, “to prevent another Officer Vicknair?”

The sergeant’s answer was one word:

“Correct.”

URL

-

Title: No pics

Artist: Lisa Tillman Pritchard < https://www.etsy.com/shop/ltpartllc1/ , https://www.tiktok.com/@ltpartllc>Prior post

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2613&type=status

Lisa Tillman Pritchard post

https://aalbc.com/tc/search/?&q=lisa%20tillman%20pritchard&type=core_statuses_status&quick=1&author=richardmurray&search_and_or=and&sortby=newest -

Title: Neo Soul

Artist: Lisa Tillman Pritchard < https://www.etsy.com/shop/ltpartllc1/ , https://www.tiktok.com/@ltpartllc>Prior post

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2612&type=status

Lisa Tillman Pritchard post

https://aalbc.com/tc/search/?&q=lisa%20tillman%20pritchard&type=core_statuses_status&quick=1&author=richardmurray&search_and_or=and&sortby=newest -

Title: Natural Order of Haircare Series

Artist: Lisa Tillman Pritchard < https://www.etsy.com/shop/ltpartllc1/ , https://www.tiktok.com/@ltpartllc>Prior post

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2611&type=status

Lisa Tillman Pritchard post

https://aalbc.com/tc/search/?&q=lisa%20tillman%20pritchard&type=core_statuses_status&quick=1&author=richardmurray&search_and_or=and&sortby=newest -

Title: morning glory

Artist: Lisa Tillman Pritchard < https://www.etsy.com/shop/ltpartllc1/ , https://www.tiktok.com/@ltpartllc>Prior post

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2610&type=status

Lisa Tillman Pritchard post

https://aalbc.com/tc/search/?&q=lisa%20tillman%20pritchard&type=core_statuses_status&quick=1&author=richardmurray&search_and_or=and&sortby=newest -

Title: Little Girl Lost

Artist: Lisa Tillman Pritchard < https://www.etsy.com/shop/ltpartllc1/ , https://www.tiktok.com/@ltpartllc>Prior post

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2609&type=status

Lisa Tillman Pritchard post

https://aalbc.com/tc/search/?&q=lisa%20tillman%20pritchard&type=core_statuses_status&quick=1&author=richardmurray&search_and_or=and&sortby=newest -

Title: Hummingbird

Artist: Lisa Tillman Pritchard < https://www.etsy.com/shop/ltpartllc1/ , https://www.tiktok.com/@ltpartllc>Prior post

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2607&type=status

Lisa Tillman Pritchard post

https://aalbc.com/tc/search/?&q=lisa%20tillman%20pritchard&type=core_statuses_status&quick=1&author=richardmurray&search_and_or=and&sortby=newest -

Unofficial Title: Wisest Dreams

Artist: GDbee < https://gdbee.store/ > aka Prinnay

Prior posthttps://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2605&type=status

-

Title: Honey

Artist: Lisa Tillman Pritchard < https://www.etsy.com/shop/ltpartllc1/ , https://www.tiktok.com/@ltpartllc>Prior post

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2604&type=status

Lisa Tillman Pritchard post

https://aalbc.com/tc/search/?&q=lisa%20tillman%20pritchard&type=core_statuses_status&quick=1&author=richardmurray&search_and_or=and&sortby=newest -

Title: I Can Stand The Rain

Artist: shawn alleyne < Pyroglyphics Studio > OR < https://www.deviantart.com/pyroglyphics1 >Prior post

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2603&type=status

Shawn Alleyne post

https://aalbc.com/tc/search/?q=shawn&quick=1&type=core_statuses_status&updated_after=any&sortby=newest -

Unofficial Title: I dream of

Artist: GDbee < https://gdbee.store/ > aka Prinnay

Prior posthttps://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2587&type=status

-

Title: Baby Love

Artist: Lisa Tillman Pritchard < https://www.etsy.com/shop/ltpartllc1/ , https://www.tiktok.com/@ltpartllc>Prior post

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2588&type=status

Lisa Tillman Pritchard post

https://aalbc.com/tc/search/?&q=lisa%20tillman%20pritchard&type=core_statuses_status&quick=1&author=richardmurray&search_and_or=and&sortby=newest -

Title: aizan masked

Artist: shawn alleyne < Pyroglyphics Studio > OR < https://www.deviantart.com/pyroglyphics1 >Prior post

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2584&type=status

Shawn Alleyne post

https://aalbc.com/tc/search/?q=shawn&quick=1&type=core_statuses_status&updated_after=any&sortby=newest -

MY THOUGHTS AND THE ARTICLE

well i read the article, the argument by tyree is dysfunctional, the book was written in 2001, tyree admits the strategem would had been successful in 2010, so... saying it isn't how the industry operates in 2024 is dysfunctional. This is about a moment in the usa, this is not meant to be how the usa was before or after, but this was a real scenario. I wonder why everett had nothing to say. And the argument from some blacks against "urban lit" is no different than italians against italian mob movies . having people look like you represented in a way you don't like doesn't define you, but doesn't make it unreal. Some black people were and are step and fetchit's this doesn't mean I am or any other black person is one of them. Cord Jefferson's question shows he is either ignorant of black history or in denial about black experiences in the usa. For anyone who reads up to this point, let me say something that it seems isn't common knowledge in the usa. Most black people in the usa have always been unhappy or miserable, always. Yes from the colonial times to now a minority in the black populace in the usa has been happy. But, an overwhelming majoirty 95% to 75% of black people in the usa have been terrorized by whites in the usa or by the system of government in the usa designed or ruled by whites. I don't see how anyone black, non black or other can not accept that simple truth. Yes, obama exist, yes, michelle obama exist, yes oprah and the william sisters and lebron james exists. Ok most black people in the usa are miserable, are in pain, are unhappy, have dealt with trauma and they come from a centuries line of black people who felt worse. Said negativities are not the only things we have to offer to culture and have never been the only things. We made negro spirituals that uplift people today before the usa was founded. we made lues music that is utilized in so many asian animated works to characterize strong thoughtful characters. we made jazz that is considered world music and one of the utmost signs of improvisation. Cord Jefferson suggested black people's stories of pain or suffering or anguish or anger are too large in quantity, are too present. what? We made brer rabbit, which was referred to in positive fantasy star trek to save a bunch of defenseless humanoids from corruptions in and out of the fantasy united nations institution called the federation , with earth itself as its usa .saundra and others in the article's great flaw is speaking of the now. They can't get out of the now in assessing the film. Many black people in the usa like to say , black folk need to forget the past, but does that mean we are to lie about it, or judge all only in the modern?

ARTICLE

Some urban lit authors see fiction in the Oscar-nominated ‘American Fiction’

BY HILLEL ITALIE

Updated 10:41 AM EST, March 5, 2024

NEW YORK (AP) — Omar Tyree, author of such urban lit narratives as “Flyy Girl” and “The Last Street Novel,” recently went to see the Oscar-nominated movie “American Fiction.”

“I loved the emotions of the family,” Tyree said of the comic drama starring best actor nominee Jeffrey Wright as the struggling author-academic Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, Leslie Uggams as his ailing mother and supporting actor nominee Sterling K. Brown as his troubled and unpredictable brother. “I love seeing how Monk tries to bring the family unit together and just seeing Black people trying to work things out.”

But when asked about the film’s featured storyline — Monk finds unexpected success when he publishes a crude novel under the assumed identity of ex-con Stagg R. Leigh — Tyree laughed and gave a nod to “creative license.”

“The whole idea that he’s going to sell a lot of books by keeping it raw, in real life it doesn’t work like that,” he said. “That kind of book would have been stronger in the early 2000s.”

“American Fiction,” nominated for a best picture Academy Award and in four other categories, was adapted from Percival Everett’s “Erasure,” a 2001 novel that came out when a genre alternately called “urban lit,” “urban fiction,” “street lit” or “hip-hop fiction” was peaking, especially among young Black readers. Novels like Sister Souljah’s “The Coldest Winter Ever,” Shannon Holmes’ “B-More Careful” and Teri Woods’ “True to the Game” were selling hundreds of thousands of copies while major publishers, who had initially ignored the genre, were offering large advances in search of the next hit.

The urban lit genre dates back at least to 1967, and the release of the memoir “Pimp,” written by Robert Maupin, who was in jail when he began writing under the name Iceberg Slim and built a large word-of-mouth following. He inspired another street lit pioneer, Donald Goines, author of the Kenyatta urban crime series and other works from the 1970s that influenced such hip-hop stars as Tupac Shakur, who would famously declare, “Machiavelli was my tutor, Donald Goines my father figure.”

Urban lit is still around, but no new releases approach the heights of 20 years ago. According to Circana, which tracks around 85% of the print retail market, the genre sold around 380,000 copies in 2023, far less than the total sales for “The Coldest Winter Ever.” Many leading urban lit authors these days are either independently published — among them Black Lavish and Mz. Lady P — or released through Kensington Publishing Corp., which still has cut back over the past decade.

“At one point, the majority of the books on our list that were written by Black authors would have been categorized as urban or street lit,” says Vida Engstrand, Kensington’s director of communications. Because of changes in the “retail landscape and reader interest,” Kensington now offers a much broader selection, with “very few front list titles that fall squarely in the category of urban lit,” she says.

Everett, an award-winning author whose novels include “The Trees” and the upcoming “James,” was unavailable for comment, his publisher said.

Monk is inspired to write his pseudonymous book after looking through a bestseller titled “We’s Lives In Da Ghetto” and reading such sentences as “Momma says I be the ’sponsible one and tell me that I gots to hold thing togever while she at work clean dem white people’s house.” After failing to catch on as a literary author, he is offered a six-figure book deal and seven-figure movie deal for his profanely titled novel.

Stagg R. Leigh is praised by critics and even wins a prestigious literary prize. But few were calling Teri Woods or Shannon Holmes likely Pulitzer winners. The publishing community debated whether urban lit should be condemned for reinforcing stereotypes about Black life — stereotypes parodied by Everett in his novel — or welcomed for its blunt portraits of crime and poverty and for attracting new audiences.

“I’ve heard a lot of people within the Black community who have that viewpoint, that urban lit doesn’t reflect all of us,” says author Porscha Sterling. “And while it’s important to show the Black community in multiple ways, I do think it’s important to have a well-rounded view that includes everyone.”

“In my opinion, it was wrong to characterize these books as different from other Black literature,” says Malaika Adero, an author, agent and executive editor for AUWA, a Macmillan imprint led by Questlove. “We’ve had all kinds of classic books that dealt with the underground economy and the ghetto and weren’t classified as hip-hop lit.”

Monk’s novel has some parallels to a bestseller from the 1990s, Sapphire’s “Push,” an acclaimed and controversial novel about a pregnant teen from Harlem that begins in broken English, but becomes more traditional as the girl learns to read and write. At the time, Sapphire (a pen name for Ramona Lofton) was a little-known poet who received a large advance and attracted the interest of Hollywood. The book became the Oscar-winning movie “Precious.”

“American Fiction” director Cord Jefferson, nominated for best adapted screenplay, has said that reading “Erasure” reminded him of conversations he had with friends over the years.

“Why are we always writing about misery and trauma and violence and pain inflicted on Blacks? Why is this what people expect from us? Why is this the only thing we have to offer to culture?” Jefferson often wondered, he told The Associated Press last fall.

One urban lit author, Saundra, said she found “American Fiction” funny, but “a tad bit overdramatized,” adding she doubted a novel like the one Monk wrote would be so welcomed now. Sterling, whose novels include the series “Gangland” and “Bad Boys Do It Better,” said she identified with Monk’s frustration at not being understood and recognized, but also said the satire in “American Fiction” left her feeling “misunderstood”

“I don’t know any people who write like that in the urban lit genre,” she said.

Author K’Wan Foye, known as K’Wan, says he related well to the movie, even if it was “poking fun” at urban lit. He remembers being encouraged 20 years ago to write “something really ghetto,” what became his popular “Hood Rat” series, and showing up for a meeting at St. Martin’s Press wearing a Biggie Smalls-style suit.

“They thought it was some kind of persona, the way Stagg R. Leigh is in the movie,” K’Wan said. “And I was like, ‘No, this is who I am.’”

If “Erasure” had been published now, the protagonist would likely have chosen a different kind of book to parody the commercial market, authors and publishers say. Tyree thinks he would have been writing nonfiction, maybe working on a celebrity confessional like Jada Pinkett Smith’s “Worthy.” Shawanda Williams, who oversees the Black Odyssey imprint of Kensington, cites the 2022 bestseller “The Other Black Girl,” the surreal tale of a Black editorial assistant at a publishing house.

Saundra, whose novels include “Hustler’s Queen” and “It Ain’t About the Revenge,” says the urban lit market has faded enough that she’s trying a different kind of book. In 2025, Kensington will publish “The Treacherous Wife,” which she calls “domestic suspense.”

“Times are changing,” she says, “and I think readers are looking for suspense, something everyone can relate to.”

URL

-

Can I Use AI To Make Models For 3D Printing?

By Caleb Kraft

With all the hubbub around generative AI, it isn’t a stretch to start wondering in what new areas of making we might see this stuff proliferate. You can easily have ChatGPT write text for you or analyze your writing. You can instruct Midjourney, Dall-E, and other image generators to draw highly detailed, pixel-perfect creations in a variety of styles. What about 3D printing though? Can you type into a text box and obtain the perfect custom 3D printable model? Right now the answer is: kind of. However, in the very near future, that answer might be a resounding yes.

As of winter 2023–24, there really aren’t any systems advertised with the intent of 3D printing, so I’ll talk about the general concept of text to 3D model. This goal was out of reach a year ago when we published our guide to “Generative AI for Makers” (Make: Volume 84). In the short time since, the landscape of AI has been changing extremely fast and now we have a few different options for playing with text-prompted 3D model generators.

Ultimately, these tools are primarily focused on video game assets, so there are issues with 3D printing. While they do technically work, what you’ll see is that the current generation of AI model generators relies on the color layer to convey many details that simply will not exist when you 3D print. This means your print may be blobby, lacking details, or even oddly formed.

There are a few places where you can try this kind of thing, such as 3DFY.ai, Sloyd, Masterpiece X, and Luma AI. Since Luma is free and easy, I tried it. [ https://lumalabs.ai/ ]

Text Prompt to 3D Model

In Figure A you can see the results of the prompt “cute toad, pixar style, studio ghibli, fat.” (Don’t judge me, I know what I like.) The textured version looks OK from certain angles, but we can see the feet and belly have some issues (Figure B), and fine detail is lacking (Figure C).

3D Model to 3D Print

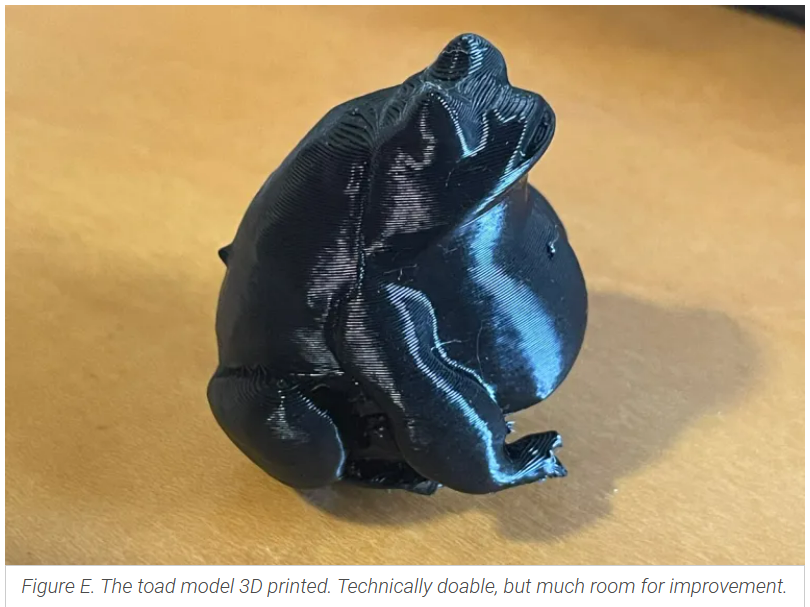

I had to convert the GLB file that was output by Luma AI to an STL file using Blender (Figure E),

but aside from that, it was ready to print. What you see in Figure is the result of a successful print from my Bambu X1 Carbon.While we can now say that we have used AI to generate a 3D printable model, we can also see that the geometry around the belly is very messed up. Printing it this way resulted in trapped supports that caused a mess when trying to remove them. I could bring this into modeling software and rebuild the feet and belly but at that point, with those skills, what do I need the AI for in the first place?

We’ve already seen 2D AI generative tools built into laser cutter software such as the xTool Creative Space. As these 3D tools improve, I can envision a near future where this kind of AI is built into slicers. Very soon you might just open your slicer, tell it what object you want, pick the best result, and hit Print!

This article first appeared in Make: Volume 88.

URL

Toy Inventor’s Notebook: Fun With Pop-Up Stamps

By Bob KnetzgerEven in an age of emails and texts, stamp collecting is still a favorite hobby of adults and kids. You can explore and learn about lots of things: geography, history … and toys.

There are lots of U.S. postage stamps that commemorate classic toys, and some novelty stamps are toy-like and fun in themselves!

This 2012 stamp from the Netherlands (below) was made to commemorate a Children’s Book Fair. This gummed stamp is a working pop-up toy. The cleverly engineered three-layer design has a top layer with the stamp graphics, a middle layer with a “sled” between two side guides, and a base layer. When pulled, the sled slides along, bending and folding a flap, which pops up revealing a cut-out shape. When pushed, the stamp goes flat again.

The latest toyetic stamp design is this sheet of “Message Monsters” from the USPS. They’re real “Forever” postage stamps but with a fun gimmick: the border of the peel-and-stick sheet is filled with extra stickers of hats, talking balloons, hearts and stars. Use the silly monster themed stamps on your mail, then add the extra stickers to make your own silly monster designs!

(Tip to parents of little kids: cut the fun “free” stickers off from the sheet of stamps — before they use up the expensive stamps on non-mail!)

You can make your own pop-up stamp like I did. I used a USPS commemorative stamp of a Hot Wheels car on some heavy paper.

Project Steps

MAKE A POP UP STAMP

First, choose which part of your image you’ll make “pop up.” With a sharp hobby knife cut two slits to make a flap, then cut around your pop-up shape. Gently score on the fold lines with a nail or hard pencil. For best pop-up effect, the middle fold line should be centered between the other two folds.

Cut out a sled and two side guides from more heavy paper. Make the sled a little wider than the width of the flap and cut two slits to make a little pull tab. Use double-backed tape or glue to fasten the guides onto the base so the sled slides smoothly between them.

Then tape the guides to the top and use a tiny strip of tape to fasten the flap to the very end of the sled. Cut and glue a matching tab from the stamp to cover the sled tab. Lastly, trim all three layers to a neat, final size.

You can make this sliding pop-up design with any size printed image: greeting card, photograph, drawing. Go wherever it leads you!

CONCLUSION

Find more fun novelty stamps with the Exploring Stamps YouTube channel.

URL

https://makezine.com/projects/toy-inventors-notebook-fun-with-pop-up-stamps/

-

impromptu sarah vaughan + sammy davis jr

Eartha Kitt Candid

-

A Day With The Master

stageplay

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/1025934041

poetry only

poetry

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/1025937253

illustration

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/A-DAY-WITH-THE-MASTER-graphic-from-Richard-Murray-1025928365The Settlement

StagePlay

COMING SOON

Haiku , theme frog

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/1025939467

Illustration

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/The-Settlement-graphic-from-Richard-Murray-1025929540Loose Dirt

Stageplay

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/1025941727

Illustration

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/LOOSE-DIRT-graphic-from-Richard-Murray-v2-1025930195We Left On The 11th ,Hope To Come Back On The 12th

Stageplay

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/1025945711

Illustration

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/Steel-Gifts-graphic-from-Richard-Murray-1025931263The Journey of Sofie Wakten to become a witch

Stageplay

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/1025949171

Illustration

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/DArk-Academia-photomanipulation-inspired-by-dark-s-1016036682 -

Artist: Mary Ann Ozurumba - marianas_art - < https://www.instagram.com/marianas_art >

Location: @the_matrix_gallery in Abuja, Nigeria < https://www.instagram.com/the_matrix_gallery/ >

Art Team/organizers: @experience_orange < https://www.instagram.com/experience_orange/ >her time at the gallery showing

-

Weed Gone Wild: 34 Cannabis Shops — But Just One Licensed — on the Lower East Side

New York’s marijuana legalization was supposed to bring order and justice to the market. Instead, one year later, it’s created a confusing potpourri of vendors.

BY ROSALIND ADAMS

JAN. 5, 2024, 6:00 A.M.

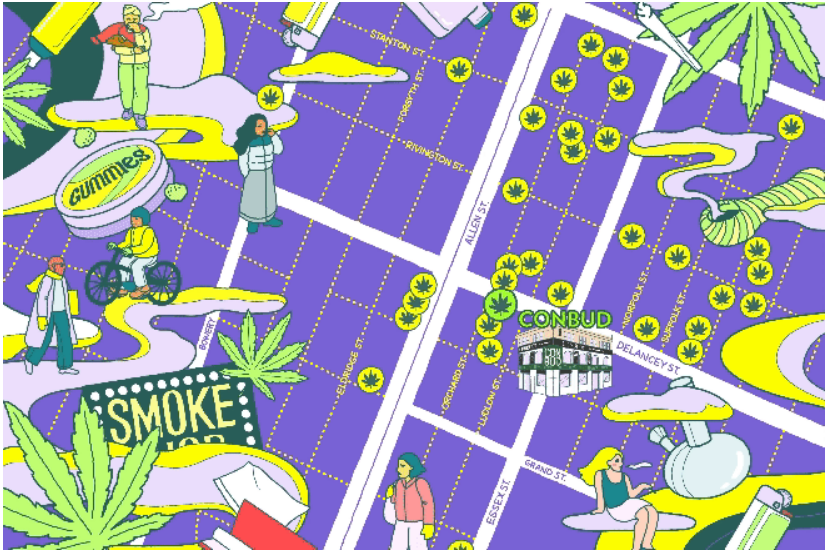

A map shows unlicensed Lower East Side cannabis shops near state sanctioned smoke shop Conbud. Credit: Illustration by Naomi Otsu

This article is a collaboration between New York Magazine and THE CITY.

On a recent Friday afternoon, a line of people wrapped around a corner of Delancey Street waiting for a turn to get into Conbud, one of the city’s 15 legal weed dispensaries. It’s the kind of scene New York State lawmakers imagined would be commonplace when they legalized cannabis in March 2021: customers neatly queuing up at a limited number of suppliers.

But instead such crowds are a rarity outside Conbud, and this particular one wasn’t even there for the weed. People were there to see Mike Tyson, the boxer, who grinned and flexed with fans inside to promote the New York launch of his cannabis brand.

On line, I met Vinay, 23, who had invited a group of his college buddies to the event. “My roommate sent me the email, and my friends are in town, so why not?” Vinay told me. “We love weed, and Mike Tyson is cool,” one of his friends interjected.

While we chatted, dispensary staff moved through the line with iPads to take orders (a purchase was required to snap a photo with Tyson). Vinay told me he had never been to Conbud before. He said he usually bought weed from one of the smoke shops a couple blocks away on Clinton Street. None of those are licensed to sell cannabis products, though. When I mentioned this, Vinay shrugged.

“I guess if I knew it was illegal, I wouldn’t go, but you don’t realize,” he said.

There are, in fact, only 43 legal retailers across the state, including delivery operations — and they are all run by people impacted by cannabis charges. When lawmakers legalized pot, they intended to give those harmed by prohibition a head start in the market. But a year after the first legal store debuted near Astor Place, the pace of licensed dispensary openings has been painstakingly slow.

Just to open their doors, legal dispensaries had to overcome a gamut of regulatory hurdles that came with a steep price tag. Anthony Crapanzano, who has a dispensary license in Staten Island, said he has racked up about $1.6 million in expenses so far, including $200,000 in legal fees, and is still not open. Coss Marte, the owner of Conbud, said he’s spent more than $1 million getting ready to open.

Once in business, state-approved weed shops can only carry products cultivated by New York farmers and are subject to strict regulations on how they market their goods. Neon colors, bubble letters, and colloquial references to cannabis itself are barred from store advertisements. Everything must be tested — and taxed.

While the cannabis-impacted entrepreneurs waded through Albany’s new marijuana bureaucracy, an estimated thousands of unlicensed smoke shops popped up in New York City. Because there’s little oversight, the exact number remains unclear. Around Conbud alone, rival smoke shops and weed bodegas line the blocks, flouting the rules with their white fluorescent lights and bright signage that make them so instantly recognizable as cannabis stores with names like Zaza City and Smoke Kave.

These unlicensed shops can be cheap and easy to set up (some keep just a small amount of product in the store in case they’re raided). And unlike their legal counterparts, the unlicensed stores don’t pay state taxes on cannabis sales, which means their weed is often cheaper. Some of them try to get around the regulations by operating as private membership clubs where pot isn’t sold outright but “gifted” or held onto for a friendly patron. Others are bodegas that dedicate a small amount of shelf space to cannabis products alongside the usual offerings of pints of ice cream and cans of Arizona iced tea.

The rapid rise of unlicensed shops has alarmed lawmakers who are trying a number of solutions to deter them. This past February, the Manhattan DA sent out letters warning more than 400 smoke shops that they could be evicted for unlicensed activity. In June, the Office of Cannabis Management and the Tax Department began the first of hundreds of armed raids of shops around the state, seizing product and posting vibrant warning signs in store windows. The city has filed lawsuits against dozens of shops in Manhattan for allegedly selling cannabis to minors. The New York City sheriff, too, has been inspecting unlicensed shops and seizing their goods. While a few shops have shuttered, the sheer volume of stores is proving to be a difficult test of these efforts.

THE CITY and New York counted at least 33 stores selling cannabis within a few blocks of Conbud on the Lower East Side. We visited five of the stores in the neighborhood to learn more about how the weed market has developed a year after the first legal sale of cannabis in the state.

Conbud – The Sole Licensed Dispensary

Conbud, which finally opened in October, is the only licensed dispensary in the neighborhood so far. Owner Coss Marte, who has three felonies for dealing drugs, was awarded a special license back in April. But after a lawsuit challenged the legality of the license program, a court injunction prevented stores from opening for months. Marte’s plans for a summer launch were derailed. Meanwhile, he and other licensees were racking up expenses paying pricey New York rents for idle storefronts.

In the meantime, the delay gave unlicensed stores an opportunity to gain more of a foothold in the neighborhood, Marte acknowledges. “The market has already matured in the Lower East Side specifically. Some of the stores around here have already been open two or more years,” he told me. “Consumers are just thinking that this is what it is, not that the stores are illegal.”

Inside, the shop borrows a lot from Marte’s personal story: There are product displays reminiscent of the milk crates he used to sit on outside a bodega selling drugs. A full-screen television shows a loop of Marte at a local farm tending to cannabis plants that would soon be harvested and sold in the store, an employee told me. On one wall, the text of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery, is posted in bold letters. Conbud-brand T-shirts with the law’s text are available for sale, too. The effect is twofold: Marte is selling customers on the store’s cannabis products, like gummies marketed for sleep or energy and locally grown cannabis flower, but more broadly on the idea that legalization can be a form of reparation to those harmed by the war on drugs.

One of the most popular products is an ounce of Hudson Cannabis that’s grown upstate and runs for $185 — the best deal in the store but not as inexpensive as what some of the unlicensed shops offer.

A week before the Tyson event, Conbud threw a party to celebrate the launch of the Dr. Midtown brand, owned by a former legacy operator who goes by Nas. He told me he used to run a 1,200-person delivery route in Manhattan and was arrested in January 2021, right before the law changed. “I grew up in Queens, and it’s just been constant harassment,” he said. To see his brand now in stores, he added, “is exactly what we’ve been fighting for.” Promotional flyers for the party were printed with both Marte’s and Nas’s old mug shots along with the slogan “From Legacy to Legal.”

Part of the goal in hosting events like the one with Tyson and the launch party for Dr. Midtown is to educate people, Marte said. People living in the neighborhood see the long lines or hear the music and stop by to see what’s going on. That gives Marte an opportunity to explain that Conbud is the only legal cannabis store in the Lower East Side, he said.

“The more events we do, the more the community is aware that, ‘Hey, we’re here and we’re legal.’”

Flame Zone – A Shiny Smoke Shop

Shortly after Conbud opened in October, a flashy new smoke shop called Flame Zone Convenience appeared right across Delancey Street. The store employs several of the marketing techniques that legal stores are specifically prohibited from using. Its signage is written in a neon-green rounded bubble font. A sign advertised a grand-opening sale of an eighth of an ounce of weed for $20 (less than half what an eighth of Mike Tyson’s brand costs across the street), while another says the vape shop has the lowest prices around. If there was any doubt the store sold weed, there’s a towering inflatable joint just inside and a second one suspended from the ceiling.

Before Flame Zone opened, the business here was called Gee Vape and Smoke Shop. In February, Gee Vape was one of more than 400 stores the Manhattan DA warned in a letter could be evicted for selling cannabis. The store later closed. Flame Zone, according to the employee at the counter, is a different business from Gee Vape. “This is a new owner. She changed everything,” he told me.

While the shop may have a shiny new exterior, the property owner has been the same since 2007, city records show. Enforcement efforts have started to increasingly target landlords, not just the stores. But so far those measures have done little to deter a landlord from simply leasing the space to a new smoke shop. The volume of shops is simply too high.

In mid-November, shortly after Flame Zone opened, the Office of Cannabis Management and the New York State Tax Department raided the store. The two agencies are one part of the enforcement effort to curb the illegal shops. Last year, the state inspected 350 storefronts and seized more than $50 million worth of product, according to its latest figures LOOK BELOW. Though a pink slip from the raid is still posted in the door, it’s open for business.

Behind the counter, there are vape cartridges and pre-rolls branded with major California companies like Stiizy and Jungle Boys. House pre-roll joints are three for $20. When I ask the shopkeeper where the weed is from, he says, “Here, it’s in-house.” Only New York–grown weed is permitted in legal shops, and it remains illegal to transport cannabis across state lines. But for years California brands have faced allegations of “backdooring” their product to other states, and a number of websites sell counterfeit packaging from California brands down to a randomized serial number and QR code. That makes it hard for customers to know what they’re really buying.

Despite the bright lights and the low prices, the store still gets little foot traffic on a chilly December evening. In a half-hour or so, I see only one woman go into the store. She popped in while waiting for her order at Wingstop next door, she told me. When I asked what made her choose that particular store, she shrugged. “It’s just the closest one,” she said.

MetroBud – A Private Members Club

Owned by Joe and Jason Coello, two brothers from Queens, MetroBud on Allen Street operates as a private membership club. Blue velvet ropes guide customers to the entrance, and an employee checks IDs before letting anyone inside. The shop differentiates itself by encouraging people to stay awhile. Inside, two televisions loaded with video games are available to rent, and there are a few couches where you can just smoke and chill. MetroBud also hosts events like a weekly yoga class.

Joe Coello started planning to open the store as soon as legalization passed in March 2021, reasoning that a membership model was a way to get started without a state license. “We were trying to operate as above board as we could,” said Coello. “We were operating legally, as far as we were concerned.”

When the cannabis law passed, it included protections for people possessing weed as well as giving it away to their friends. Interpreting the latter to mean that they may legally “gift” weed to patrons or possess weed on behalf of members, cannabis membership clubs like MetroBud began popping up across the city. At one club I visited, customers pay for a photograph — and then are “gifted” cannabis in return.

There are no specific regulations that govern how the clubs operate because the distinction is not sanctioned by the state regulatory agency and there’s no specific license category for the model.

On many days, MetroBud seems to function like any other weed store. Daily membership is effectively free, so anyone with ID can walk in off the street and make a purchase. On a recent Saturday night, there was little foot traffic and just one customer inside fixated on playing Mortal Kombat. The store carries various branded MetroBud strains of weed from New York farmers as well as other brands. Prices are divided by tiers and at the low end can beat prices that legal shops like Conbud offer.

The membership-club interpretation of “gifting” hasn’t been tested in court, but last year, the Office of Cannabis Management sent out letters warning operators that running unlicensed shops could potentially jeopardize their ability to get a license in the future. The letters specifically stated that a membership-club model was not allowed.

Despite the state’s warnings, Coello still hopes to go legal and has applied twice for retail licenses since opening MetroBud. “It would be nice just to not have to look over our shoulder,” he said.

Meanwhile, Coello defends his business model — and the crop of unlicensed shops in the neighborhood. “I believe in a free market,” he said. “As long as they’re putting out products that are safe and don’t have heavy metals, mold, or pesticides in them, I don’t see a problem with it.”

Allen Convenient Exotic – Twice Raided

Walk down Allen between Delancey and Broome Streets, and you’ll find two more smoke shops near MetroBud: Green Apple Cannabis Club and Allen Convenient Exotic. Red, green, and purple lights from the trio of stores overwhelm passersby. As I stood outside on a recent evening, I watched a couple point to the fluorescent lights. “Why do all these places look so ugly?” one asked.

Cannabis was legalized just one year into the pandemic, as restaurants and retail shops were struggling to stay afloat. Some smoke shops have opened in place of establishments that stopped paying rent in the pandemic. The space occupied by Allen Convenient Exotic had been a smoke shop for years, selling items like vapes and glass pipes and cigarettes. But Green Apple Cannabis Club used to be a clothing store, and MetroBud was previously a pop-up space hosting events from brands including PornHub and Subway.

The three stores are an example of how ineffective state enforcement has been in curbing unlicensed sales. While Green Apple and Metrobud’s owners both say they’ve never had any major issues with state or local law enforcement, Allen Smoke Shop has a poster in the window with loud red letters: ILLICIT CANNABIS SEIZED. The store has been raided at least twice by state officials, according to the posted notices.

To allay any doubt that it still sold cannabis, the shop projects a roving image of the cannabis plant on the sidewalk outside.

Inside, there’s a wall of sodas and chips and even a small shelf of Bounty paper towels as in any other neighborhood bodega. Much more discreetly than in a place like MetroBud, the cannabis products like THC-laced edibles as well as “mushroom extract” gummies are confined to just a small section at the front counter. With a few cannabis-plant signs in the window and a bit of shelf space, the shop is an example of how easy it is for owners to add on a few products. When I snap a photo with my phone, it immediately catches the attention of the shopkeeper. “Hey, no photos. You can’t take a photo in here.” With the flip of a switch, the clear glass counter turned a frosted white, concealing the contents from view.

Dubai Cannabis Supply – Sued by NYC

I head over from Allen to Stanton Street, which has its own row of unlicensed shops selling cannabis. I pass by a few of them and head into Dubai Smoke, which the city sued in July, to see how it’s currently operating.

The complaint cited three instances in which the shop allegedly sold illegal psilocybin products. Created in the 1970s as a means to shutter undesirable businesses like places of prostitution, the nuisance-abatement law is one more tool the city has to curb illicit cannabis shops. In 2023, it filed at least 35 cases against smoke shops and their landlords for selling cannabis products to minors. Inspections are typically carried out by the NYPD, which documents at least three instances of the unlicensed activity before seeking a court order to close the store for one year. The city settled with Dubai in November on the condition that it would not sell unlicensed cannabis or tobacco products.

But a December visit shows that’s plainly not the case yet. Inside, the shop looks like the color palette of a Jojo Siwa concert. The walls are covered in rainbow graffiti, and under the glass cases there are glass tubes of pre-rolled joints for $20 labeled ZKITTLES. The man at the counter pulls out the tray of ones that come in flavors labeled Cotton Candy, Jungle Juice, and Froot Loops. A row of vape cartridges has options in lilac and teal and fuchsia. There are more California brands, like Stiizy gummies, on display here, too. None of these rainbow offerings would be allowable at the neighborhood’s one legal dispensary, Conbud.

Outside, I spot a group of what appear to be teen boys passing a joint among them. I nod to the joint and introduce myself as a reporter working on a story about cannabis shops in the neighborhood.

One tells me loudly they’re all 21 before laughing.

“Bro, no you’re not, no you’re not,” one of them shouts.

“Okay, yeah, we’re all 16.”

“I’m actually 35,” says a third. (I start to believe they are indeed 16.)

Dubai Smoke Shop wasn’t cited for selling to minors, but at least 34 other shops in Manhattan last year were, according to a review of nuisance-abatement complaints. This has been a rallying cry of lawmakers looking to shut down unlicensed shops with no oversight of its sales.

When I asked the teens where they liked to go for weed, they brushed me off. “I mean wherever they will sell to us, there’s only a few places around here,” one said.

“We’re not gonna tell you which ones.”

Article link

https://www.thecity.nyc/2024/01/05/weed-gone-wild-cannabis-lower-east-side/New York Fined Unlicensed Weed Shops More Than $25 Million — and Collected Almost None of That

Gov. Kathy Hochul has said she wants to shut down the illegal stores, but the lack of enforcement reveals just how hard that task will be.

BY ROSALIND ADAMS

FEB. 22, 2024, 5:00 A.M.The state has levied more than $25 million in fines against unlicensed smoke shops for selling cannabis products since last year, but so far only a minuscule percent of those fines have been collected by both the state Tax Department and the Office of Cannabis Management, THE CITY has learned.

The two agencies were granted greater authority last year to enforce the 2021 cannabis law and began joint raids against smoke shops for selling cannabis products without a license last summer. They levy and collect fines separately, however. Fines may be levied against individuals who operate the smoke shops or the business itself when it’s difficult to track down an owner.

The Office of Cannabis Management (OCM) said it has collected $22,500 in fines from unlicensed shops. The Department of Taxation and Finance has collected $0 in fines so far, said sources familiar with the state’s enforcement progress.

Last October, THE CITY reported that the state cannabis agency, citing a lack of resources, had paused the enforcement hearings that follow state agency raids on unlicensed shops. Lawyers for unlicensed shops told THE CITY at the time that they had received notices on behalf of their clients that the cases were being withdrawn. Meanwhile, the raids have continued.

But while OCM has withdrawn many cases, some shops and their operators have separately received letters separately from the tax department warning them of fines more than $150,000, according to notices obtained by THE CITY.

“Currently, the State is prioritizing shutting down illegal shops and seizing unlawful products,” said Aaron Ghitelman, a spokesperson for OCM. “While we recognize entities being fined have a right to due process, we are committed to working within the confines of the law to collect the fines once the legal process is complete.”

Fines levied by the tax department may be appealed, for example. And shops fined by the Office of Cannabis Management may be challenged in the administrative hearings the agency paused back in October, which lengthens the state’s timeline to collect the fines.

Ghitelman added that the state has seized tens of millions of dollars in illicit products as part of its enforcement measures. Gov. Kathy Hochul has repeatedly emphasized the amount of product seized in press releases about the progress of the raids.

The governor’s office and the state tax department declined to answer questions and deferred to the statement provided by OCM.

The dearth of fines collected so far highlights the challenge of enforcing the cannabis law in a state with a booming gray market.