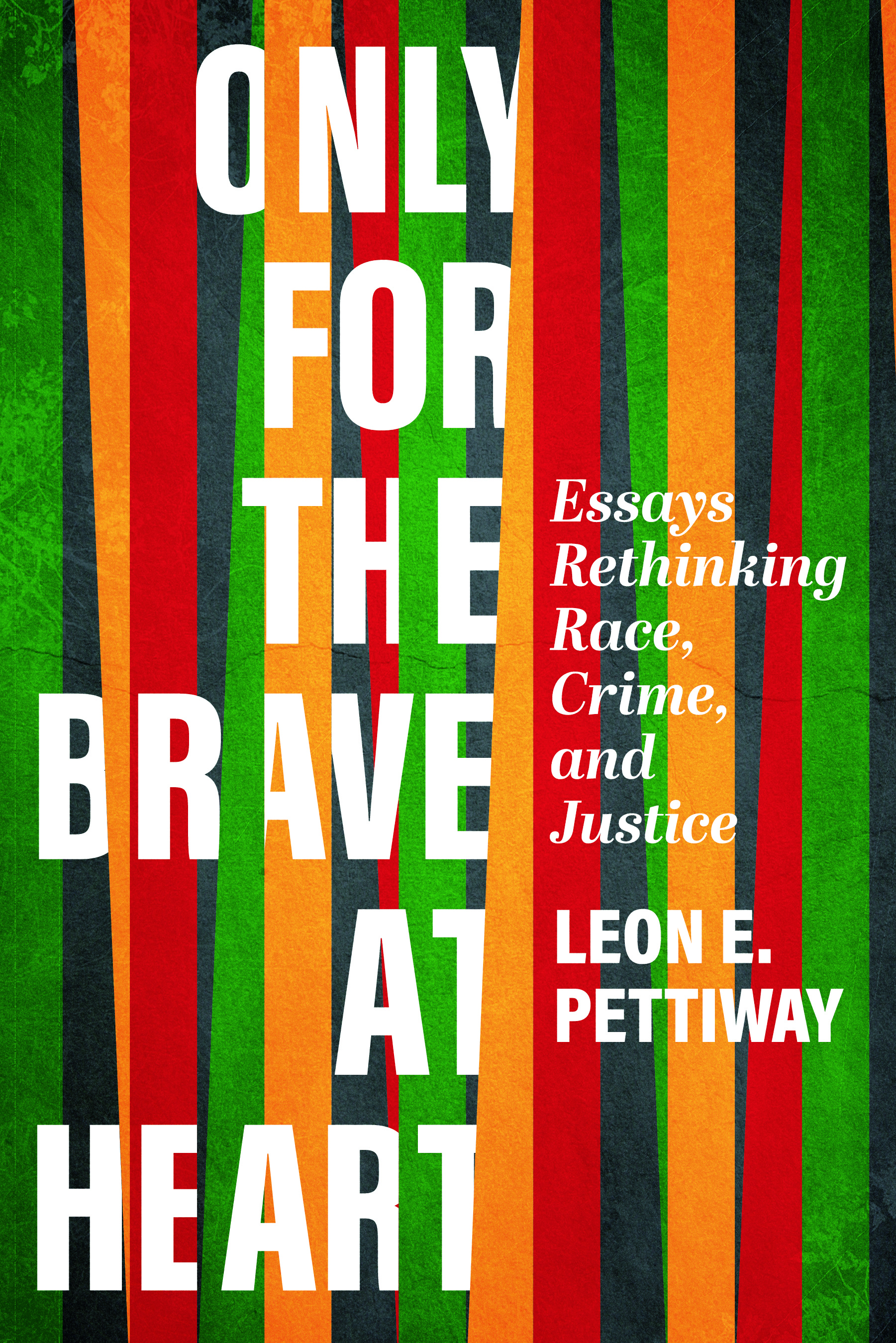

Book Review: Only for the Brave at Heart: Essays Rethinking Race, Crime, and Justice

Reviewed by:

Kirkus“A professor emeritus reimagines Western notions of race, crime, and justice in this volume of essays.

Not only has America failed to adequately say ‘I am sorry’ to the ‘descendants of Africa’s Eve,’ writes Pettiway, it has also ‘never said, “Thank you,”’ to the African American writers, artists, thinkers, and ‘ordinary people who worked with little recognition but who deserve great praise.’ This prologue, which simultaneously challenges America’s self-perception and celebrates the lives of Black men and women, sets the tone for the poignant collection of 11 essays. Divided into four parts, the book begins with an analysis of ‘The Preliminaries,’ highlighting the failures of American institutions to protect Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and others, and emphasizing that the current paradigm of crime and justice, as well as its historical foundation in white supremacy, ‘ain’t workin’.’ The volume’s second part consists of four essays that reflect on race and include an astute analysis of what Pettiway calls ‘white juju,’ which refuses to interrogate Eurocentric worldviews, and condemns, rejects, and refuses to understand those who do ‘not wish to participate in a cultural universe that satisfies, and is driven by, white values.’ Essays in the work’s third part employ an extended metaphor on Alice in Wonderland to explore issues of crime, and the book’s final section urges a reconceptualization of justice that rejects a preoccupation with retribution. Pettiway is a professor emeritus of criminal justice at Indiana University, and his research draws on his academic pedigree, boasting a 25-page bibliography and almost 500 endnotes. Yet the strength of this volume lies not in its impressive scholarly underpinnings, but rather in the author’s humane, honest, and piercing writing style. As one of the only fully ordained Buddhist monks in the Gelug tradition and as founder of a monastery in Indianapolis, Pettiway blends his astute understanding of criminal justice and sociological theory with a Dharmic spirituality and a philosophical embrace of radical definitions of love, justice, and liberation.

This formidable collection of essays offers a profound alternative vision for a more equitable future.”