|

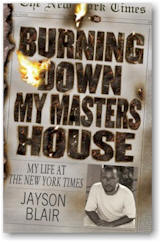

by Jayson Blair

ISBN: 193240726X |

His nails were grimy. He was unshaven. A thin layer of hair atop his head brushed some days ago for the first time in a while. A navy blue off-the-rack suit, too long for his limbs, draped from his body wrinkled as though he’d just awakened from a nap. A misfit of buttons lined the sleeve of his jacket. Two buttons in a row, then a broken one, then the crumb of a button holding on to a single piece of thread. A rayon or polyester or mixed blend shirt tried its best to camouflage the bulge leaning over a belt pulled too far through loops. A cardinal sin of fashion had been committed’black belt brown shoes. Worn over shoes. Shoes curling at the toe more suited for a ride on magic carpets. Grayish-greenish socks with the heel turned to the front fit like an accordion around his ankle. He shifted. Before doing so, I knew it would be there. Dry skin. Ash. The kind that embarrassed mothers.

I'd arrived thirty minutes prior to stake my claim on the front row. Moved to the second row so everyone could hear my question. I wanted all to hear. Wanted them to know I'd done my homework, that this inquiry would get to the heart of the matter. I would ask it with civility and compassion. Compliment him first for courage and candor. For coming out night after night in front of firing squads. Then I'd shoot. Hoping his Kevlar hadn’t grown too strong after numerous interviews. My question was timely, a development only one day prior. He couldn't have had time to prepare.

He walked by me’fifteen minutes before the start time. Prompt, I noted. Sincerity or part of the ploy, I wondered. I was reading another writer’s book. Held it up high as to show him that I was not reading his. Nor did I have an interest in buying it. Euphoria would have been him asking if I was getting a book and I would dart a harsh’wait a nonchalant, ’No’.

There were pictures and interviews so I knew to expect a small man. But he was beyond short. He was teetering on dwarfism. A sympathetic small. Like a boy I'd befriended in elementary a school. His name escapes, but I remember I'd taken to him because he was small. A stratosphere below me. Like this one here greeting people in the audience. Sir-ing and ma’m-ing them all with the most beautiful and beaming smile his cigarette and coffee stained teeth could gleam. He was in fact a slob.

I'd remembered while living on his website, there was an interview or perhaps it was in print. He’d talked about issues of self-esteem. How he was short and felt inadequate. Not sure if inadequate was the description he’d used, but it fits here. This struck me because I'd been thankful at that moment to have been born tall, despite my own feelings of being inadequate.

Why doesn't he have a make-over I thought, get new clothes, I wondered? The image of a modest living, was this part of the ploy? Why doesn't he get a nice haircut? Image and perception it all matters doesn't it?

A bookstore worker more concerned with leaving on time than the historical significance of this moment, said nothing more than. ’Without further adieu, Jayson Blair.’ I waited. Should we applaud? No one moved.

He thanked us. Obligations out of the way. The crowd was sparse. Twenty maybe. More Black men than I'd ever seen at a book signing. A man on the front row to my left. Rust colored thick glasses like my uncle had worn when we saw Hank Aaron play against Willie Mays. I watched him with raised eyes beneath the lowered brim of my cap. Spying really. He flipped the book, scribbling questions that I tried to decipher. Something written with alliteration that couldn't understand. No matter. As long as it was not my question. I'd raise my had first just in case.

Blair grabbed a microphone from a stand taller than he was. Said hello. Nothing amplified . His voice shaking as though this were the first of his firing squads. Cleared his throat once then again. Cigarettes I thought. The mic stole his opening thunder. Put it at aside and tired with little success to project an articulate polished voice. No accent, no drawl, no indication as to where he’d lived, his ethnicity even. Weak, at times faint, the voice explained what he’d do, how the program would proceed.

He tried to pierce me, I suppose. The first words, the first few seconds he looked at me. Directly at me. Through me. A gauntlet. Had instinct alerted him that I'd come to ask the question, the wounding one, the one he could not escape? I held strong. didn't blink, didn't shift. Arms folded, eyebrows lowered. Hurry, I thought. Get through this. Let me spit my question.

He read, spoke, explained. I heard, wondered, doubted. He giggled, exhaled, flinched. I listened, assumed, watched. His voice quivered. Rehearsed I thought. He cleared the throat again. Nerves, I presumed. He stumbled over words. didn't write them, I guessed.

The reading and discussion covered race in the media, his mental illness, and the hope to bring good out of the ordeal. Hurry. Get done. Open for questions. So he did.

My hand went up. My stomach churned they way the queasy burning hits before all big questions. Will you? Is it malignant? Wanna come up? I'd rehearsed the hand raising. Not too erect. don't shoot it up fast. Just two simple hinges. One at the shoulder and another at the elbow. Ninety degree angle with bicep and forearm. Ambitious, but not anxious. He pointed to me. Passed me the mic. A bookstore worker who’d simply forgotten to press the on button had come back two minutes into his speech.

He gave me the mic. It was as though he was stuffing it in my face. Daring me to ask a question. Challenging me to trump even the toughest questions he’d faced. And then I was inadequate in that moment. Like I had been before. Who was I? I'd lied. I'd mislead. I'd deceived. I'd done wrong. Who was I to arrive early and order the worst Caramel Macchiato in the history of Starbucks and sip it like I was God’s consigliore.

But I grabbed the mic from his small pointy fingers. Nails of different shapes and sizes. I asked. Complimented first the way I'd seen the setup performed on interviews with headlines scrolling across the bottom of the screen. And he knew it. He knew the setup. Because he’d done the setup for a living. His eyes waited. He didn't move during my kowtowing. Not a nod or a thank you or a mmm-hmm. He waited, strapping on the Kevlar and I shot him.

Asked about an error/lie/mistake/oversight/inaccuracy/half-truth in his book. My tone remained civil. Let the words work. don't inflect the voice. Let it all roll off. Quote the source. Site the page in the book. My head was warming. An adversarial fever was blistering. Just one more sentence and I'd be done. don't let the childhood stutter emerge. The one cousins ridiculed. The one that instantly discredits your intelligence. The one that tells people, you're a bumbling idiot. Narrowly, I escaped. Got to the part of my rehearsed question where the source was quoted, names were called out. Suddenly, he reacted. He nodded, mm-hmmed, began answering before I finished. He’d done the same thing on NBC with the woman. Talked over her, but she didn't stop. Of course she didn't. Nor would I. I plowed through the question. Felt the stutter rumbling. Forged on hoping it would suppress. And then he crouched from the chair. He was standing. He reached for the mic. Was he trying to cut me off? Trying to silence my source, muffle my names, mute my question? He made a motion towards me. I should have sat in the back row. He never could have gotten this close to me. He reached while asking to respond. I'd made it. Asked him to ’Talk about that briefly.’

So it began. He explained that it was a mistake, that it would be corrected. That to mistakenly mention a way a man’s mother had died was not something intentional. That there were other mistakes in the books that would be corrected. He didn't run or dodge. He, in fact, took the advice of Edgar A.Guest. ’When the worst is bound to happen ’spite of all that you can do, running from it will not save you see it through.’

Then the proclamation ’I'll answer anything,’ he said. He did. Questions like jack hammers. Unrehearsed or researched like mine. Why’d you do it? How'd you get caught? Were you not a good liar? What’s it like for Blacks in the media? What’s next for you?

It became real. It became convincing when the short, too-long-suit-wearing man became a naked giant. He was here, answering the tough questions. Rick Bragg was not. He was here being attacked (and rightly so) Patricia Smith of the Boston Globe was not. Here he was getting judged unlike Jack Kelley of the USA Today. He was here taking the beating unlike Khalil Abdullah of the Macon Telegraph.

Still, he’s been bastardized. For doing what he did to the newspaper, to journalists, to Black journalists, to future Black journalists. He’s no one’s hero, I thought. Until someone in the back of the room posed the question which changed the program.

’I have a question. My name is Fran. Fran’Blair. I’m Jason’s mother. First I'd like to say, Happy Birthday, Jay.’ Ice cycles dropped as the small crowd smiled and gave the obligatory wish. ’Jay my question is’’

wasn't relevant, for he said he had no answer. But my hand shot up. Broke the rules. Shot straight up, erect. No angle. No hinges. He passed the mic to me again, this time with a smile.

Off the cuff I flowed. Damn the stuttering. ’This is an amazing opportunity to have Jayson here with his mother—’

’And father,’ he added.

’I'd like to know, Mother Blair, what has been the most difficult thing for you during this entire ordeal. Because I know that regardless as to what Jayson is or what he has become, at the end of the he’s still your baby. What’s been the hardest thing for you?’

Before she’d answered, Blair had been transformed right before us. A staff becoming a snake. A river parting. Five thousand fed. It was his mother. Here from Virginia on the anniversary of the day he’d entered the world. A humanizing moment for even the most villainous of monsters. The boy’s mother was there for God’s sake. How can you beat up a short kid in front of his mother? It cannot be done.

A woman with white pearly teeth, and a perfect facial landscape of make up, dressed in a perfect blend of autumn hues stood before the crowd as though she’d been waiting in line or expecting that her number would hit today. A woman from which truth and integrity seemed to drip from her pores.

She explained that how since her son was diagnosed with a bipolar disorder, she was grateful he was getting medication and he had the disease under control. She expressed regret that perhaps she hadn’t caught it earlier. Maybe there was something she missed. But of the toughest part she said simply, ’Contacting my child everyday to see if he was still alive.’

The program ended with reflections and comments from the mother. A round of applause barely audible a few shelves over. Some of Blair’s closing wishes were that people could learn from all of this. (Other than securing a three-figure book deal from plagiarism.) What would we possibly learn from this I wondered? I was intent on believing that every Black journalist from this point forward will be scrutinized however subtle. Then it was clear, there will be no need for scrutiny. For the future Black journalist, those fledglings writing for high school rags across the country, hell the world. They will forever be warned about Jayson Blair. His name will be etched in young minds like some type of journalistic boogey man. Hence begins the onslaught of self-scrutiny for the future journalists of the world.

Though his appearance is a bit rough, his dress vagabond, it does not take a way from his prose which is in a word beautiful. If Blair’s intent for this book tour was to bamboozle his speech with puppy dogs eyes and a don't-beat-me-no-mo’ grin just so people will by a copy of his book; he has failed. For I promised myself I would not buy one. I bought two.