Kathryn M. Johnson

Biography

Kathryn Magnolia Johnson, born during the “Jim Crow Era,” was a woman of color, one of many unsung heroes of a budding civil rights movement. Kathryn was a champion for literacy, education and social justice in colored communities throughout the country and the world. Kathryn’s journey takes us from Darke County, Ohio, where she was born, to New Paris, Ohio where she experienced the “colorline,” and the reality of racism, to Wilberforce University where she was inspired, through the horrors of the Argenta Race Riot, her experience as the first field agent for the NAACP, her service to the colored troops in WWI France and her travels throughout the United States selling her “Two Foot Shelf of Negro Literature.”

The Two Foot Shelf of Negro Literature tells the story of Kathryn Magnolia Johnson, a multiracial champion for Negro Literacy, opportunity and justice. Her story takes place during the Jim Crow era, from post reconstruction to the beginning of the modern civil rights era in the 1950’s.

The Two Foot Shelf of Negro Literature tells the story of Kathryn Magnolia Johnson, a multiracial champion for Negro Literacy, opportunity and justice. Her story takes place during the Jim Crow era, from post reconstruction to the beginning of the modern civil rights era in the 1950’s.

Kathryn’s awakening to the significance of skin color occurs at an early age, when a few years after Kathryn’s father dies, her mother remarries a man of a much darker complexion, which resulted in all but one of her seven brothers and sisters to leave home. Kathryn realizes for the first time that there is a color divide not only between black and white people but within the black community itself, “the color line.”

At age eleven Kathryn contends with racial isolation when she is enrolled in the New Paris, Ohio school system as the only colored child in the grammar school. Her family is ignored, and she is shunned on the playground causing her to feel invisible and unwanted.

Kathryn graduates is accepted at New Paris High School, but a white parent opposes her attendance, saying, “there are no jobs in New Paris for a color girl with a high school diploma.” Kathryn realizes that in the minds of white people, education is not important for people of color.

Kathryn notices the derogatory comments about people of color in her text books and starts to wonder why black people are treated so badly. Her concern for racial injustice take off at this point in her young life and she starts looking for answers Kathryn attains the highest-grade point average in her graduating class but is not given the scholarship award that goes with that honor. The scholarship goes to a white student that Kathryn had tutored throughout the school year.

Kathryn attends Wilberforce University and finds herself in an environment of acceptance, void of racism, she is no longer invisible. She graduates from the Normal school two-year teaching program and finds a teaching position in the Darke County school system, the town where she was born.

Kathryn receives a State grant to return to Wilberforce and complete her bachelor’s degree. After attaining her bachelor’s in science, she secures a teaching position in Elizabeth City, North Carolina. She is hesitant to go because she has never been in the deep south, but her mother convinces her to take the position.

Kathryn finds out that her mother is ill with cancer. She researches treatments but is told that only surgery will help.

Kathryn returns home from Elizabeth City and finds out that her Mother’s cancer has worsened. Kathryn takes a leave of absence from the school in Elizabeth City.

A friend and professor at Wilberforce offers Kathryn the position of Dean of Women at Shorter College in Little Rock Arkansas, Kathryn accepts. Three weeks after taking the position, the Argenta Race Riot occurs. For the first time Kathryn is faced with the ugly violence of racism.

Kathryn finishes her term at Shorter College, and moves to Kansas City, Kansas, for a teaching position at Sumner High School, when House Bill 802 passes, segregating Kansas City high schools.

The new principal of Sumner is accused of inappropriate sexual advances toward the teenage Sumner High girls. Kathryn finds out and complains to the school board. Kathryn losses her teaching position because of her complaint.

Kathryn realizes that to secure justice for black people, an organization of talented people willing to sacrifice their all is needed. Receiving the first edition of the NAACP’s Crisis magazine, Kathryn has finally found that organization in the NAACP, and starts selling the Crisis magazine.

Even though there is a possibility of reprisal from the KKK and other white supremacist groups, Kathryn travels around the south speaking at churches and schools, organizing NAACP branches. Kathryn’s success is recognized by leaders of the organization and this recognition propels Kathryn to further expand her literacy and social activism.

The U.S. enters WWI in April 1917. Kathryn wanting to do her part for the war effort, she volunteers with the YWCA, and is called to serve the colored troops in WWI France.

Kathryn sets up libraries and schools for the colored troops in France, and fights attempts to bring Jim Crowism to France. She is recognized for her work by the Armed services.

Fourteen months later, Kathryn returns to the US from France, and is faced with the resurgence of the movie,” Birth of a Nation.” She is asked by the NAACP to march in protest to its showing at the Capital theater in New York.

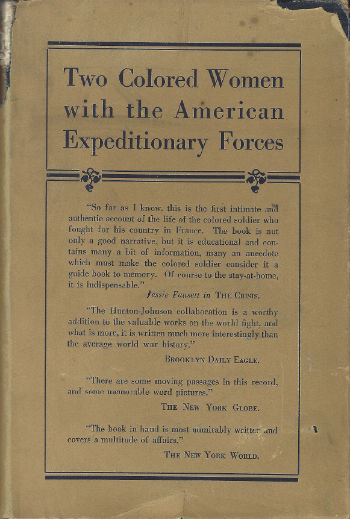

Kathryn in collaboration with Addie Hunton writes about their experience in WWI France and the experiences, discrimination and treatment of the colored troops. They find resistance from book publishers, concerned that the disclosures might spark race riots.

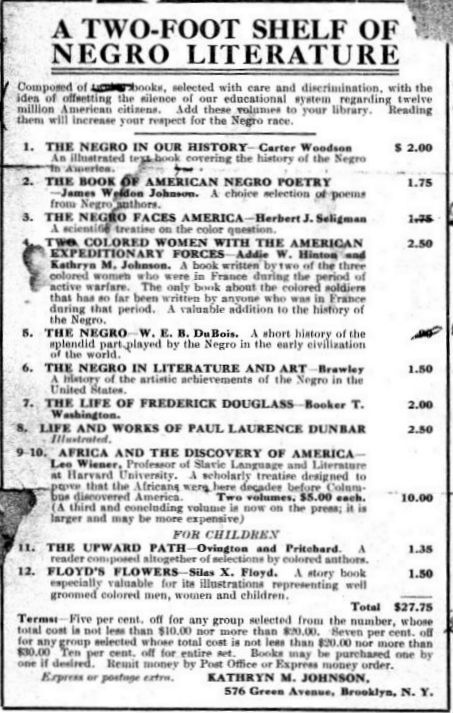

Her activism heightens and is directed at improving literacy and education in the colored community. She collects fourteen books written by Negro authors and in her Model T Ford, sets out to deliver those books to colored communities, churches, schools and libraries around the country. Kathryn calls her the collection, “The Two Foot Shelf of Negro Literature.” Starting in the northeast, Kathryn goes south and west visiting colored communities where books were unavailable due to Plessy vs. Ferguson, or separate but equal segregation. Witnessing poor schools, education and jobs for the colored communities, Kathryn considers socio-political activism.

In 1932, after several years of travel back and forth across the country, fatigued, the miles of driving taking a toll on her health, Kathryn settles in Chicago and helps Ezella Mathis Carter start homes for colored girls seeking an education.

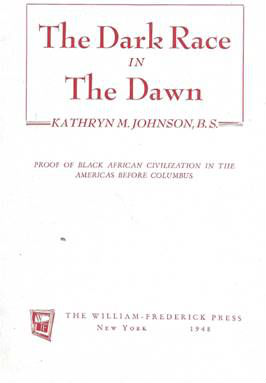

Kathryn’s activism extends to Africa, when the King of Swaziland asked her to chronicle the takeover of his land by the British. Having to clandestinely receive documents, Kathryn agrees to take on the task.

Kathryn’s brother, Dr. Joseph Johnson, named the first minister to Liberia, makes her aware of the abject poverty in that nation. She raises money to provide clothing and medical supplies.

During the Spanish Civil War, Kathryn along with Paul Robeson, Richard Wright and other notable black men and women raises money to send an ambulance and medical supplies to the poor oppressed people of Spain.

In 1934 Mme. Ezella Mathis Carter dies and Kathryn remains in the home at 4509 S. Prairie, Chicago, continuing the social services started by her friend and colleague, opening the home to colored women in need.

Kathryn’s political activism begins in Chicago. Kathryn continues to speak against racial injustice and encourage greater interaction between the black and white communities.

In 1940, Kathryn runs on the Republican ticket for representative in the first Congressional District of Illinois. She doesn’t win but the contest makes her a vanguard for women in politics.

In 1945 as a member of the, Council to Make Permanent the FEPC.” (Fair Employment Practice Committee), Kathryn meets with members of the U.S. Congress.

After many years of travel enlightening both black and white communities of the accomplishments of black people, after many speeches, books, championing literacy, social and political activism, Kathryn gives her last speech at the Lincoln memorial. She died a year later on November 13, 1954.

By Armand A. Gonzalzles MD FAAP