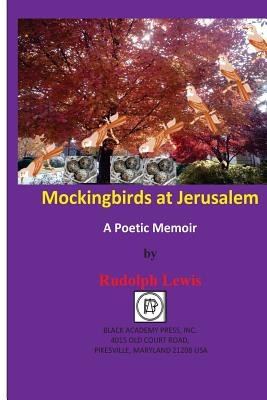

Book Review: Mockingbirds At Jerusalem: A Poetic Memoir

Parent Company: Black Academy Press, Incorporated

Reviewed by:

Miriam Decosta-Willis Rudolph Lewis

Rudolph LewisIn his lyrical Mockingbirds at Jerusalem: A Poetic Memoir, poet, editor, and former professor and librarian, Rudolph Lewis, has crafted an exquisite collection of poems of “disruptive beauty,” in which he reflects on the salient people, places, and events that have shaped his life. In these poems, initially written between 2006 and 2013 and recently revised, he employs themes, stories, motifs, forms, and techniques that underscore the depth and breadth of his memories. His poetic memoir is undergirded with a very nuanced spiritual and prophetic tone, reflective of the moral rectitude and religious values of his grandparents, his upbringing in the Jerusalem Baptist Church, the memento mori of the cemetery across the road, his four years as a librarian at St. Mary’s Seminary and University, and his philosophic and spiritual identification with Nathaniel Turner, the prophet of Southampton.

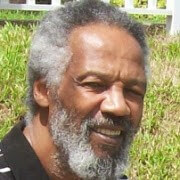

Jerusalem Baptist Church

Jerusalem Baptist ChurchMockingbirds begins with an introduction which, like much of Lewis’s prose writing, including his letters, emails, and nonfiction published in books, articles, and ChickenBones: A Journal, which he founded and edited provides details about his life that add context to his memoir. The introduction is followed by four sections of poetry: (I) “In My Father’s House,” including poems about his family and the community where he grew up; (II) “No Longer at Ease,” an introspective examination of his experiences; (III) “Reaching Beyond My Self,” a meditation on history, philosophy, and relationships; and (IV) “August Revival,” which includes poems about war, death, and destruction. From the first poem to the last, the structure of the collection is well organized and brilliantly conceived; basically, it adheres to a loose chronological order, from the poet’s youth to his adulthood, from the past to the present. But, like memory, other thoughts and themes emerge, overlap, and interrupt. For example, a poem about abandonment appears in Section I and recurs, thematically, with fewer lines but more intensity, in a poem from Section III.

Most of the poems have been skillfully revised, revealing Lewis’s craftsmanship, particularly in the use of language. The revisions, for example, in “Romance Has No Natural Death” reveal the poet’s use of more concrete, more physical, verbs and adjectives (“eaten” instead of “consumed”; “skin & bone” in lieu of “harsh”; and “mouthed” rather than “delivered”). He replaces “appear in wet dreams” with the double entendre “rise up in wet dreams,” which is much more suggestive, and he changes the meaning of the phrase “smiling behind dark veils” by substituting “snarling” for “smiling.” The long gestation period demonstrates the skill of the poet, who uses traditional poetic forms, particularly the villanelle in Part III and sonnet in Part IV, as well as more contemporary practices. Stylistically, the most salient element in Lewis’s verse is its sonorous rhythm, achieved through the use of free verse, enjambement (run on lines); and lyrical language, including similes (“clouds fade like one-night love affairs),” metaphors (“woodshed mouth”), alliteration (“soft-footed, seesaw sweetie”), and other techniques.

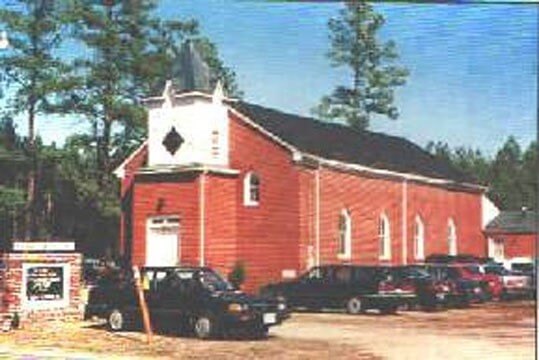

The first poem in the memoir, “My Father Still Comes to Me,” introduces the major themes of the collection: family, place, nature, and history. Deceased family members, particularly Ella, William, and Lucinda, appear throughout Mockingbirds, and the poet acknowledges that “[a]ncestor ghosts haunt my life (15).” In 1948, Rudolph Lewis was born to unwed, seventeen-year-old Lucinda Lewis but was raised in rural Virginia by his grandparentsElla “Big Mama” Lewis (1910-2009), the family singer, storyteller, and letter writer; and William “Tinka” Lewis (1905-1970), who built the family home, cinder block by cinder block. Tinka died in 1970—grayed, cut up, stretched out, and old at sixty-fivebut his grandson immortalizes him in verse as a strong man who plowed fields and constructed a tin-roofed cinderblock building. The poet sees himself in Tinka, writing, “I’m not unlike the father who raised me / silent & gloomy…(13).” With sensitivity and self-awareness, the poet intuits that he, like William Lewis, is quiet, withdrawn and pessimistic.

Rudolph Lewis’s Grandparents with son-in-law, Sam Williams (center)

Rudolph Lewis’s Grandparents with son-in-law, Sam Williams (center)In an email, Lewis elaborated upon the finances and work ethic of his grandparents: “My grandfather bought 15 acres the year of my birth, 1948. It was sold for $100 an acre, probably by loan. As a joint enterprise, my grandmother and grandfather cleared the land with mule, ax, and saw, dug a well and a hole for the outhouse (8/14/16).” In spite of his love for his grandparents, young Rudy left home at age sixteen for Baltimore, Maryland, where he underwent the intellectual and political transformation that he chronicles in his essay, “Truth’s in the Bones,” and also describes in the first poem of Mockingbirds:

I began to be man beyond the bounds of fields, barnyards, pigs & chickens. Books

& picket signs, college & blackness borne brave new worlds. (13)

These two images—fields and books illustrate succinctly the two separate spaces that the poet inhabits: the rural landscape of his childhood and the urban cityscape of his adulthood. Like the mockingbirds that appear on every other page symbols of intelligence and protection the narrator is in flight, moving from and returning to his rural home, as he observes others from a safe distance

He left home as a young man and returned to Jerusalem, to stay for several years, at middle age, but his family was very different from that of his remembered childhood. William had died years ago; Ella now had dementia and was cared for by her daughter Ann. He recalls, wistfully, that, in her youth, “Mama pulled buckets, mud & clay heavy, for / water to drink, washed away fields & harvest (13),” With two lines and a single image (drawing water), the poet underscores the hard life of a country woman who works from sunup to sundown. In another poem, “Tears of the Devil’s Wife,” this country woman, like Fannie Hamer, is emblematic of fierce, shotgun-strong Black women who sought freedom in “lynched-heated southern woods” (48). As a storyteller and letter writer, Ella is also an archetype of the ancient griot, the one who, through her gift of storytelling, holds family and community together. In the mystical poem, “Reparations Along the Nottoway,” with its allusions to native gods, arrowheads, and Snake people, Lewis intercalates one of Ella’s stories: “When Mama was twelve…she rode Duke bareback to the doctor’s office / up in Jarratt Town (68).” He discovers, however, when he returns home, that Ella is now half-blind and delusional—not the strong, creative woman whom he remembers.

Family Hoome

Family Hoome Lucinda, Rudolph Lewis’s Mother

Lucinda, Rudolph Lewis’s MotherThe other major woman in his memoir is Lucinda (1931-2008), the poet’s biological mother, the subject of a short nonfiction piece and two poems“My Mother Don’t Like Country” and “Home Is Where Relief Is.” The poems deal with the troubled relationship of mother and son. Lucinda leaves her rural home for “a red-brick row house in Yale Heights (62),” while her son remembers “standing on the roof (24)” when she left. The image of the Abandoned Boy on the rooftop is repeated in a second poem: “I was on the roof of the storehouse when my mother left to return to Baltimore with her better son (62).” The mother and son, significantly, are diametrically opposed; one is moving away and the other is standing still. The poem continues: “She chose to / leave me in her father’s world to maid & seamstress & birth / five more (24).” The use of the nouns “maid” and “seamstress” as infinitives is a powerful and creative use of language for dramatic effect. Meanwhile, the son stands on the roof, feeling abandoned and sensing his mother’s preference for “her better son.” Looking back, the man remembers the boy: “I am rooted up, torn by a childhood past. Abandoned. (62)” Abandonment and exile are two significant motifs in Mockingbirds. The abandoned child on the roof is passive, having no control over his life, but the teenager on a Trailway Bus heading up highway 301 into exile is the active agent of his own destiny. Both the passive and active states, however, lead to displacement and existential loneliness, for the poet writes: “I’m a Jim Boy in / a self-exile scribbling to make sense of absurdities…(58).” This image—Jim Boy, a self-exile—underscores the solitude and loneliness of the narrator who retreats to the woodshed, where his only companion is Bobo Cat, a beloved animal who appears in four poems, including “Bobo at Jerusalem.”

Bobo endured long dark night alone in outhouse. My

buddy stretches out & naps. I fear my folk tradition:

they don’t like cats in house. (16)

Also indicative of this feeling of aloneness and separation from others is the second paragraph of the introduction, in which Lewis switches suddenly from the first person (I) to the third (He): “This distorted place could and will never be one of permanence for a smart black boy. He will always seek to fulfil his self in other spaces. Jerusalem generates exiles.” In the sentence that follows, he returns to the first person, with which he began his introduction. This peculiar shift in point of view subconsciously prepares the reader for the tone of Lewis’s poetry, which is somber, brooding, and distant.

Distant, like his relationship with his biological mother, Lucinda, who died unexpectedly, in May 2008, after celebrating Mother’s Day with her four daughters and “better son,” with whom she was living. Apparently, her first son was not invited and did not attend the Mother’s Day celebration, nor, apparently, the funeral service for his mother. Indicative of the complexity of his feelings for the woman who birthed him is the title of his prose obituary for Lucinda, “Rattlers and Other Acts of Love.” Perhaps, the oldest son was problematic for his mother; he certainly was not like her. By all accounts, she was an unlettered, unskilled, country woman; he, on the other hand, was a scholarly, urbane, and philosophic man who expressed himself through writing. After his mother’s death, he wrote:

My eyes are watered. No tears have yet fallen. So many thoughts

pass through my mind. I have never lost a mother before. Two fathers

have been gone for sometime. We now break new earth.

With the breaking of “new earth,” it is as if the adult son realizes that one phase of his life is over-marked by the deaths of his biological parentsand another is beginning.

Rudolph Lewis’s Grandmother

Rudolph Lewis’s GrandmotherSignificantly, the portraits of Lucinda, Ella, and Tinka are sketched within the spaces they inhabit: Lucinda is viewed in an urban space of “hotel & factory,” while Ella and Tinka are pictured in a “country of mules [and] outhouse.” In fact, the sense of place is a major strength of this collection, as the poet describes cities in which he lived—Baltimore, New Orleans, and Bulavu in the Democratic Republic of the Congoby allusions to people and landmarks: gunshots and Pennsylvania Avenue; Marie Laveau and Mardi Gras; and tribal men and Lake Kivu. He evokes the rural flavor of his home in southeastern Virginia through lush and sensual descriptions of (1) natureforest nights, green pines, and soaked fields; (2) landmarksDismal Swamp, Nottoway River, and Sansi Swamp; and (3) people—Malvinia, Sue Gal, and Miss Lula Bell. Jerusalem is a key word in the title of this poemario, as well as a symbol that resonates throughout the book. Although Lewis grew up in his ancestral homeland of Jarratt (to which he alludes only once), his spiritual center is Jerusalem, Virginia, because of its religious and historical significance. In the New Testament, Jerusalem is the ancient town in the Holy Land where the Christian saviour was crucified. Historically, as he writes in Mockingbirds, “Former slaves built Jerusalem plank by / hewed plank…(79).” Jarratt and Jerusalem (now Courtland) are both located in Sussex County, about four miles apart. His home is in Jarratt Town, a community founded by freedmen in 1870, and the family worships at Jerusalem Baptist Church, which was built by slaves.

The poet makes over twenty allusions to Jerusalem, the seat of Southhampton County and the Virginia town in which Nathaniel Turner was hanged in 1831. History runs, like a leit motif, through every page of Mockingbirds. In August 1931, Nathaniel Turner (1800-1831), led a rebellion of enslaved and free men, who murdered 55 to 65 Whites. Eventually, he and his men were captured, tried, and sentenced to death. Called “The Prophet,” Nat Turner was a brilliant and deeply religious leader, who had visions and spiritual revelations. He also stimulated the creative writing of Rudolph Lewis, who references the prophetic rebel in three poems: “August Revival,” when Jerusalem townsfolk commemorate Turner; “Loving That Other Man”; and “Sonnet for 22 August 1831,” the date of the rebellion. Significantly, Lewis was born in August and named the website of his journal for the resistance hero: www.nathanielturner.com.

Although the word “Jerusalem” has religious connotations and Lewis was baptised in Jerusalem Baptist Church, his poetry is not religious. He writes: “2nd Sunday services—nightly writhing to Friday / testifying & preaching—pointless vigils (74).” The poet seems proud of the historical significance of the church to his family and community, but he calls the rituals of the Black church “pointless” and uses the pejorative word “writhing” to describe one of its rites. In response to a question about St. Mary’s Seminary and University, he seemed to confirm this interpretation, writing: “A Ghanaian Ph.D. thought I was irreligious, mocking God. He wasn’t lying. (12/4/16).” His poetry is, however, very spiritual, as these lines from various poems seem to indicate:

I gather ancient spiritual energy (49)

Resistive we pray for rescue (50)

the woodshed that stores prayers and poetic feelings (60).

I learned how to

pray (65).

I…listen for God’s voice to speak as / my ancestor (71).

Like an Old Testament prophet, Lewis examines the historical past and describes the present, but it is his wise and weighty tone, with its sturm und drang, that makes Mockingbirds at Jerusalem a philosophic and spiritual tour de force.

Lewis, Rudolph. “Introduction.” Mockingbirds at Jerusalem: A Poetic Memoir.

“Rattlers and Other Acts of Love: An Obit Assembled by Rudolph Lewis,” www.nathanielturner.com

“Rudy’s Place.” www.nathanielturner.com.

“Truth’s in the Bones.” Passing It On: Moving Stories of Activists–1960 to 2000. Bev Jenai-Myers, ed. Bloomington, IN: Archway Publishing.

Lewis, Rudolph to Miriam DeCosta-Willis. 14 August 2016, 4 December 2016.