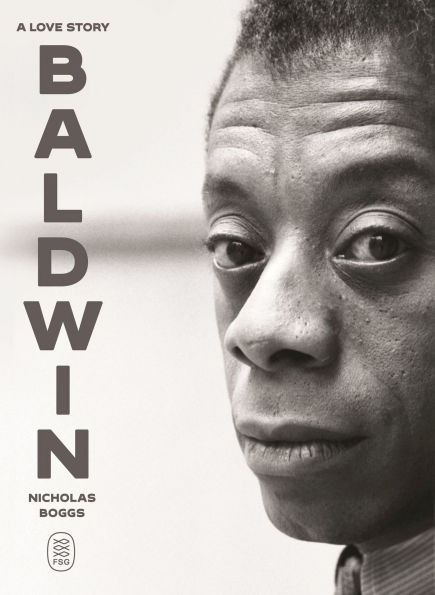

Book Review: Baldwin: A Love Story

Reviewed by:

Robert FlemingLong before I met James Baldwin’s friend Vertamae Grosvenor, I was a preteen Black boy who had read the writer’s bold novel Go Tell It on the Mountain, and it rocked my world. As a kid raised in the raucous atmosphere of a Baptist church, I recognized all the themes and characters struggling for salvation and renewal. My generation, and some church elders who read, understood the “thin cullud boy” from Harlem knew of what he wrote, without compromise and pretense.

Here, Nicholas Boggs has written a supremely detailed and intimately penned biography of the scribe, born in 1924, who internally battled his sexuality and his looks, especially “his frog eyes.” One thing that sets Baldwin apart was his mental brilliance and the ability to put his stunning concepts into words. His sixth-grade teacher, Orilla “Bill” Miller, took the shy youth under her wing, exposing him to cultural delights outside of his community, including the Orson Welles’s pioneering all-Black production of Macbeth. His new mentor stepped in as family supporter, providing food, when his father lost his job. Another mentor, the controversial Harlem Renaissance poet Countee Cullen, endorsed Baldwin in his application to the elite DeWitt Clinton. Baldwin seized the opportunity as he joined the staff of the school’s prime literary magazine, where many of the writers would later make their mark on the national culture.

While Cullen considered the teen as intellectually precocious and sexually confused, his young charge would emerge as a vocal advocate for queer Black writers, speaking truth to power yet maintaining his authentic self. The gifted lad attracted a series of mentors and influential friends who largely protected him from society’s harsh penalties and allowed him to proceed toward literary stardom. One such handler, famed painter Beauford Delaney, opened the door to the city’s queer, multiracial world, where he made friends and associates knowing the ropes of the art universe. They became close friends, with Baldwin absorbing blues rhythms, allure of an artistic community, and the glitter of celebrity.

Internally, the writer was at war with himself, anxious, afraid of losing himself to the power of the lusty attraction of both intellectual and sensuous temptations, willfully corrupted by the legions of one-night stands with the purpose of carnal relief. The artistic Greenwich Village because was a cupid trap, even though he found “love” with Eugene Worth, a young socialist. He concluded, “And, racially, the Village was vicious, partly because of the natives, largely because of tourists, and absolutely because of the cops.” In 1946, Worth killed himself and the writer blamed himself.

“Love does not begin or end the way we seem to think it does,” Baldwin reasoned. “Love is a battle, love is a war; love is growing up.”

Boggs emphasized this internal psychological conflict, highlighting the writer’s theory that “all art is a kind of confession.” At times, this mammoth biography permits the reader to listen in on key private thoughts and desires of the man, without the judgement of a moralist. From the autobiographical first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain to Giovanni’s Room through Another Country, the biographer details how Baldwin’s literary fame was intertwined with his intimate personal experiences.

America remained a painfully harrowing cultural puzzle for Baldwin. When the New York literary world took notice of him, he earned the Rosenwald Fellowship following a winning series of book reviews, essays, and short stories. When he went to Paris in 1948, Richard Wright assisted him in finding a place, but he moved to a hotel of a bohemian crowd where all pleasures were open to him. In time, Baldwin’s health suffered from the carnival of flesh he willingly joined. He wrote the masterful essay Everybody’s Protest Novel, a critical look at the American protest novel, and it cost him a split with Wright.

Boggs doesn’t take big liberties with this material, but the author is not above mixing gossip, name-dropping for dramatic effect, cherry-picking quotes and insights to complete a mythic Baldwin. Chronicling Baldwin’s Southern forays during the bloody civil rights campaigns where he met Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and all his brave lieutenants, he marveled at the courage that permitted these crusaders to selflessly face death from whites. He weighed the high cost of Jim Crow: “Hatred, which could destroy so much, never failed to destroy the man who hated and this was an immutable law.”

Like any literary biographer worth his salt, Boggs explained the organic ingredients in the chief Baldwin offerings, uncovering the personal events that informed the primary and secondary plotlines of the celebrated short fiction and novels, along with the character and thematic issues addressed. He explored the blending of the subplots with the primary plot in his quest to ensnare Baldwin’s readers. This enabled Baldwin to trade ideas with the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, William F. Buckley, Dick Cavett, and the elite university snobs in real time yet creatively penning Notes of a Native Son, The Fire Next Time, No Name in the Street, Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, Blues for Mister Charlie, If Beale Street Could Talk, and his final novel, Just Above My Head. Life went on as he juggled lovers, including romantic mainstays Lucien Happersberger, Engin Cezzar, and Yoran Cazac.

For a book as huge as this, it never loses its focus and passion. Boggs committed himself to not pad this biography with meaningless details or anything fake. Reading this text allowed anybody to share one of the emotional cornerstones in Baldwin, a desperation to carve out a name for himself beyond poverty, identity, and mediocrity. “Precisely that weird combination in me of helplessness & ruthlessness, of total availability & absolute elusiveness, of impenetrable stupidity & unshakeable intelligence, my charm having been that I was in nobody’s box & nobody knew my name.”

Well, Boggs has added more weight to your name and achievements already on the map, warts and all. There has been nobody like you and your type will probably come again. As my New Orleans grandma used to say, “You’re a one-type.” We, as readers from your community, salute you and your esteemed chronicler, Nicholas Boggs.