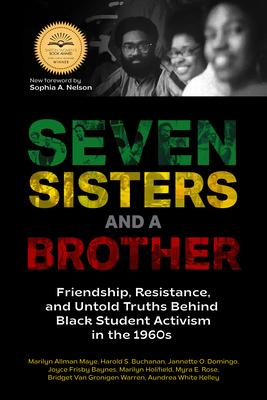

Book Review: Seven Sisters And A Brother (paperback): Friendship, Resistance, and Untold Truths Behind Black Student Activism in the 1960s

by Marilyn Allman Maye, Harold S. Buchanan, Jannette O. Domingo, Joyce Frisby Baynes, Marilyn Holifield, Myra E. Rose, Bridget Van Gronigen Warren, and Aundrea White Kelley

List Price: $19.95Books & Books (Dec 02, 2021)

Nonfiction, Paperback, 356 pages

More Info ▶

Book Reviewed by Denolyn Carroll

History has recorded many instances of struggles for varied rights by a people haunted by the legacies of slavery. Yet, too often some such occurrences, though no less noteworthy, never make it into the annals of history; they exist instead as footnotes at best. With Seven Sisters and a Brother: Friendship, Resistance, and Untold Truths Behind Black Student Activism in the 1960s authors Marilyn Allman Maye, Harold S. Buchanan, Jannette O. Domingo, Joyce Frisby Baynes, Marilyn Holifield, Myra E. Rose, Bridget Van Gronigen Warren, and Aundrea White Kelly have helped ensure that their story secures a solid place in the ongoing narrative. A “choral memoir,” Seven Sisters and a Brother is a decidedly informative documentation of the efforts of eight students (seven young women and one young man) in the late 1960s to have Black students get the opportunity, resources, and support needed to acquire a balanced education at the elite Swarthmore College.

A small, private, picturesque, coed liberal arts institution in the suburbs of Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, Swarthmore College was founded in 1864 by prominent Quakers. Despite the fact that equality is a core Quaker value and that Quakers have a long history of fighting against slavery, the first Black student was not admitted into Swarthmore until 1943. In 1964, it was external funding from such organizations as the Rockefeller Foundation that helped to steadily increase the number of Black students enrolling in Swarthmore and other such colleges. The eight students, who met as undergraduates between 1965 and 1966, “were surprised to discover that [theirs] were the first classes with more than a handful of Black students.” They were “shocked to later find out that the absence of blacks was intentional.”

As they note in the chapter of the book titled “The Swarthmore Experiment,”

Our group of seven sisters and a brother did not go to Swarthmore to change the College. Our aim was simply to get a good education and enjoy college life, but it didn’t take long for us to discover inconsistencies in the Swarthmore story. Elite colleges pride themselves on their rich heritage and time-honored traditions…Swarthmore’s de facto policy to deny admission to Black students was also a tradition and part of its heritage, but one that was wrong and contrary to the Colleges’ espoused values.

By the time the eight met up at Swarthmore, international and domestic conflicts around civil rights were rife, and college students were increasingly committing to the “struggle.” In 1968, the group, which was already active on campus, formally established the Swarthmore Afro-American Students Society (SASS). “SASS,” they clarified, “was not founded specifically to address the College’s shortcomings, but when Black students came together in this organization, it was inevitable that the persistent inconsistencies in the College’s policies would be brought to light.” The subsequent outlining of grievances and the confrontations between the group and the College yielded no changes from the school’s administration.

In the fall of 1969, frustrated by the college’s lack of response to their demands, the Seven Sisters, plus one Brother came up with the idea of engaging in a peaceful sit-in in the College Admissions Office. The number of students who joined in the actual “Takeover” grew as the hours and days wore on, as did backing from supporters on- and off-campus. Soon the administration characterized the protest as the “Crisis,” providing grist for the rumor mills and conspiracy theorists.

SASS clarified their goals as follows:

Through letters to the administration, public statements, and articles we submitted to the College paper, the entire campus understood that we wanted the College to enroll more Black students, hire Black faculty and administrators, launch a Black Studies Program, remove the offending Dean of Admissions (if he refused to change), and institutionalize supports for Black students such as a Black cultural center and a minority dean.

On Day 8, news that the College’s president had died from a heart attack brought an abrupt end to the sit-in, at a point when the faculty was soon to take a decisive vote on the students’ demands. Ultimately, the administrators granted the requests, and the students involved in the protest were allowed to start the spring semester “without penalty, as long as [they] agreed to act in good faith.’”

As the group notes,

Little did we know that forty years later, the College administration would call our action the single most consequential event in its 150-year history. What they called the”Crisis” was the cataclysmic event that forced college administrators to wake up and respond to our demands for respect. Respect for Black people. Respect for Black history. Respect for Black culture. Black students refused to be invisible.

Indeed, the individual stories of the eight students who decided to put their future on the line in order to make a push for visibility and fair treatment provide the humanity and the glue for this memoir. The students’ varied backgrounds and perspectives—hailing as they do from Florida, Virginia, New York, Massachusetts, and the Caribbean—give readers a glimpse into the multifaceted nature of Black lives and culture, while their struggle during the turbulent 1960s holds a mirror to our current crises.

Seven Sisters and a Brother is well written, reflective, relevant, and engrossing. It is not only yet another reminder of the toxic racism at the core of this nation but also a resounding call for school administrators to right the blatant wrongs that still persist in our educational system. The changes effected at Swarthmore and beyond as a result of a body of students taking a stand is remarkable in itself. It is also interesting and commendable that the eight students could see how each chapter of their lives prepared them in some ways for the testing years at Swarthmore College, and how those years at the school in turn helped make them successful and influential individuals ready and able to pull up others.

It wasn’t until 2009 when the group was invited to the fortieth anniversary of SASS to share their stories about the founding of the organization that they were able to give a collective full and truthful account of what led up to those fateful eight days, and their aftermath. Their telling was met with much acclaim, and they set out to officially “capture their memories.” The result: Seven Sisters and a Brother, which was first published in hardcover in 2019, then followed by a paperback reintroduction in 2021. The story has been told, and its recording is required reading.