Book Excerpt – The Victory of Greenwood

The Victory of Greenwood

by Carlos Moreno

List Price: $34.00Jenkin Lloyd Jones Press (Jun 02, 2021)

Nonfiction, Hardcover, 360 pages

More Info ▶

Introduction and Chapter 9 – B. C. Franklin

“Time is an enormous, long river, and I’m standing in it, just as you’re standing in it. My elders are the tributaries, and everything they thought and every struggle they went through and everything they gave their lives to, and every song they created, and every poem that they laid down flows down to me—and if I take the time to ask, and if I take the time to see, and if I take the time to reach out, I can build that bridge between my world and theirs. I can reach down into that river and take out what I need to get through this world.”

—Utah Philips

This book is dedicated to James O. Goodwin, E. L. Goodwin, Jr., Louis Gray, Oklahoma State Representative Don Ross, J. Kavin Ross, Changa Higgins, Sean LeClair, Chief Egunwale Amusan, Gail Crum, Phillip Winfrey, and the rest of the team at the Oklahoma Eagle, 2002. Working on the special issue covering the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre was an unforgettable experience for which I will be forever grateful.

INTRODUCTION

In 2002, I was called into Louis Gray’s office at the Oklahoma Eagle. Louis (Wah Sha Nompe) was the newspaper’s managing editor, an Osage member of the Deer Clan and tall-dancer, and the epitome of an elder journalist—complete with copious cigarettes, coffee, and fierce opinions. His brother, Jim Gray, was also in the newspaper business, having founded the Native American Times in 1994. I’d previously done some freelance graphic design work for the Eagle, an occasional website update or banner ad. This time, Louis was asking me if I’d be willing to work on a much bigger project—a special issue of the Eagle that would tell the history of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. The state of Oklahoma released “Report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921” the previous year, but it had gotten very little press, wasn’t widely circulated, and was a dense, academic, 200 pages long. The Eagle’s goal was to publish something more engaging and accessible for its readers.

Just as crucial as getting the story out was the fact that the Eagle’s publisher Jim Goodwin, a Notre Dame educated attorney, along with other Tulsa attorneys Leslie Mansfield, Jim Lloyd, and Sharon Cole Jones, had assembled a national 14-person legal team which included Adjoa A. Aiyetoro, Johnnie Cochran, and Charles J. Ogletree, Jr. to prepare a lawsuit against the City of Tulsa, the Tulsa Police Department, and the State of Oklahoma. The suit demanded reparations be made to the Massacre’s survivors and their descendants, as recommended in Oklahoma’s 2001 report. The special issue needed to be done in time to publicize the filing of the lawsuit in the U. S. District Court in Tulsa and raise public support for Introduction the cause. The paper’s in-house graphic designer, Sean LeClair, also Native American, was too busy working on getting the weekly to press on time, and Louis asked if I was interested in helping out. I immediately said yes.

I had no idea how to design anything in print. I learned how to create websites in 1996 while still at San Jose State University, part of the campus’ technology help desk staff when I wasn’t in classes. I dropped out of school and moved to Tulsa in October 1998 to be with my then girlfriend, now wife (it worked out!), and after leaving a website design company on Brady Avenue (today Reconciliation Way), and then an internet consulting company, was looking for what to do next. There weren’t a ton of opportunities open in Tulsa for a 24-year-old Latino web designer. I’d wanted to start my own design company, but banks and investors weren’t interested. The Tulsa Chamber didn’t much care. And I wasn’t having luck getting any clients. Greenwood—what was left of it—was the only place where business owners and nonprofit leaders took some time to listen to what I had to say. All my first web design clients were in Greenwood: I built web pages for the Greenwood Cultural Center, the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce, the Mabel Little House, A Pocket Full Of Hope, musician Lester Shaw, the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame, and a few businesses in the neighborhood.

I left the meeting with Louis and drove straight to the bookstore to find a book on how to use Adobe PageMaker. I asked my friend and fellow graphic designer, Saif Khan, to get me a bootleg copy of the software so that I could start learning that weekend. I spent the following weeks learning about the history of Greenwood from Jim Goodwin, his older brother, journalist and photographer E. L. Goodwin, Jr., State Representative Don Ross (who had co-sponsored legislation to establish the Tulsa Race Riot Commission in 1997), and Rep. Ross’ son Kavin. Several other members of the Eagle staff and people in the community contributed to the creation of the special issue. It was printed in February 2003, at the same time the lawsuit was filed. The case was dismissed by the federal court in Tulsa and the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals in 2003, and was denied a hearing by the U. S. Supreme Court in 2005.

Life moved on. Saif and I started the web design company I’d wished for, Toydrum Inc., with another business partner, Rodney Giles. We started in a shared office with another company I’d helped launch, a bilingual newspaper La Semana Del Sur. Jennifer and I were married in 2004, and our daughter was born in 2007. After a few years and a few great clients, Toydrum split up. Saif and I worked on a couple of last projects together before finally deciding that we both needed to start looking for regular jobs. During this time, we met Bishop Carlton Pearson. He and his staff, Nicole Ogundare, Cassandra Austin, David Smith, and Ben Shell, were working to support Bishop Carlton in publishing his first book, The Gospel of Inclusion.

Carlton had become as infamous for preaching ideas heretical to mainstream Christianity (such as the absence of hell and LGBTQ+ inclusion) as he had been famous for being the high-spirited prodigy of megachurch televangelist and godfather of the charismatic movement, Oral Roberts. As we worked to build the website for his book, we also had long conversations about his evolved perspective and changing faith, about civil rights, history, community, and about dealing with pain and loss. Carlton helped me process the complex emotions I had about losing my uncle Richard in 1994 to AIDS, and helped me forgive my family for not accepting Richard for everything he was. Just as I’ll never forget holding the printed edition of “1921 Race Riot. What Was…What Is” in 2003, I’ll never forget sitting in Ben Shell’s house watching Carlton’s interview on NBC in 2006, while the website visits and book sales through the website climbed higher and higher.

My life and career moved on, but the story of Greenwood stuck with me. Through the years, I’ve read books, reports, academic and newspaper articles, historical documents, court cases, studied maps, plats, and land deeds. I talked about Greenwood with Tulsa’s experts on the history of the neighborhood, folks like Larry Silvey, LeeRoy Chapman, Ann Patton, Michael Bates, and more recently Victor Luckerson, Timantha Norman, Jessica Shelton, Dr. Alicia Odewale, Quraysh Ali Lansana, and Reverend Robert Turner. Every time I’ve read, spoken, written, or listened to a story about Greenwood, I’ve uncovered more. As I looked at my bookshelf, I realized that most everything written about Greenwood is about the 36 hours of the Massacre, not about the 15 years before or 100 years after.

About the time our daughter was four years old, Jennifer and I felt that we needed to find a church home. We’d attended just about every Catholic church in Tulsa before we got married, and for a time, were somewhat happy at Church of the Resurrection until Father Michael Knipe moved. We knew a few friends at All Souls Unitarian Church and were intrigued that senior pastor Marlin Lavanhar and Bishop Carlton Pearson had chosen to merge their congregations. We decided we’d attend All Souls’ Easter service and see if it might be a fit. I think it’s safe to say we both instantly felt that this was the church for us. I was overjoyed to connect again with Carlton and those who had followed him on his new journey with the Unitarian Church. I also knew that all was not sunshine and roses, and even inside the church walls, there was a lot of racial healing work yet to begin. I felt up to the challenge.

One of the first things I learned about All Souls is that it was founded in March 1921 by Richard Lloyd-Jones, the owner and editor of the Tulsa Tribune during the time of the 1921 Massacre. In the months and days leading up to May 31, Jones wrote a series of horrifically racist editorials attacking Greenwood and its leaders. Jones went so far as to hire Reverend Harold G. Cooke of Centenary Southern Methodist Church, and a private detective to investigate Greenwood’s “crimes.” What they found was truly shocking—the same amount of gambling, prostitution, and alcohol that was in full swing two blocks south of Archer Avenue was going on in Greenwood (the next time you’re enjoying margaritas at El Guapo, ask your server what the building used to be). “We found whites and Negroes singing and dancing together,” one member of Reverend Cooke’s party testified, “Young, white girls were dancing while Negroes played the piano.” This is what incensed Reverend Cooke, Lloyd-Jones, and Tulsa’s well-to-do the most. How dare this place allow young Black and white men and women to enjoy themselves together?

The morning after Dick Rowland accidentally stepped on Sarah Page’s foot in an elevator in the Drexel building, he was arrested by a Black and by a white officer, who escorted him to the Tulsa police station downtown. Lloyd-Jones wrote a short editorial with the headline, “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl In an Elevator.” At 3:00 that afternoon, Commissioner J. M. Adkinson received a phone call threatening Rowland’s life. Adkinson and Police Chief John Gustafson decided that Rowland would be safer at the jail on the top floor of the County Courthouse and moved him there. That evening, a white mob gathered to do precisely what Jones had instructed in his headline. The problem was that everything in Jones’ article was wrong. Page had not been attacked. She never pressed charges. She and Rowland were friends, possibly more. Fed a steady diet of lies, incited by racist rhetoric, and given support by some members of the police and national guard, a white mob attacked.

We have a citywide narrative that begins with Page and Rowland in an elevator and ends with Greenwood—40 blocks of businesses and homes—destroyed, with nothing happening after that for 100 years. We’ve never sifted through the ashes to find out what happened before or after the Massacre. That’s never sat right with me. That isn’t the Greenwood I learned about from the people I worked with in the neighborhood in the early 2000s.

This isn’t a book about the Massacre. This is a book that tells the story of Greenwood the way it was told to me. This book, I pray, is a conversation. Let’s take a look at the evidence we now have in front of us and establish some facts, and dispel some myths, together. The attack on Greenwood was planned. Greenwood was going to get burned down whether Rowland had gone to the Drexel building or not. Planes were used to bomb Greenwood with balls soaked in turpentine. Greenwood’s residents rebuilt their neighborhood better than before, despite Tulsa’s government and business leaders’ best efforts to prevent them from doing so. Greenwood thrived for more than 45 years after 1921, and played a significant role in the movement for civil rights in Oklahoma and nationwide beginning in the late 1950s. The music world, the world of aviation, the military, Black journalism, the Pentecostal and African Methodist Episcopal churches in the U. S., the petroleum industry, the internet…and so much more, would not be what it is today without Greenwood.

Let’s begin a new conversation about Greenwood. Not one that places it in the past or diminishes it to an object of pity. Let’s honor its past, its sacrifices, and let’s begin to do right by the more than 300 people who died, as well as the thousands held in detention camps and left homeless. Let’s remember that the destruction that failed in 1921 succeeded in 1971 and 1991 and continues today. Not out of guilt or shame, but out of respect and love. Let’s—for once—listen to Greenwood and discover the positive impact it has had on the nation and the world for more than 100 years. Let’s ask what we can learn from Greenwood, not what empty symbolic gesture we can make that eases our guilt but does nothing to help this place and its people. I pray that you’ll see Greenwood through Greenwood’s eyes; that you will connect to Greenwood with your heart, as I did.

9 — B. C. Franklin

B. C. Franklin’s autobiography, “My Life and an Era,” takes its readers back in time to a period of Oklahoma’s history when Black families enjoyed an abundance of prosperity, peace and freedom. His parents were Choctaw and Chickasaw, and were both highly respected in Indian Territory. Growing up, B. C. learned as much from working on his family’s farm as he did in the schoolhouse where his mother taught. He benefited not only from the great respect his family had earned in Indian Territory, but also from the incredible growth of all-Black towns in the Territory—more than 50 between 1865 and 1920. Black excellence was the cornerstone of Franklin’s life, which he tirelessly upheld throughout his career. Like many of his contemporaries, he balanced numerous professions. He was an attorney, a skilled rancher, a newspaper publisher, a postmaster, and a talented writer. His autobiography serves as the most complete picture of the accomplishments of the Black community in pre-statehood Oklahoma and the struggle to preserve what they had gained during the rise of segregation and racial hatred.

Black Prosperity in Indian Territory

David Franklin was born David Birney in 1820, in Tennessee, near the town of Gallatin. At the time of the Civil War, David escaped from his owners (Chickasaw tribal members who had moved from Tennessee to Indian Territory in 1830) and joined the Union army, using the name David Franklin.

David’s brother, Alexander, lived an equal amount of time during his early life in Tennessee and Virginia. Alexander was acquainted with some of the families related to President Thomas Jefferson’s former slaves, who were all sold or freed between 1827 and 1830, several years after Jefferson’s death. The Franklin family believed Jefferson to be an abolitionist. In his 1785 “Notes on the State of Virginia,” Jefferson wrote that slavery was demoralizing to both white and Black society. Nonetheless, Jefferson favored the segregation of the two races and believed Black people to be inferior. The Franklin family was also staunchly political and fought for Black freedom. Alexander served in the Second Seminole War (1835 - 1842) and convinced his brother to enlist with the Union army.

Under the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek in 1830, the Choctaw Tribe was removed from their native land in Mississippi and relocated to Indian Territory. Millie Colbert Franklin, a one-fourth Choctaw Indian, was raised in the tribe’s customs and spoke Choctaw fluently. David and Millie were married in 1856, near Biloxi, Mississippi, and moved to Pauls Valley in Garvin County, Indian Territory. They later moved further east near Homer, Pontotoc County, where David settled on a 300-acre spread in what was then communal land in the Chickasaw Nation. When David enlisted to fight in the Civil War in 1864, his brother, Alexander—along with two other siblings, Bailey and Matilda—moved to Homer to help Millie tend the family farm.

Buck Colbert Franklin was born on May 6, 1879, the seventh of David and Millie’s 10 children. He was named Buck in honor of his grandfather, who had been a slave and purchased his freedom. His siblings were Andrew, Walter, Dolores, Thomas, Hattie, Matthew, David Jr., Fisher, and Lydia Franklin. By this time, B. C.’s father had gained national notoriety as a rancher trading cattle, horses and hogs throughout Indian Territory, as well as in Kansas, Texas, and New Mexico.

1886 proved to be a victorious and tragic year for Millie Franklin. She had retired from teaching at the end of the school year. That summer, she was visited by her brother Andrew, who was traveling with Reverend J. S. Pinkard. The two were working to establish Colored Methodist Episcopal (C. M. E.) churches throughout the Territory. C. M. E. and A. M. E. churches were gaining popularity among Black Christians. They saw the relatively new denomination as a desirable alternative to the mostly white-influenced Baptist churches. While Millie was raised in the C. M. E. church, her husband was staunchly Baptist. Nevertheless, he felt that he could not betray his wife’s family’s wishes, convinced the pastor of Salem Baptist Church in Pauls Valley to host Pinkard and his followers, and helped establish the new church.

During the winter of that same year, Millie traveled to the Choctaw Nation’s capitol in Tuskahoma to prove her Choctaw citizenship. While the Dawes Act of 1887, (which would change the arrangement of tribal communal land to a system of individual land allotments for families) would not be extended to any of the Five Civilized Tribes until the passage of the Curtis Act of 1898, the family knew that the political winds were already changing and that the family might lose what they had built. She successfully put her affairs in order, but became ill on her trip back home and never recovered. Millie passed on December 25, 1886.

The Franklin family ranch continued to prosper until David Franklin died of “dropsy” (edema) in 1900. The elder Franklin was remembered not just as a great rancher, but a great man of his community, using his wealth to improve the town’s school, churches, and building prosperity for his business colleagues.

Education and Family

By the age of 11, B. C. could skillfully ride a horse, hunt deer, cook for the family, and perform most of the chores on the ranch. His father had brought him along on a business trip to Guthrie in 1890, where the two had the opportunity to meet Governor Washington Steele. This would prove to be a foundational experience for young B. C. Franklin. He saw Black attorneys, judges and prominent businessmen participate in the shaping of the Territory. He aspired to make a difference in his community, like his father.

Before his college days, he enjoyed a great deal of achievement as an athlete and rancher, winning several competitions, similar to rodeo contests. He knew the famous federal lawman Bass Reeves, as well as several other Black jailers and lawmen. He was also a successful student, attending the Dawes Academy boarding school near Springer in Carter County. After graduating from Dawes Academy, Franklin was accepted into Roger Williams University in Nashville, Tennessee.

Franklin greatly enjoyed his experience at Dawes Academy, finding support from professors such as John Hope, who taught science. Another of Franklin’s professors, William Henry Harrison (who Franklin described as one of his best friends), brought the case McCabe V. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Company, 235 U. S. 151, to the Supreme Court, challenging Oklahoma’s Senate Bill One. The state legislation asserted that trains passing through Oklahoma were to “provide separate coaches or compartments for the accommodation of the white and negro races.” Though the court upheld the state law (which would not be overturned until 1965), Franklin saw Harrison’s fight for racial justice as an example of the heights his career could reach.

He also admired Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Institute, where George Washington Carver made his greatest agricultural discoveries. He befriended the Baptist minister C. T. Walker, whom J. D. Rockefeller, Jr. considered a good friend. He understood that he needed to leave his home and study at a more prestigious school. Shortly after his father passed, Franklin followed his mentor, John Hope, to Atlanta Baptist College, which today is known as Morehouse College. There, he would meet Mollie Lee Parker. The couple married on April 1, 1903. The couple struggled to maintain their studies as well as keep up with the affairs of managing a large homestead. After losing nearly all of the wealth from his father’s farm due to debts and an illness that killed off all of the ranch’s hogs, the young couple both took jobs as teachers in Springer and later moved to Ardmore.

From Farmer to Lawyer

While tending to the new smaller homestead and his job as a teacher, Franklin took a correspondence course to earn his legal degree. He passed the bar exam and was admitted to the Supreme Court of Oklahoma on August 8, 1908. By this time, Oklahoma had become a state, and racial and political tensions increased. Fraud and corruption in order to steal land from Black and Freedman farmers became rampant. Lynchings of Black citizens in Indian Territory were relatively rare compared to the rest of the South, but after statehood, the danger of Black men being lynched grew significantly.

Franklin decided to focus on practicing law within African American communities. The family moved to the all-black town of Rentiesville, Oklahoma in 1912. There, he and Mollie had 4 children: Mozella Denslow, Buck Colbert Jr., Anne Harriet and John Hope (named after Franklin’s long-time mentor). In Rentiesville, Franklin established his law practice, a newspaper named the Rentiesville News and took over the job of postmaster. In his autobiography, he describes how balancing all these jobs was too much for him. He could not do any of his work well and was getting by with only three hours of sleep a night.

A significant amount of Franklin’s legal career was focused on defending the land and mineral rights of Natives and Freedmen. They were often the victims of falsified records, conspiracies between oil companies and judges to devalue and then buy land allotments, and fraud over rightful heirs to land (which journalist A. J. Smitherman referred to as the “Guardianship Racket”). This may have been because his own family had their mineral rights stolen from them. Though his mother was one-fourth Choctaw, she passed away before the passage of the Final Rolls of Citizens and Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, also known as the Dawes Rolls. After his father passed, even though he and his siblings were listed on the Dawes Rolls and were given land allotments in Garvin County, southwest of Pauls Valley, a forged mortgage was placed on the land allotment of his brother, Tom. The family fought the forgery in court, but ultimately lost this land, on which there was a substantial oil reserve. Tom should have amassed millions to pass down to his family. Instead, he died penniless.

Nonetheless, Franklin was persistent in furthering his legal career and heard of an even greater opportunity in the booming neighborhood of Greenwood in Tulsa. His plan was to move to Tulsa in February 1921. When he’d created enough of a nest egg, his wife and children would move from Rentiesville and join him in Tulsa soon after.

Lawsuit Against the City of Tulsa

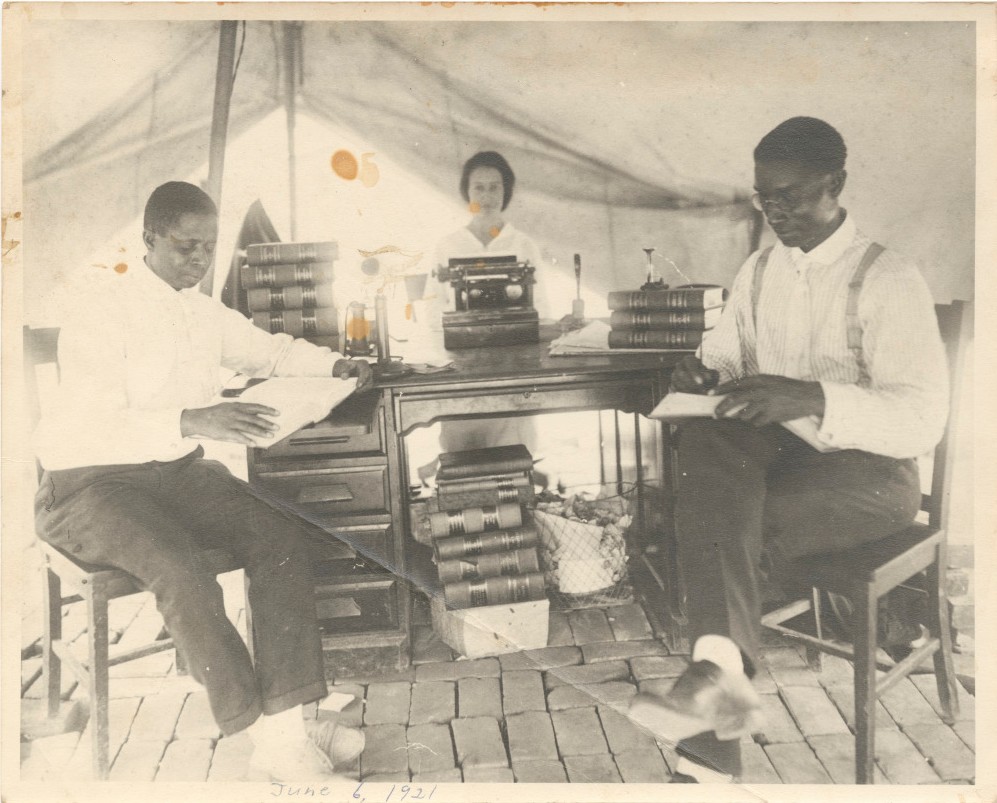

The photograph is one of the most well-known in Greenwood’s history: In a tent established as a legal office, attorney I. H. Spears, secretary Effie Thompson and B. C. Franklin, equipped with only a desk, a stack of legal books and a typewriter, set about the task of seeking justice for the victims of the Massacre. From this tent, Spears, Franklin and P. A. Chappelle would build a legal case against Mayor T. D. Evans and the City of Tulsa.

Franklin was new to Tulsa. He wasn’t aware of the racial tensions that had been building, which were made even more provocative in the columns of the Tulsa Star and the Tulsa Tribune. What Franklin did recognize was white greed for Black-owned land. On June 7, 1921, one week following the destruction of Greenwood, the City Commission voted unanimously to extend the jurisdiction of Tulsa’s fire codes, allowing for the city to “[govern] the construction, erection, alteration, repair, remodeling, re-building, moving, demolition, securing the inspection of building a structure and appurtenances thereto within and for the additional extension of the fire limits.” The following week, Mayor T. D. Evans forced the resignation of the Public Welfare Board (assembled by the Chamber of Commerce to collect a fund to help Greenwood rebuild) and presented a plan to create a new train depot and commercial development in the burned Greenwood business district. The plan was led by Tate Brady, Stephen Riley Lewis, and Frank Long. Mayor Evans and Commissioner Herman F. Newblock then created a new “Reconstruction Committee” to implement this plan and move Black residents and businesses further north out of the downtown area.

In filing the Tulsa County Case No. 15730, Joe Lockard vs.T. D. Evans, et al., Franklin’s courageous legal team brought the City of Tulsa, the Mayor, the City Commission, the Chief of Police and the building inspector for the city to trial. The case centered around the city’s right to prohibit Greenwood’s existing property owners from rebuilding on the land they owned. Franklin asserted that the new fire ordinance did not contain any language regarding the penalty for violating the new fire codes and that the ordinances were a violation of Tulsans’ property rights. As the case dragged on into the summer months, Greenwood’s residents were already building tents, shacks—any temporary housing they could in order to prove that they were not willing to give up their land. Greenwood’s resilience, Franklin’s lawsuit, and the Reconstruction Committee’s failure to raise enough money to carry out their plans all meant that Franklin’s battle to preserve Greenwood would prove successful and the neighborhood could continue to rebuild. A detailed account of the political battles around Greenwood’s rebuilding appears in Tulsa World journalist Randy Krehbiel’s book, “Tulsa 1921: Reporting A Massacre.”

Many books and articles mistakenly claim that the lawsuit was decided in the Oklahoma State Supreme Court. This is incorrect. After an appeal filed by the city legal department, a three-judge panel of Tulsa County judges (W. B. Williams, Albert G. Hunt and L. B. Biddison) decided in favor of Lockard and ruled that the city sought to deny the property rights of Greenwood’s residents without due process in September 1921. Interestingly, one case that Franklin filed did reach the Supreme Court of Oklahoma. It was a defamation lawsuit that he and fellow attorney Amos T. Hall filed in 1938, against World Publishing Co., the company that owns Tulsa World.

Life after the Massacre

Franklin’s wife and youngest children would not join him in Tulsa until 1925. Mollie Franklin had been teaching in Rentiesville for about twelve years. When she finally settled in Tulsa with her family, she became an active member of her church, social clubs, and established the first daycare for children of working mothers in North Tulsa. She became ill in October 1935, and doctors could not find the source of her illness. She suffered from weariness and low blood pressure and died on November 1, 1936. On her tombstone is inscribed the phrase, “Lifting as we Climb.”

Franklin continued to practice law, working tirelessly to right the wrongs he saw in society. Ever patient and meticulous, he wrote, “Right is slow and tardy, while wrong is aggressive; that’s the only way it can survive. It carries within itself the seed of its own destruction.” He achieved the level of Senior Member of the Oklahoma Bar Association in 1959, and was admitted to practice law at the Supreme Court of the U. S.

Franklin suffered a stroke in 1956, paralyzing the right side of his body. Undeterred, he set about completing his autobiography, working every day by painstakingly typing with the index finger of his left hand. He worked with his son, John Hope, to complete his book’s first draft. However, Franklin did not survive to see his memoir published. He passed away on September 24, 1960. His son and grandson finished editing the book and published it in 1997.

>B. C. Franklin’s Legacy

Tulsa is still learning from B. C. Franklin’s writing and legal work. In 2015, a 10-page letter of his was discovered in a storage facility. It was purchased from a private seller by a group of Tulsans and donated to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture. The letter is dated August 22, 1931, and contains Franklin’s firsthand account of the Greenwood Massacre. Among its contents is an account of the neighborhood’s bombing on the morning of June 1. Franklin writes, “From my office window, I could see planes circling in mid-air. They grew in number and hummed, darted and dipped low. I could hear something like hail falling upon the top of my office building. …The side-walks were literally covered with burning turpentine balls. I knew all too well where they came from, and I knew all too well why every burning building first caught from the top…” The letter goes on to describe families fleeing burning buildings and gunshots. He described witnessing three men shot and killed. He then described being marched at gunpoint to Convention Hall.

Franklin’s detailed eyewitness account written a mere 10 years after the Massacre, together with other survivors’ accounts, articles, and detailed research done in 2017, by aviation historian Thomas Van Hare, have helped settle the historical debate about planes dropping bombs on Greenwood. Thought to have been lost, the court documents for Franklin’s lawsuit against Tulsa, Case No. 15730, Joe Lockard. v. T.D. Evans, Mayor, et al., were recovered from an old microfilm reel by the Tulsa County Administrative Services in 2020. These primary sources shed new light on the Massacre and its aftermath.

Located at 1818 E. Virgin Street, B. C. Franklin Park was created as a project under Tulsa Model Cities in the early 1970s. Over the decades, the park became more and more neglected by the city and was closed in the early 2000s. Community activists in North Tulsa fiercely fought for the city to renovate the park, which was finally re-opened in 2016. The new B. C. Franklin Park in North Tulsa includes a playground, two basketball courts, an outdoor fitness center, and a community garden. Of the park’s rebuilding, District One City Councilor Vanessa Hall-Harper said, “We’ve gone through a real healing process.”

Read Jenkin Lloyd Jones Press’s description of The Victory of Greenwood.

Copyright © 2021 Jenkin Lloyd Jones Press/Carlos Moreno No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher or author. The format of this excerpt has been modified for presentation here.